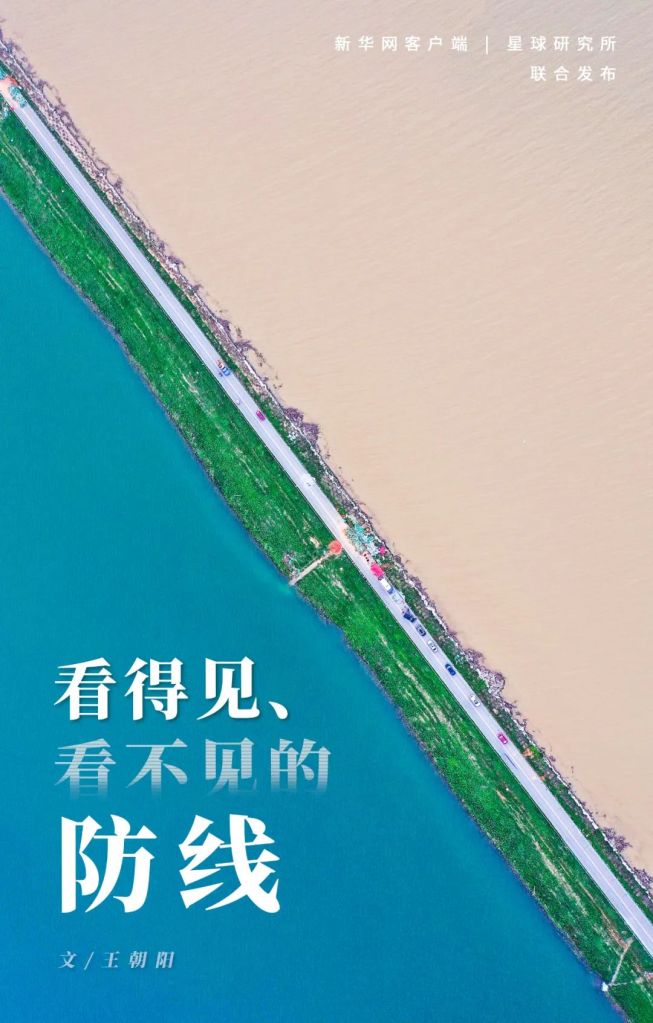

Original piece: 《长江防洪,有多难?》

Co-produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所) & Xinhuanet (新华网客户端)

Written by 王朝阳

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

The visible and invisible defence lines

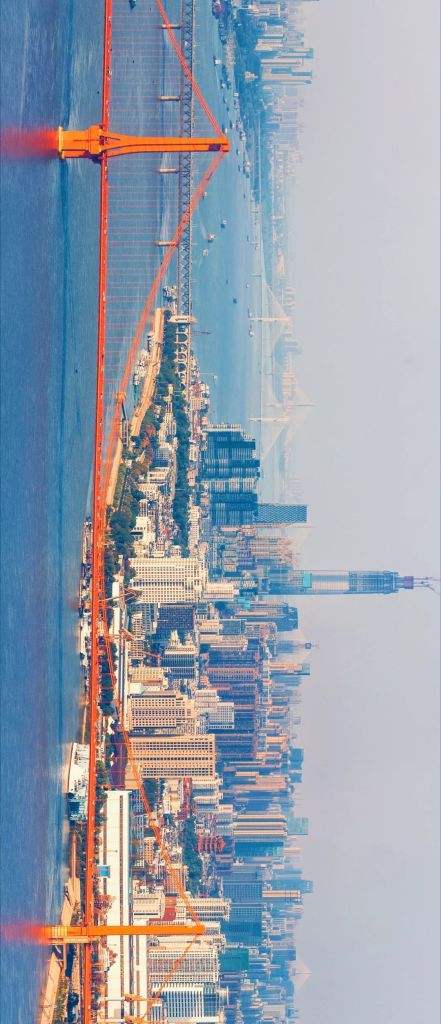

The Yangtze River.

Asia’s longest river.

Our Mother River.

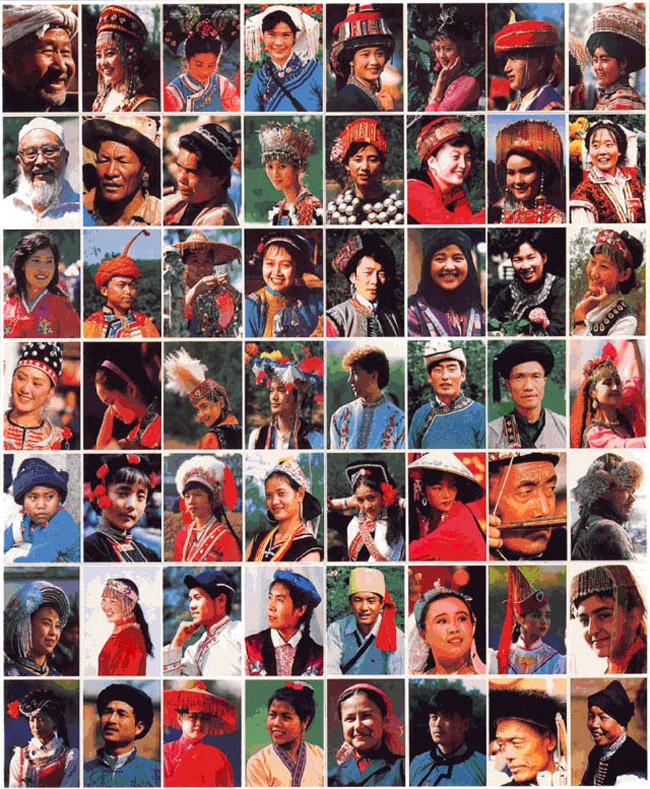

With over 10,000 tributaries and a third of the country’s total river runoff volume, the Yangtze River flows past 19 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions, nurturing 500 million people along the way.

(photo: 邓双)

But the frequent floods of Yangtze River can be catastrophic.

It killed 145,000 people in 1931.

33,000 in 1954

And 1526 in 1998.

*these data only include those stating flood as direct cause of death

Today in 2020, another deadly flood is knocking on our door.

How can we defend ourselves?

Half of the construction is submerged in the flood

(photo: 冯光柳)

1. Levees

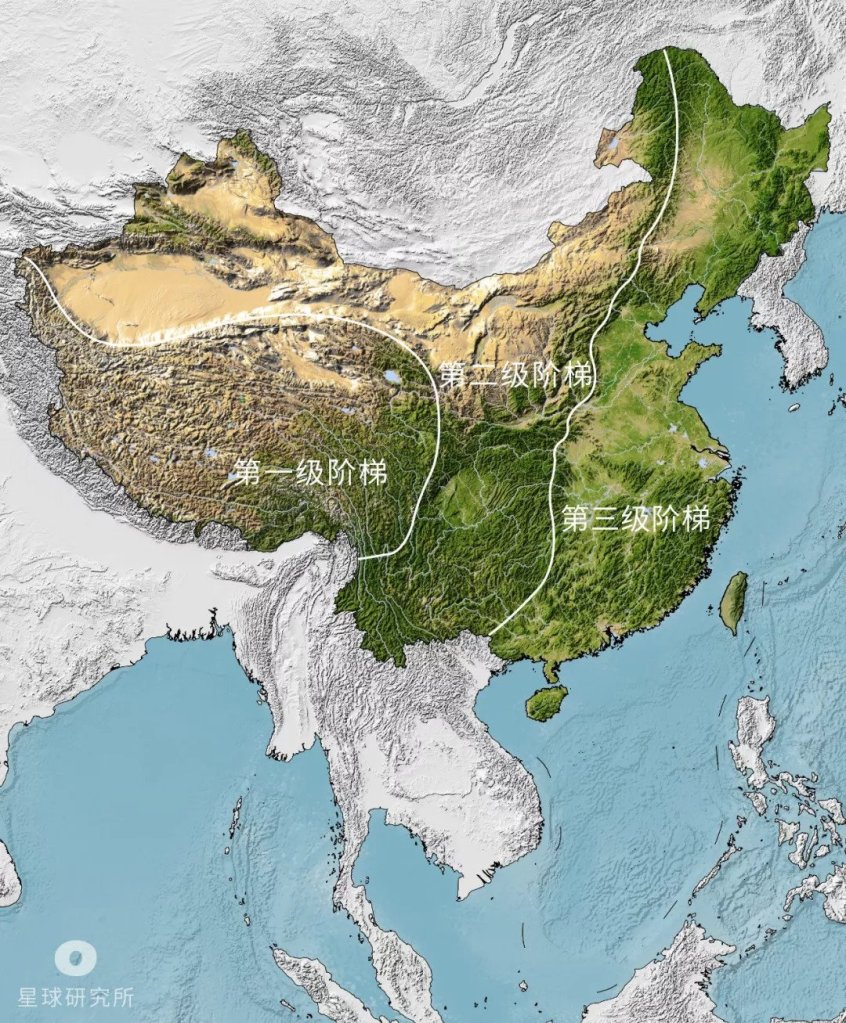

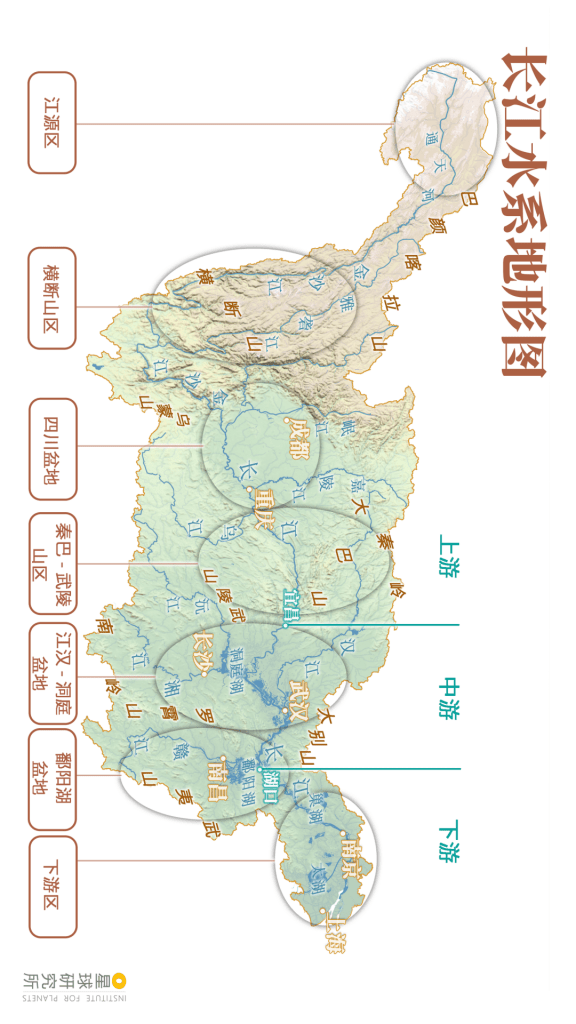

Originating in the Tibetan Plateau, the magnanimous Yangtze River accommodates thousands of tributaries throughout its east-bound journey towards the sea. The entire river basin can be topographically divided into seven regions.

Headwater region (江源区), Hengduan Mountains (横断山区), Sichuan basin (四川盆地), Qinba-Wuling Mountains (秦巴-武陵山区), Jianghan-Dongting basin (江汉-洞庭盆地), Poyang Lake basin (鄱阳湖盆地), downstream region (下游区)

Upstream (上游), midstream (中游) and downstream (下游)

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

The headwater region in the far west is dry and frosty. This uninhabited highland allows the river channels to spread out and run totally unobstructed.

(photo: 刘夙培)

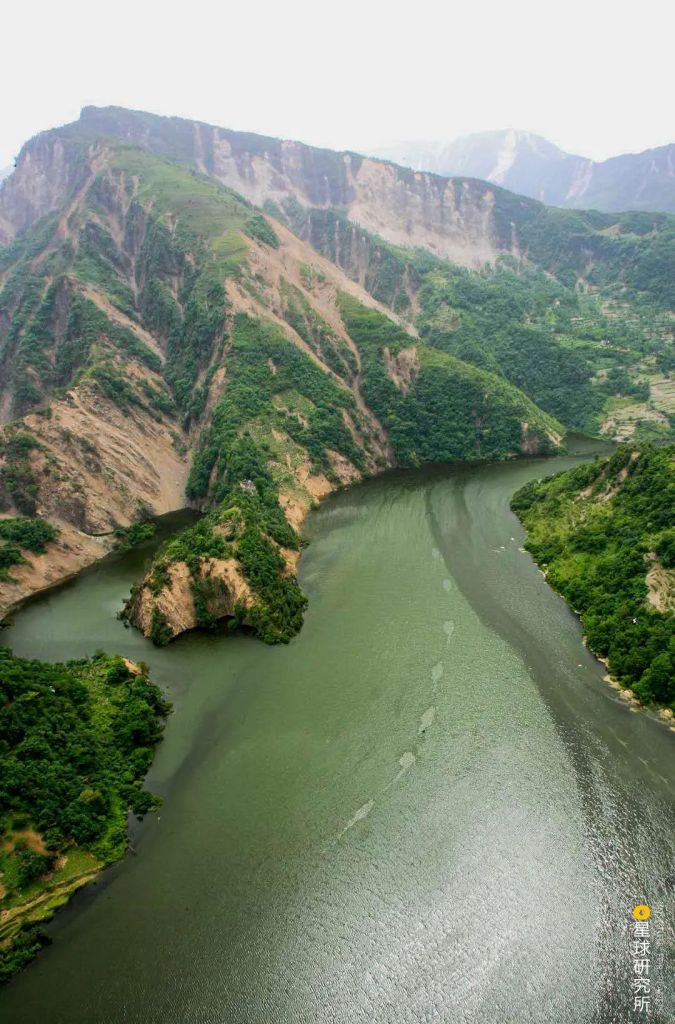

Along the Hengduan and Qinba-Wuling Mountains, the river is sandwiched by steep cliffs and deep valleys. With a restricted channel, flood water is relatively harmless in these regions.

(photo: 李祺)

The towns and villages here are sitting well above the water level, and hence do not require tall levees. Rather, they should be more worried about mudslides during rainstorms.

(photo: 君子裕)

While the relatively depressed Sichuan basin funnels water from all directions, the river cuts deep into the land as the water courses downslope. Floods therefore only affect a few neighbouring regions.

(photo: 水手郑志华)

The downstream region in the east flows through the Hukou County of Jiangxi before it reaches the mouth. In between, there are no major tributaries joining the mainstream, and the channels are wide and deep. With the East China Sea on the right, floods can easily be drained.

Therefore, major floods in this region seldom build up locally. They usually come from the upstream and midstream, and the most vulnerable location of all is the Anhui section in the middle reaches.

(photo: 张浩然)

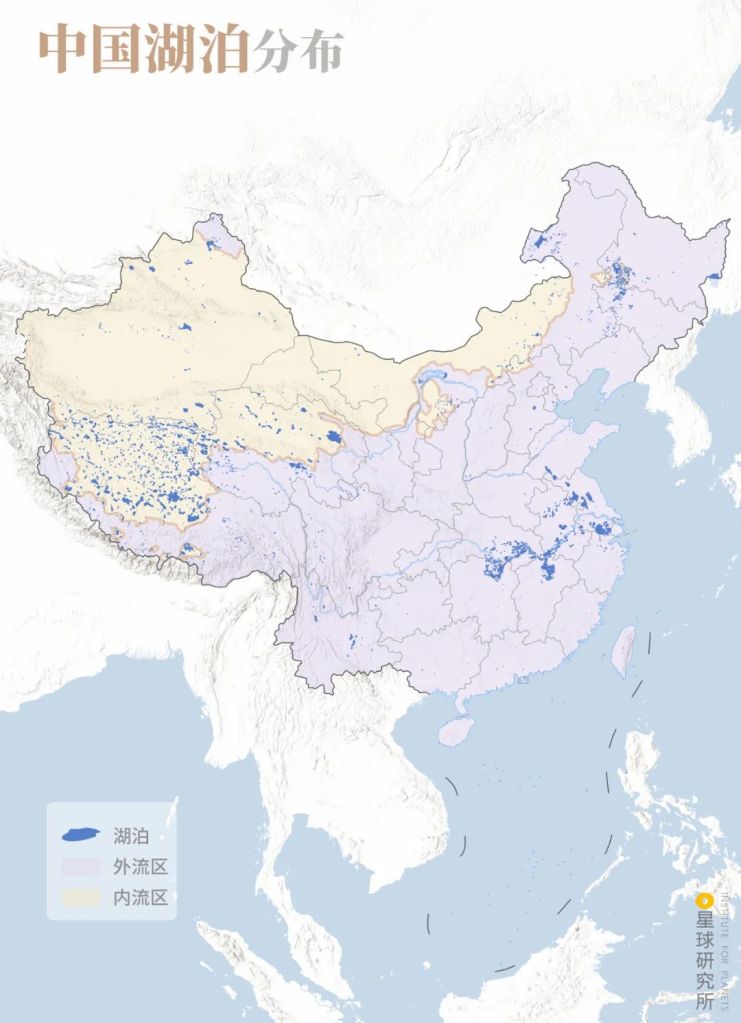

The heartlands of Jianghan-Dongting and Poyang Lake basins fare the worst among any other regions. Elevation here is generally low, at around 20-40 metres in the former and just 10-30 metres in the latter. Surrounded by mountains, all rivers in these basins, large and small, converge at the centre.

Jianghan-Dongting basin (江汉-洞庭盆地), Poyang Lake basin (鄱阳湖盆地)

Dongting Lake (洞庭湖), Poyang Lake (鄱阳湖)

(diagram: 陈志浩 & 郑伯容, Institute for Planets)

River water and the sediments that come with it create fertile lands along the banks. These regions are always densely populated and have a prospering economy.

(photo: VCG)

But rivers flow slowly in basins, and thus are prone to overflow.

During flood seasons, water levels in both the river mainstream and tributaries rise rapidly due to the joint effects of flood drainage in the upstream, local rainstorms and the backwater coming from downstream.

In addition, the exploding population has led to large-scale lake reclamation for farming. Many lakes with flood control capacity have since shrunk substantially or even disappeared.

The flood water has nowhere to go but to leak out.

They are located in the southeast of Poyang Lake

(photo: VCG)

To avoid that, people living in these basins have been building levees along the banks ever since the Eastern Jin Dynasty. This is the first line of defence against floods.

However, these levees not only restrict water flow, but also the outflow of sediments that used to fertilise the land. This causes excessive deposition in and elevation of the river bed, which warrants further heightening of the levees, resulting in a vicious cycle.

Built in Ming Dynasty, the foundation of the pagoda is more than 7 metres below the dike surface due to numerous dike heightening

(photo: 邓双)

Owing to limitations in technology and financial status, early levees were weak and unreliable, and pretty much collapsed with every flood.

When raging floods tear open the levees, they scour the land surface and often dig metres-deep pools and waterways. They cruelly destroy every building and farm standing in their way and submerge large areas of land.

An unimaginable tragedy for everyone living there.

Yichang (宜昌), Jingzhou (荆州), Changde (常德), Yiyang (益阳), Yueyang (岳阳), Xianning (咸宁), Wuhan (武汉), Xiaogan (孝感), Ezhou (鄂州), Jiujiang (九江), Nanchang (南昌), Anqing (安庆), Tongling (铜陵), Wuhu (芜湖), Nanjing (南京), Zhenjiang (镇江)

Yellow arrow: levee breaches; red arrow: flood diversion

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

The 1931 flood in the midstream and downstream of Yangtze River caused 145,000 deaths, including 66,000 in Hubei and 47,000 in Hunan. And the 1954 flood in the same region killed 33,000 people, where 31,000 of them were from Hubei alone.

The scars left by devastating levee failures can remain for more than hundreds of years.

It was formed during the levee failure in Wencun in 1842

The deep pool (深潭) and waterways (水道) are used as fish ponds and paddy fields respectively

Wencun (文村), Great Dike of Jingjiang (荆江大堤), Gongan (公安县城), Jiangling (江陵县城)

Since the establishment of New China, and especially after the great floods in 1954 and 1998, all the major levees were strengthened and expanded into a comprehensive defence system with a total length of 64,000 kilometres.

The longest sections are in Hubei, Hunan, Jiangxi and Anhui.

These include the 3900 kilometres long Yangtze Levee.

Flood water was close to overtopping the Yangtze Levee

(photo: 陈肖)

Tributary levees along Han River, Xiang River and Gan River.

There are shelter forests distributed on both sides of the levee

(photo: 李念)

And lake levees encircling Dongting Lake and Poyang Lake.

The levee maintained a clear water body and a low water level in the Pearl Lake

(photo: VCG)

As well as urban levees.

Citizens were taking a walk on the flood wall

(photo: VCG)

Most of the levees in the two major basins have become the highest elevation points in cities and villages. They loyally defend these densely populated areas on the vast plains from rampaging floods.

Right here, the notorious Jingjiang section of the Yangtze River meanders wantonly.

Jingjiang section refers to the river basin between Zhicheng Village in Yichang and Chenglingji in Yueyang

Yueyang, Hunan (湖南省岳阳市), Dongting Lake (洞庭湖), meandering Jingjiang (九曲荆江), Jianli, Hubei (湖北省监利市)

(photo: 蓑笠张)

The water level in Jingzhou frequently rises above 40 metres. It even reached 45.22 metres in the 1998 flood, while the elevation of most parts of the city is below 35 metres.

As the old saying goes, ‘the thousand-mile Yangtze River kills at Jingjiang (万里长江,险在荆江)’. Local people’s lives really depend on a strong levee here.

It rises up more than 10 metres above the city

(photo: 邓双)

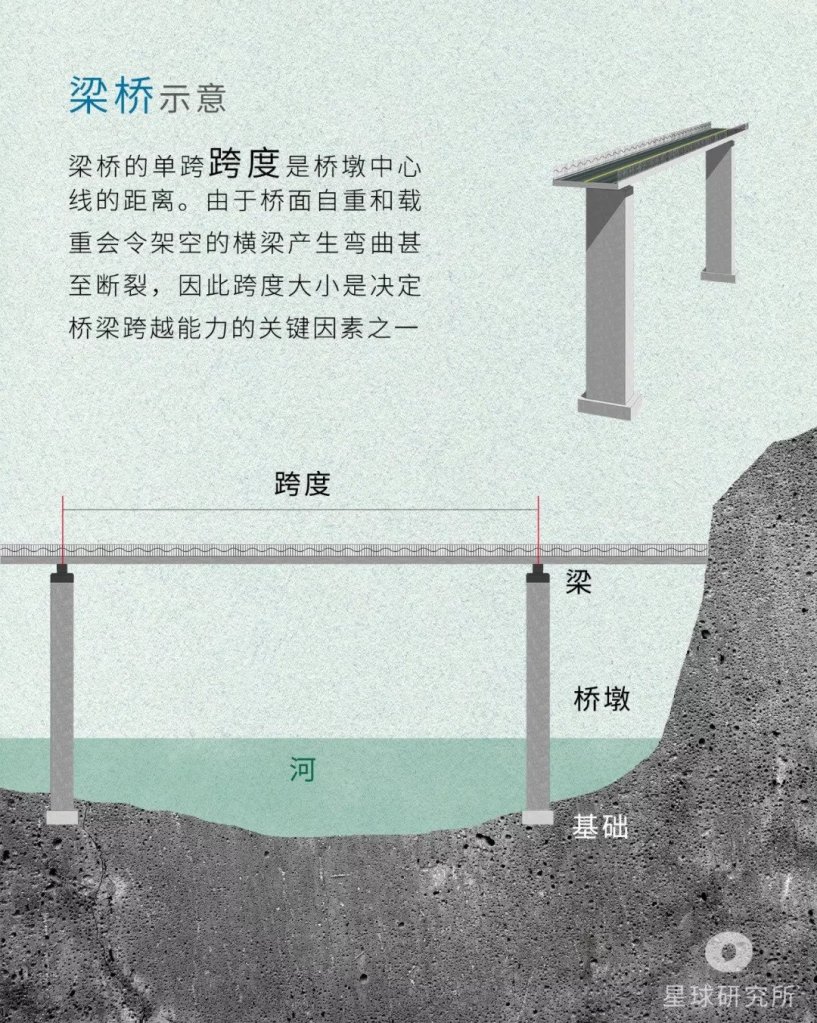

The height of a levee is generally determined based on the highest flood water level in history. This is the design flood level, also known as the control flood level.

Depending on the purpose and criticality of the levee, it has to be at least 1.0-2.5 metres taller than the design flood level to make sure the flood water does not overflow.

The flood that submerged the river banks was almost brushing at the design flood level on the top of the levee

(photo: 向源翰)

Levees are trapezoidal structures with artificial earth fill. The foundation as well as the levee body often contain sand layers. These are prone to seepage due to imperfect filling, which destroys the levee. Therefore, vertical anti-seepage walls are sometimes embedded in the levee to prevent it from collapsing.

‘Water level’ in this piece generally refers to Elevation of Wusong (吴淞高程), where Elevation of Wusong-Huanghai Elevation (黄海高程) ~1.7 metres

Silty loam (粉质壤土), silt (粉细砂), silty clay (粉质粘土), clay (粘土), sandy loam (砂壤土), coarse sand (中粗砂), artificial earth fill (人工填土), observation unit (观望房)

Huanghai Elevation (黄海高程), design flood level (设计水位)

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

And for Wuhan, which has two rivers and faces four river banks, the urban area is too close to the water to provide sufficient space for levee construction, hence limiting the height of levees. Engineers can only add a flood wall on top of the existing soil embankment.

The flood has already submerged the river promenade, approaching the city with just the flood wall in between

(photo: VCG)

Flood walls are mainly made of concrete. They erect along the banks and occupy much less space compared to artificial earth fill levees. The wall can rise up to 3-5 metres above ground.

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

River regulation projects were implemented simultaneously with the construction of levees and flood walls. These include the Lower Jingjiang Meander Cut-off Project, which reduces river sinuosity and allows an accelerated water flow.

While it leads to a more efficient local flood drainage, the project puts more pressure on the downstream flood control.

Zhongzhouzi (中州子) and Shangchewan (上车湾) are artificial meander cutoffs (人工裁弯)

Lower Jingjiang section refers to the section downstream of Ouchikou (藕池口)

Meanders: Ouchikou, Diaoxiaokou (调弦口), Shangchewan, Chibakou (尺八口)

Cities: Shishou (石首), Huarong (华容), Jianli (监利)

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

After the levee strengthening and river regulation measures, levee breaching had rarely occurred in the main stream and tributaries of Yangtze River ever since 1954. But the downsides of tall levees are the high construction cost, substantial land use and the negative impact on everyday life. These set an upper limit on the flood control potential of levees.

For instance, the levees in Jingjiang section of the Yangtze River is only designed for 10-year floods*, whereas those in Wuhan section can at most withstand 20- to 30-year floods. They are even more fragile in some tributaries, and can barely protect lives and properties next to the river.

We need a second line of defence.

* N-year floods refers to the probability (1/N) of a flood occurring at a given scale. It does not infer that the flood is expected to occur only once in N years

After the bursting of Fushui River, helicopter pilots attempted to block the breach by hoisting net bags and airdropping rocks

(photo: VCG)

2. Reservoirs

When the flood-carrying capacity of Yangtze River is overwhelmed by the ferocious water, reservoirs in the upstream becomes the crucial flood regulator that alleviate the pressure in the leveed downstream channels.

The most famous of all is of course the Three Gorges Dam.

It turns into a reservoir when arresting flood water

(photo: VCG)

Owing to the recurrent and devastating floods in Yangtze River, the top mission of the Three Gorges Dam is actually not power generation.

The hydropower generator in Three Gorges Dam has an installed capacity of 22.5 million kW. Despite having a much higher installed capacity than the previous world champion Itaipu Dam (14 million kW), the two dams generate comparable amount of electric power.

This is because much of the capacity of Three Gorges Dam is invested on the arduous task of flood control.

(photo: 李心宽)

Each year, the water level in the Three Gorges Reservoir is raised to the standard mark at 175 metres during the winter half-year period, which corresponds to a storage volume of 39.3 billion cubic metres.

This volume far exceeds that of Poyang Lake, and the elevation drop of more than 100 metres for the ample amount of water allows the dam to generate enormous load of electric power.

But before 10 June every year, the Three Gorges Reservoir has to discharge excess water and lower the water level to the flood period mark at 145 metres and give up plenty of storage capacity for the upcoming floods.

Letting go a lot of water during entire flood periods is the reason for the submaximal power generation.

(photo: VCG)

The storage capacity assigned for flood control in the Three Gorges Reservoir is 22.15 billion cubic metres, which is more than half of the total storage.

Earlier this year in July, the hydrological stations at Dongting Lake and Poyang Lake recorded a critical water level that was closing up with the design flood level.

Lower parts of the Luoxing Stone was already submerged

(photo: VCG)

The Three Gorges Dam immediately reduced the drainage flow and arrested 3 billion cubic metres of flood water within one week. That temporarily saved the two lakes from the precarious situation.

But it is unrealistic to rely solely on the Three Gorges Dam to solve all the flood problems. Therefore, more than 50,000 reservoirs were built over the past decades. Cumulatively, they possess a storage capacity of more than 360 billion cubic metres. This is equivalent to having 9 Three Gorges Dams.

Together they form a super reservoir cluster.

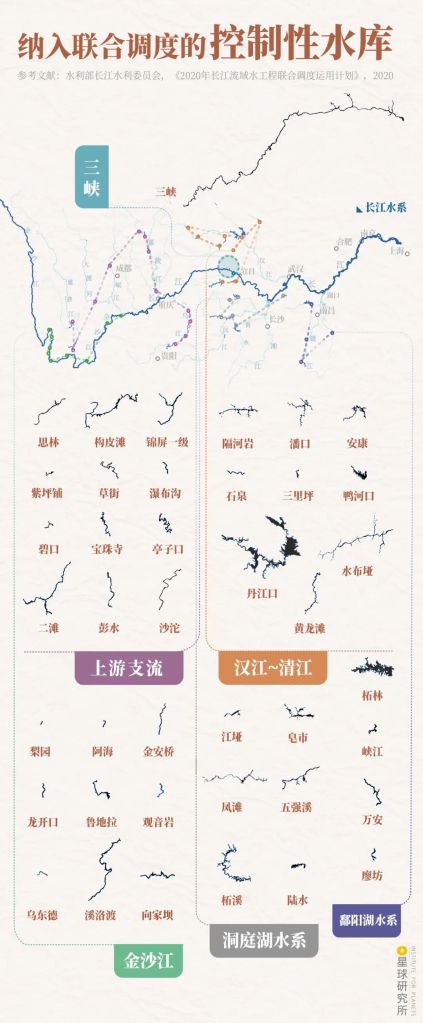

Among them, the 41 controlled reservoirs are able to store up to 59.8 billion cubic metres of water in total, which is twice the volume of the Poyang Lake.

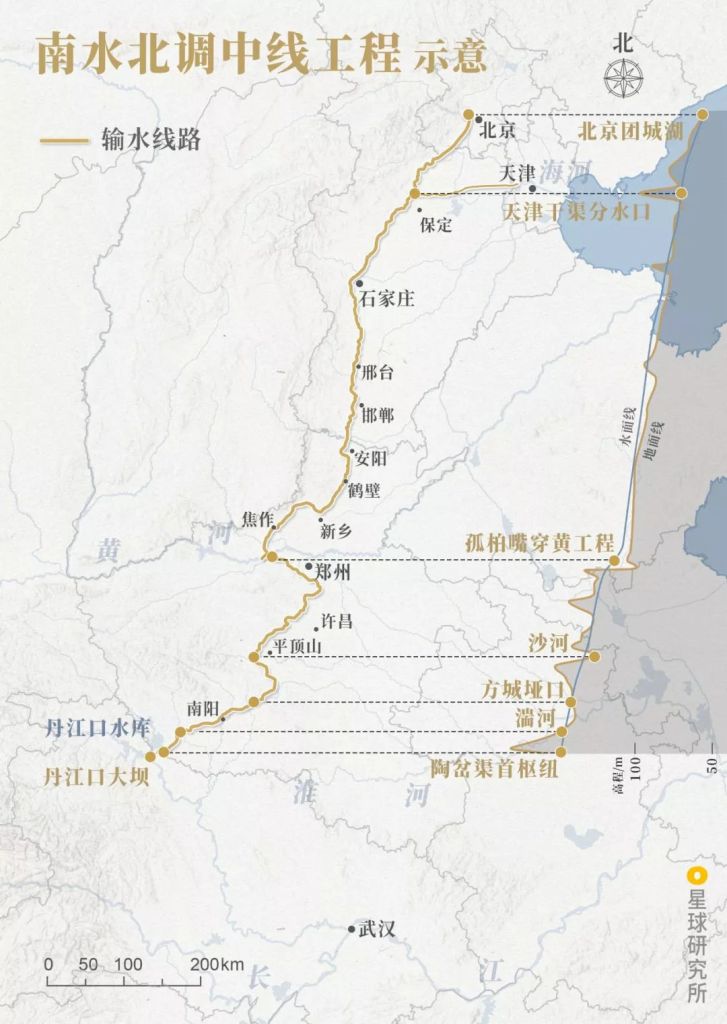

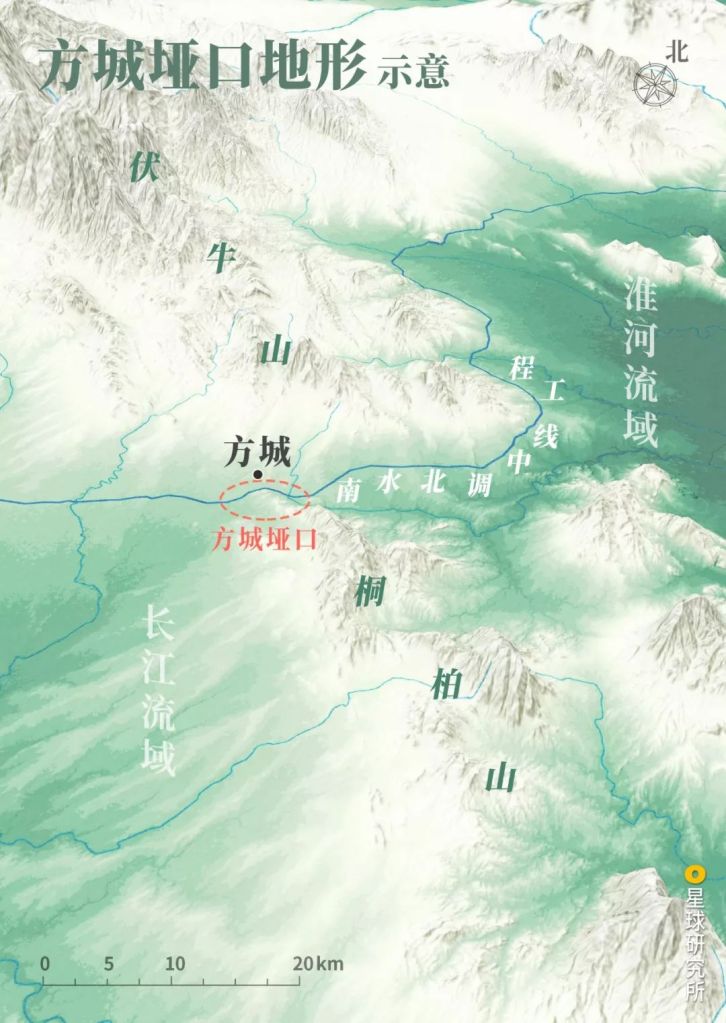

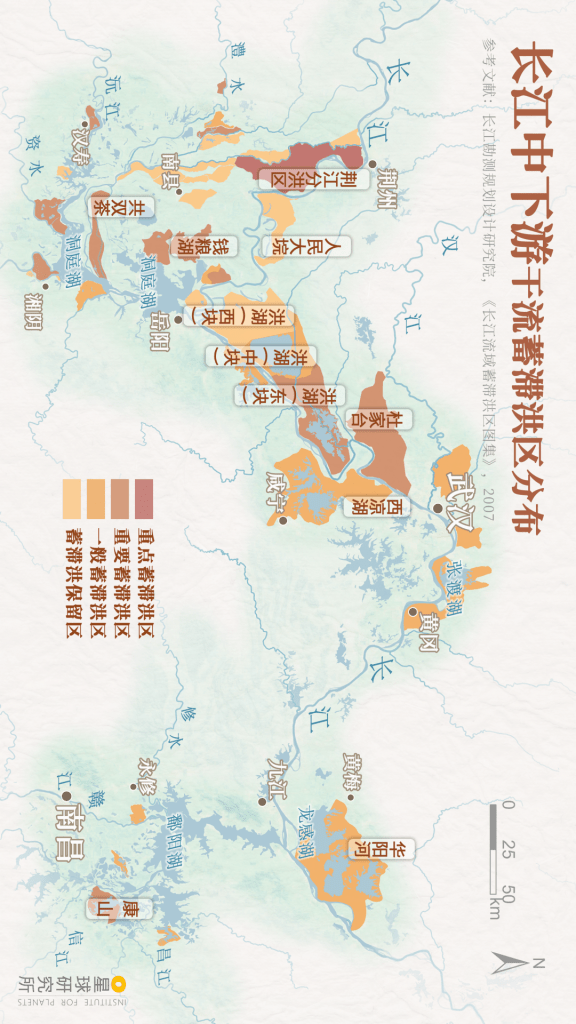

Major systems: Three Gorges (三峡), upstream branches (上游支流), Jinsha River (金沙江), Han River-Qing River (汉江-清江), Dongting Lake system (洞庭湖水系), Poyang Lake system (鄱阳湖水系)

(diagram: 陈志浩 & 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

These include the Ertan Dam and Jinping-I Dam on the Yalong River and Xiluodu Dam on the Jinsha River.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

Xiangjia Dam and Wudongde Dam.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

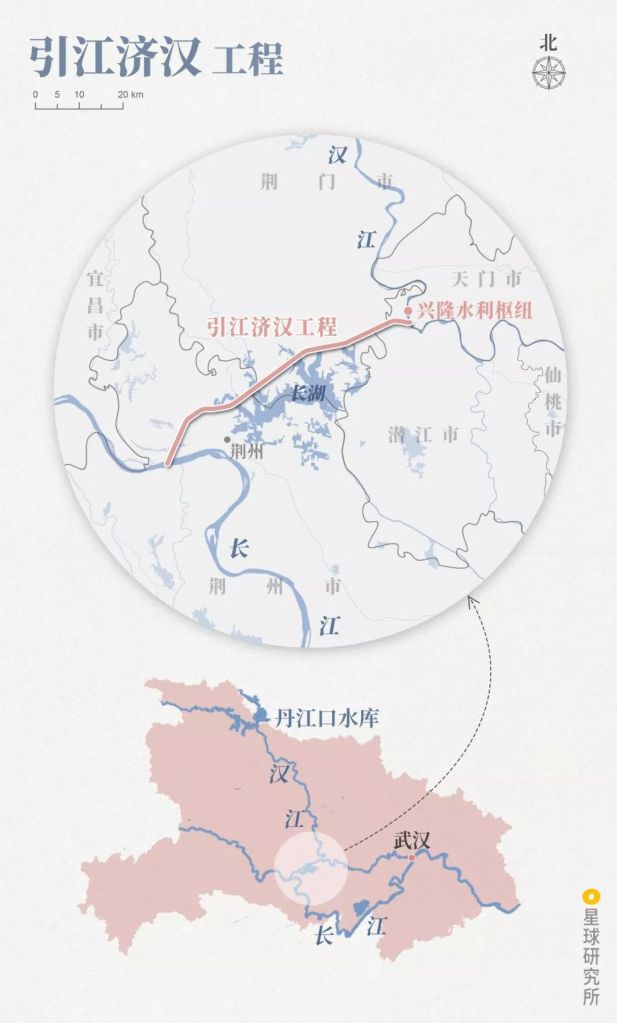

As well as the Danjiangkou Reservoir on the Han River, Geheyan Dam and Shuibuya Dam on the Qing River, and the Wuqiangxi Dam on the Yuan River.

(photo: VCG)

By implementing this joint scheduling reservoir system, the flood control standard has now been raised from 10-year floods to 100-year floods. This capability is much better than just having the levees alone, and makes the flood control in the downstream much more flexible.

This is also why we are no longer as passive and struggling as much as in 1998 when faced with floods in recent years, despite at equally high frequency.

Comparison between different submerged areas in the 1870 flood in the presence and absence of Three Gorges Dam

Cities: Yichang (宜昌), Jingzhou (荆州), Shishou (石首), Changde (常德), Yiyang (益阳), Changsha (长沙), Yueyang (岳阳), Jianli (监利), Xiantao (仙桃), Xianning (咸宁), Wuhan (武汉), Xiaogan (孝感)

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

Furthermore, to avoid reduction in reservoir storage volume due to soil deposition, key preventive projects on soil and water conservation were implemented at the same time. Programmes such as afforestation and returning farms to forests and prairies are certainly instrumental in mitigating erosion along the Yangtze River basin.

(photo: VCG)

But let us be clear about one thing: even having several tens of thousands of reservoirs will not help us tame the defiant Yangtze River.

First of all, the existing storage volume for flood control is nothing compared to the 1 trillion cubic metres runoff volume of the Yangtze River. It is impossible to indefinitely increase the storage volume given how much land a reservoir occupies.

This price is too high for a densely populated country like China.

(photo: VCG)

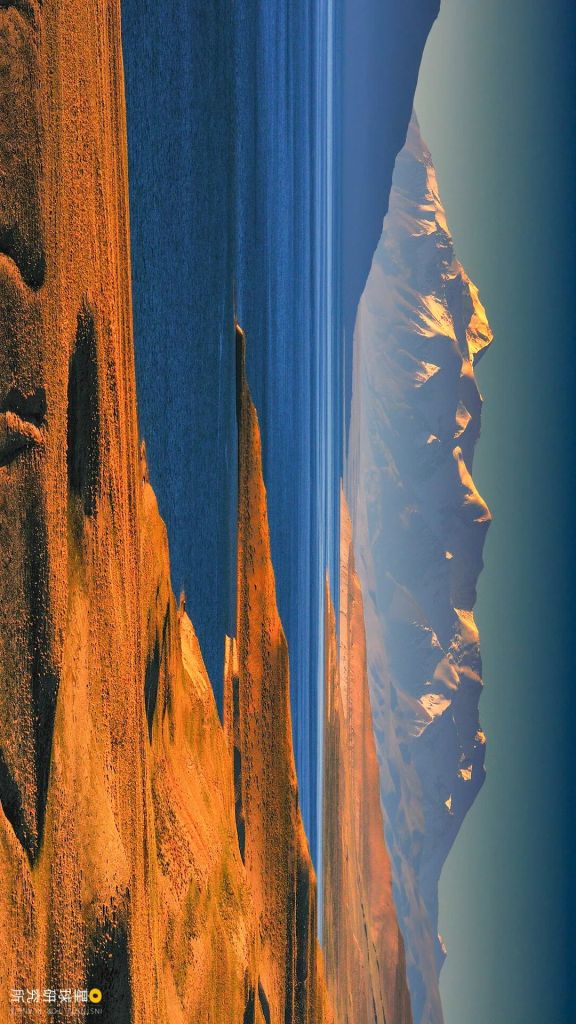

Second, these reservoirs are mostly distributed around the upstream regions of Yangtze River. For the midstream and downstream where torrential rain and floods are most severe, however, reservoirs can hardly be built due to the flatness of the local terrains.

Even with an enormous reservoir like the Three Gorges Dam, the effect of flood control will be modest for distant regions further downstream of Wuhan.

(photo: 李云飞)

Therefore, we need the third line of defence.

3. Flood retention and detention basins

When even the levees and reservoirs cannot protect us from the menace of the rampaging Yangtze River, flood retention and detention basins will be deployed.

They are low-lying regions surrounded by tall gated levees. Normally, floods are kept out from these regions, but when the time for flood diversion comes, these gates will open wide to invite the wolf into the house.

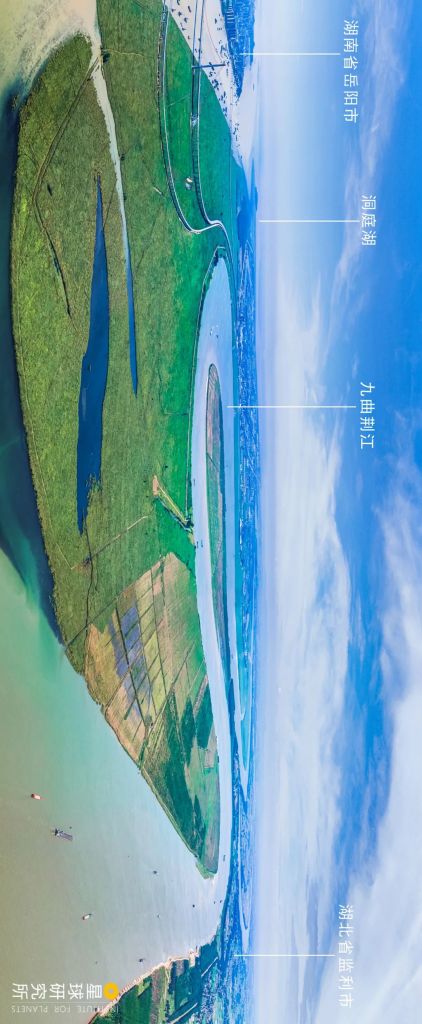

Bottom right is the Kangshan flood retention and detention basin behind the levee, top left is the Poyang Lake

(photo: VCG)

In the 1870 flood, the flood peak in the Yichang mainstream once reached 105,000 cubic metres per second, far exceeding the flood-carrying capacity of the Jingjiang section.

But the section cannot be blamed, because such a massive flow is capable of filling the entire West Lake within 130 seconds or so, or saturating the flood storage capacity of the Three Gorges Dam in 2.5 days.

The 1870 flood submerged the pillars of Hall of Yu the Great in the temple

(photo: VCG)

Although it is possible today to cut the flow down to below 80,000 cubic metres per second with the help of numerous reservoirs including Three Gorges Dam, this is still too much for the Jingjiang section.

We need the flood retention and detention basin.

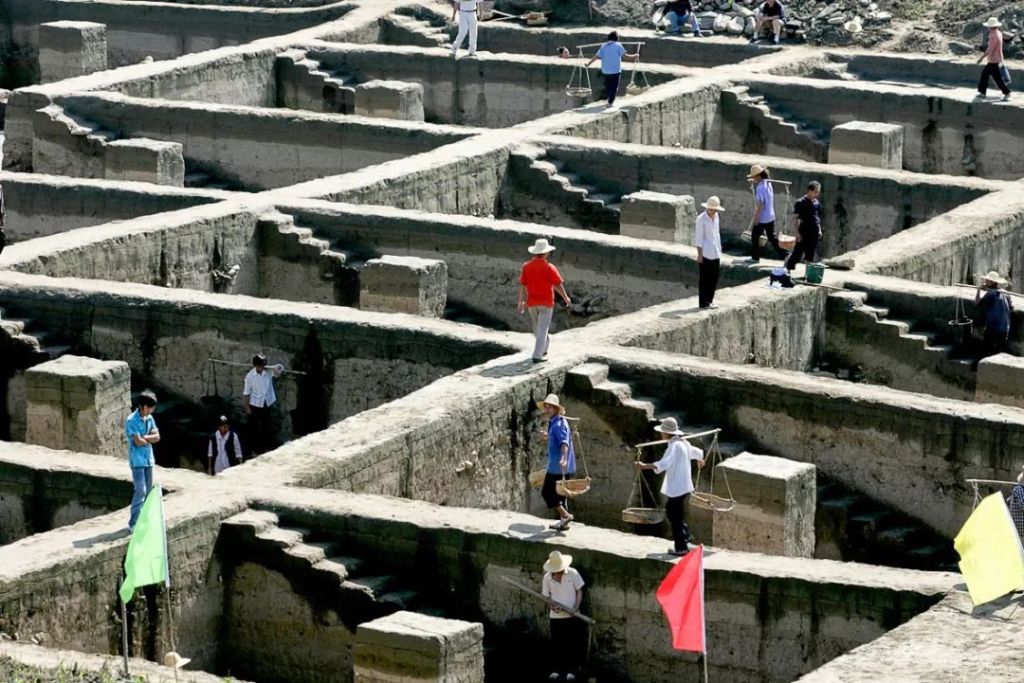

In the spring of 1952, about 300,000 soldiers and civilians spent only 75 days to build the Jingjiang flood retention and detention basin. This basin has an area of 921 square kilometres, which is almost a fourth of that of Poyang Lake, and a flood retention volume of 5.4 billion cubic metres, also a fourth of that of the Three Gorges Reservoir.

Brown line: levee; yellow line: Great Dike of Jingjiang

Crossed box: flood diversion sluice; arrow: flood diversion gate

Basin levee: North flood entry gate (北闸进洪闸), south flood control gate (南闸节制闸), Lijiakou east levee (里甲口东堤), Lalinzhou (腊林洲), Wuliangan (无量庵), Xiaojiazui (肖家咀)

Cities and towns: Jingzhou (荆州), Buhe (埠河), Mishi (弥市), Gongan (公安), Yangjiachang (杨家厂), Jiangling (江陵), Ouchi (藕池), Shishou (石首)

(diagram: 陈志浩 & 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

And it was greeted by the largest flood in the 20th century just two years later in 1954.

It diverted the flood three times in total, thereby successfully lowering the water level in the Jingjiang section and preventing worse outcomes. This was a proof-of-concept experiment on the necessity of a flood retention and detention basin.

Jingzhou is on the opposite bank

(photo: 邓双)

Currently, there are 42 major flood retention and detention basins completed along the midstream of the Yangtze River. With a total area of 12,000 square kilometres, the basins are almost as big as two Shanghai cities combined. The effective storage capacity is 58.97 billion cubic metres, which is comparable to that of the controlled reservoir cluster.

Basins: Jingjiang flood diversion region (荆江分洪区), Gongshuangcha (共双茶), Qianliang Lake (钱粮湖), Dayuan (人民大垸), Hong Lake west, middle & east (洪湖 西·中·东块), Dujiatai (杜家台), Xiliang Lake 西凉湖

Colour (dark to light): Key (重点), important (重要), normal (一般蓄滞洪区) and reserved flood retention and detention basin (蓄滞洪保留区)

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

These basins scatter along the banks of the Yangtze River and around Poyang and Dongting Lakes.

Being the only key flood retention and detention basin, the Jingjiang flood diversion region is absolutely crucial for the safety of the Jingjiang section, and acts as an alarmist for other basins.

And close to the Chen Lake in Wuhan, the Dujiatai basin guards Wuhan, Hanchuan and Xiantao.

This is the flood entry gate of the basin, which had been used for more than 20 times since its completion in 1956

(photo: 尹权)

In addition, all the polders along the midstream and downstream that greatly limited flood-carrying capacity of the river were gradually returned to the lakes since 1998. This restored several billion cubic metres of storage capacity for flood control.

(photo: 荆楚网)

However, these basins always harbour large amount of farmlands, towns and cities. All citizens living there will have to be evacuated prior to flood diversion. And before that, they have to abandon their crops, houses and factories, which will be submerged completely throughout the diversion period.

Therefore, despite the effectiveness of flood retention and detention basins, they are always the very last resort when all hope is lost.

4. The invisible system

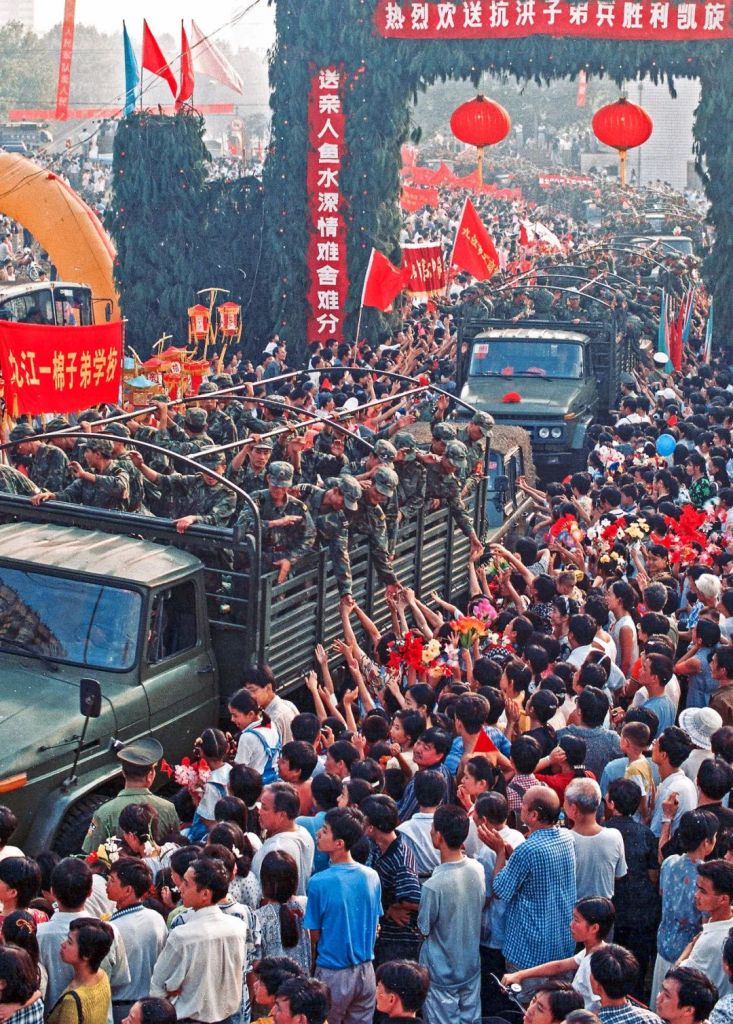

16 August 1998, evening.

More than 300,000 citizens had already been evacuated from the Jingjiang flood diversion basin. Explosives that would blast the levee and let in the flood water were also in place. Everything was ready.

They were just waiting for the flood peak to arrive. A flood peak which no existing flood control measure could ever manage.

This is where flood water will rush in during flood diversion; Jingjiang section is on the far side

(photo: 邓双)

To divert, or not to divert?

If the flood were diverted here, several hundred thousand citizens would become homeless, and their decades of hard work and fortune would turn to dust.

If not, the levee defence line from Jingzhou to Wuhan would burst any time. This would lead to even more catastrophic consequences affecting millions of people.

(photo: VCG)

It was a sleepless night.

The flood diversion area broadcast kept repeating the news about the upcoming diversion, and patrolling inspectors continued to sound the alarm. Soldiers were already stationed at the north flood entry gate awaiting orders, while citizens of the diversion area gazed at their to-be-submerged homes from afar.

After the emergency consultation with an expert panel, the State Flood Control and Drought Relief Headquarters concluded that although the water level of the approaching flood peak would definitely go above the safety line and break all records, calculations indicated that the situation would still be under control as long as the Great Dike of Jingjiang remains standing.

They recommended not to divert the flood.

In the end, ‘People’s Republic did not open the gate (共和国没有开闸).’

Millions of soldiers and civilians defended the Great Dike till their last. Not one levee was breached despite the historical flood peak.

The homes of more than 300,000 citizens were returned to their owners untouched.

(photo: 周国强)

Behind the successful decision is an invisible defence system. It forms the fourth defence line after levees, reservoirs and flood retention and detention basins.

This defence system is a comprehensive surveillance network that is comprised of more than 30,000 hydrological and weather stations, as well as satellites. It monitors and provides real-time feedback on hydrological information that are crucial for flood control decision making.

(photo: VCG)

In addition, an expert panel consisting of fellows from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering, and also technical professionals, analyses the flood and issues forecasts about future development. They are responsible for developing a response plan for flood control.

There is also an administrative system. From the State Flood Control and Drought Relief Headquarters to local grassroots organisations, every entity in the system cooperatively coordinates flood control personnels and supplies, prioritises and implements the response plans.

(photo: 胡寒)

And a frontline that includes soldiers and local civilians, who vigilantly patrol and strengthen the levees, and race against time when flood peaks hit.

(photo: 东部战区微信公众号)

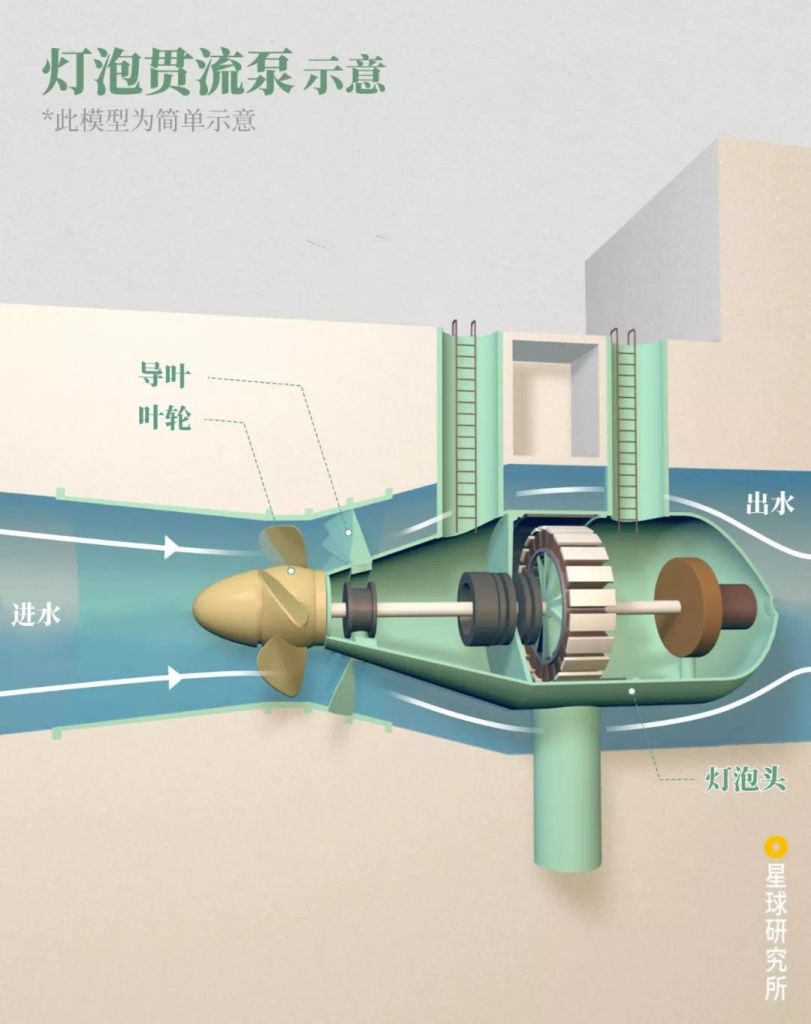

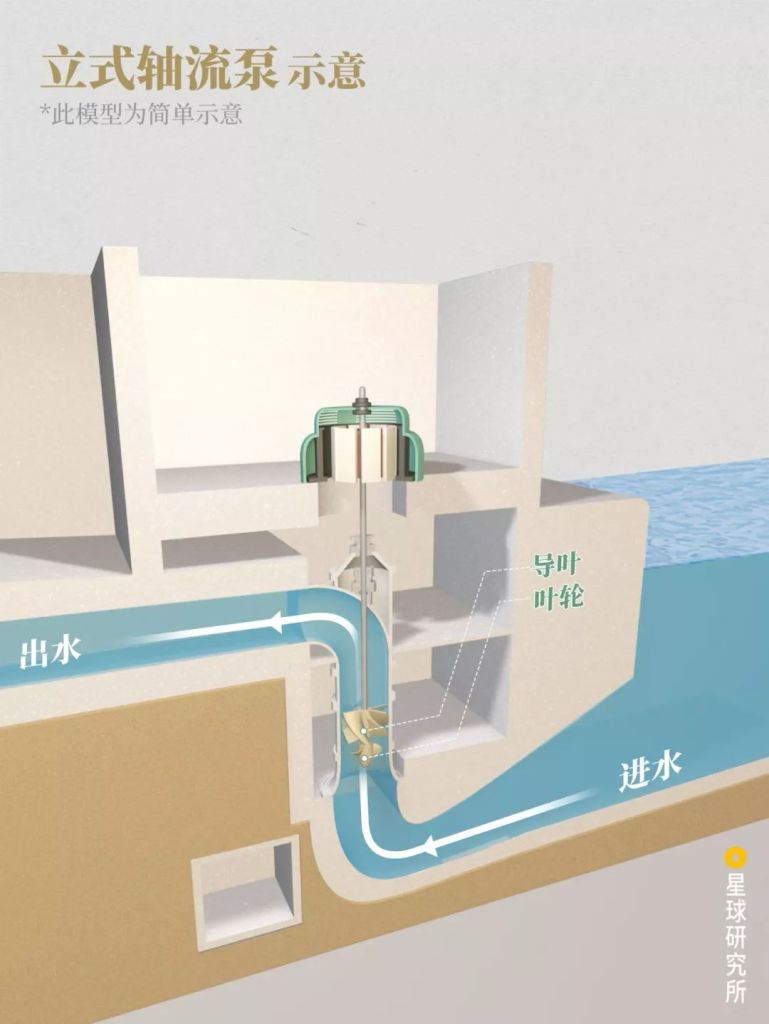

In our flood control defence system, there are long levees that span tens of thousands of miles in total, tens of thousands of reservoirs, dozens of flood retention and detention basins, and numerous gates, stations, channels and pumps along the entire river basin.

It is the invisible defence system that keeps all these running at all times in a coordinated manner.

(photo: 周文军)

Together, these four lines of defence form a safety net that maintains peace along the Yangtze River. It guards 1.8 million square kilometres of land, 500 million people, 40% of China’s GDP and 30% of food production in the country.

Only with these defence lines in place, can we ‘calmly take a leisure walk in the patio despite the roaring winds and charging waves (不管风吹浪打,胜似闲庭信步)‘.

The pavilion on the Huanghuaji in Wuhan was almost completely submerged on 13 July 2020

(photo: 张乔)

Production team

Text: 王朝阳

Photos: 蒋哲睿、谢禹涵

Design: 王申雯、郑伯容

Maps: 陈志浩

Review: 撸书猫、云舞空城

p.s. While writing this piece, Mr Zheng Shouren, a renowned fellow of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and the chief designer of the Three Gorges Dam, passed away in July 2020; we would like to dedicate this piece to all hydraulic engineers and frontline personnels involved in flood control.

References

[1]国家防汛抗旱总指挥部. 长江防御洪水方案(2015)[EB/OL]. 2015.

[2]水利部长江水利委员会. 长江防洪地图集[M]. 科学出版社, 2001.

[3]水利部长江水利委员会. 长江流域蓄滞洪区图集[M]. 科学出版社, 2007.07.

[4]水利部长江水利委员会. 长江重要堤防隐蔽工程地图集[M]. 科学出版社, 2004.09.

[5]汪应国, 李劲松. 惊心动魄: 1998荆江分洪大转移[J]. 当代经济, 1998.

[6]仲志余. 长江防洪[M]. 长江出版社, 2007.

[7]郭铁女, 余启辉. 长江防洪体系与总体布局规划研究[J]. 人民长江, 2013.

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光