Original piece: 《火箭:我要飞……………………………得更高!》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 桢公子 & 艾蓝星

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

50 years of defying gravity

*Dedicated to Space Day of China (24 April)

The road to space exploration has never been easy.

Loaded with high expectations from across the nation, ChangZheng-3B (CZ-3B, lit. ‘long march’) made her maiden launch on 15 February 1996, only to veer off course in less than 2 seconds after liftoff.

(photo: Internet Archive)

And just 22 seconds later, the rocket blew up as it hit the ground with its head and turned into dust in the fierce blaze. This was the ninth failure for China’s launch vehicles.

(photo: Internet Archive)

More than 20 years later, and even after 26 successful launches, CZ-3B experienced yet another fall and disintegration on 9 April 2020, due to a malfunction in the third stage engine. This was the 22nd failure* ever recorded throughout the history of Chinese space exploration.

Nevertheless, accompanying these were as many as 334 successful launches.

*Counted as of April 2020, ‘successful’ launches are defined as the delivery of spacecrafts into target orbits.

(photo: 苟秉宸)

Indeed, failures are painful, but one can never reach the heights in science without biting back tears.

“The correct result is derived from a large number of mistakes.“

Qian Xuesen, widely regarded as Father of Chinese Rocketry

And this is exactly how the Chinese made their way to space. The very first artificial satellite that China placed into orbit 50 years ago was a ‘tiny’ product that weighed only 0.178 tonne. Yet in the 50 years that followed, generations after generations of launch vehicles kept defying gravity, sending countless spacecrafts off into the galactic sea again and again.

These include satellite programmes*:

- BeiDou (北斗, lit. ‘Northern Dipper’; navigation satellites)

- FengYun (风云, lit. ‘wind cloud’; weather satellites)

- GaoFen (高分, lit. ‘high resolution’, high-resolution imaging satellites)

- QueQiao (鹊桥, lit. ‘magpie bridge’; relay satellite for the mission on moon’s far side)

- JianBing (尖兵, lit. ‘point man’; military satellites)

- ShiJian (实践, lit. ‘practice’; technology demonstration satellites)

- ChangKong (长空, lit. ‘vast sky’; technology demonstration satellites)

- FengHuo (烽火, lit. ‘beacon’; communications satellites)

- HaiYang (海洋, lit. ‘ocean’; oceanography satellites)

- ShenTong (神通, lit. ‘divine power’ or ‘divine connection’; military communication satellites)

- TanCe (探测, lit. ‘explore’; magnetosphere investigation satellites)

- QianShao (前哨, lit. ‘outpost’; space-based infra-red system defence satellites)

- ZiYuan (资源, lit. ‘resource’; Earth resources satellites)

- XinNuo (鑫诺, SinoSat Co. Ltd; telecommunications satellites)

- TianLian (天链, lit. ‘heaven chain’; tracking and data relay satellites)

- ZhongXing (中星, China Satcom Co. Ltd; communications satellites)

- TianTuo (天拓, lit. ‘expanding the heaven’; experimental satellites)

- TianHui (天绘, lit. ‘drawing the heaven’; survey and mapping satellites)

- LuoJia (珞珈, nickname of Wuhan University, which is located on Luojia Mountain and contributed to the development of this satellite series; luminous remote sensing satellites)

- YunHai (云海, lit. ‘cloud sea’; atmospheric science and oceanography satellites)

As well as space exploration missions*:

- ShenZhou (神舟, lit. ‘divine ark’; crewed spacecraft)

- TianZhou (天舟, lit. ‘heaven ark’; cargo spacecraft)

- Chang’e (嫦娥, Chinese moon goddess; lunar exploration missions)

- TianGong (天宫, lit. ‘heaven palace’; large modular space station)

*Translator’s comment: click here for stories behind some of the China’s spacecraft names

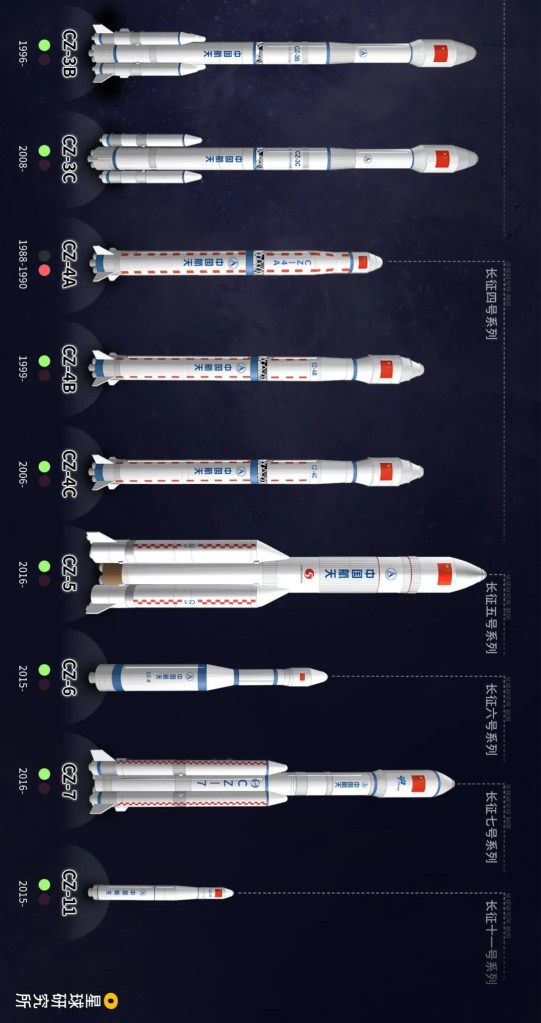

Green: active (现役); red: retired (退役)

Adult male (成年男子) for scale on the left

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

How did we come thus far? And where are we heading from here?

1. The birth of a small-lift launch vehicle

30 January 1970.

China successfully tested DongFeng-4 (DF-4), her first intermediate/long-range ballistic missile.

The takeoff thrust of DF-4 comes from the jet stream produced by combustion, and the propellant used here is a combination of a fuel and an oxidiser. This completely frees the combustion process from the reliance on oxygen, and allows the missile to fly freely even in space where oxygen is not present. Its rocket body is divided into two stages: the first stage at the bottom detaches at high altitudes after accomplishing its task, then the second stage fires and relays the propulsion.

This became the prototype of Chinese launch vehicles.

The white exhaust track on the right is the second-stage rocket continuing the flight

Photo shows successful launching of Hyperbola-1 developed by a Chinese private aerospace enterprise

(photo: 余明)

But for a satellite to orbit around the Earth, it needs an altitude higher than 180 kilometres, and that requires an orbit entry speed reaching almost 7.9 km/s, otherwise the satellite will end up falling back to the atmosphere due to gravity and atmospheric friction.

This is the 7.9 km/s mentioned above

(diagram: 陈思琦&陈随, Institute for Planets)

Unfortunately, both the required speed and altitude are utterly beyond of the reach of DF-4, so engineers added yet another stage to the vehicle to make a three-stage rocket. At the rocket nose, they replaced the missile warhead with a satellite, and shielded it from the impact of high-speed airflow with a fairing.

Payload fairings on rockets are held together by an explosive bolt which, when fired, separates and releases the fairings

(photo: 王若维)

The first and second stages are connected by metal rods, where the point of contact adopts a hollowed-out design to facilitate efficient discharge of spraying flame during the firing of the second stage.

Inclined metal rods connect the two stages with a hollowed-out structure

Fragments peeling off from the rocket are remainings of the foam insulation layer

(photo: 韩超)

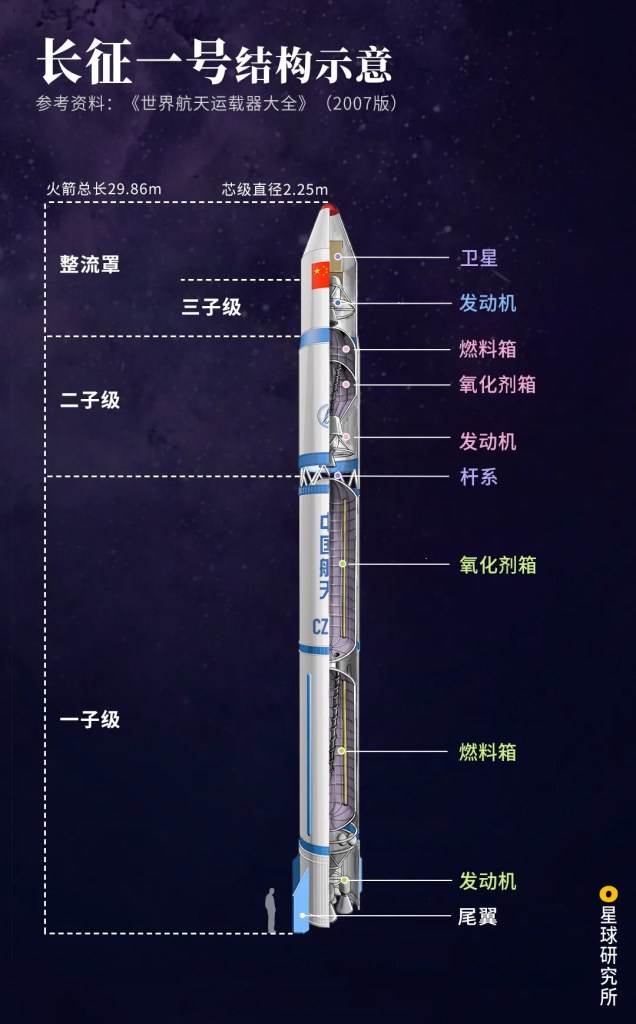

After a series of optimisation, the DF-4 was transformed into ChangZheng-1 (CZ-1), China’s first launch vehicle.

Rocket total length (火箭总长): 29.86 m; payload diameter (芯级直径): 2.25 m

Left: payload fairing (整流罩), first stage (一子级), second stage (二子级), third stage (三子级)

Right: satellite (卫星), engine (发动机), fuel tank (燃料箱), oxidiser tank (氧化剂箱), rod system (杆系), fins (尾翼)

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

With a diameter of 2.25 metres and a height of approximately 30 metres, it can deliver payloads of not more than 0.3 tonne to the Low Earth Orbit at about 440 kilometres above ground, including Dongfanghong-1, China’s first satellite. This made China the fifth country, after the Soviet Union, United States, France and Japan, to be able to independently send artificial satellites into space, and marked the beginning of a new era of Low Orbit satellites for the Chinese aerospace field.

(photo: Brücke-Osteuropa)

However, a load of 0.3 tonne can hardly fulfil the requirements of a satellite. The launch vehicle needed an upgrade.

For the propellant, engineers switched to a brand new combination of fuel and oxidiser, namely unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine and dinitrogen tetraoxide, which are both in liquid form at room temperature. These new chemicals have a higher propulsion efficiency*, and since they combust instantly upon contact, ignition is simple and maintenance is convenient.

*Propulsion efficiency here refers to the specific thrust, which is defined as the thrust generated per unit propellant per unit combustion time, same below.

(photo: 阿毛)

Changes were made to the hardware too. The diameter was increased to 3.35 metres to match the size limit of rail transportation. Thanks to the larger diameter and stronger propellant, the payload can now enter orbit even with only a two-stage launch vehicle.

(photo: Donald)

One of the upgraded rockets was named FengBao-1. With its help, China was for the first time able to deliver satellites heavier than 1 tonne into orbit, as well as to ‘launch three satellites with one rocket (一箭三星)’.

(photo: 苟秉宸)

Also in this upgrade batch is the CZ-2, which has a Low Earth Orbit* load of 1.8 tonnes. It successfully launched the first recoverable satellite, which was a major step forward for manned space exploration in China.

*Low Earth Orbit here refers to orbits with altitudes between 200-400 kilometres, same below unless otherwise stated.

(photo: VCG)

But up to this point, the Low Earth Orbit load of Chinese launch vehicles had yet to exceed 2 tonnes, and thus were still categorised as small-lift launch vehicles. The dream of having bigger satellites and exploring deeper star sky, or the glorious missions to send astronauts to space and build a space station, will have to count on the next-generation rockets.

2. The mission of medium-lift launch vehicles

Medium-lift launch vehicles have a Low Earth Orbit load between 2 to 20 tonnes.

After making improvements based on the foundations of the CZ-2, the CZ-2C and CZ-2D are almost 10 metres taller than their mother rocket and can carry much more fuel with them. Built with better materials and equipped with more powerful engines, the Low Earth Orbit load now goes up to about 4 tonnes. That officially places them into the medium-lift launch vehicle family and among the major forces for launching recoverable satellites.

CZ-2D also incorporated technologies used in CZ-4

(photo: 曾诚宇)

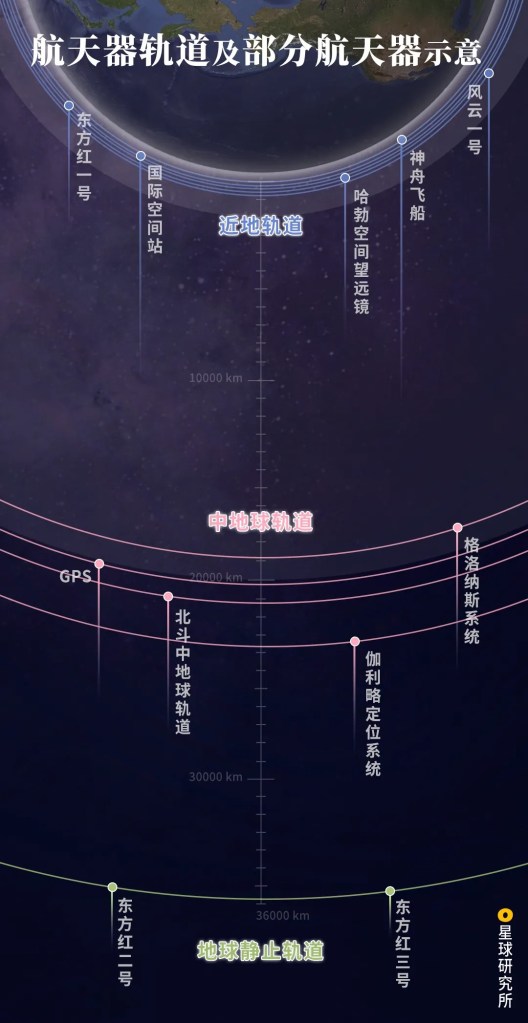

This type of satellites usually orbits at an altitude of about several hundred kilometres. On the contrary, the orbit height of weather satellites and navigation satellites can reach up to 1,000 and 20,000 kilometres respectively.

One orbit has a plane that coincides with the equatorial plane. It is even further out at 36,000 kilometres, where satellites stay stationary above the same point on the ground. This is known as the geostationary orbit. Under ideal conditions, only three satellites are needed in this orbit to provide global coverage.

Low Earth Orbit (近地轨道): Dongfanghong-1 (东方红一号), International Space Station (国际空间站), Hubble Space Telescope (哈勃空间望远镜), Shenzhou spacecraft (神舟飞船), FengYun-1 (风云一号)

Medium Earth Orbit (中地球轨道): GPS, BeiDou Medium Earth Orbit (北斗中地球轨道), Galileo Navigation System (伽利略定位系统), GLONASS (格洛纳斯系统)

Geostatoinary Orbit (地球静止轨道): Dongfanghong-2 (东方红二号), Dongfanghong-3 (东方红三号)

(diagram: 陈思琦&陈随, Institute for Planets)

But to arrive at the Geostationary Orbit is nothing like a mere walk in the park. To enter this orbit at a specified location, satellites have to do a multi-level jump, where they first enter a transitional orbit* with a speed of 10 km/s and then adjust course with high precision before sailing towards the target location. This means that we need a rocket that can fly farther, higher and with a better aim.

*Also known as the Geostationary Transfer Orbit.

Geostationary Orbit (地球静止轨道): altitude 高度 = 35786 km, overlaps with equatorial plane (赤道平面)

Geostationary Transfer Orbit (地球同步转移轨道): perigee height (近地点高度) = 600 km, apogee height (远地点高度) = 35786 km, orbit inclination (轨道倾角) = 19°

(diagram: 陈思琦&陈随, Institute for Planets)

The first thing engineers went for was again additional vertical staging, but they were soon faced with a dilemma: either take a risky approach and develop a new system, or go for a higher chance of success building on conventional technologies.

In the risky approach, engineers would use the CZ-2C model as a reference, and replace standard ambient temperature fuels with a cryogenic propellant (liquid hydrogen + liquid oxygen) in the third stage of the rocket. While this new propellant further enhances propulsion efficiency, a cryogenic engine is a real challenge to develop. Moreover, the liquid hydrogen is highly inflammable and explosive, and has to be stored at temperatures below -253°C. Taking this approach would mean that engineers have to figure out everything, from cryogenic engine technology to fuel storage, transportation and refilling, completely from scratch.

Photo shows disassembled fuel tanks

(photo: 宿东)

In the second and less risky approach, engineers would build on the foundations of the FengBao-1 model and use conventional ambient temperature propellant in the third stage, which was then a very mature technology.

A technological breakthrough or a risk-free mission?

The whole team of engineers went into an intense debate which seemed endless, until finally when Ren Xinmin, chief engineer of China’s communications satellites, stood out and said,

If China were to become a major aerospace power by the end of the century and be rid of the backward image, she must aim at the pinnacle of contemporary rocket engine technologies……

Aerospace industry is in itself a great risk, there is no point staying in this field if one is afraid of failures and risks!

— Ren Xinmin 《天穹神箭》(“Divine Arrow through the Heavens“), by China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology

These determined and sound words made an enormous impact and essentially led the way for modern Chinese rocket technology thereafter. Engineers took none other than the first risky approach, and finally developed the third stage engine (liquid hydrogen + liquid oxygen) in what would become the mainstay launch vehicle for geostationary orbit satellites in the following decade or so — CZ-3.

Payload fairing (整流罩), first stage (一子级), second stage (二子级), third stage (三子级)

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

The propellant tank in the third stage of CZ-3 is equipped with anti-freezing, anti-seepage, moisture-proof and heat-proof properties, whereas the engine there is capable of secondary ignition which allows the satellite to accelerate again to enter the transitional orbit.

And the CZ-3A, born after another round of upgrading, was the first to deliver Chinese satellites to the Lunar Transfer Orbit, which is the only way to the Moon. This marked the beginning of Chang’e era of the Chinese space programme.

(photo: 雨水)

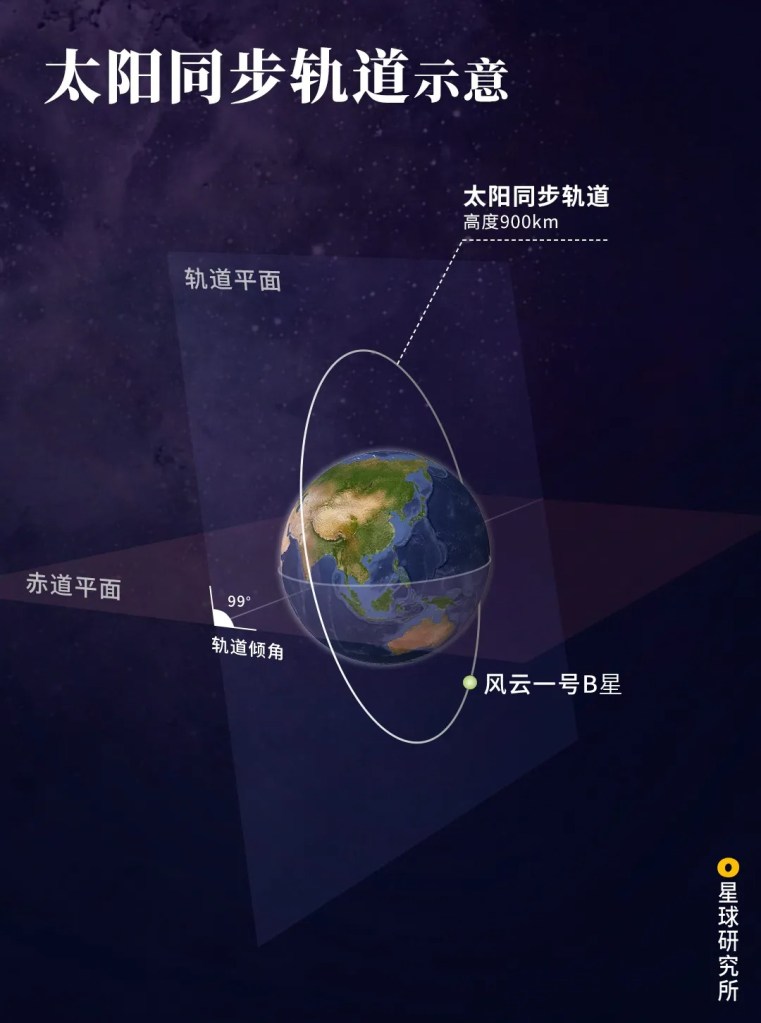

But the other less risky approach was never forgotten and had made substantial progress simultaneously to create the CZ-4 series (CZ-4A, CZ-4B, CZ-4C). They are primarily responsible for launching Sun-synchronous Orbit satellites.

(photo: 史悦)

This is yet another unusual orbit, where the orbit plane rotates around the Earth’s axis in a process known as precession which synchronises with Earth’s revolution around the Sun, such that the surface illumination conditions on Earth is always maintained the same whenever the satellite is overhead. It is most suitable for weather or ground observation.

But the inclination of this type of orbit is usually larger than 90°. This means that launch vehicles have to provide large amount of thrust for course adjustment of the satellite.

Orbital plane (轨道平面), equatorial plane (赤道平面), orbital inclination (轨道倾角) = 99°

(diagram: 陈思琦&陈随, Institute for Planets)

This was why the launching of FengYun-1 weather satellite on CZ-4A on 7 September 1988 received so much attention both within and beyond China. FengYun-1 officially declared the end of China’s dependence on foreign weather satellite data when it successfully entered the Sun-synchronous Orbit, which has an inclination of 99° and at 900 kilometres above Earth.

(photo: 阿毛)

At this point, the Low Earth Orbit load of China’s medium-lift launch vehicles had already reached 6 tonnes.

But to realise the dream of manned space exploration, the load has to be at least about 8 tonnes, yet the lifting thrust of single-core rockets* has pretty much reached their upper limit. What next?

*Single-core rockets are those containing only one column of multistage engines, much like a divine pillar reaching for the sky (一柱擎天)

(photo: VCG)

An easy answer to that is horizontal bundling.

Based on the CZ-2C model, engineers first elongated the rocket core vertically with additional staging to increase propellant reserves to appropriate levels, then bundled 4 smaller rockets to it on the side. Each of these additional modules, known as boosters, is 15.3 metres tall and 2.25 metres wide. It is always a magnificent sight to behold during takeoff when 8 engines (4 core and 4 booster) are ignited at the same time.

(photo: 史悦)

This revised model became known as CZ-2E, the first strap-on rocket to come on stage in China. Its takeoff thrust is almost twice that of CZ-2C, and has a Low Earth Orbit load of approximately 9.5 tonnes. Impressively, it took only 18 months from development to the first launch.

Boosters ()

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

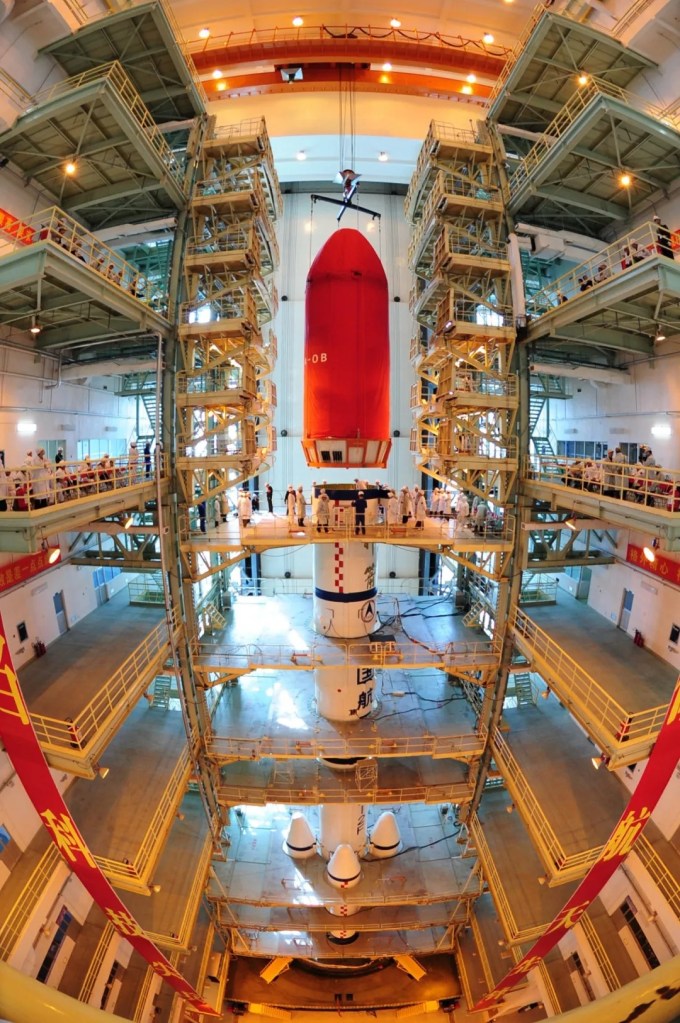

But it was the famous CZ-2F which truly turned the dream of manned space exploration into reality.

It was assembled, tested and transported vertically

(photo: 孙海英)

Its appearance is very different from that of CZ-2E, owing to a pointy ‘hat’ installed at the top of the payload fairing which is know as the escape tower.

Left: upper payload fairing (上部整流罩), escape tower (逃逸塔)

Right: propulsion cabin (推进舱), escape separation surface (逃逸分离面), return cabin (返回舱), orbital module (轨道舱), escape tower separation surface (逃逸塔分离面)

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

This is a safety device which can be promptly ignited upon any unexpected events that may occur (between the 15 minutes prior to takeoff and 120 seconds after) and be separated together with orbital module and return cabin from the rocket core, thereby bringing the astronauts out of any danger. It is also referred to as the ‘tower of life’.

It will be launching the manned ShenZhou-7

(photo: VCG)

In addition to emergency systems including the escape tower, there are also a backup of the main control system as well as an automatic fault detection system installed on the CZ-2F. All these together raise its design reliability score to 0.97 from CZ-2E’s 0.91 (1.00 being the highest).

And it indeed kept its promise to send Yang Liwei, China’s first astronaut, safely into space on 15 October 2003, making China the third country in the world to launch a manned spacecraft.

(photo: 央视网)

CZ-2F continued to achieve throughout its 21 years of service. From ShenZhou-1 to 11, and TianGong-1 to 2, it had launched 5 unmanned missions, 6 manned spacecrafts and 2 space laboratories in total, with a staggering success rate of 100%. It surely is worthy of the title ‘divine arrow‘.

A portion of the ‘divine arrow (神箭)’ markings can be seen on the rocket

(photo: 宿东)

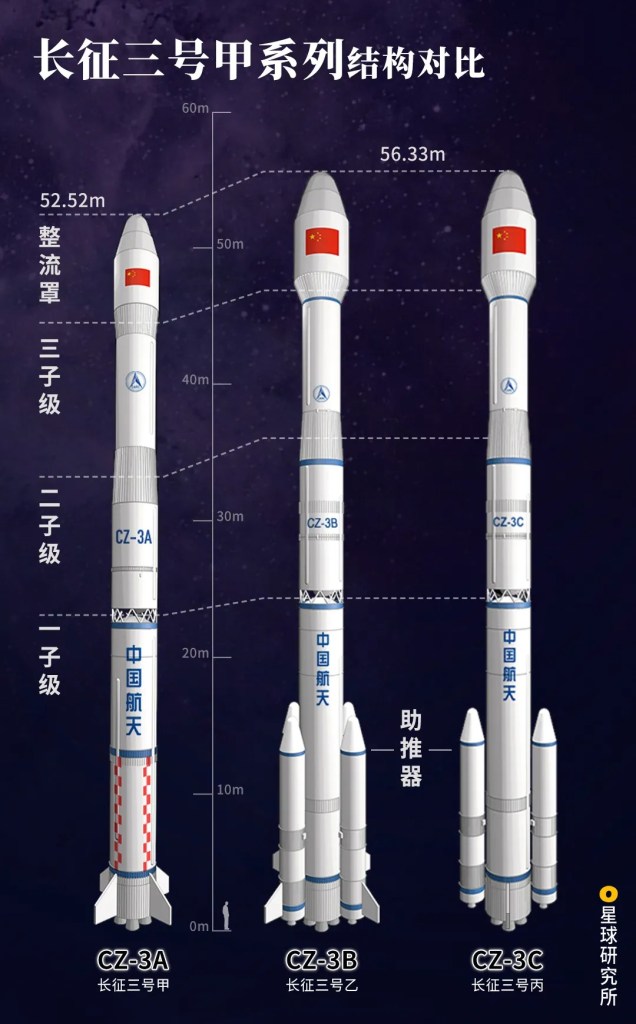

All the members in the CZ-2 family are two-stage rockets. To make a three-stage strap-on rocket, one simply needs to extend the core of CZ-3A and bundle it up with boosters. This is how CZ-3B and CZ-3C were born.

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

CZ-3C, in particular, has been the top-notch launch vehicle in China for the past 20 years or so, and has pretty much single-handedly undertaken most if not all medium-to-high orbit launchings. As a three-stage strap-on rocket with 4 boosters, it was the first to have a Low Earth Orbit load that goes beyond the 10-tonne mark and reaching almost 11.5 tonnes.

(photo: 史悦)

After launching the Chang’e-3 and Chang’e-4 missions, it was branded with the name ‘heaven’s ladder to the Moon‘.

(photo: 蒋涛)

But as the saying goes,

“When China’s launch vehicles wake up from the euphoria of consecutive successes, they will be faced with 4 formidable opponents.”

Quoted from《神箭凌霄:长征系列火箭的发展历程》

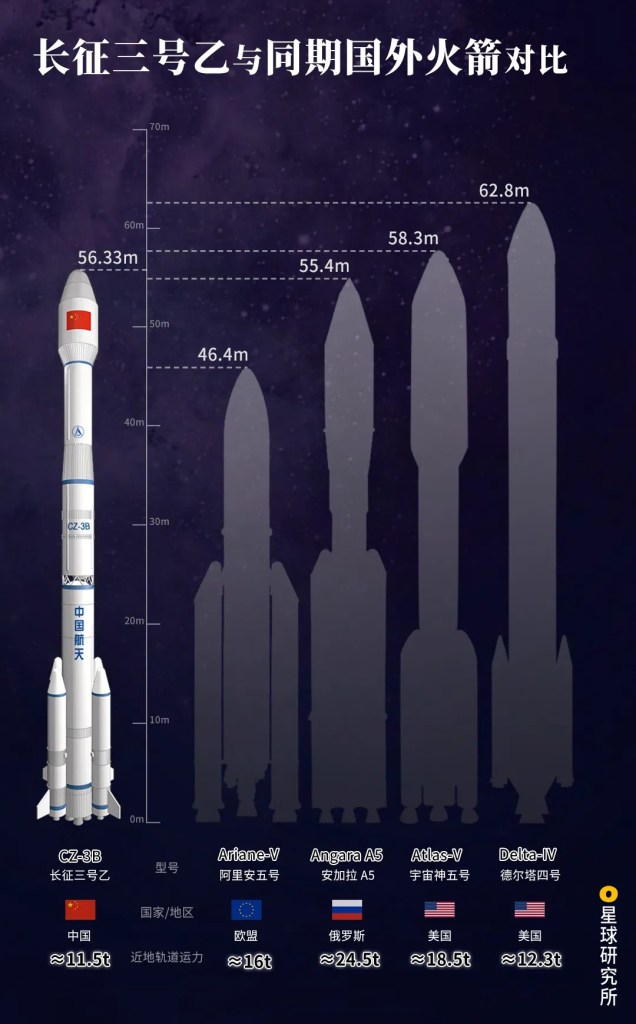

At the turn of the 21st century, commercial large rockets developed by the United States, Europe and Russia made their appearance one after and other. Some not only have a load twice as that of CZ-3B, but are also more environmentally friendly and allow more rapid deployment with a lower cost. In comparison, China’s launch vehicles were lacking behind in virtually all aspects.

Low Earth Orbit load (近地轨道运力)

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

A comprehensive upgrade was urgently needed.

Firstly, the unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine and dinitrogen tetraoxide fuel combination, which had been in use for almost 40 years, was gradually abandoned and replaced by the kerosene and liquid oxygen team. Not only does this new fuel combination cost vastly less, the carbon dioxide and water produced by its combustion is no longer toxic and much less polluting. Secondly, engines were also upgraded with 15% higher propulsion efficiency*. And lastly, the new boosters are now almost 27 metres tall, which is almost two times the height of any other boosters developed to date.

This rocket is now called the CZ-7.

*Propulsion efficiency here refers to sea level specific thrust.

(photo: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

It has a Low Earth Orbit load of approximately 14 tonnes, and hence is capable of launching the 13-tonne TianZhou-1 cargo spacecraft. As the crucial player in the upcoming Chinese space station era, it will slowly take over the tasks currently performed by CZ-2, CZ-3 and CZ-4 series and be responsible for about 80% of all launching missions to come.

The design reliability score of CZ-7 is 0.98, which is even higher than that of CZ-2F

(photo: 宿东)

With that, the introduction of China’s medium-lift launch vehicles shall come to an end. To launch something with a Low Earth Orbit load of more than 20 tonnes, we have to look to the contenders in the next generation.

3. The great arena of heavy-lift launch vehicles

The Wenchang Satellite Launch Centre in Hainan was completed in October 2014.

With a lower latitude and being closer to the equator, the launch centre can fully utilise the Earth’s rotational force to enhance launching efficiency of rockets. Additionally, it can reduce course adjustment and flight distance when launching Geostationary Orbit satellites. Compared to the Jiuquan launch site, the quality of orbit entry for satellites launched here is 16.3% to 18.5% higher*.

*Data from《天穹神箭》(“Divine Arrow through the Heavens“) by China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology.

Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre (酒泉卫星发射中心), Alxa, Inner Mongolia (completed in 1960)

Taiyuan Satellite Launch Centre (太原卫星发射中心), Xinzhou, Shanxi (completed in 1968)

Xichang Satellite Launch Centre (西昌卫星发射中心), Liangshan, Sichuan (completed in 1982)

Wenchang Satellite Launch Centre (文昌卫星发射中心), Wenchang, Hainan (completed in 2014)

(photo: 陈思琦&陈随, Institute for Planets)

Moreover, it is the first coastal launch site in China, with nothing but the vast sea within thousands of kilometres to the southeast. This ensues the safety from falling debris.

(photo: 陈肖)

But more importantly, rocket parts can now be shipped without the 3.35-metre diameter limit set by railways.

(photo: 宿东)

With all these settled, China’s first heavy-lift launch vehicle, CZ-5, finally made its debut appearance.

Although being a two-stage rocket, it has an unusual height of about 57 metres, which is equivalent to a 20-storey building and on par with other three-stage rockets that are currently in service. Horizontally, the diameter of the core is enlarged from 3.35 metres to 5 metres, while that of the 4 boosters from 2.25 metres to 3.35 metres. No wonder this colossal monster is given the name ‘chubby-5 (胖五)‘.

CZ-5: rocket height (火箭总长) = 56,97 m; core diameter (芯级直径) = 5 m, booster diameter (助推器直径) = 3.35 m

First stage (一子级) & second stage (二子级): engine (发动机), kerosene tank (煤油箱), liquid hydrogen tank (液氢箱), liquid oxygen tank (液氧箱)

Payload fairing (整流罩): satellite (卫星)

(diagram: 陈随, Institute for Planets)

In contrast to CZ-7, the core of CZ-5 has completely switched to a cryogenic propellant using a combination of liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen paired with a completely new engine design, and each booster has 8 engines which is twice as many as in CZ-7. During takeoff, a total of 10 engines will be ignited simultaneously which boosts the takeoff thrust by a further 50%. All these together contribute to the 25-tonne Low Earth Orbit load.

The exhaust flame appears blue due to the cryogenic propellant consisting of low-temperature hydrogen and oxygen used in the two-stage core; CZ-5 is also known as the ‘ice rocket’ because of this

(photo: 陈肖)

CZ-5 is to date China’s most powerful launch vehicle with the largest mass and widest diameter, scoring a second runner up in the world ranking of active rockets right after United States’ Falcon Heavy and Delta IV.

(photo: 陈肖)

On 3 November 2016, the first CZ-5 made a successful maiden flight under all spotlights. This was also the first time for a launch vehicle to directly send a satellite into the Geostationary Orbit. But this is just the beginning of CZ-5’s adventures that will continue for the next three decades or more, as it go on to witness all the historical moments including exploration on the Moon and Mars, as well as other deep space missions including the solar orbiting space telescope project.

(photo: CNAurora)

Nonetheless, the dream of super rockets does not just end here.

Looking around the world, the most powerful rocket ever built in terms of launching ability is the Saturn V developed by the US, which has a Low Earth Orbit load of 140 tonnes. It has been driving the Apollo project since 1967, a breathtaking record which is yet to be broken.

It was first launched with Apollo 4 on 9 November 1967

(photo: NASA)

After decades of catching up, China’s own heavy-lift launching vehicles are finally expected to come on stage between 2028 and 2030. One of them will be the CZ-9, which has a total height exceeding 100 metres and core diameter almost hitting 10 metres (twice that of chubby-5). Its Low Earth Orbit load will go beyond 100 tonnes, which is absolutely staggering even just thinking about it. It will take on much more challenging missions such as manned landing on the Moon, Mars sample return, or even exoplanet exploration in the solar system.

4. The great voyage

China’s launch vehicle family has been growing non-stop over the past 50 years. While the team of large rockets is expanding by the day, smaller ones are also blooming like never before.

For instance, CZ-6 is capable of quick launching from the simplest launcher, and has once achieved ‘launching 20 satellites with one rocket (一箭20星)’.

(photo: 李岗)

CZ-11, with a height of not more than 20 metres and a diameter of only 2 metres, can be launched directly on offshore platforms.

(photo: VCG)

KuaiZhou-1, an even smaller rocket with a diameter of only 1.4 metres, allows rapid response and flexible deployment. The shortest preparation time in between two launches is 6 hours.

(photo: VCG)

Besides, numerous private launch vehicles are becoming technologically mature, and reusable rockets are also being developed.

(photo: 陈肖)

Today, led by the CZ series, China’s launch vehicles are becoming more and more comprehensive in terms of launching ability and orbit coverage. This makes journeys towards the Moon, Mars or space further out possible.

It is true that in every mission launch vehicles are only involved in the beginning of the journey, but never get to be part of the ending. A successful separation from the payload would mean their purpose fulfilled and hence a time to retire from the stage.

They either vanish in the atmosphere…

(photo: 陈肖)

…or fall into some wilderness or the vast sea…

(photo: 在远方的阿伦)

…leaving behind the satellite or spacecraft which continues with the galactic journey.

As Li Bai, a renowned poet in the Tang Dynasty, had put it:

Be gone after accomplishing the quest, leaving behind nothing nor a name

事了拂衣去,深藏身与名

Li Bai, 《侠客行》(Ode to Gallantry)

Such is the inevitable destiny of launch vehicles. In the same way, generations of scientists have left behind their proud work for their successors, who continue the hike to new heights in science.

There will be a time when the BeiDou constellation is fully configured and the ShenZhou roaming freely across the sky; when Chang’e is flying to the Moon and Mars landed on; and when TianZhou is shuttling between Earth and Space and TianGong majestically completed.

This, will be the most glorious moment for our grand road to space exploration.

(photo: 陈肖)

Production Team

Text: 桢公子,艾蓝星

Photos: 任炳旭

Design: 陈随

Maps: 陈思琦

Review: 张照,云舞空城

Expert review

Dr. Zhang Borong, Chinese Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to photographer 阿毛 for the immense support provided during the production of this piece.

References

[1]陈闽慷, 茹家欣. 神箭凌霄:长征系列火箭的发展历程[M]. 上海科技教育出版社, 2007.

[2]中国运载火箭技术研究院. 天穹神箭: 长征火箭开辟通天之路[M]. 中国宇航出版社, 2008.

[3]李成智. 中国航天技术发展史稿[M]. 辽宁教育出版社, 2006.

[4]《世界航天运载器大全》编委会. 世界航天运载器大全[M]. 中国宇航出版社, 1996.

[5]冉隆燧. 航天工程设计实践[M]. 中国宇航出版社, 2013.

[6]刘家騑, 李晓敏, 郭桂萍. 航天技术概论[M]. 北京航空航天大学出版社, 2014.

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光

kk, great job

LikeLike