Original piece: 《…况且况且况且况且…》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 桢公子

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

China’s Bones of Steel

Dedicated to all those who are on their journey home

Translator’s comment:

The original title in Chinese is pronounced as ‘…kuangqie-kuangqie-kuangqie-kuangqie…’, which is an onomatopoeia for the running wheels of Chinese trains from the previous generation. It is a characteristic rumble that resonates with the bittersweet memories in all those who have witnessed the rise and fall of the preceding railroad dynasty in China.

The Spring Festival travel season in 2019 started on the 21 January.

This day marked the beginning of another year of the great migration in China.

In the following 40 days, buses, trains, ferries and air flights across the country would accommodate a staggering passenger volume of up to 2.99 billion, which is equivalent to transporting 40% of the population on Earth within a month or so. The scale of this Chinese migration is unrivalled in the whole world.

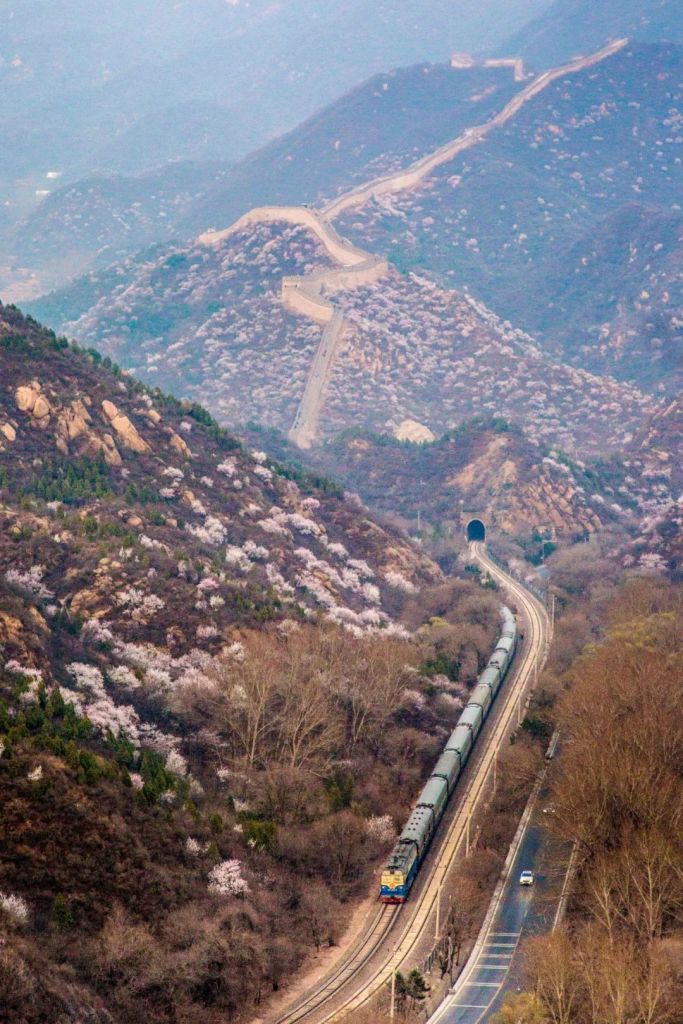

(photo: 毕加思索)

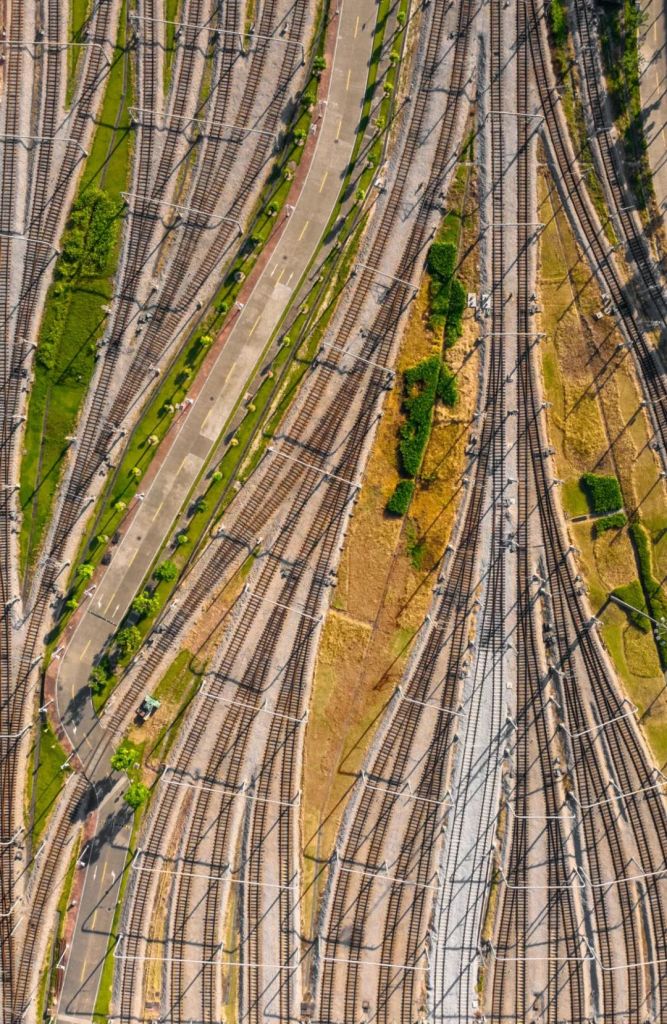

An indispensable component of public transport in China is the railroad system. Stretching from inland to the coast, venturing deserts and jungles, and shuttling between cities and rural villages, it forms an elaborate network of steel skeleton that reaches almost everywhere in the country. Throughout the Spring Festival travel season, there would be approximately 4800 pairs of trains speeding back and forth, tirelessly escorting waves of passengers to their destinations thousands of miles away.

(photo: 毕加思索)

How did China grow her bones of steel as it is today?

This is not something that can be explained in a few words. To get a glimpse of China’s struggles in railroad development, one has to go all the way back in time. It all started slightly more than 140 years ago, when the Chinese railroad was still a blank canvas…

1. The First Network

In 1878, when the total railroad mileage around the world had already exceeded 200,000 kilometres, the Qing government decided to dismantle the Woosong Railway which was surreptitiously built by the British. China’s railroad mileage fell right back to zero.

But no one can refuse the unstoppable course of time, not even the Great Qing.

Because of the increasing demand for coal, the Qing government had no choice but to pay for the construction of the 9.3 kilometres long Kaiping Colliery Tramway, just 4 years after the dismantling of Woosong Railway.

This first railway in China represents the shabby starting point for the country’s railroad development.

(photo: 樱花下的新幹线)

After the utter defeat of the Qing government in the First Sino-Japanese War, Western powers wasted no time to grab hold of the rich resources and military benefits in China by building numerous railroads on the Chinese territories through cession and loans.

The Chinese Eastern Railway built by the Russian Empire in 1903 stretched from Manzhouli in the west to Suifenhe in the east. With branches reaching Harbin, Shenyang and Dalian, the entire railway spanned more than 2400 kilometres.

(photo: 李睿)

These two railways traverse the northeast plains perpendicularly like a ‘T’.

(photo: 房星州)

The old Kaiping Colliery Tramway was also constantly expanding. Starting off with merely 9.3 kilometres, it eventually extended beyond 1000 kilometres in total, connecting the Zhengyangmen (or ‘gate of the zenith sun’) in Beijing and Shenyang, which are separated by the Shanhai Pass. It became part of the old Beijing-Harbin Railway.

The new route no longer runs through Tianjin and the Kaiping Colliery Tramway, but instead goes past Tongzhou, Lanwopu and Luan County before finally arriving at Qinhuangdao; this section is also know as the Beijing-Qinhuangdao Railway

(photo: 李睿)

Building on the framework of the Chinese Eastern Railway and old Beijing-Harbin Railway, the railroad network spread out gradually in the northeast. By the late Republic era, this network accounted for 40% of the total mileage in China. It not only prepared the region for the upcoming rapid industrialisation, but also laid the important groundwork for the Jing-Jin-Ji-Northeast Corridor today.

Manzhouli (满洲里), Qiqihar (齐齐哈尔), Harbin (哈尔滨), Suifenhe (绥芬河), Changchun (长春), Siping (四平), Tongliao (通辽), Shenyang (沈阳), Dalian (大连), Qinhuangdao (秦皇岛), Tangshan (唐山), Beijing (北京), Tianjin (天津), Ulanqab (乌兰察布)

Taiyuan (太原), Shijiazhuang (石家庄), Jinan (济南), Zhengzhou (郑州)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Southern cities like Shanghai, Wuhan and Guangzhou, which are all nurtured by rivers and embraced by the sea. Before the capital city was relocated to Nanjing by the Republic government, they were already prospering with their established shipping and trading industries. In contrast to the rising stars in the south, key neighbours of Beijing, the capital city then, were dully stuck in the far north. Thus, railroads were assigned the glorious mission to link up all the major cities across the country.

This prompted the completion of the Shanghai-Nanjing Railway and Tianjin-Pukou Railway in East China, which connect Nanjing with Shanghai and Tianjin respectively.

(photo: 姜南)

And in Central and South China, the Beijing-Hankou Railway, as well as the Yuehan Railway running between Guangzhou and Wuchang, formed the preliminary railroad system that bridges the north and the south.

(photo: 石耀臣)

The Yuehan Railway was completed in 1936 amid the raging wars and extreme shortages of resources. But in order to maintain the logistic support and development behind the frontline, the construction had to go on despite the displacement of large crowds of civilians.

Also completed around the same period was the Hunan-Guangxi Railway, which branched out next to the Yuenhan Railway to connect the two provinces in the south.

(photo: 蓝染天际)

However, there was one issue with the two railways connecting the north and south — the Yangtze River, which mercilessly cuts both of them into half. With the track separated by the natural moat, trains had to rely on ferries to reach the other side of the water.

This ferry operates on the Xinyi-Changxing Railway

(photo: 杨诚)

It was not until after the completion of the Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge and Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, when the famous Beijing-Guangzhou Railway and Beijing-Shanghai Railway could finally run uninterrupted across the grand river.

(photo: 徐晨宇)

It was several decades later when the third railway connecting the north and south was completed. Shuttling between Beijing and Kowloon, Hong Kong, this railway was built almost in perfect parallel with the Beijing-Guangzhou Railway, but lacks all the bustle and hustle throughout its journey, as it passes through only one provincial capital city (Nanchang). This is the Beijing-Kowloon Railway.

(photo: 王璐)

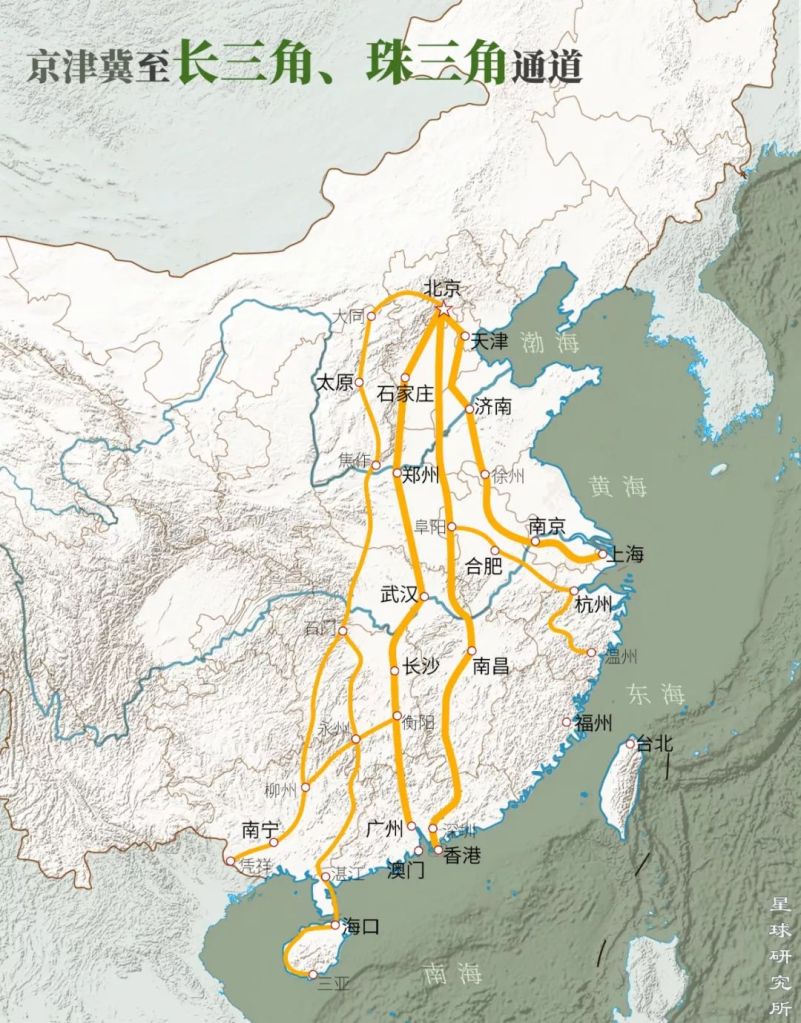

Together, the Beijing-Shanghai, Beijing-Guangzhou and Beijing-Kowloon Railways have become the major backbone for transportation between the Jing-Jin-Ji Metropolitan Region and the Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas.

Beijing (北京), Tianjin (天津), Jinan (济南), Xuzhou (徐州), Nanjing (南京), Shanghai (上海)

Fuyang (阜阳), Hefei (合肥), Hangzhou (杭州), Wenzhou (温州), Nanchang (南昌), Shenzhen (深圳), Hong Kong (香港)

Shijiazhuang (石家庄), Zhengzhou (郑州), Wuhan (武汉), Changsha (长沙), Hengyang (衡阳), Guangzhou (广州), Macau (澳门)

Datong (大同), Taiyuan (太原), Jiaozuo (焦作), Shimen (石门), Yongzhou (永州), Liuzhou (柳州), Nanning (南宁), Pingxiang (凭祥), Zhanjiang (湛江), Haikou (海口), Sanya (三亚)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Wars and political turmoil that lasted for almost a century finally died down with the establishment of New China. In a completely devastated and dirt poor country, rebuilding the economy and consolidating national defence were the top priorities. Hence, even the extreme shortage of capital and lack of technology did not stop Chinese railroads from stretching out into barren deserts and precipitous mountains in the most remote territories.

(photo: 张一飞)

The Chengdu-Chongqing Railway which started operating in 1952 was the first train that ran in Sichuan, and was the first railway constructed by the new Chinese government. In the coming decades, Chinese railroad went on numerous ‘great expeditions’ in the southwest. Gradually, key cities in the southwest, including Chengdu, Chongqing, Guiyang and Kunming, were linked up one by one by the Chengdu-Chongqing, Chengdu-Kunming, Sichuan-Guizhou and Guiyang-Kunming railways.

(photo: 武嘉旭)

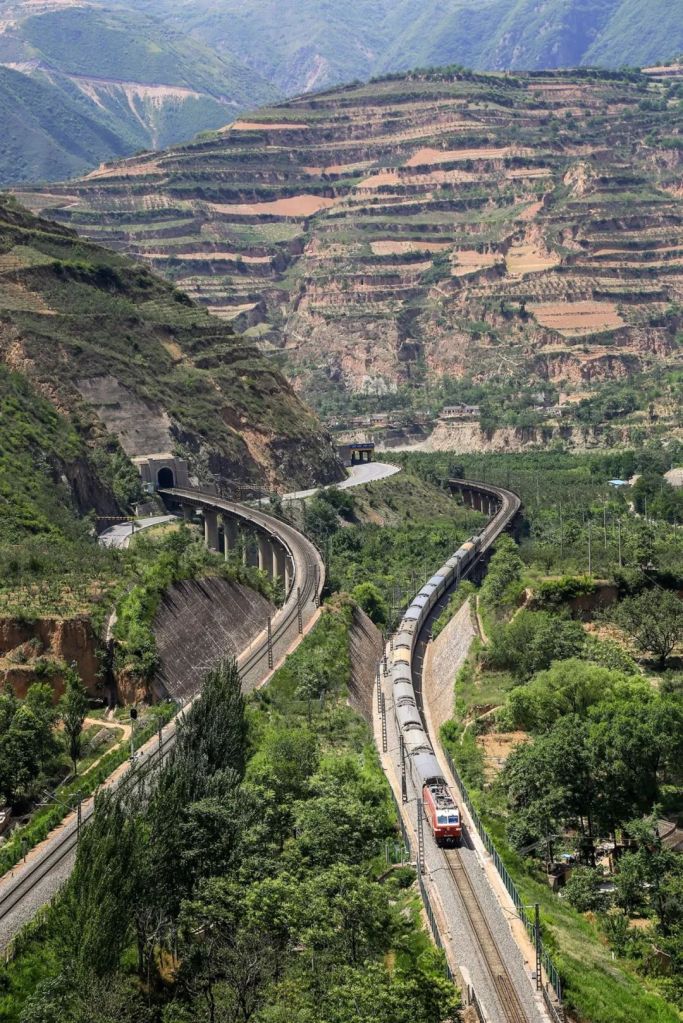

Shortly after, the Xi’an-Ankang Railway squeezed through the Qinling Mountains, whereas Neijiang-Kunming Railway climbed an impressive height of 1300 metres.

(photo: 周德久)

And the famous Chengdu-Kunming Railway travels through one of the most complex landforms and steep terrains in China, which is referred to as a ‘geology museum’ owing to the frequent occurrence of earthquakes, landslides and mudslides.

A stone slope protection was built on the almost vertical cliff during the construction of Chengdu-Kunming Railway to prevent landslides

(photo: 武嘉旭)

There was a heated debate regarding the route during the planning phase of the Chengdu-Kunming Railway. Soviet experts strongly recommended the Central Line plan, which was the shortest and easiest to construct. But the Chinese government was more focused on reaching coal and steelworks plants, as well as opening up areas where most ethnic minorities live.

After careful consideration, the Chinese government decided to build the West Line, which was the longest and would travel across the most dangerous landforms. Nonetheless, the Chinese eventually delivered the hardest route that was ‘absolutely unsuitable for railway construction’ by building 991 bridges and 427 tunnels in the mountains.

(photo: 张一飞)

There is one more mountain railway running in the southeast. Once the only railway connecting Fujian with the rest of the country, the Yingtan-Xiamen Railway tunnels through the Wuyi Mountain and aims for the Xiamen Strait.

(photo: 张雨河)

In the northwest, a railway crosses the Yellow River three times and traverses the Tenggar Desert. Travelling between Baotou and Lanzhou, this Baotou-Lanzhou Railway was the first desert railway in China.

(photo: 徐晨宇)

To reach Beijing, one can travel east on the Baotou-Lanzhou Railway and change to the Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway. For more than 100 years, the latter has remained a household name because of the legendary achievements of Zhan Tianyou, chief engineer of the railway — the first in China to be completed without any foreign assistance.

(photo: 张一飞)

The alternative route for Beijing-Zhangjiakou Railway, which was reluctantly scraped by Zhan Tiaoyou because of production cost and time constraint, was finally completed half a century later. This second passage between Beijing and Zhangjiakou is today known as the Fengtai-Shacheng Railway.

(photo: 杨诚)

To the west of Baotou-Lanzhou Railway, there is the Linhe-Hami Railway which brushes the China-Mongolia border and crosses Gobi Desert, and the Southern Xinjiang Railway which runs right through the Tianshan (literally ‘Mountain of the Heavens’) at an elevation of 3000 kilometres and connects Turpan and Kashgar.

(photo: 周德久)

As well as the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, which treks the Kunlun Mountains, Tanggula Mountains and the permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau.

The railway is the highest and longest highland railway in the world

(photo: 张一飞)

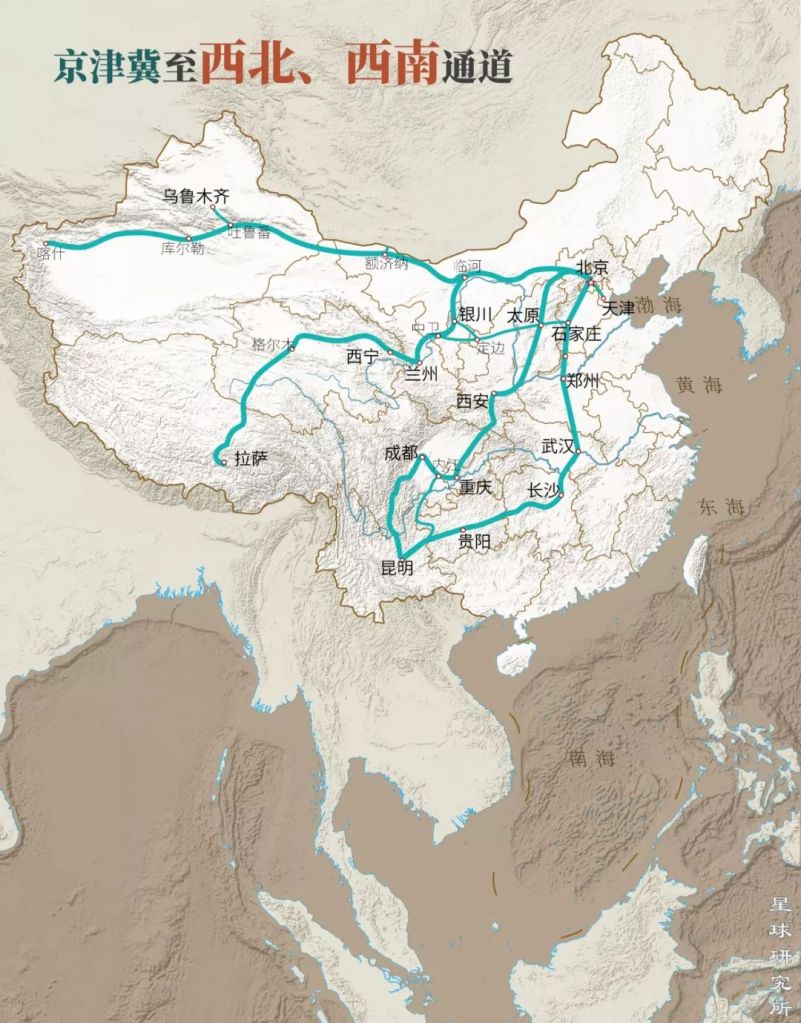

Thanks to them, the vast plains in the northwest and the Tibetan Plateau can remain closely connected to the capital regions. Together with the railroads in the southwest, they are the vital border passages for China.

Beijing (北京), Tianjin (天津), Shijiazhuang (石家庄), Zhengzhou (郑州), Wuhan (武汉), Changsha (长沙), Guiyang (贵阳), Kunming (昆明)

Taiyuan (太原), Xi’an (西安), Chengdu (成都), Chongqing (重庆)

Linhe (临河), Yinchuan (银川), Dingbian (定边), Zhongwei (中卫), Lanzhou (兰州), Xining (西宁), Golmud (格尔木), Lhasa (拉萨)

Ejina (额济纳), Turpan (吐鲁番), Korla (库尔勒), Urumqi (乌鲁木齐), Kashgar (喀什)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

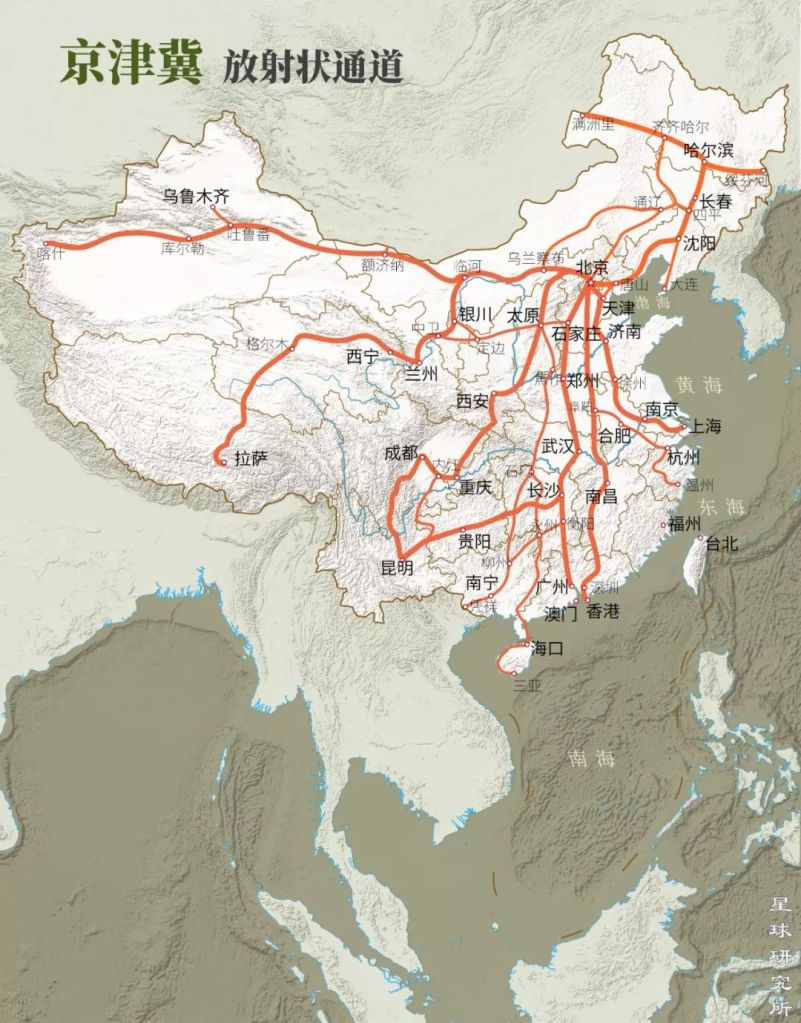

That marks the completion of the five major railroads that radiate from Jing-Jin-Ji Metropolitan Region to all key regions in the country.

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

But the Chinese were not stopping there.

A major railroad running from the west to east across the midlands of China was completed in 1953. This is the Longhai Railway. From east to west, it runs between Lianyungang in Jiangsu and Lanzhou in Gansu, and is a crucial transportation route between the Yangtze Delta and the northwest regions.

(photo: 武嘉旭)

And with the completion of Lanzhou-Xinjiang Railway, the Longhai Railway extended further west and rolled out of China through the Dzungarian Gate in Xinjiang. Travelling all the way to the distant Atlantic coast, this passage is widely known as the New Eurasian Land Bridge.

(photo: 杨诚)

The east-west railroad between Shanghai and Kunming finally took form when the entire Zhuzhou-Guiyang Railway was opened in 1975, which merges the railways between Shanghai and Hangzhou, Zhejiang and Jiangxi, and Guiyang and Kunming.

(photo: 潘永舟)

Another east-west railroad meanders up the Yangtze River, connecting Shanghai, Nanjing, Hefei, Wuhan, Chongqing and finally Chengdu. With several branch lines leaking out, this railroad takes care of the southwest regions and the midstream and downstream of the Yangtze River.

This is China’s first joint-stock railway, which received fundings from Ministry of Railways, local railway construction company and a Hong Kong company.

The construction of the railway was facilitated by Nan Huai-chin, a scholar originally from Wenzhou

(photo: 张一飞)

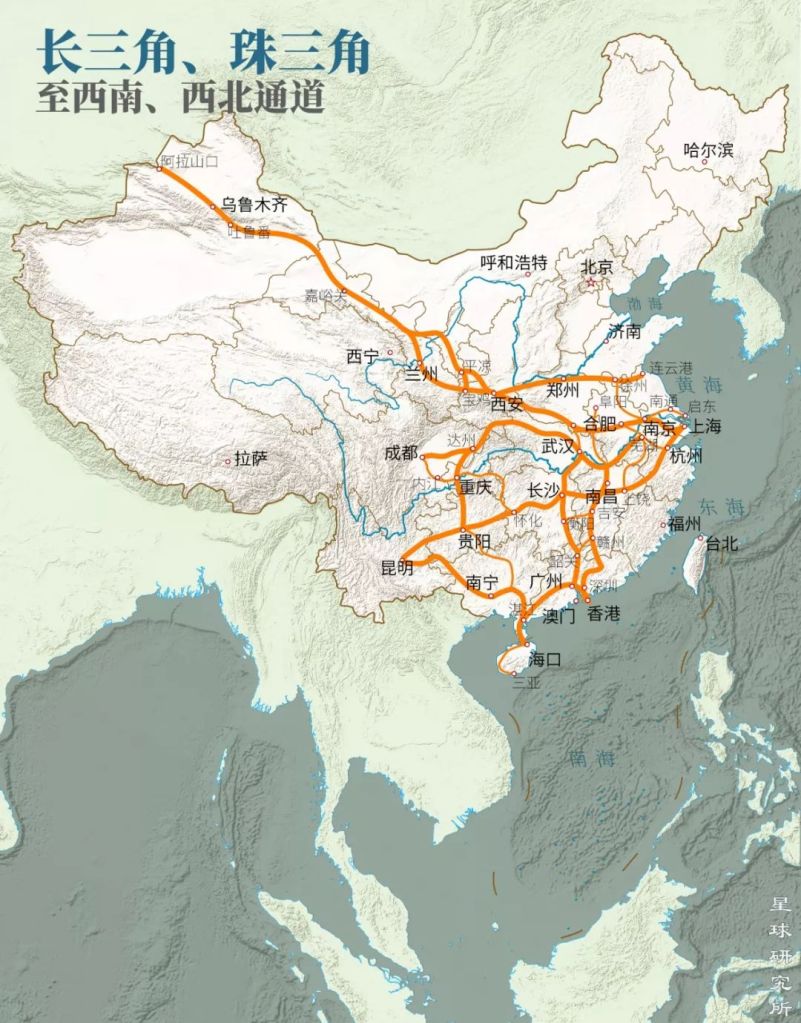

South China regions were not left out of the party.

The Litang-Zhanjiang, Guangzhou-Maoming, Nanning-Kunming and Chongqing-Guiyang Railways were built successively between 1955 and 2017, joining the southwest and the Pearl River Delta together. This completes the comprehensive network radiating from the two river deltas

Lianyungang (连云港), Xuzhou (徐州), Zhengzhou (郑州), Xi’an (西安), Baoji (宝鸡), Pingliang (平凉), Lanzhou (兰州), Turpan (吐鲁番), Urumqi (乌鲁木齐), Dzungarian Gate (阿拉山口)

Qidong (启东), Nantong (南通), Nanjing (南京), Fuyang (阜阳), Hefei (合肥), Wuhu (芜湖), Wuhan (武汉), Dazhou (达州), Chengdu (成都), Chongqing (重庆)

Shanghai (上海), Hangzhou (杭州), Shangrao (上饶), Nanchang (南昌), Changsha (长沙), Huaihua (怀化), Guiyang (贵阳), Kunming (昆明)

Ji’an (吉安), Hengyang (衡阳), Ganzhou (赣州), Shaoguan (韶关), Guangzhou (广州), Nanning (南宁), Shenzhen (深圳), Hong Kong (香港), Macau (澳门), Haikou (海口), Sanya (三亚)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

The construction of Nanning-Kunming Railway was particularly challenging. It climbs more than 2000 metres travelling from the Nanning basin to the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau. Along the way are sparsely populated regions with countless canyons and complex geological structures. Constructing a railway here was impossible without building bridges and excavating tunnels, which together account for almost 86% of the total mileage of the railway.

(photo: 王璐)

As the Nanning-Kunming Railway approaches Yiliang in Yunnan, it encounters and intertwines with the Kunming-Haiphong Railway which is more than 80 years older, like a pair of good friends from different generations sharing stories of their own eras.

(photo: 武嘉旭)

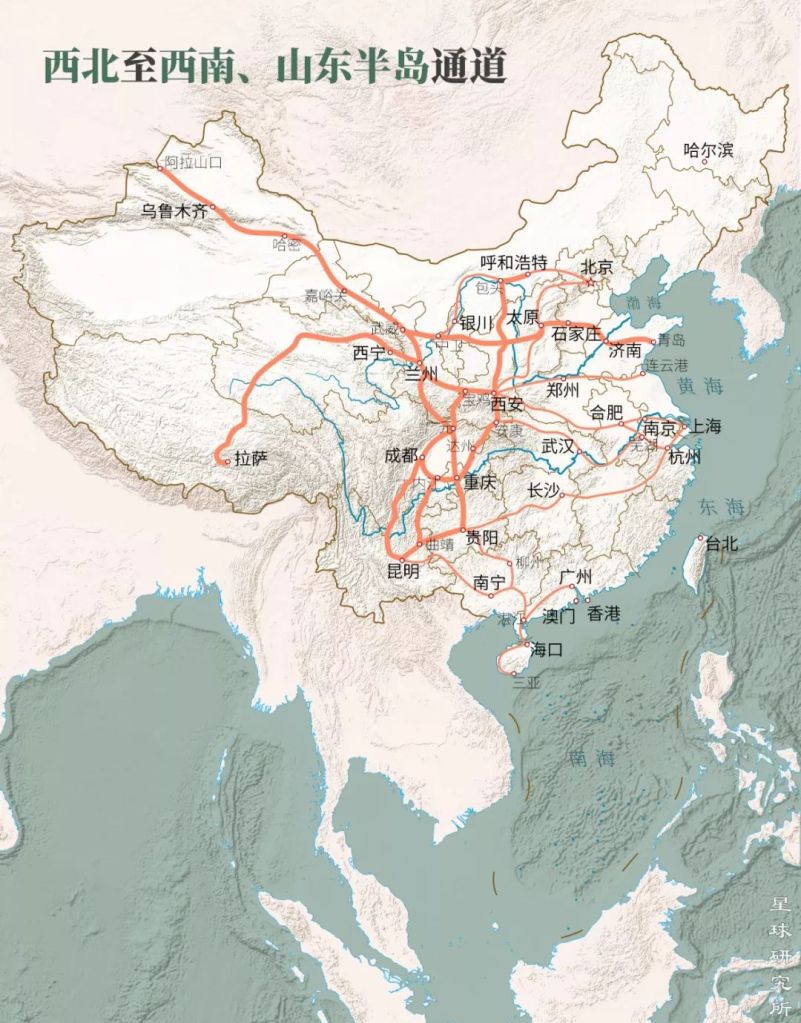

Coming on stage next is the southwest-northwest railroad. The Baoji-Chengdu Railway completed in 1958 hikes the Qinling Mountains on the 27 kilometres long spiral clusters.

Spirals are elongated railways that allow gradual gain in vertical elevation

(photo: 武嘉旭)

Half a century later, the Chongqing-Lanzhou Railway, completed in 2017, simply punches through the mountains with a 28-kilometre tunnel. These two railways overcome the Qinling Mountains from the east and west and have become the backbone for the southwest-northwest railroad. The route into Sichuan is no longer ‘dauntingly impossible’.

Owing to the integration of this railroad with the larger network in China, northwest provinces including Shaanxi, Gansu and Ningxia have become an important transportation hub that is closely connected to the southwest, inland and the coast.

Dzungarian Gate (阿拉山口), Urumqi (乌鲁木齐), Hami (哈密), Jiayu Pass (嘉峪关), Wuling (武陵), Zhongwei (中卫), Yinchuan (银川), Baotou (包头), Hohhot (呼和浩特), Beijing (北京)

Taiyuan (太原), Shijizhuang (石家庄), Jinan (济南), Qingdao (青岛)

Lhasa (拉萨), Xining (西宁), Lanzhou (兰州), Baoji (宝鸡), Xi’an (西安), Zhengzhou (郑州), Lianyungang (连云港), Hefei (合肥), Nanjing (南京), Wuhu (芜湖), Shanghai (上海), Hangzhou (杭州)

Guangyuan (广元), Chengdu (成都), Neijiang (内江), Chongqing (重庆), Dazhou (达州), Ankang (安康), Wuhan (武汉), Changsha (长沙)

Kunming (昆明), Qujing (曲靖), Guiyang (贵阳), Nanning (南宁), Liuzhou (柳州), Guangzhou (广州), Zhanjiang (湛江), Macao (澳门), Hong Kong (香港), Haikou (海口), Sanya (三亚)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

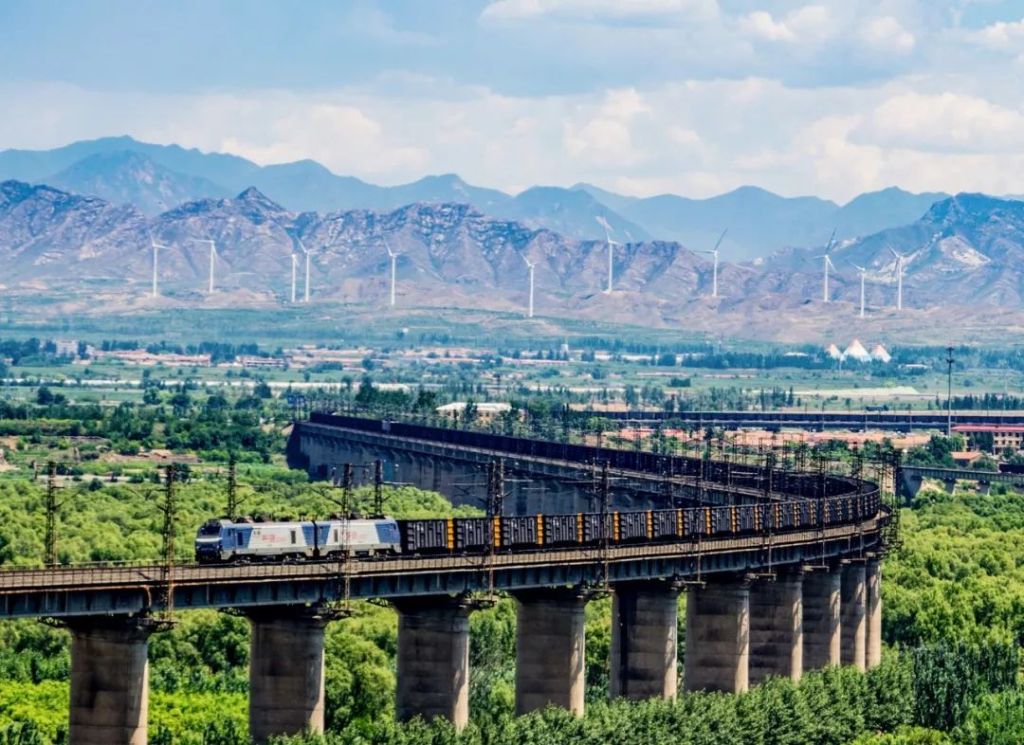

It took more than 140 years for Chinese railroads to start from zero, and grow from a few to many. Today, they are responsible for transporting steel, coal and timbers.

It is the first heavy-haul railway in China, and the freight capacity exceeded 400 million tons in 2010; because of the enormous self weight and heavy load, heavy-haul railways have more stringent requirements for trains, rails and power supply

(photo: 姚金辉)

And connecting cities, towns and villages.

(photo: 张一飞)

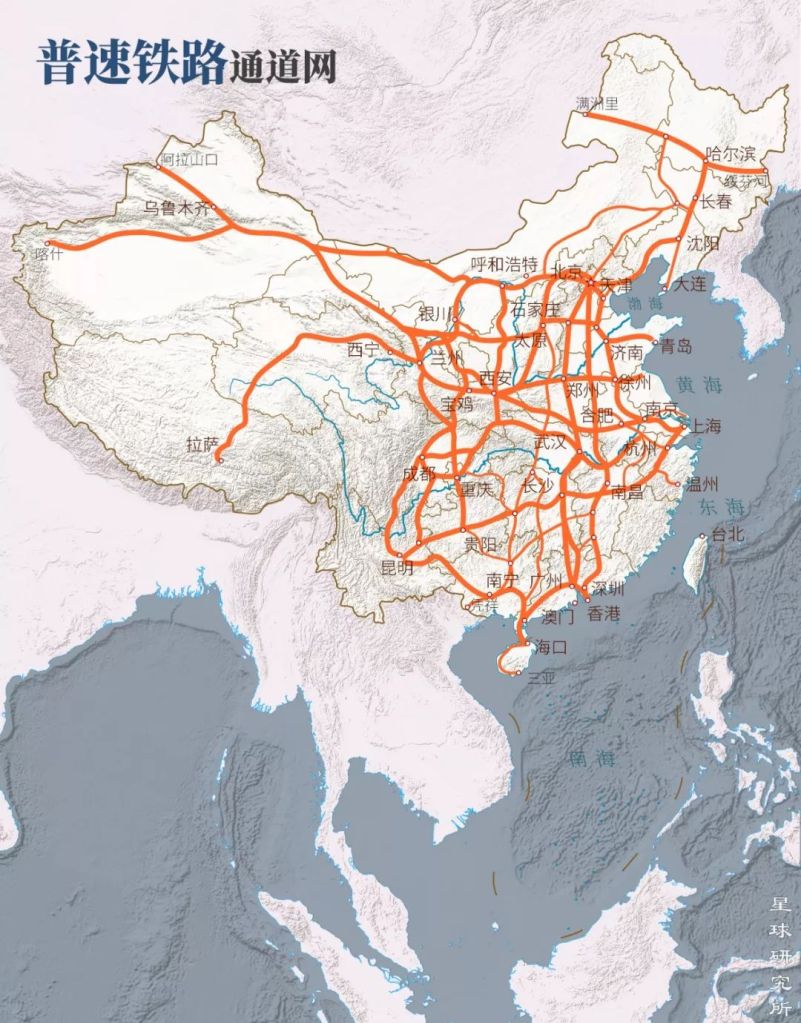

There are 12 general speed railroads in total, forming an enormous and intertwined network that spans the whole country.

The operating speed is normally under 200 km/h for these railways

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

But establishing an elaborate railroad network was never a smooth sailing. Before achieving the configuration we see today, China’s railroad had to go through another tough period.

2. Go faster, and even faster!

In 1993, China’s economy was riding on an express train, and saw an annual GDP growth of 13.9%. Unfortunately, neither passengers nor goods were on this train. Instead, they were stranded on the 60,000-kilometre railroad on which trains travelled only at 48 km/h. This travel speed was in stark contrast to the country’s astonishing economic growth rate, and even more so to the Japanese Shinkansen, which already achieved an average speed of 166 km/h and a maximum speed of 200 km/h 30 years earlier.

Developed in 1977 with a maximum travel speed of only 50 km/h, it was once the key locomotive for multiple routes including the Kunming-Hekou section

(photo: 贺磊)

The opening up and reform policy further catalysed the mass migration into all the major cities along the coast, where people abandoned their hometowns and fought for their dreams. The scale of nation-wide population mobility inflated rapidly, and the inadequacy of the existing railroad system became ever more apparent. Particularly during the Spring Festival travel seasons, it was practically impossible to get a ticket even with hundreds of extra temporary trains in operation.

Spring Festival travel season is always the busiest times

(photo: 徐小天)

In worst cases, the railroad system had to prioritise passengers over goods, which consequently dragged freight transportation into the same matter. This sadly coincided with the explosive growth in steel and coal production, both of which completely overwhelmed the growth in rail transportation capacity for goods. As a result, coal had to be transported on highways or sold locally.

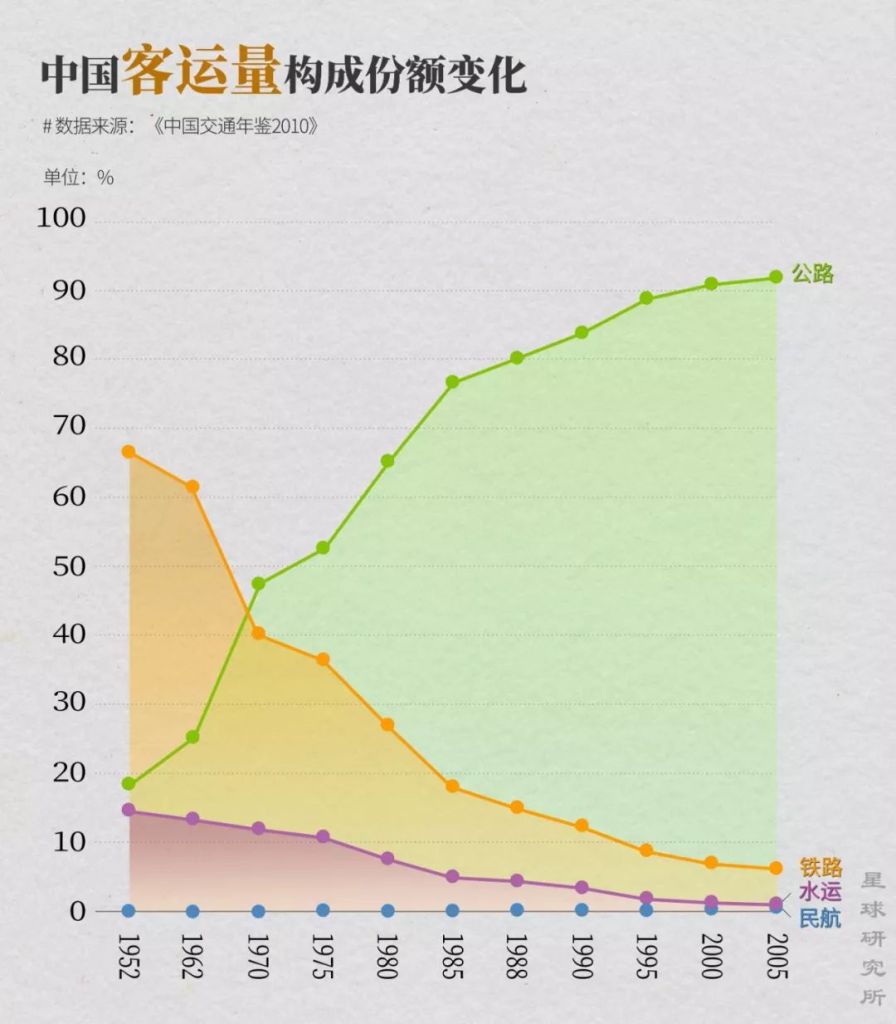

But this is a world where only the fittest survives. With the abrupt rise of highways and domestic flights, passengers made the obvious choice. The old and worn railroad system was taking its last breath.

Rail transportation (铁路) dropped markedly with the rise of automobile (公路), water (水运) and air transportation (民航)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

The last hope to turn the tide rested on the shoulders of railway speed upgrade programmes.

The Guangzhou Shenzhen Railway was the first to exceed a 160 km/h speed, which invited other sections to join the speed-up experiment, including the Shanghai-Nanjing, Beijing-Qinhuangdao, Shenyang-Shanhai Pass and Zhengzhou-Wuhan Railways. With the Shaoshan 8 locomotive coming into service, the first train in China to run at 240 km/h finally started operating on the Zhengzhou-Wuhan Railway.

(photo: 王璐)

The outcome of the preliminary speed upgrade was encouraging. Thus, the first China Railway Speed-up Campaign officially commenced on 1 April 1997. Starting with the three major routes, namely Beijing-Guangzhou, Beijing-Shanghai and Beijing-Harbin Railways, the campaign delivered 78 routes with a maximum speed of 140 km/h, which were capable of ‘leaving in the morning and arriving before sunset‘. They immediately reversed the plunging trend for passenger volume in the following year and secured the first victory for railroad system in years.

(photo: 房星州)

The subsequent speed-up campaigns progressed in full swing, and were completed in 1998, 2000 and 2001 respectively. The mileage involved reached 13,000 kilometres, which accounted for almost 20% of China’s total mileage.

The maximum speed of these trains were 160 km/h. Can it be even faster?

Glad you asked.

Since the conclusion of the fifth speed up campaign on 18 April 2004, four of the major routes, including Beijing-Shanghai, Beijing-Guangzhou, Beijing-Harbin and Longhai Railways, successfully hit the 160 km/h mark for freight transportation. And for passenger lines, the Z-series trains (Zhida-Tekuai, ZT, or literally ‘direct express’) started speeding at 200 km/h, which was just one step away from being classified as high-speed railway.

The initials of ZT trains coincided with the intimate nickname ‘zhu-tou’ (or literally ‘piggy head’), hence they are often referred to as piggy head trains; Dongfeng 11G trains were one of the piggy heads

(photo: 管俊鸿)

It was also this year when the exciting master plan of ‘Four Vertical and Four Horizontal’ railroad network was announced. This grand blueprint of China’s high-speed railway network was all ready for another major revolution.

On 8 December 2005, the very last steam locomotive in China proudly accomplished its final mission.

It was the last steam railway in China

(photo: 杨诚)

Just under two years later, the world-famous Hexie (literally ‘Harmony’) series high-speed trains were introduced to the world. Dashing at 250 km/h on 18 railways, they raised the total high-speed railway mileage in the country to more than 6000 kilometres almost overnight. From then on, China owns the longest high-speed railway network in the world.

High-speed railway is defined as a passenger railway with a designed speed of 250 km/h or above, and an operating speed of no less than 200 km/h

(photo: 吕威)

That concludes the chapter of railway speed upgrade, which lasted 10 years and completely renewed the railroad configuration in China. The glorious mission of ‘going even faster’ is now passed on to the high-speed railways.

3. High-speed Railway Era

Right before the 2008 Beijing Olympics, a brand new railway station with a glass dome ceiling rose from the grounds of southern Beijing less than 2 kilometres away from the Central Axis of the capital city.

This is the Beijing South Railway Station.

(photo: 刘慎库)

Born at the same time was the first high-speed railway in China to ever achieve a design speed of 350 km/h. Shuttling between Beijing and Tianjin, it spends merely 30 minutes for a one-way trip. This means that when you say goodbye to your friend and board one of these C-series trains, you will most likely arrive in another city 120 kilometres away before your friend even reaches home.

(photo: 焦潇翔)

The dazzling outcomes of the sixth speed-up campaign was fully reflected by the achievements of this Beijing-Tianjin Intercity Railway, which further stimulated the unstoppable development of high-speed railway in China. By the end of 2009, the Shijiazhuang-Taiyuan and Hefei-Wuhan Railways that run horizontally, and the Ningbo-Wenzhou-Fuzhou and Wuhan-Guangzhou Railways that run vertically were all completed and started operating.

(photo: Ealam)

Among them, the Wuhan-Guangzhou Railway leads the world of high-speed railway by spanning more than 1000 kilometres and running at a maximum speed of 350 km/h. What used to take 44 hours 70 years ago on the Guangzhou-Hankou Railway is nothing more than a 3 hour journey today on the Wuhan-Guangzhou Railway. We are embracing a whole new world.

(photo: 王璐)

Before the famous Beijing-Shanghai High-speed Railway joined the club, the 350 km/h squad had already welcomed 3 other members, which are the Zhengzhou-Xi’an, Shanghai-Nanjing and Shanghai-Hangzhou High-speed Railways.

Fuxing (literally ‘Rejuvenation’) series train running at the front

(photo: 刘慎库)

With the ground work for the ‘Four Vertical and Four Horizontal’ network in place, China’s ultimate railroad dream was gradually taking form. But which of these 8 backbone routes would be the first to run on full scale?

There was not even one better alternative.

Between Beijing and Shanghai, the old Beijing-Shanghai Railway has for a long time struggled to keep up with the ever-growing population and prospering economy, especially when both the passenger and freight volumes here are several times higher than the national average. High-speed railway is basically a must. Despite so, the construction of Beijing-Shanghai High-speed Railway somehow managed to spark intense controversy then.

Nevertheless, it did not disappoint us. Just 3 years after its completion, its annual passenger volume already exceeded 100 million.

(photo: 杨诚)

It also attained an experimental speed of 486.1 km/h on an operating railway, a record that remains unchallenged worldwide till this day.

It is the longest bridge in the world with a span of 165 kilometres

(photo: 王璐)

After that, the ‘Four Vertical’ backbone gradually acquired its full form with the completion of the Beijing-Wuhan section of the Beijing-Guangzhou High-speed Railway.

The 4 rails allow simultaneous operation of Beijing-Guangzhou High-speed and general speed railways

(photo: 田春雨)

The Harbin-Dalian High-speed Railway which travels through the frozen lands of blizzards.

It is the world’s first alpine high-speed railway running on high altitude and low temperatures

(photo: 刘慎库)

And the Hangzhou-Fuzhou-Shenzhen High-speed Railway that meanders along the southeast coast.

(photo: 刘慎库)

Beijing-Chengde section is still under construction

Beijing-Harbin (京哈客运专线), Beijing-Shanghai (京沪客运专线), Beijing-Guangzhou (京广客运专线) and Hangzhou-Fuzhou-Shenzhen High-speed Railway (杭福深客运专线)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

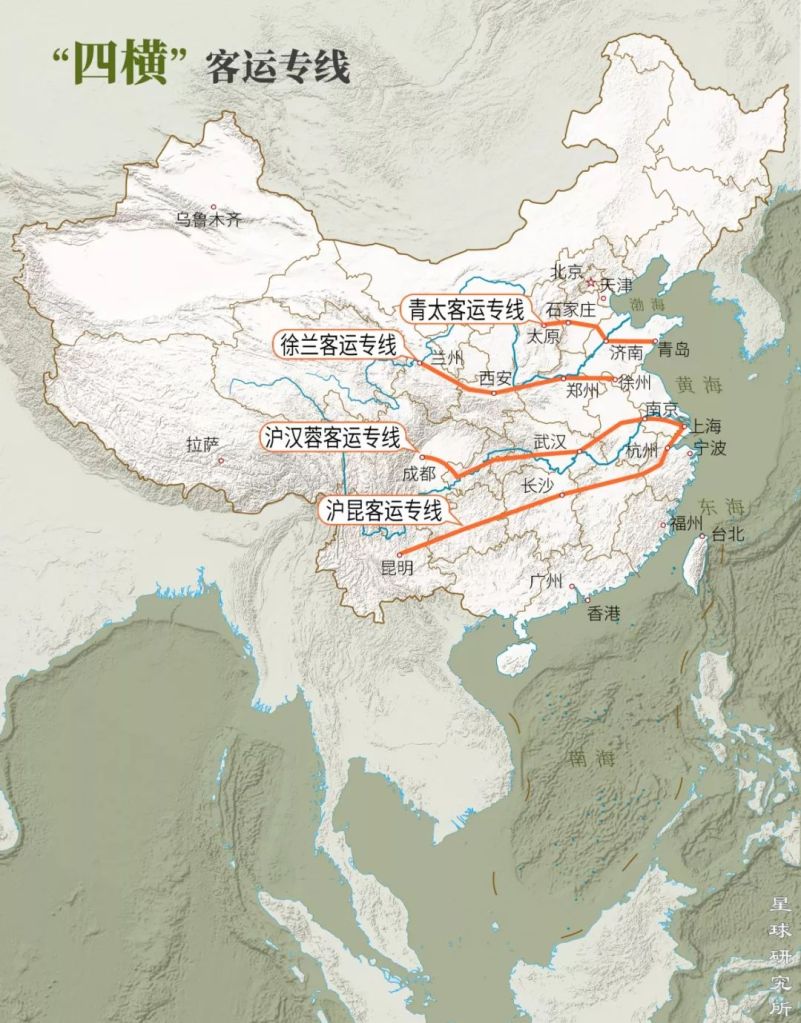

The ‘Four Horizontal’ network is also constantly maturing.

Qingdao-Taiyuan (青太客运专线), Xuzhou-Lanzhou (徐兰客运专线), Shanghai-Yuhan-Chengdu (沪汉蓉客运专线) and Shanghai-Kunming High-speed Railway (沪昆客运专线)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Spreading out in parallel, these four east-west railroads explore the mountains and valleys in the southwest.

(photo: 王璐)

And progress up the Yangtze River.

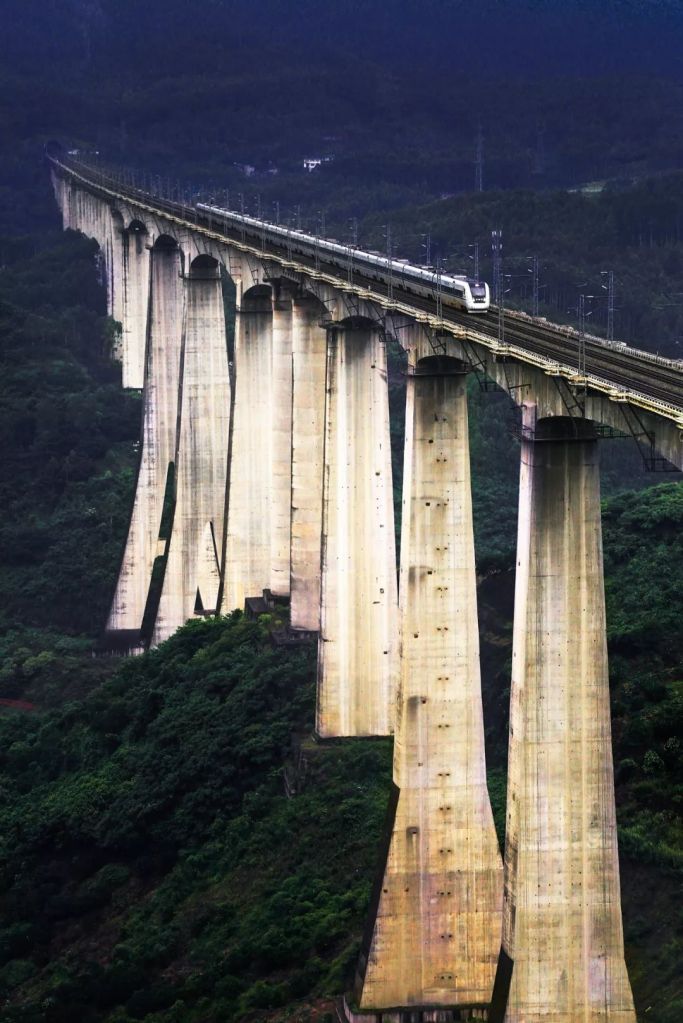

The maximum pier height is 139 metres, which is the world’s tallest pier for double-track railway bridge

(photo: 武嘉旭)

They also climb the Loess Plateau, speed across the Gobi Desert, tunnel through the Taiheng Mountain and run all the way to the coast.

Running in connection, the Xuzhou-Lanzhou and Lanzhou-Xinjiang Railways travel from Xuzhou, Jiangsu, all the way to Urumqi, Xinjiang

(photo: 赵伟森)

The connecting lines between the major routes are equally adventurous. The Guizhou-Guangzhou High-speed Railway, operating since 2014, was built on karst landforms, where complex terrains like sinkholes and caves are the norm.

(photo: 刘慎库)

The construction of Xi’an-Chengdu High-speed Railway was also extremely challenging. It runs through 11 tunnels that are all longer than 10 kilometres, and the climbing in elevation was touching the upper limit of modern railways. Completed in 2017, it was the first railway to traverse the Qinling Mountains.

The main line of the railway is in the tunnel, whereas arriving trains have to get around through the arrival and departure line; it is called ‘most special’ high-speed railway station

(photo: 武嘉旭)

The grand goal of constructing 16,000 kilometres of high-speed railway was achieved towards the end of 2014, which was 6 whole years earlier than planned. It was just a matter of time before the ‘Four Vertical and Four Horizontal’ network could run in full scale to show its true value, but Chinese engineers were still not satisfied. They pushed the plan further, and devised the even more visionary and ambitious railroad blueprint known as the ‘Eight Vertical and Eight Horizontal‘ network.

(photo: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

One hundred years ago, when China was enduring the hardships of railroad pioneering, Sun Yat-sen had said, ‘in today’s world, no country can thrive without railroads (今日之世界,非铁道无以立国)‘.

A century later, Chinese responded to this proposition by delivering an enormous and intertwined railroad network, which is comprised of 102,000 kilometres of general speed railway and 25,000 kilometres of high-speed railway. It has become China’s steel skeleton today, capable of transporting 3.7 billion tons of goods and 3 billion passengers around the country every year*.

*Based on data from 2017 Statistical Bulletin on China’s Railway

Train models (from left to right): CRH2C, CRH2A, DF11, HXD2B, SS9G (readers’ input)

(photo: 房星州)

This is a brief history of China’s railroad told by the 140 years of ups and downs.

It is also a diary about the rejuvenation of China written by railway tracks.

China’s first domestically designed and built railway

(photo: 张一飞)

The team would like to express their utmost respect to all railway engineers, workers and photographers.

Production Team

Text: 桢公子

Editing: 王昆,余宽,张天尧

Review: 风沉郁

References

历次《中长期铁路网规划》

孙永福主编《中国铁路建设史》

中国铁道博物馆《中国铁路发展史掠影》

高铁见闻《大国速度》等

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光

Fyi, the SS8 maximum speed is 140 km/h, not 240.

LikeLike

Yes, the actual operation speed is slower, at about 170 km/h max. Stated here is the experimental speed achieved in 1998.

LikeLike