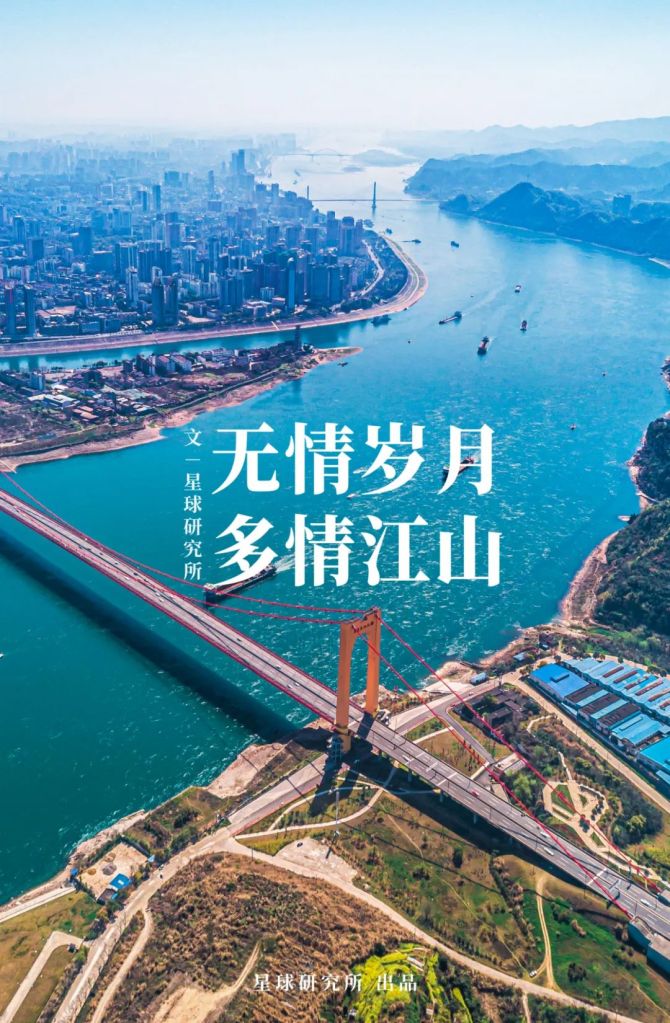

Original piece: 《什么是黄河?》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 风子

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

The surging power of a surging nation

Most people have heard of the Yellow River of China, but few truly know its brilliance.

The river travels across vast distance. Close to its origin, Yellow River is a clear and gentle stream.

(photo: 陈二狗的摩旅)

In the midstream, the giant river courses through breathtaking sceneries.

(photo: 许兆超)

As it charges on, it leaves behind a serpentine trail in the downstream.

(photo: 吴亦丹)

Yellow River is a perennial witness of time.

It observed all changes in the landscape throughout the last 3.7 million years.

(photo: 李珩)

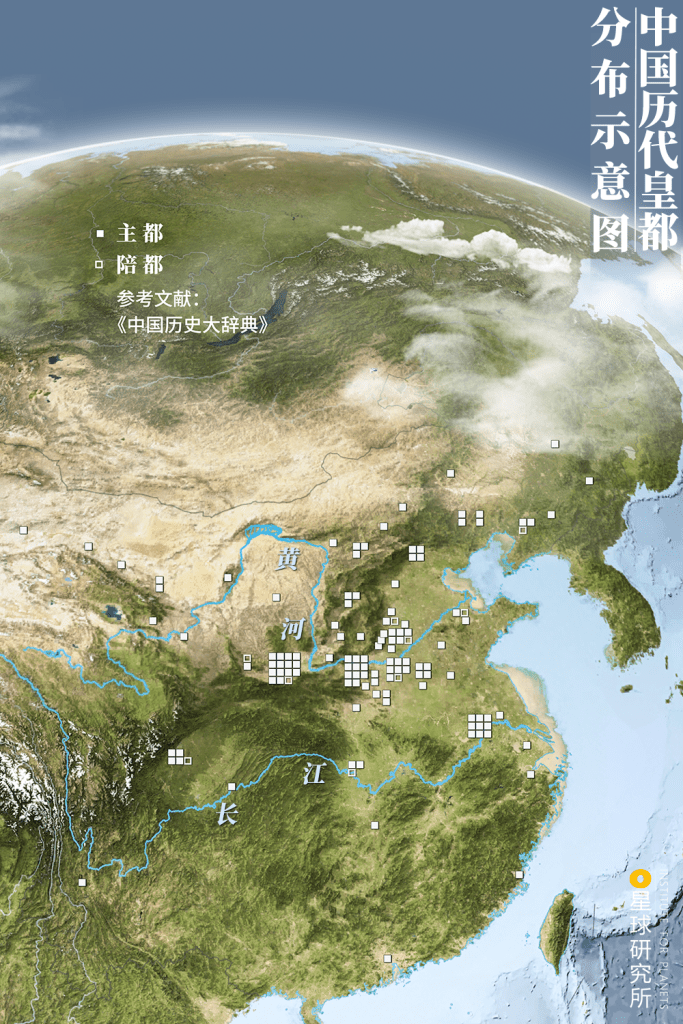

And saw the rise of a grand civilisation that spanned five millennia.

(photo: 李琼)

To the Chinese people, it is the spiritual stronghold that holds the nation together in its most dire moments.

The wind is howling, the horses screaming

And the Yellow River roaring

……

Defend our homeland!

Defend the Yellow River!

Defend the Northern Plains!

Defend our country!风在吼,马在叫

Yellow River Cantana (7th movement: Defend the Yellow River) by Guang Weiran

黄河在咆哮

……

保卫家乡!保卫黄河!

保卫华北!保卫全中国!

《黄河大合唱》第七乐章《保卫黄河》– 光未然

What gives Yellow River its unmatched brilliance?

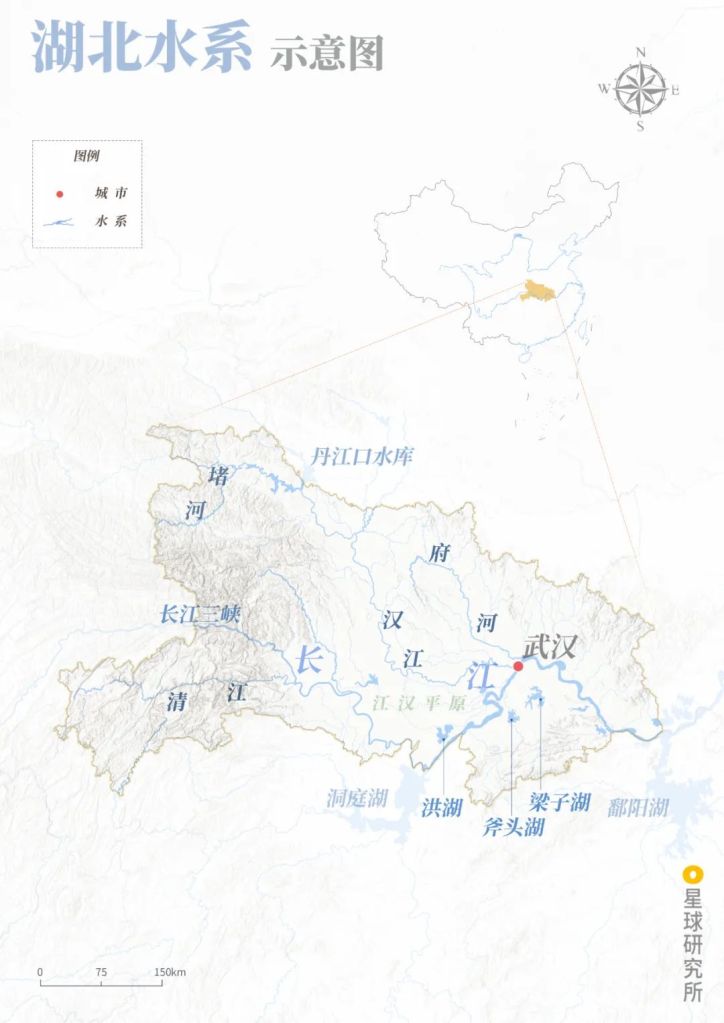

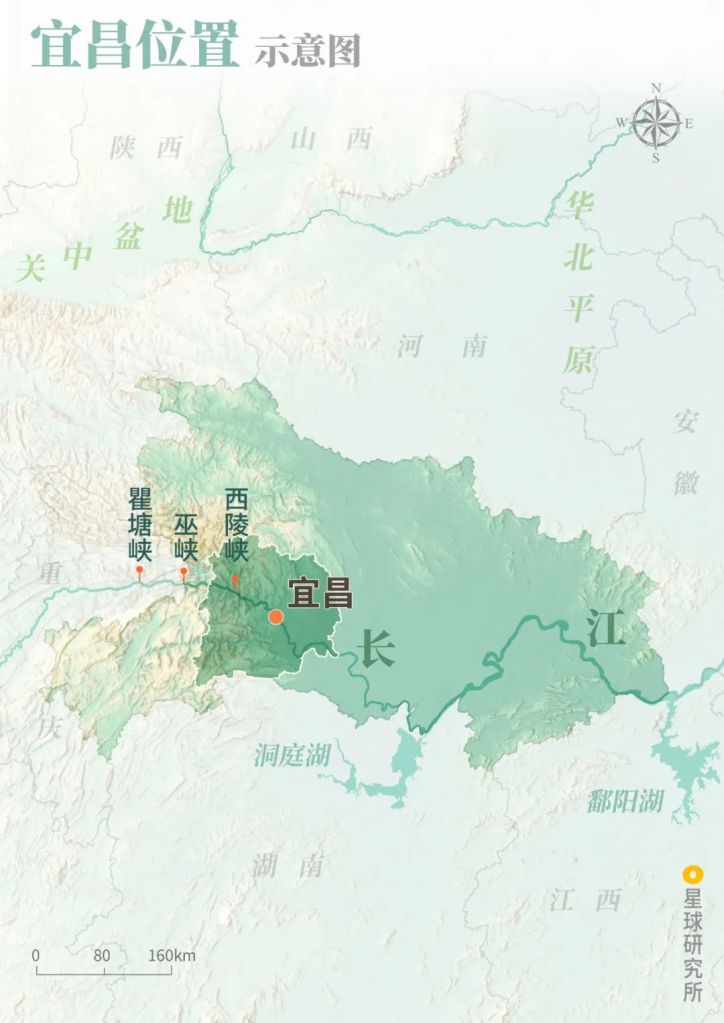

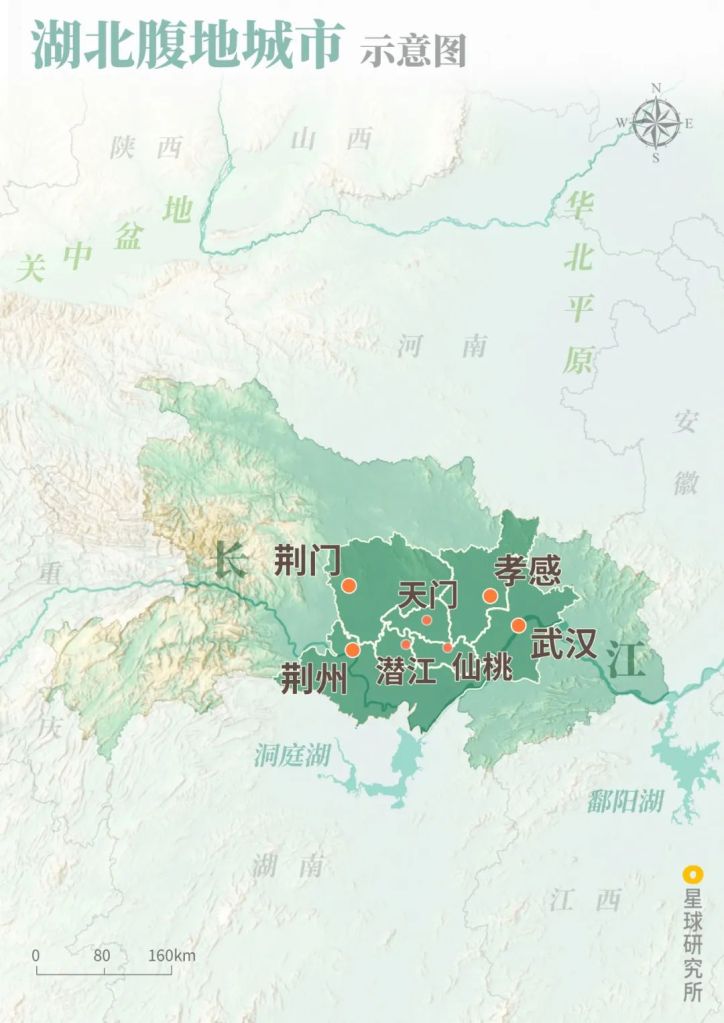

The Institute for Planets sees it as a strong bond that strings up the Chinese civilisation in time and space. Being the second longest river in China, it overcomes all barriers and runs entwined with all on its way to the sea. And in doing so, it shapes a nation that is always surging with vibrance.

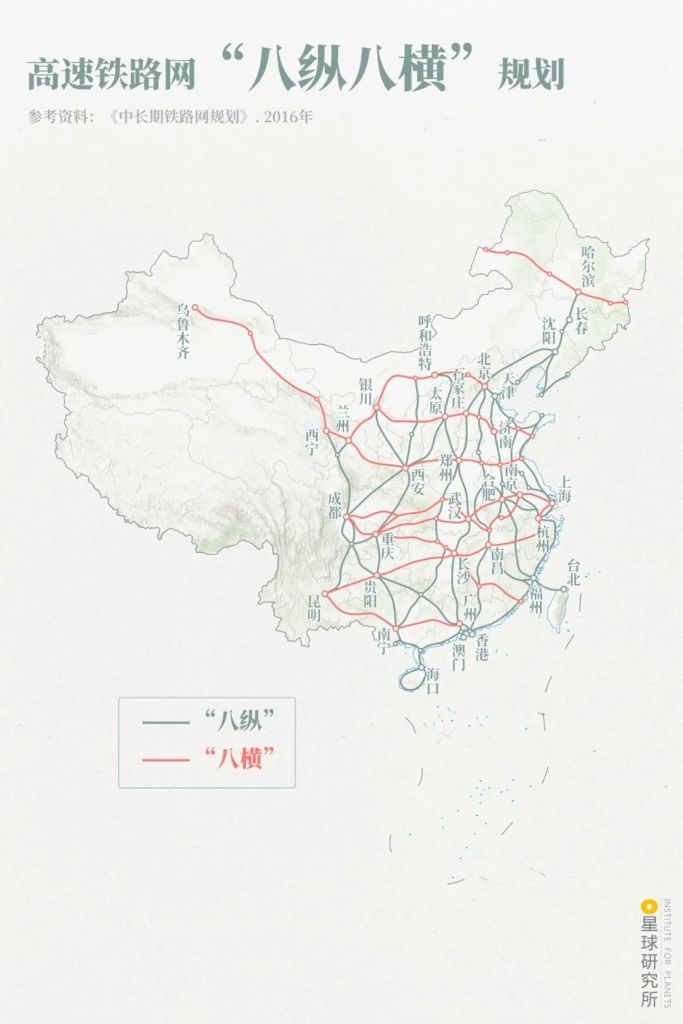

1. The traverse

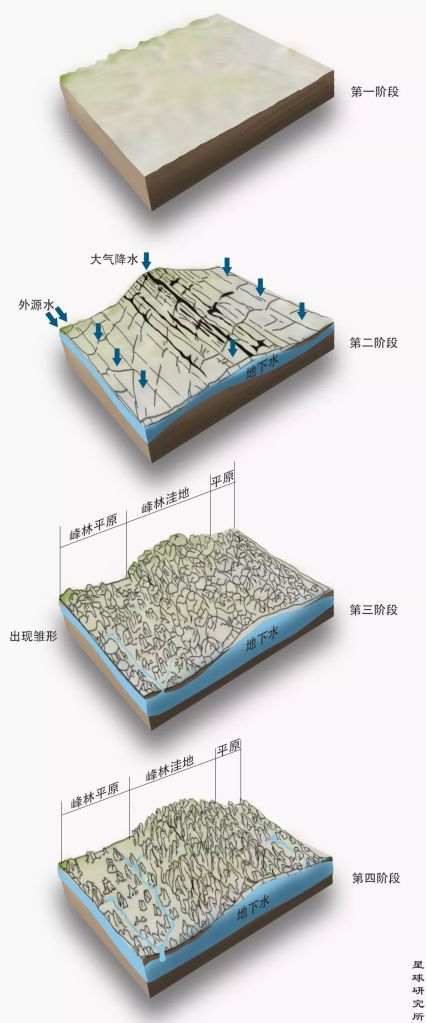

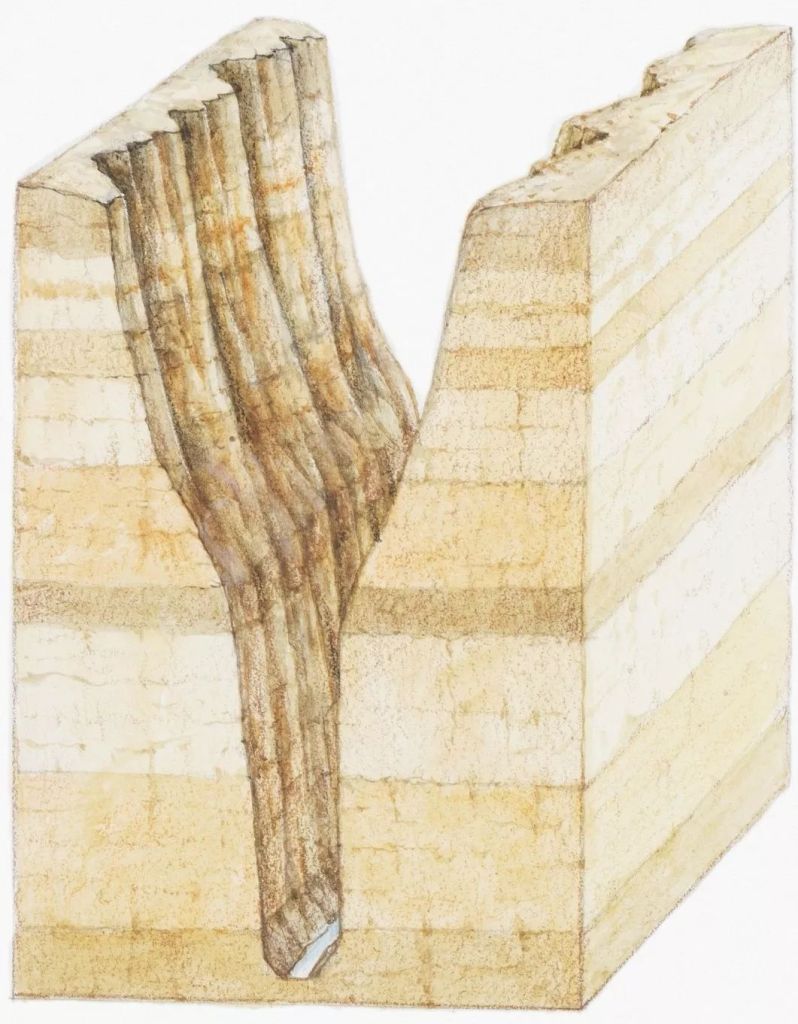

Over the last 65 million years, tectonic collision between the Indian Plate and the Eurasian Plate had created a unique topography in China where the west is much more elevated than the east. It also led to deformation of the inland which, together with movements of the Pacific Plate, ruptured the North China Plain. A series of rift valleys and basins were hence formed sequentially.

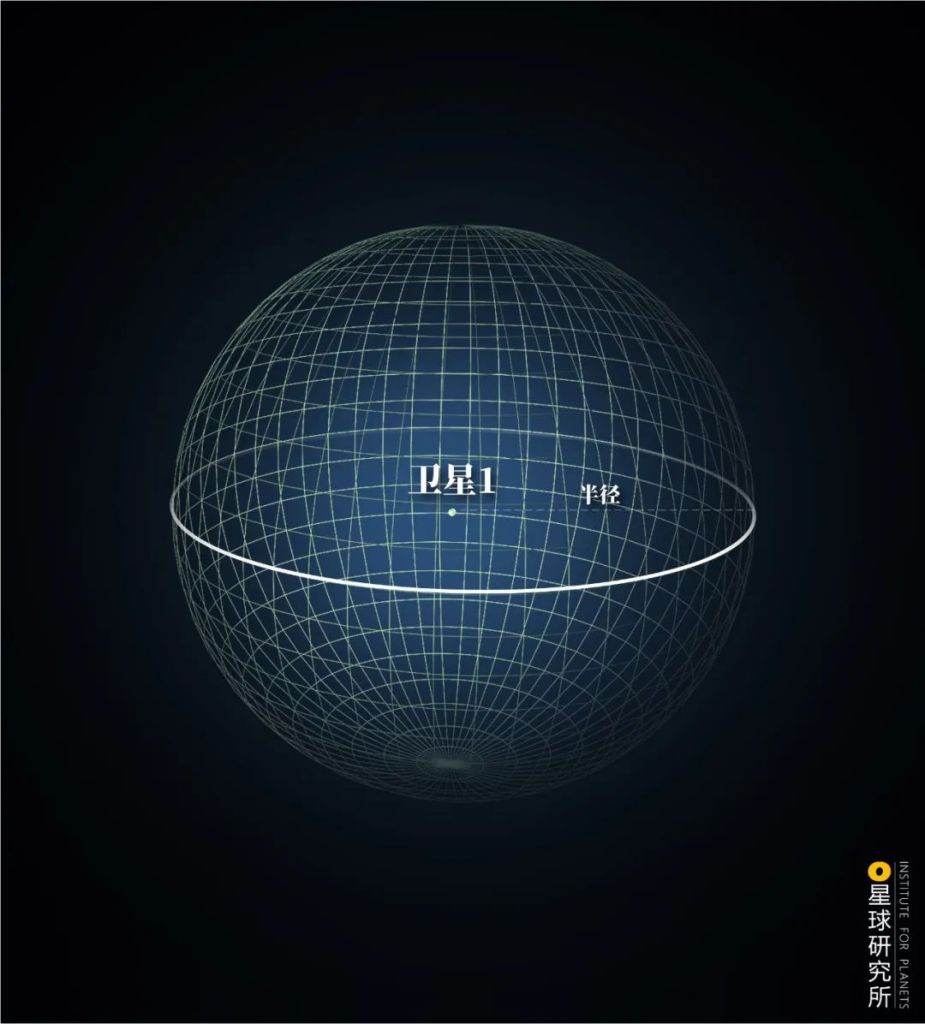

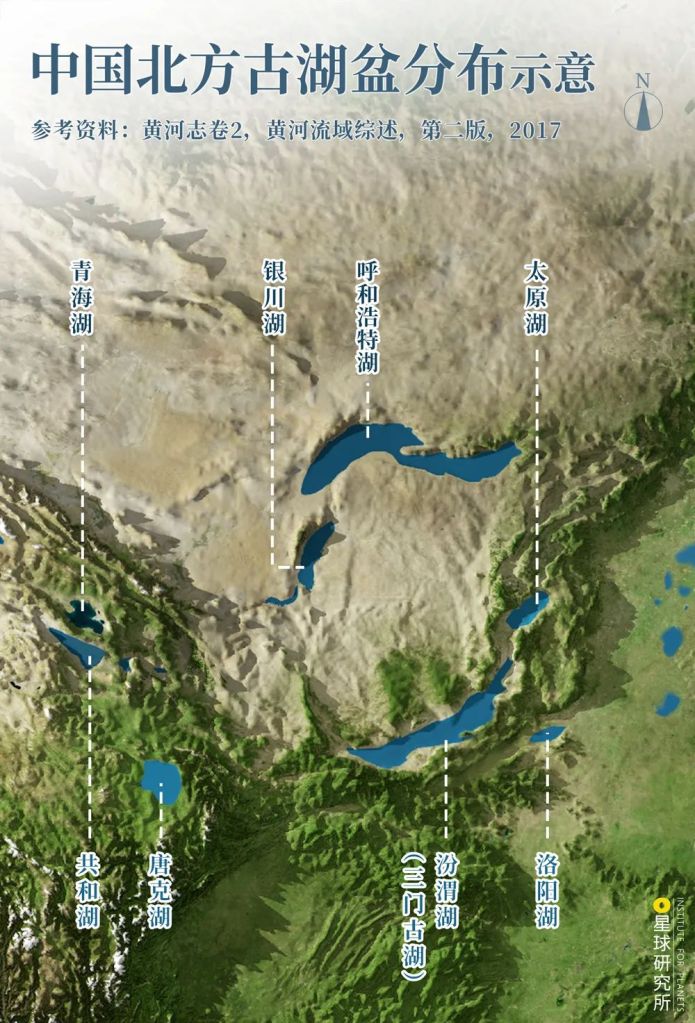

Fast forward to 3.7 million years ago, each of these depressions had by then gathered sufficient water to become lakes of various sizes, which were relatively dispersed and lacked any form of connection. At this stage, the Yellow River was still no where to be seen.

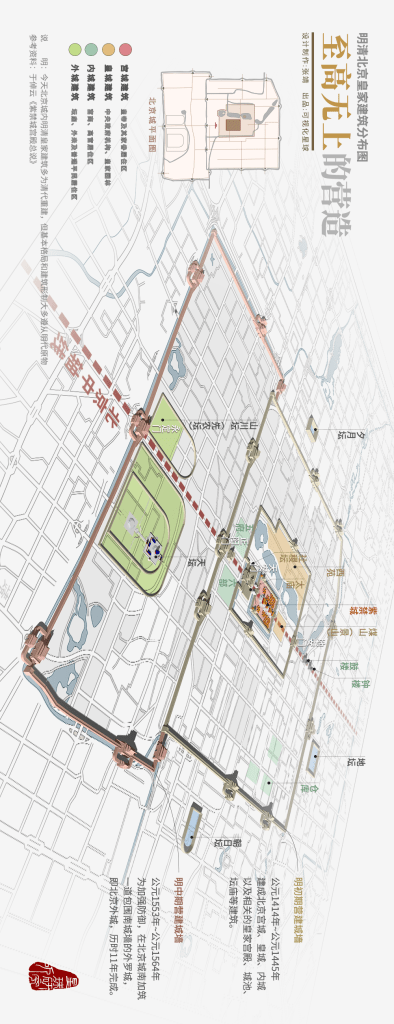

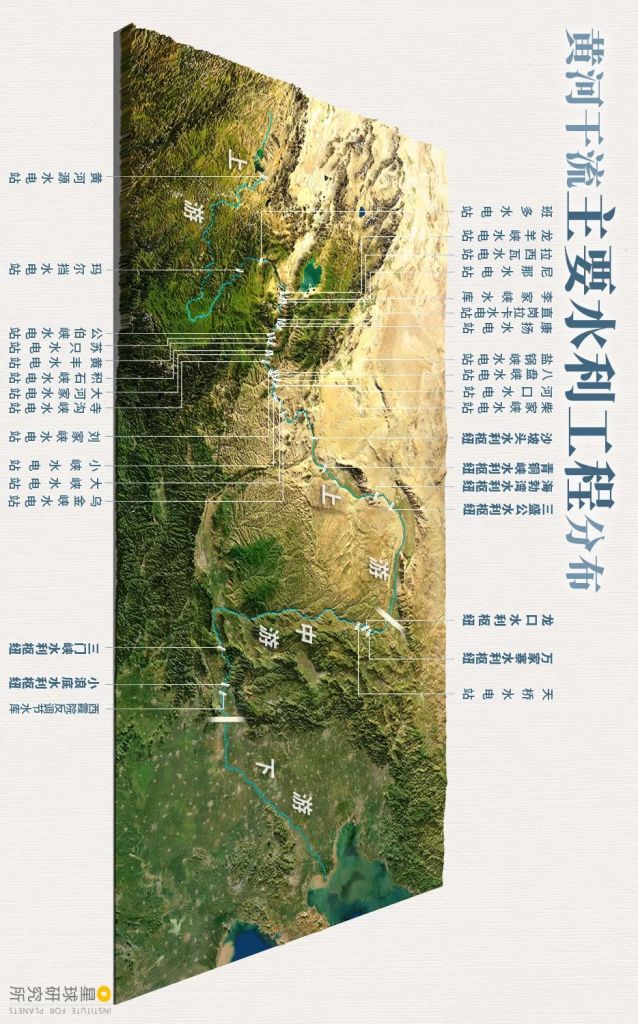

Nomenclature of ancient basins may vary among different sources

Qinghai Paleolake (青海湖), Yinchuan Paleolake (银川湖), Hohhot Paleolake (呼和浩特湖), Taiyuan Paleolake (太原湖), Gonghe Paleolake (共和湖), Tangke Paleolake (唐克湖), Fenwei Paleolake (汾渭湖; Sanmen Paleolake, 三门古湖), Luoyang Paleolake (洛阳湖)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

As tectonic movements persisted, the Tibetan Plateau and Loess Plateau kept rising higher. This natural process continued to enlarge the elevation difference between the west and east, much like a divine force holding an enormous pot of water high up in the sky and still lifting it further.

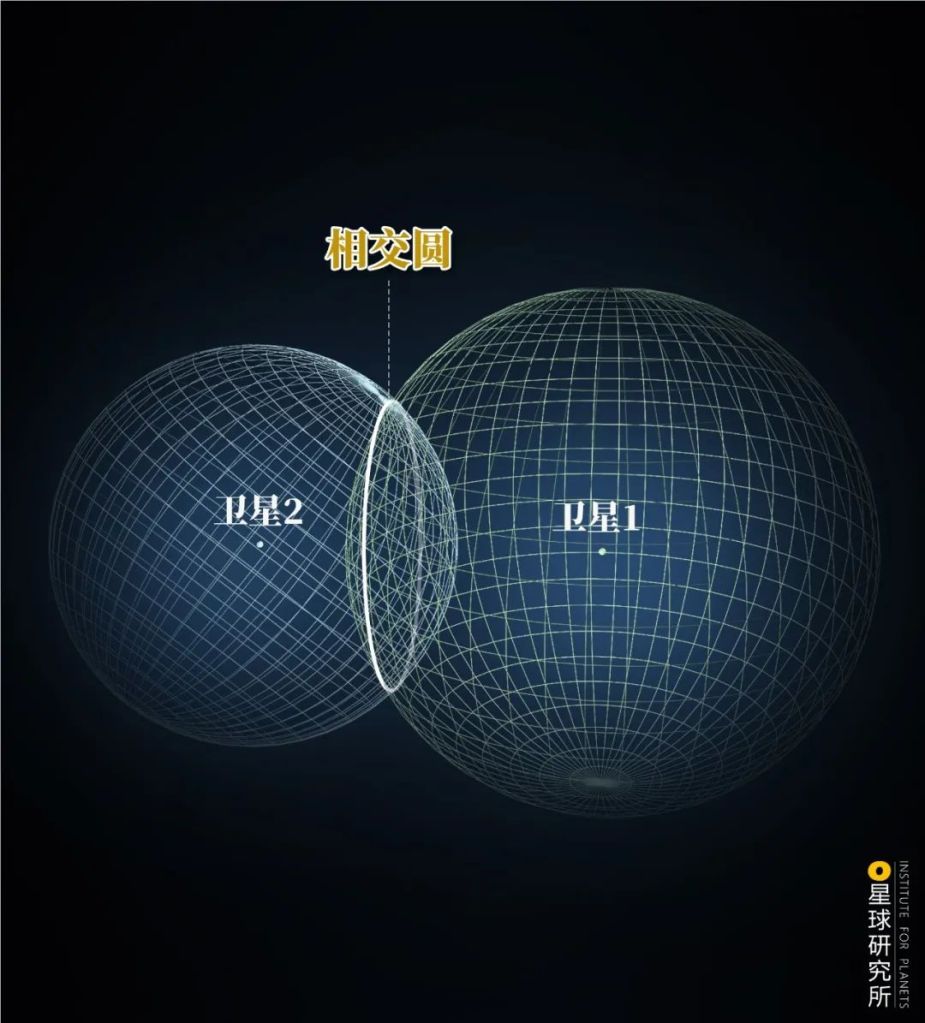

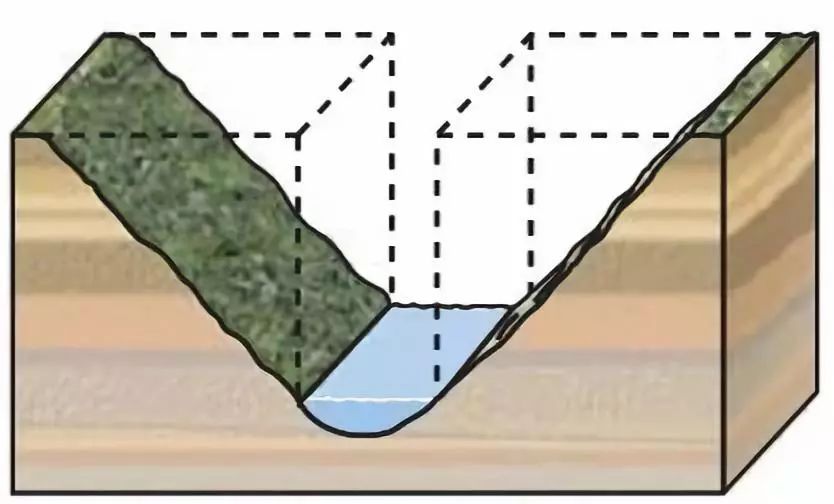

As a consequence, the previously disconnected lake systems started to invade into each other’s territories down the slopes. This initiated a series of lake and river concatenation on a massive scale on North China Plain.

By about 1.8 million years ago, the river channel between Lanzhou and Hetao (literally ‘river loop’) was the very first section to take form on the western stretches of Loess Plateau.

(photo: 王生晖)

Water systems merged together by this included the Lanzhou Basin, Zhongwei Basin, Yinchuan Basin and Hetao Basin.

(photo: 陈剑峰)

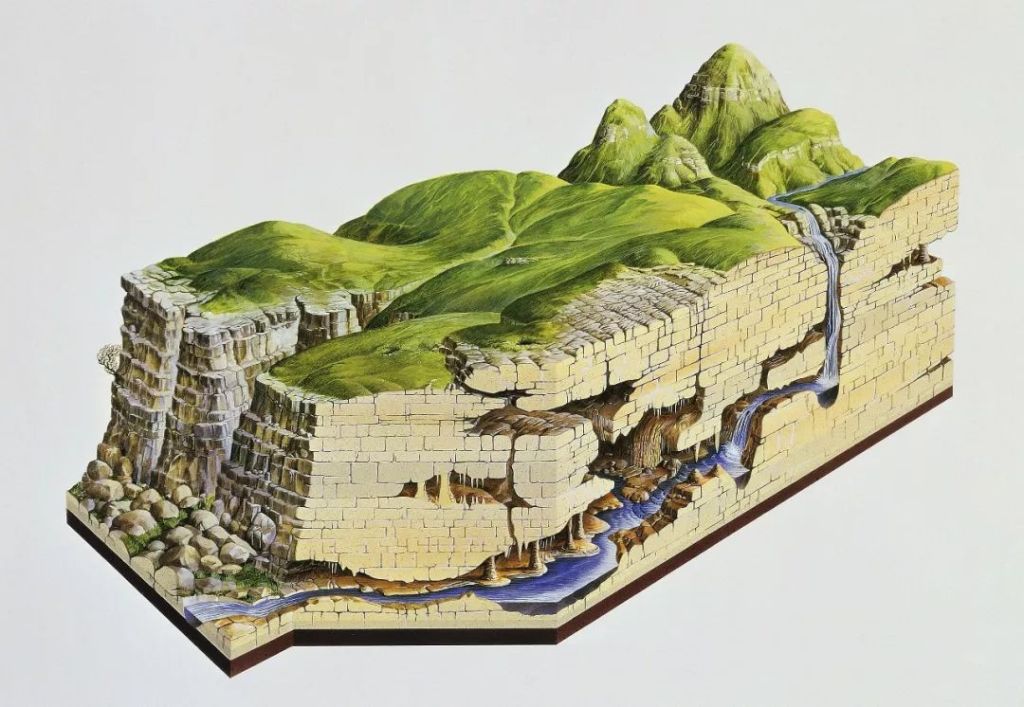

There were numerous gorges engraved along the way, including the Bapan Gorge, Chaijia Gorge, Sangyuan Gorge, Wujin Gorge, Hongshan Gorge, Heishan Gorge, Hu Gorge and Qingtong Gorge.

(photo: 王生晖)

In Central China, rivers running across the northern regions of Fenwei Basin carved out a northbound path over time through the Loess Plateau, which eventually met up with the Hetao Basin around 1.2 million years ago. This formed the Shanxi-Shaanxi section we see today that demarcates the two provinces.

Stretching from Togtoh County of Inner Mongolia in the north and Yumenkou of Shanxi in the south, the section has a total length of 725 kilometres

(photo: 陈肖)

Happening simultaneously was the westward invasion of rivers flowing by the eastern foothills of Taiheng Mountains. Approximately 1.2 million years ago, one of these rivers finally penetrated the Xiao Mountains and carved out the Sanmen Gorge, thereby making a way out of the Fenwei Basin into the North China Plain.

This is the last gorge in the midstream of Yellow River

(photo: 邓国晖)

This breach allowed the vast paleolake to gush down the heights through the Sanmen Gorge and embark on a one way journey to the east.

Loess Plateau (黄土高原), North China plains (华北平原)

Sanmen Paleolake (三门古湖), Sanmen Gorge (三门峡)

(diagram: 王申雯&陈景逸, Institute for Planets)

As such, a new river that first traverses the Loess Plateau and North China Plain then dashes towards the sea in the far east was officially born. This was the Yellow River in its adolescence.

(photo: 赵斌)

The young river was still rather short, spanning only about 60% of the current length. Moreover, the upstream travelled mainly through dry areas in the northwest, where water source was relatively scarce.

(photo: 陈剑峰)

Therefore, it was still far from becoming what we know of the Yellow River — a majestic river with impressive length and turbulent waters. What it needed was to extend further away from the sea and climb even higher up the mountains.

2. The expansion

Approximately 1.2 million years ago, the Amne Machin (also known as Mount Jishi) standing between Xunhua Basin in Qinghai and Linxia Basin in Gansu was cut open by Yellow River. This opened up a new route for the upstream flowing across Linxia Basin, which then changed course and entered the Tibetan Plateau through Jishi Gorge.

(photo: 王生晖)

Once on the loose, Yellow River met almost no resistance as it raged across the Tibetan Plateau, carving out a chain of gorges including the Songba Gorge, Ashgang Gorge, Longyang Gorge, Lagan Gorge, Yehu Gorge and Lajia Gorge.

(photo: 孙建鑫)

As it progressed, it linked up Guide Basin, Gonghe Basin, Xinghai-Tongde Basin and Zoige Basin.

(photo: 孙建鑫)

But it was not until about 10,000 years ago when Yellow River finally cut through the Duoshi Gorge did the Gyaring Lake-Ngoring Lake systems become incorporated into the grand river.

(photo: 仇梦晗)

That marked the completion of modern Yellow River system.

Yellow River have had multiple diversions in the lower course in recorded history, shown here are the current river channels

Plateau/plains: Tibetan Plateau (青藏高原), Loess Plateau (黄土高原), North China Plain (华北平原)

Basins: Zoige Basin (若尔盖盆地), Zhongwei Basin (中卫盆地), Yinchuan Basin (银川盆地), Weihe Basin (渭河盆地), Houtao Basin (后套盆地), Fenhe Basin (汾河盆地), Qiantao Basin (前套盆地), Luoyang Basin (洛阳盆地)

Gorges: Duoshi Gorge (多石峡), Longyang Gorge (龙羊峡), Jishi Gorge (积石峡), Liujia Gorge (刘家峡), Qingtong Gorge (青铜峡), Sanmen Gorge (三门峡), Shanxi-Shaanxi Grand Canyon (晋陕大峡谷)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

Through diversion and expansion that lasted more than 1.2 million years, Yellow River not only extended its length by almost 2000 kilometres…

(photo: 蒋晨明)

But also acquired a number tributaries in the upstream for replenishment, including Qiemuqu, Hei River, Bai River and Jiaqu.

(photo: 李威男)

All these water sources upstream of Jishi Gorge contribute up to around 40% of the entire basin volume. If tributaries further downstream are included, particularly Huangshui River and Tao River which also originate from Tibetan Plateau, the sections up to Lanzhou would make up for 61.7% of the total runoff of Yellow River.

(photo: 李俊博)

The Tibetan Plateau, standing on average 4000 metres above sea level, has clearly become the predominant drainage basin for Yellow River.

As Li Bai, the renowned poet of Tang Dynasty, once exclaimed:

(Do you not see) the Yellow River coming down from the sky,

Rushing to the sea and never come back?(君不见)

Invitation to Wine by Li Bai (Translation by Li Yuanchong)

黄河之水天上来

奔流到海不复回?

《将进酒》李白 (李渊冲 翻译)

This is where Yellow River makes the first big turn around the mountain ranges; the majority of meltwater from Amne Machin flows into Yellow River

(photo: 行影不离)

As Yellow River expanded, it gained more power to reshape the land. It transformed the Shanxi-Shaanxi river channel into Shanxi-Shaanxi Grand Canyon.

(photo: 许兆超)

With constant erosion, the Hukou Waterfall slowly retreated away from Yumenkou, leaving behind the ‘Ten-mile Dragon Trough (十里龙槽)’ that exhibits a valley-within-valley terrain.

Hukou Waterfall has retreated by around 5 kilometres from the Mengmen Mountain over the past several thousand years, leaving behind the Ten-mile Dragon Trough, a river terrace which has now become a popular tourist spot

(photo: 李顺武)

More importantly, formation of Yellow River basin and the coinciding climate changes have gradually drained a number of ancient lakes and marshes, which were initially connected to the basin through various tributaries. The discharge at Zoige Paleolake had turned it into Zoige Wetland.

(photo: 熊可)

The Sanmen Paleolake in Fenwei Basin is pretty much nonexistent today. Whatever remained had evolved into the Yuncheng Salt Lake…

(photo: 赵高翔)

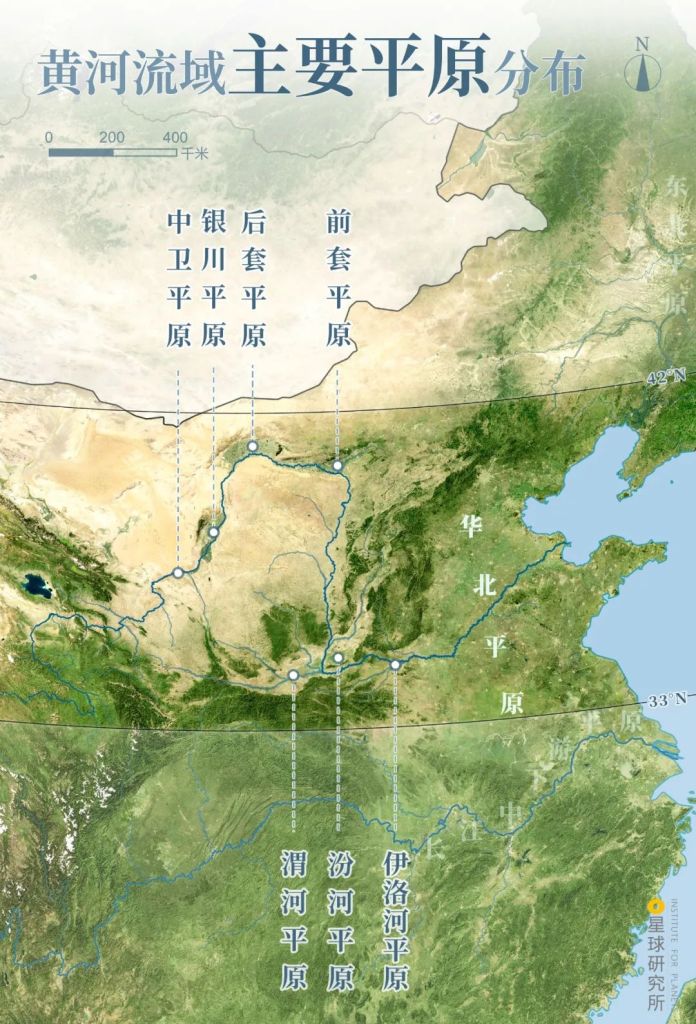

And various alluvial plains, including Zhongwei Plain, Yinchuan Plain, Hetao Plain, Weihe Plain and Fenhe Plain.

(photo: 魏炜)

In the meantime, silt coming from the upstream had further flattened the North China Plain.

(photo: 视觉中国)

In a way, Yellow River managed to stitch all the largest alluvial plains in China together.

Zhongwei Plain (中卫平原), Yinchuan Plain (银川平原), Houtao Plain (后套平原), Qiantao Plain (前套平原), Weihe Plain (渭河平原), Fenhe Plain (汾河平原), Yiluohe Plain (伊洛河平原)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

Since all these plains were mostly located in warm climate zones, they provided perfect conditions for societal development in the age of agriculture.

Everything was set for the coming to be of a grand civilisation.

3. The civilisation

The first cultures to emerge along the Yellow River basin were scattered around the midstream, dotting the Weihe Plain, Fenhe Plain, Liluohe Plain, Taiheng Mountains and eastern foothills of Mount Song.

Agriculture developed rapidly here as the climate was warm and humid, and the land was very fertile and easy to farm. To maintain a stable food source, our ancestors domesticated several crops that did not require excessive attention, including foxtail millet and broomcorn millet. This guaranteed the basic needs for the survival of a population.

Millets are now replaced with wheat

(photo: 射虎)

And to have a ceiling, caves and crypts were extensively built on loess-covered terraces.

(photo: 王警)

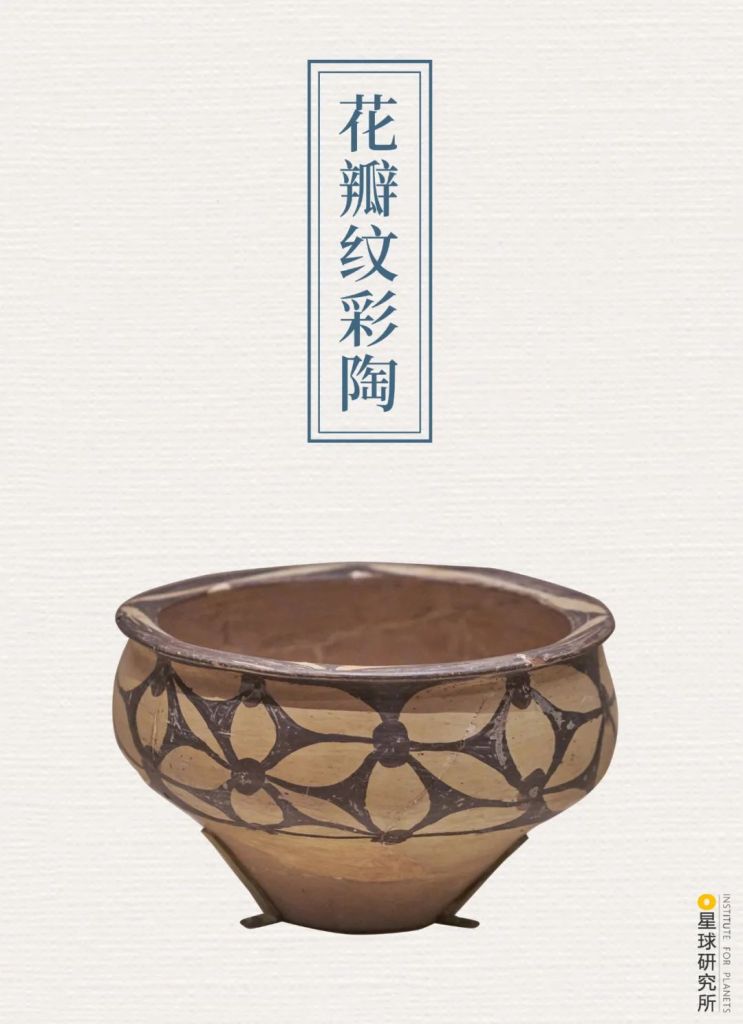

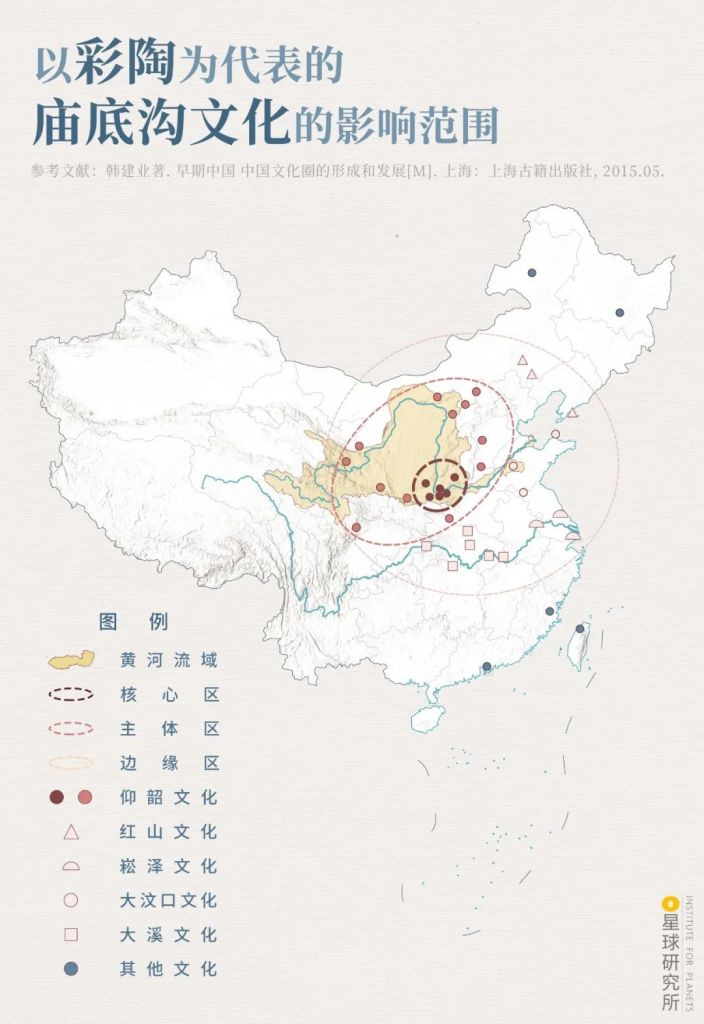

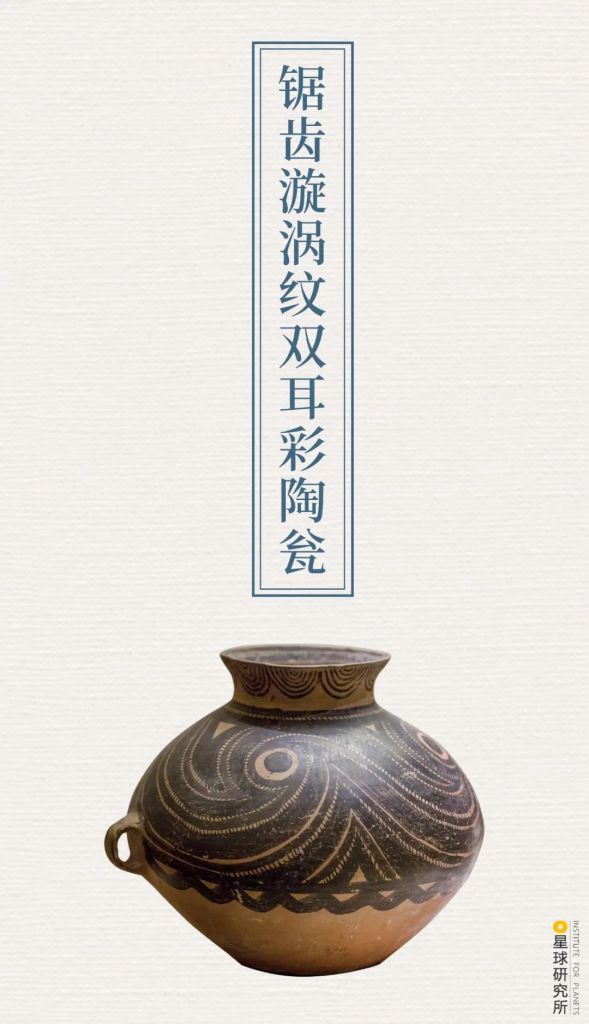

When all the basic needs were met, our ancestors turned to leisure and art. By the middle phase of Yangshao culture (~4000-3500 BC), Miaodigou settlers living near Sanmen Gorge had already had the skills to produce burnished potteries adorned with red and black paint that ran in artistic geometry patterns with rhythmic sensations. These products were apparently very popular back then.

(photo: 汇图网)

Their influence on painted pottery design reached as far as Qinghai in the west, East China Sea in the east, Yangtze River basin in the south and Mongolian-Liaoning regions in the north. The radiating charm of Miaodigou culture is said to have facilitated the very first cultural integration in prehistoric China.

Yellow River basin (黄河流域)

Core region (核心区), main region (主体区), peripheral region (边缘区)

Yangshao culture (仰韶文化), Hongshan culture (红山文化), Songze culture (崧泽文化), Dawenkou culture (大汶口文化), Daxi culture (大溪文化), others (其他文化)

(diagram: 王申雯&陈景逸, Institute for Planets)

But as the population continued to grow, competition exacerbated and the pressure on survival became real. Around the midstream, population density was the highest in Guanzhong, Jinnan and Yuxi regions. To fight for resources, heavily armed citadels were built and wars were fought.

This archaeological site sits on a terrace located to the south of the intersection of Luo River and Yellow River (黄河).

It was a city-scale central settlement 5300 years ago; experts have suggested to name it the Ancient Kingdom of Heluo.

(photo: 石耀臣)

Others who did not want to be involved dispersed into surrounding regions. One group which travelled to the west along Wei River entered the Ganqing region in the Yellow River upstream. There they merged with local ethnic groups and became the Majiayao culture. These people not only inherited the essence of Miaodigou’s painted pottery production, but went further and perfected the craftsmanship. Almost all their unearthed potteries were brightly coloured with smooth linings and complex embellishments. They had obviously outshined their predecessors in pottery production.

(photo: 杨虎)

Another settlement that moved northwards along Shanxi-Shaanxi Yellow River made contact with indigenous people of Hetao region, who were distributed in the southern foothills of Yin Mountain-Daqing Mountain ranges.

There are numerous ruins distributed around the southern foothills of Daqing Mountain

(photo: 陈剑峰)

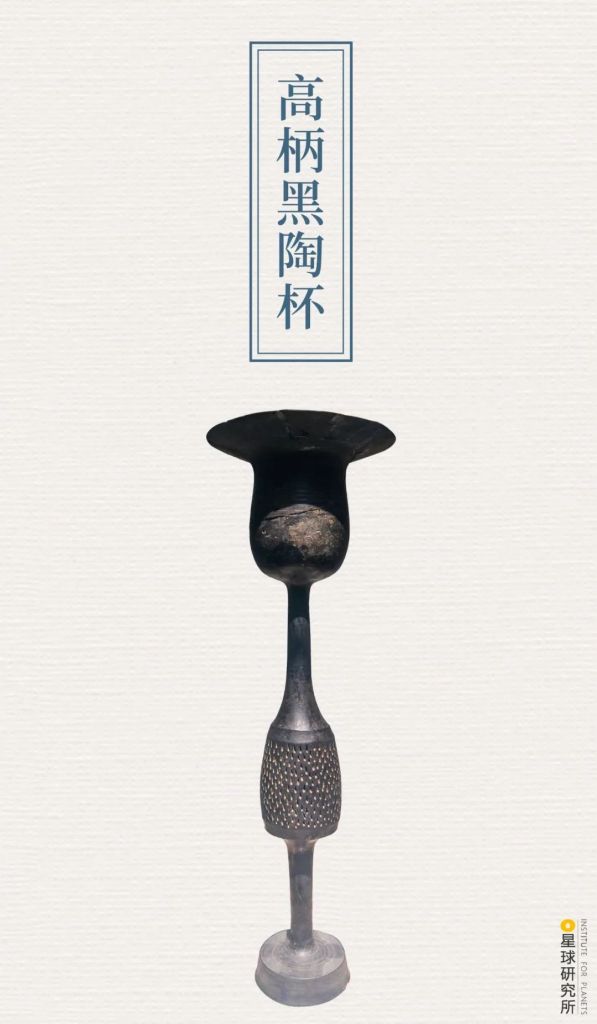

In downstream regions of Yellow River, the people of Dawenkou culture were leading equally well-off lives near the Tai-Yi Mountains. They were very open to Yangshao culture from the west and Hongshan culture from the north, and eventually evolved into the famous Longshan culture. The black pottery long-handle goblet was a very well known artefact unearthed in the Chengziya ruins in Zhangqiu, Jinan. With a bowl thickness of an egg shell, the goblet is widely regarded as a modern creation, if not better.

(photo: 翟东润)

By integrating surrounding cultures, settlements in the Yellow River midstream nurtured a new school of thoughts by around 2500 BC. People living there started observing astronomical phenomena and seasonal changes in order to improve farming efficiency.

Comprised of 13 rammed earth columns erected in a semicircle configuration, this is the oldest observatory ruins ever discovered; shown in photo is a restoration of the observatory

Observers could identify the sunrise position at Ta’er Mountain through the gaps between the columns, thereby deducing the season and solar terms to guide farming activities

(photo: 视觉中国)

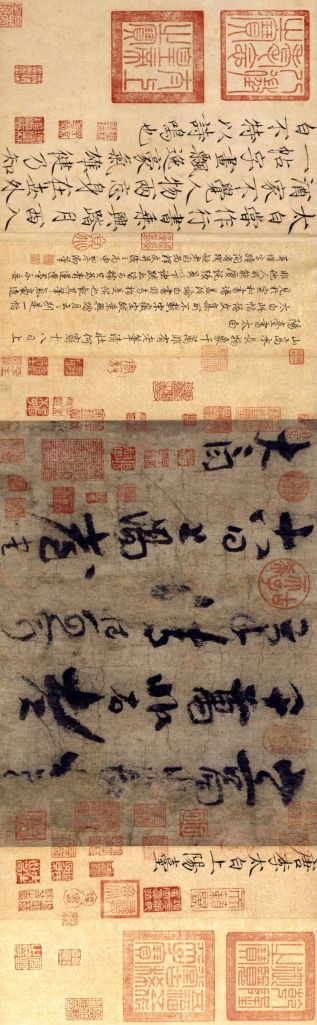

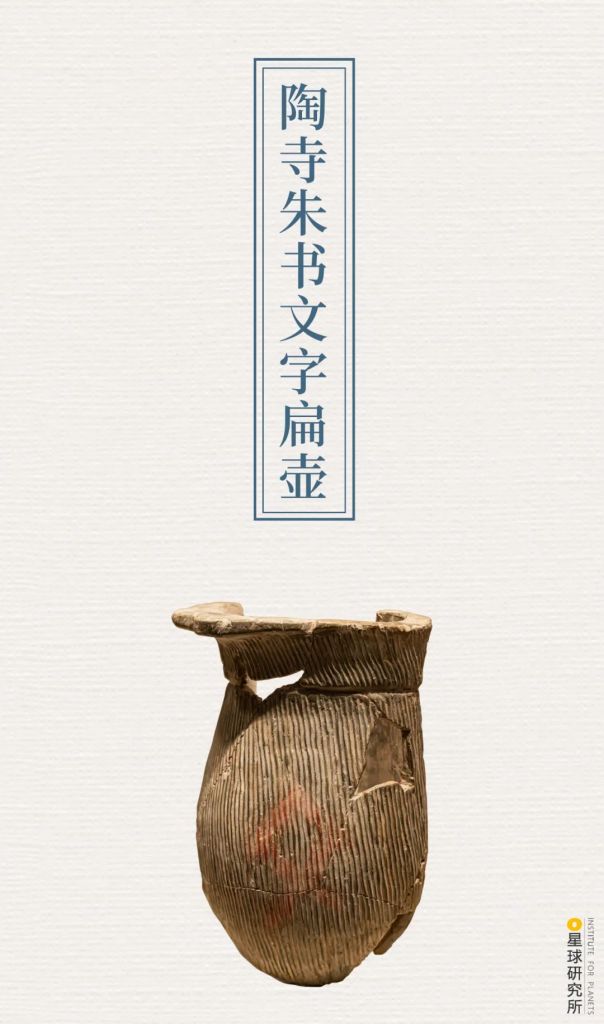

They even created a primitive form of writings that were similar to the later oracle bone scripts we all know about.

The word on the pottery is currently translated as “文”

(photo: 王宁)

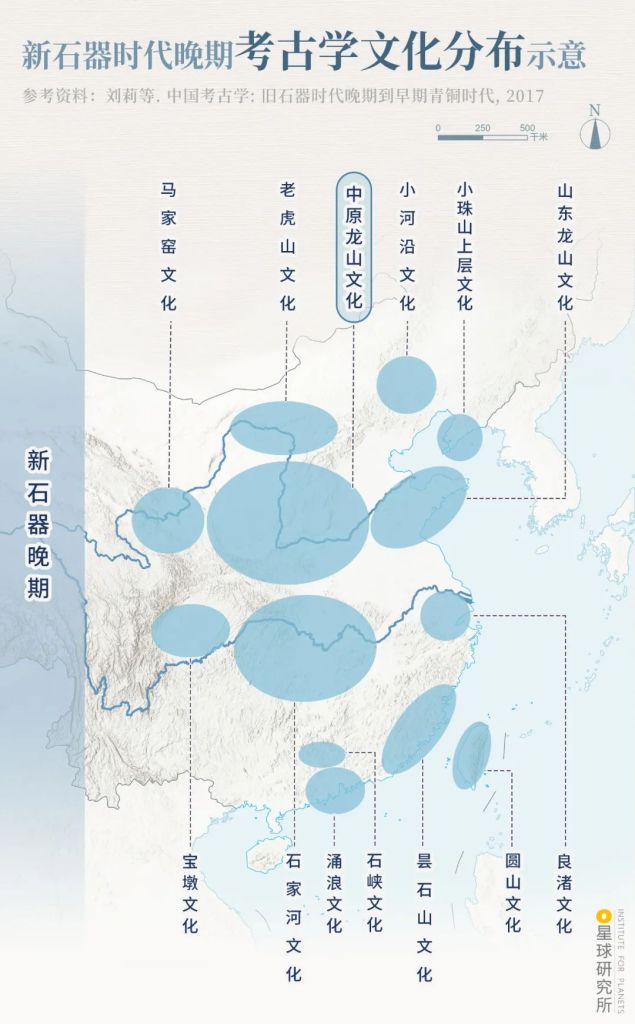

It is generally accepted that various ancient cultures along the Yellow River basin made the first entry into early phases of civilisations in around 3300-2000 BC. Also rising during the same period were the Liangzhu culture and Shijiahe culture emerging in the downstream and midstream of Yangtze River respectively, as well as the Baodun culture settling on the Chengdu Plain. These cultures were as advanced as those around the Yellow River basin.

(photo: 苏李欢)

Ancient civilisations were enjoying their first spring then as they blossomed all over China.

Majiayao culture (马家窑文化), Laohushan culture (老虎山文化), Central Plain Longshan culture (中原龙山文化), Xiaoheyan culture (小河沿文化), Upper Xiaozhushan culture (小珠山上层文化), Shandong Longshan culture (山东龙山文化), Baodun culture (宝墩文化), Shijiahe culture (石家河文化), Yonglang culture (涌浪文化), Shixia culture (石峡文化), Tanshishan culture (昙石山文化), Yuanshan culture (圆山文化), Liangzhu culture (良渚文化)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

So what made the cultures along Yellow River basin stand out from the rest?

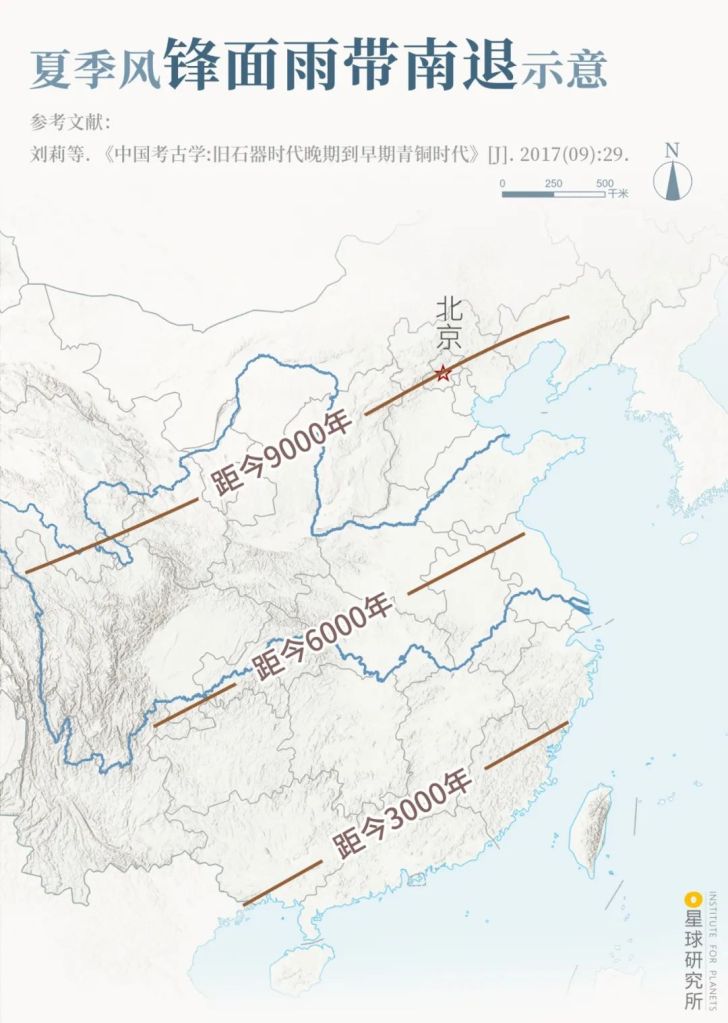

Between 2200-2000 BC, there was a global cooling event. In addition to a sharp temperature drop, summer monsoons were significantly weakened and rainbands at the monsoon front retreated to the south. While northeast and northwest regions suffered from severe droughts, North China and Jiangnan regions were hit by increased rainfalls and floods.

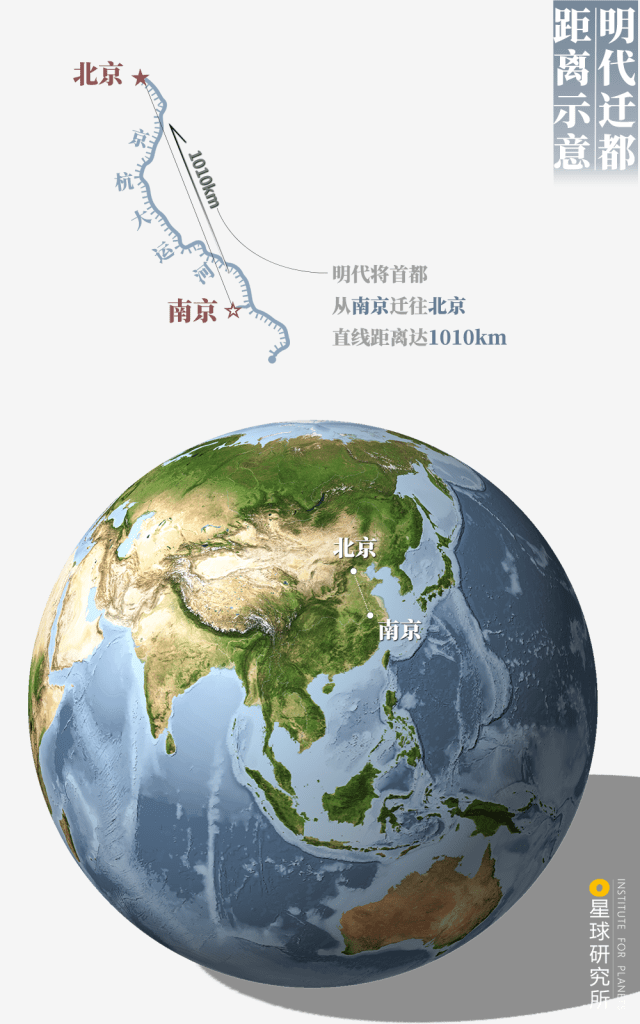

Beijing (北京), n years ago (距今 n 年)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

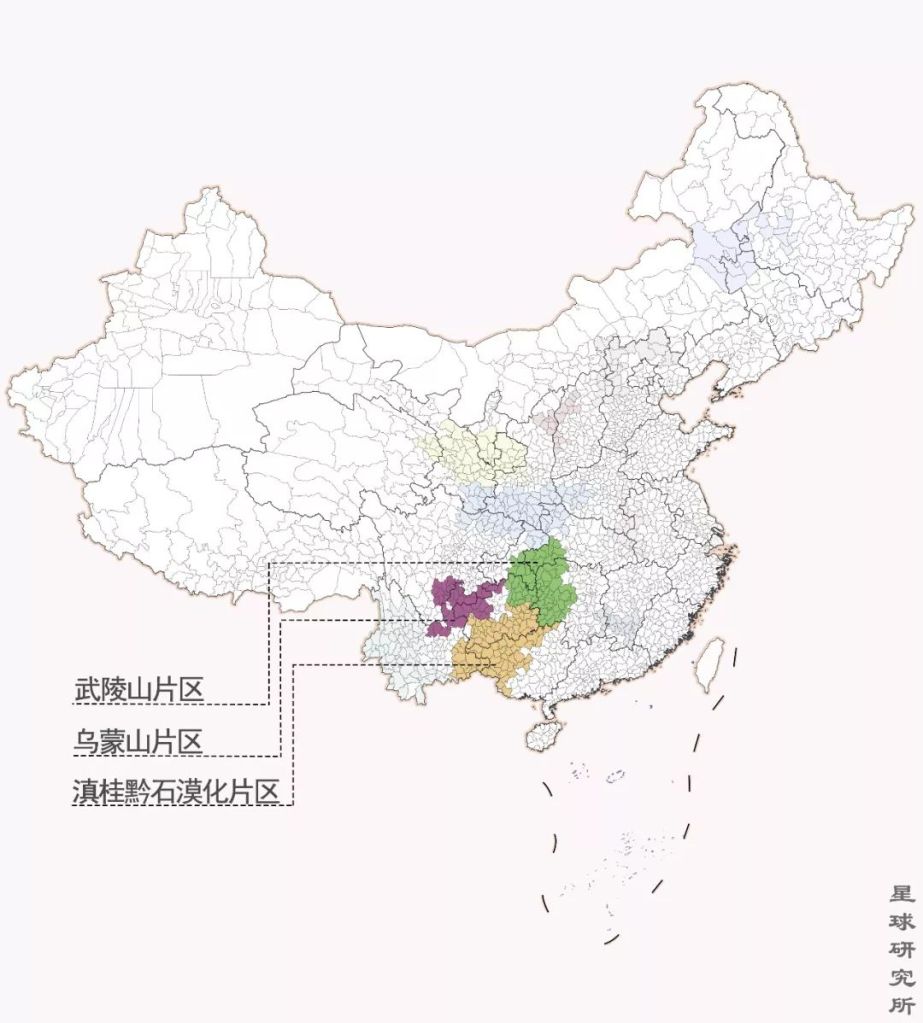

Because of that, Laohushan culture in Inner Mongolia, Qijia culture in Gansu-Qinghai regions, as well as Liangzhu culture, Shijiahe culture, Shandong Longshan culture along Yangtze River all fell victim to either life-threatening droughts or deadly floods. They never made it further.

On the contrary, cultures residing in Guanzhong-Jinnan-Yuxi regions in the midstream of Yellow River seized the chance to become the centre of civilisation. Survival of the fittest seemed to have settled the fierce competition on this great arena and decided on the few rising stars of Chinese civilisation.

*The impact of climate change on the decline of numerous cultures 4000 years ago was first proposed by renowned archaeologist Su Bingqi. The decline could also be impacted by many other factors, including demography, society, economy and religion.

Late Neolithic Age (新石器晚期): see above diagram

Erlitou Age (二里头时期): Qijia culture (齐家文化), Zhukaigou culture (朱开沟文化), Datuotou culture (大坨头文化), Lower Xiajiadian culture (夏家店下层文化), Gaotaishan culture (高台山文化), Miaohoushan culture (庙后山文化), Yueshi culture (岳石文化), Sanxingdui culture (三星堆文化), Guangshe culture (光社文化), Erlitou culture (二里头文化), Xiaqiyuan culture (下七垣文化), Doujitai culture (斗鸡台文化), Lower Dianjiangtai culture (点将台下层文化), Maqiao culture (马桥文化)

(diagram: 王申雯&陈景逸, Institute for Planets)

How did they survive?

One reason was that the midstream of Yellow River was sitting right in the centre of China, therefore it was not as dry as northwest and Inner Mongolian regions, yet did not have to deal with the horrible floods as did its southern neighbours.

More importantly, there was extensive formation of foothill elevation and alluvial fans along the Yellow River, which acted as a Noah’s Ark that always floated above water level. Also crucial were the drainage systems that prevented serious damages to the settlements. Civilisation was thus well preserved.

(photo: 焦潇翔)

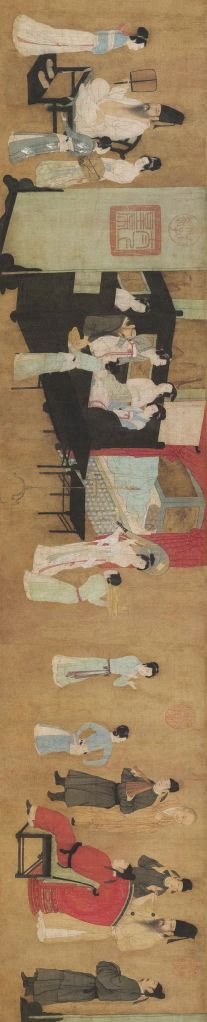

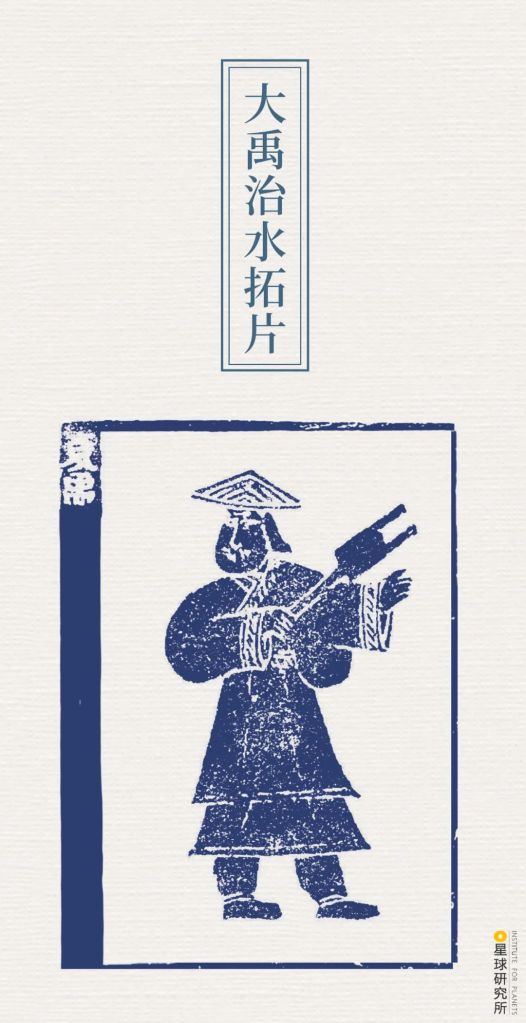

This was where Yu the Great assembled his legendary flood control team, which swiftly restored regional safety and agricultural activities. This catalysed the birth of a kingdom with widespread territory control in the midstream of Yellow River, which was later named Xia — the very first dynasty in Chinese history.

This Eastern Han artefact was unearthed in Shandong

With that as a foothold, our ancestors began to spread out into even larger alluvial plains, which provided ample space and resources for development. The Chinese civilisation finally gained traction and started to display its power.

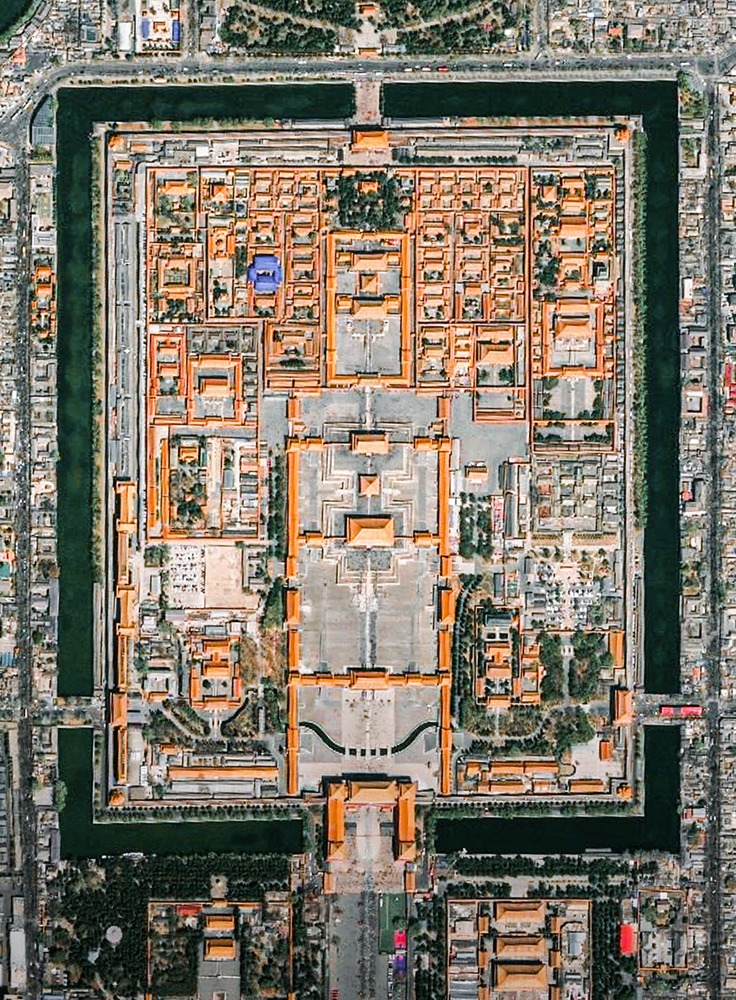

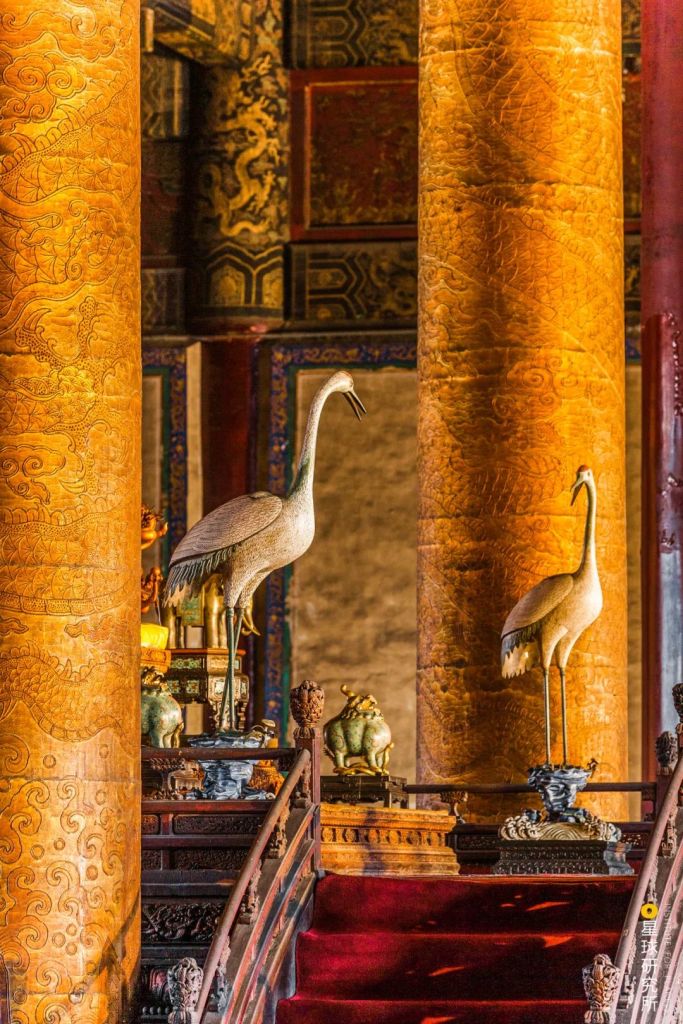

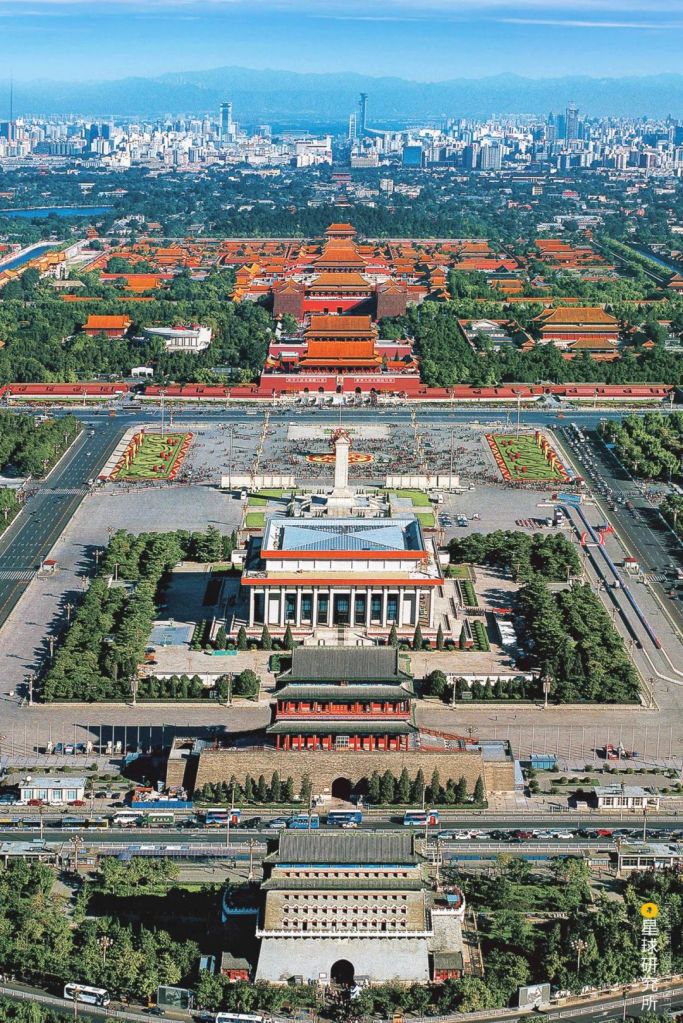

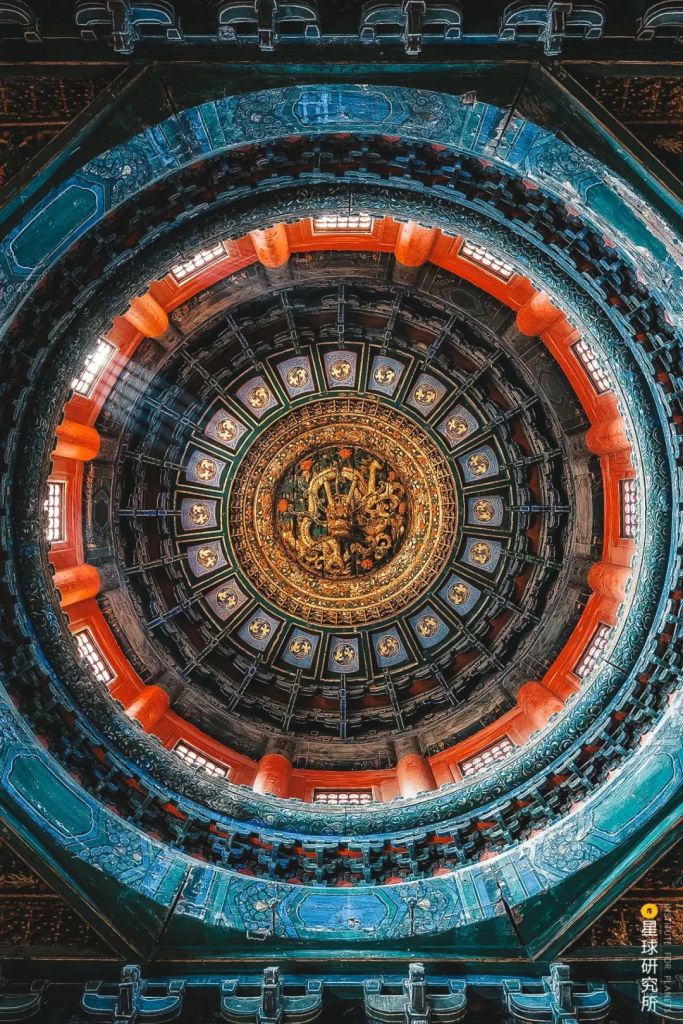

It built grand palaces.

Shown in the photo is the modern Luo River (洛河); prior to Eastern Han Dynasty, Luo River used south of the ruins.

Palace site 1, 2 (一,二号宫殿), palace wall (宫墙)

(photo: 丁俊豪)

And massive cities.

Spanning 13 million square metres, this city was believed to be one of the earliest capitals of Shang Dynasty

Photo shows the inner city wall

(photo: 石耀臣)

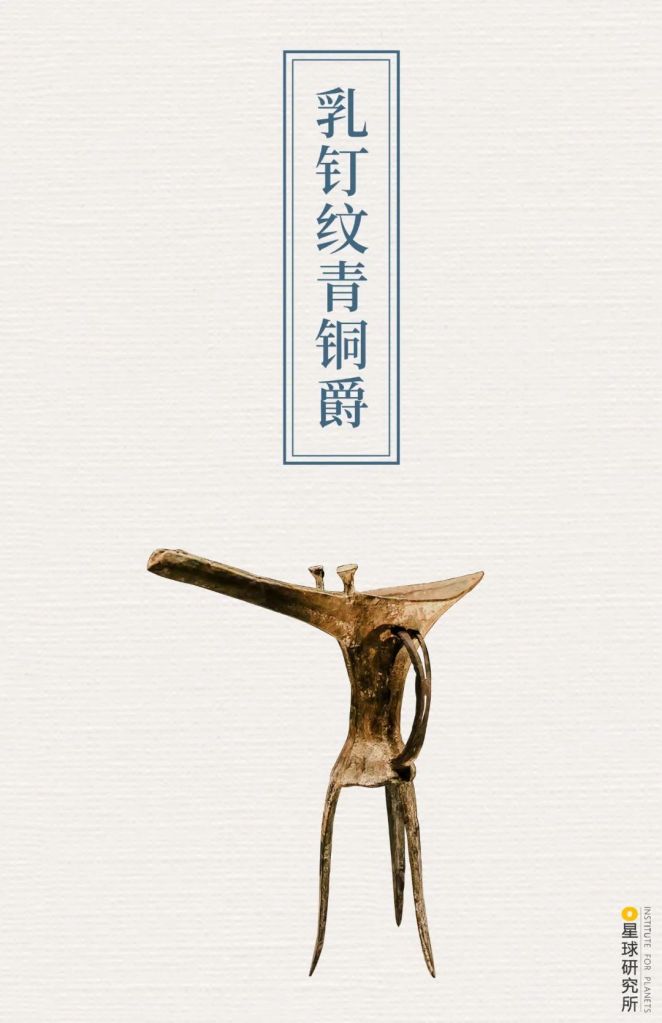

It welcomed talents, and adopted different technologies and cultures. One after another, groundbreaking advancements were made. There was bronze smelting.

Unearthed in Erlitou ruins, this jue is the oldest bronze wine vessel discovered in China.

(photo: 李文博)

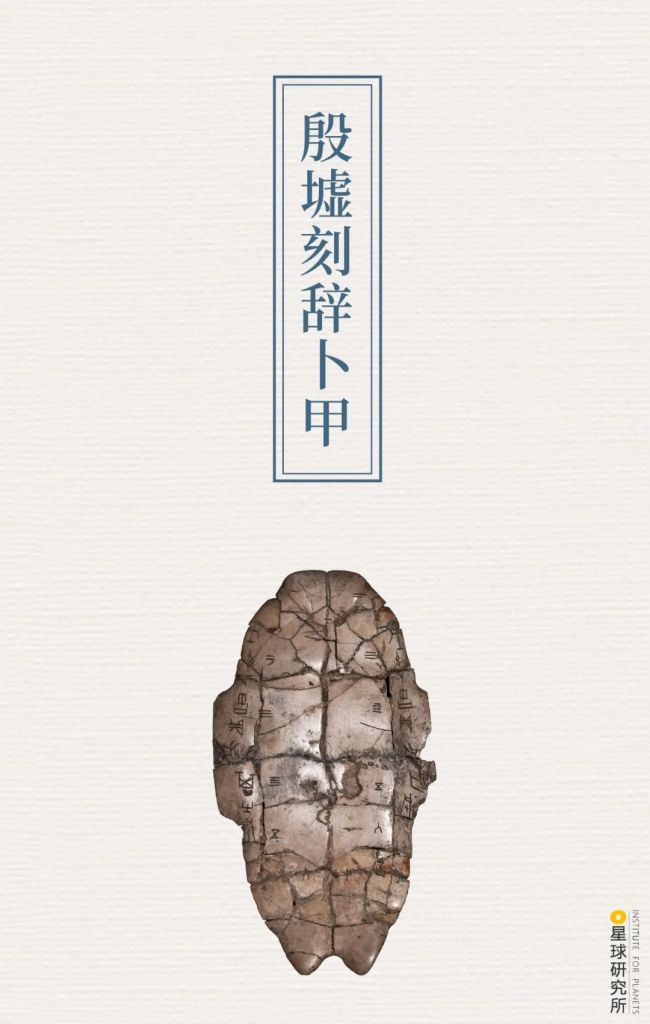

Writing.

Oracle bone inscriptions are the earliest known writing system in China

(photo: 柳叶氘)

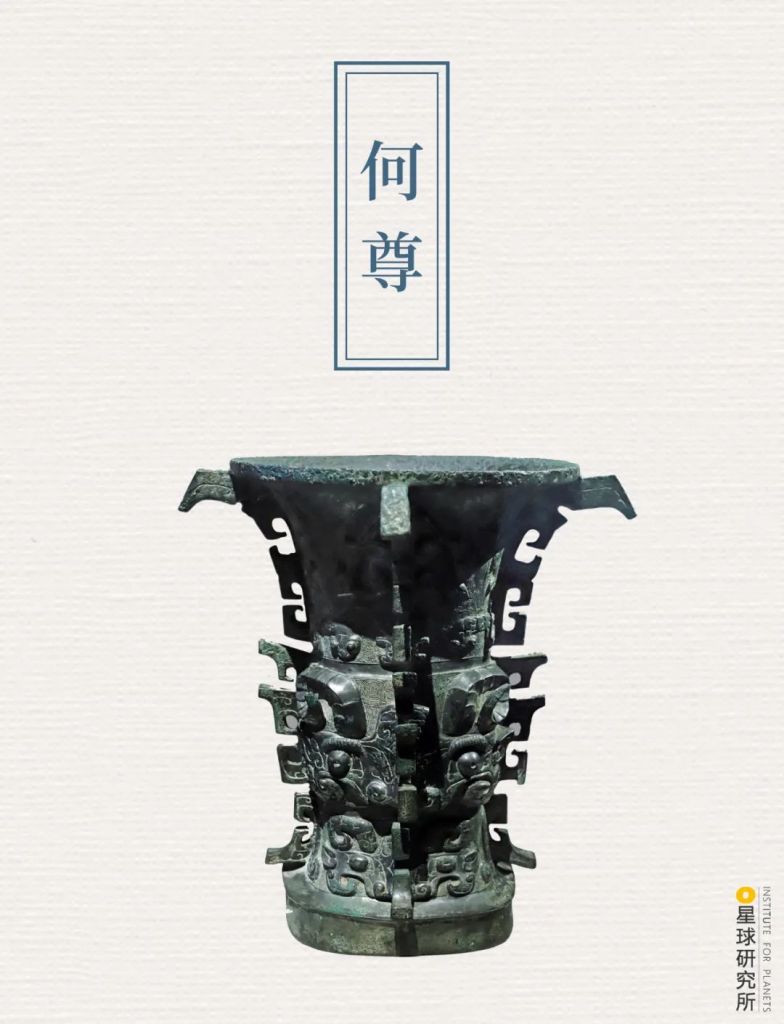

As well as rites, music and ceremonial systems.

Engravings on this wine vessel documented how King Cheng of Zhou established the city of Chengzhou.

The inscription ‘宅兹中国‘ (literally ‘this land here is the middle kingdom’) on it is the earliest record for the concept of 中国 (Middle Kingdom/China)

(photo: 汇图网)

With the consecutive rise and fall of Xia, Shang and Zhou Dynasties, the Chinese civilisation gradually matured. Then in 221BC, when Qin engulfed the six other warring states and united the entire civilisation, mountains and plains further beyond the Yellow River basin were granted the precious opportunity of full scale development.

Large number of lakes and marshes on the downstream floodplains were drained to make way for new farms and villages.

(photo: 田春雨)

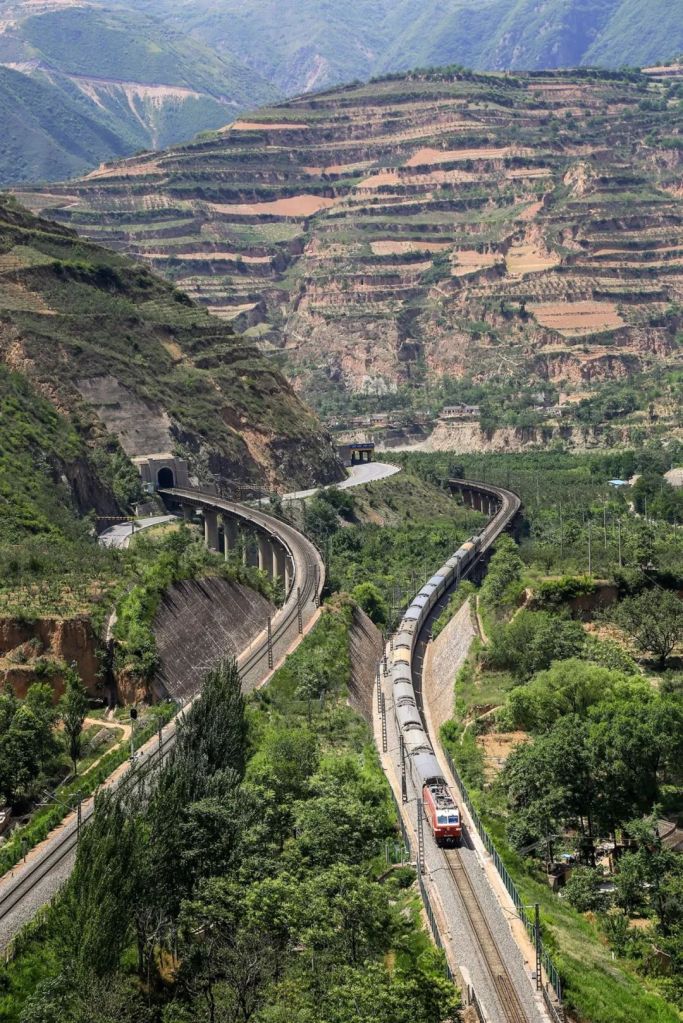

In the midstream, all the loess tablelands, ridges and hillocks on Loess Plateau were transformed into terraced fields.

(photo: 王生晖)

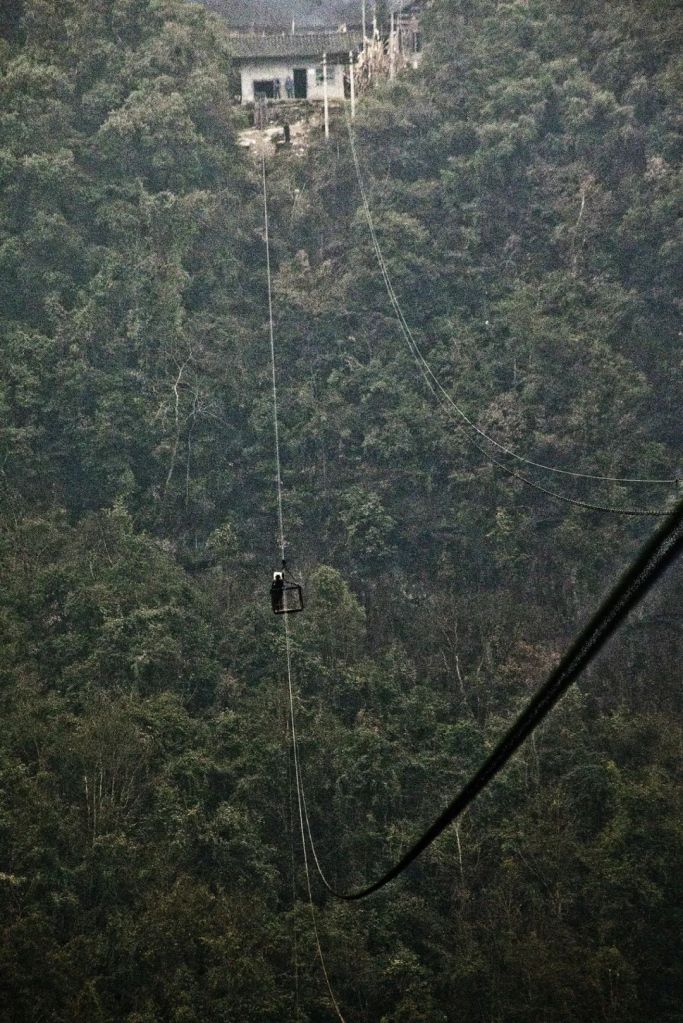

Far out in the upstream, Zhongwei Plain, Yinchuan Plain and Hetao Plain were all rich and fertile lands owing to Yellow River’s generous irrigation. Conditions here were so optimal that these plains were praised the ‘second Jiangnan beyond the Great Wall (塞外江南)‘.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Even the river valleys and basins on Tibetan Plateau were recruited for planting crops.

(photo: 李珩)

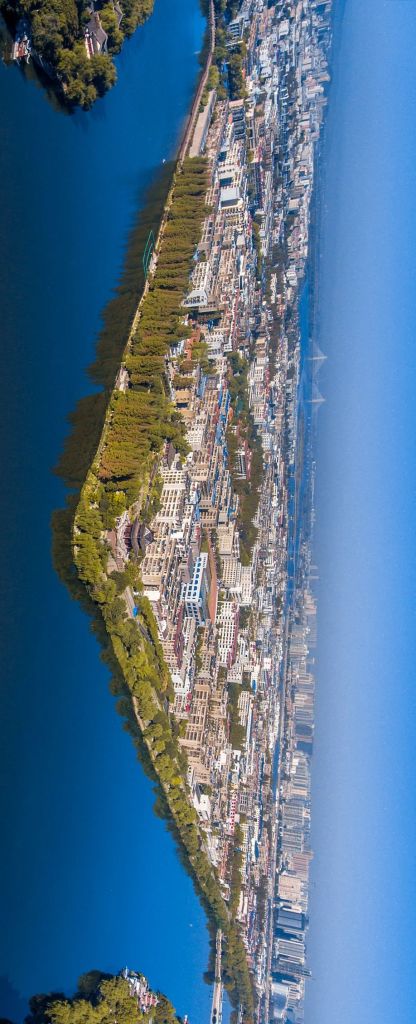

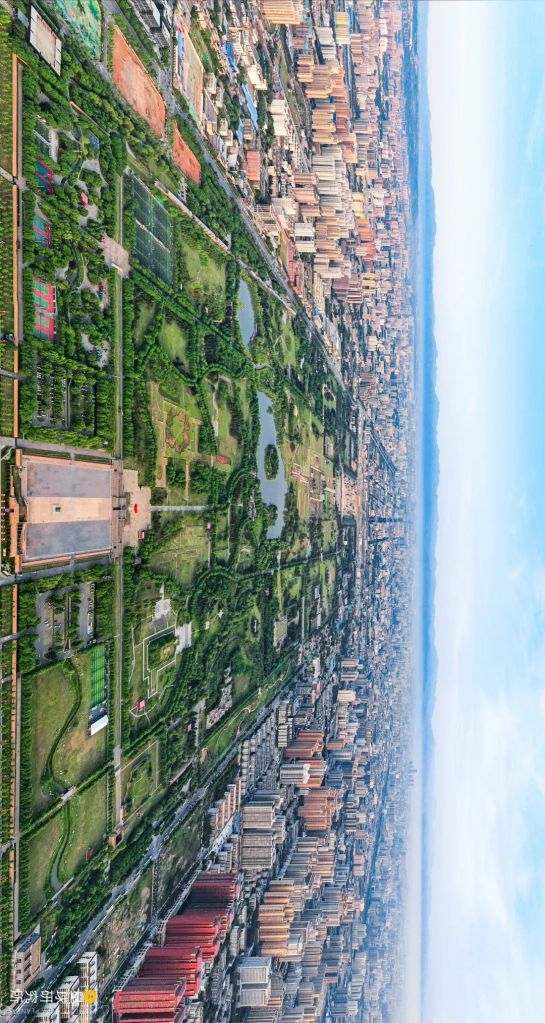

The entire Yellow River basin enjoyed uninterrupted development, which was accompanied by continuous population growth and prospering economy. It also nurtured two very special cities, namely Xi’an on the Weihe Plain.

(photo: 苟秉宸)

And Luoyang on the Yiluohe Plain.

(photo: 傅鼎)

For more than 1000 years, they were the alternating capital cities of China between Qin and Tang Dynasties. Under their leadership, the Chinese civilisation reached the peak of its glory.

(photo: 视觉中国)

4. The rebirth

This is the Yellow River.

As the cradle of Chinese civilisation, it offered everything possible to nurture the land and the people.

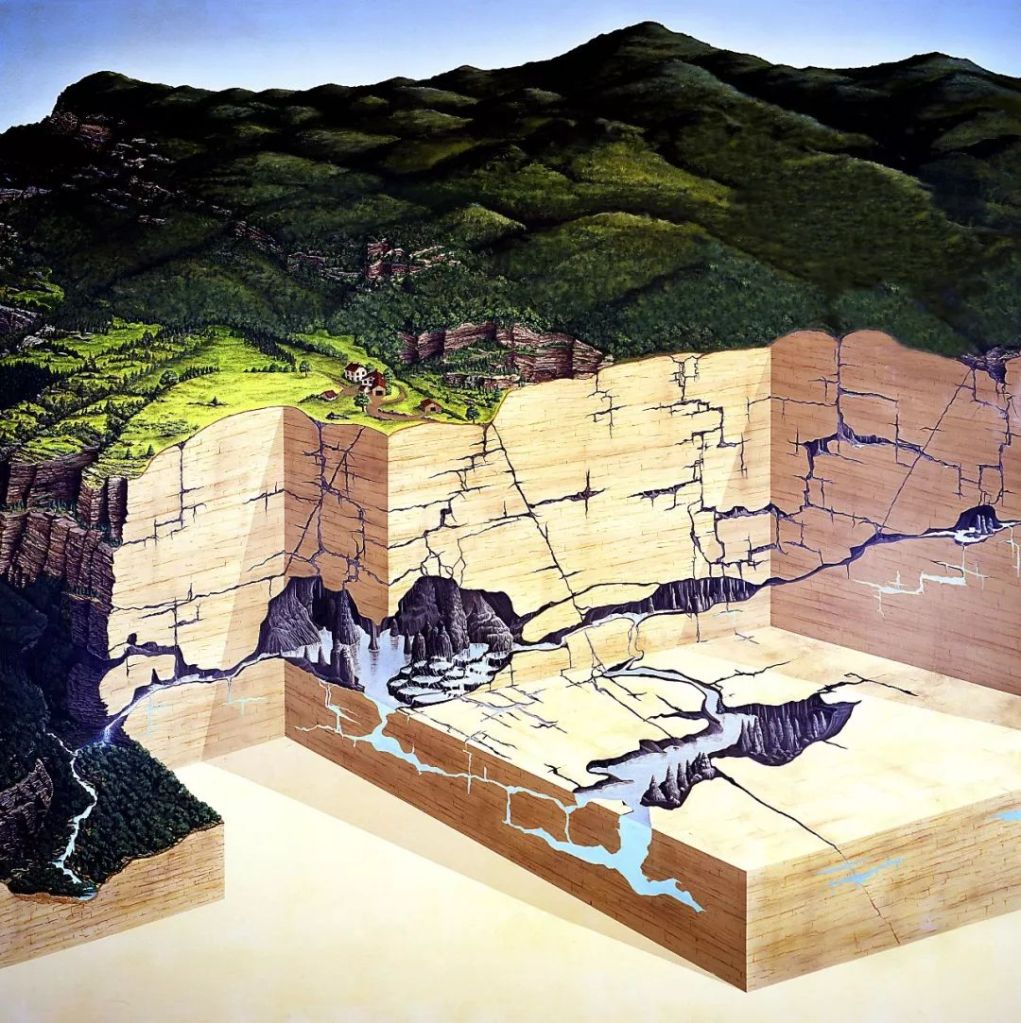

However, continuous agricultural activities on the Loess Plateau since the Spring and Autumn Period had led to massive reduction in natural vegetation coverage along the river basin, and this resulted in severe erosion.

Yellow: Yellow River basin; green: natural vegetation; dotted line: agricultural production border

Dynasties: Qin & Han (秦汉), Tang & Song (唐宋), Ming & Qing (明清), modern (现代)

Cities: Lanzhou (兰州), Yinchuan (银川), Baotou (包头), Hohhot (呼和浩特), Ordos (鄂尔多斯), Yulin (榆林), Taiyuan (太原), Yan’an (延安), Linfen (临汾), Baoji (宝鸡), Xianyang (咸阳), Xi’an (西安), Sanmenxia (三门峡), Luoyang (洛阳), Zhengzhou (郑州)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

Loess Plateau was sliced up into shattered pieces, leaving behind countless ditches and gullies.

(photo: 任世明)

Sand and silt were constantly scraped off as the Yellow River marched through the undulating land.

Surging from the west Yellow River breaches the Kunlun Mountains,

roaring for thousands of miles before it reaches Longmen黄河西来决昆仑,咆哮万里触龙门

Cross Not the River by Li Bai

李白《公无渡河》

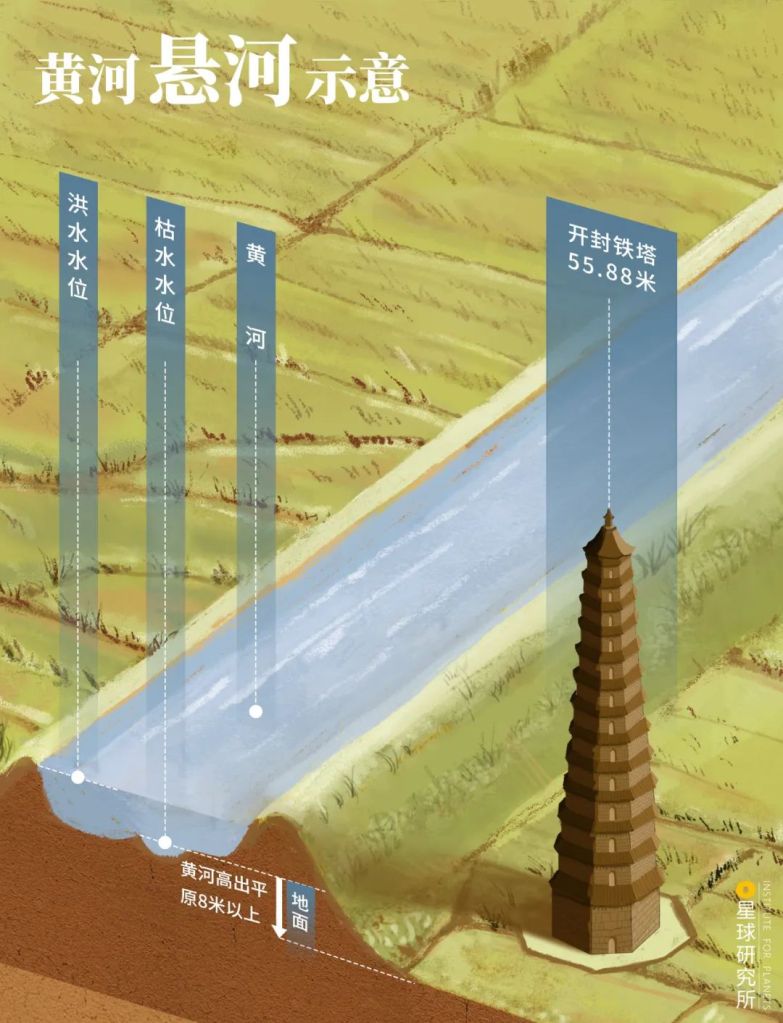

Over time, sedimentation in the river bed turned Yellow River into a hanging stream.

Flooding water level (洪水水位), low water level (枯水水位), Iron Pagoda of Kaifeng (开封铁塔)

The hanging section of Yellow River runs 8 metres above ground level

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

During flood seasons, or whenever spontaneous floods hit, sloppy defence measures were a major reason for breaches in the river banks and potential diversion. Historically, there were more than 1590 breaches, 26 moderate diversions and 5 to 6 major diversions in the downstream between 602 BC and 1949.

Ancient channel (故道) periods: Yu the Great (禹王), Western Han (西汉), Eastern Han (东汉), Northern Song (北宋), Jin & Yuan (金元), Ming & Qing (明清)

Modern: modern Yellow River (现代黄河)

Cities: Beijing (北京), Tianjin (天津), Huanghua (黄骅), Lijin (利津), Ninghai (宁海), Jinan (济南), Lankao (兰考), Hua County (滑县), Zhengzhou (郑州), Mengjin (孟津)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

Diversions were always catastrophic. Every time it occurred, countless farmlands, villages and towns would be submerged, and hundreds of thousands of civilians displaced. Imagine ‘a barren land that stretches thousands of miles (赤地千里)’ in front of you. This also made Yellow River the nation’s sorrow.

With Mengjin as the major hinge, Yellow River has been swinging north towards Tianjin and south reaching Huai River, forming a Yellow River influence region that spans an area of 250,000 km2.

Dotted line: ancient channel of Yellow River (黄河故道), dark shade: major alluvial fan (主要冲积扇), light shade: regions under Yellow River’s influence (黄河影响范围)

Cities: Beijing (北京), Tianjin (天津), Jinan (济南), Zhengzhou (郑州)

Rivers: Yellow River (黄河), Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (京杭运河), Huai River (淮河), Yangtze River (长江)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

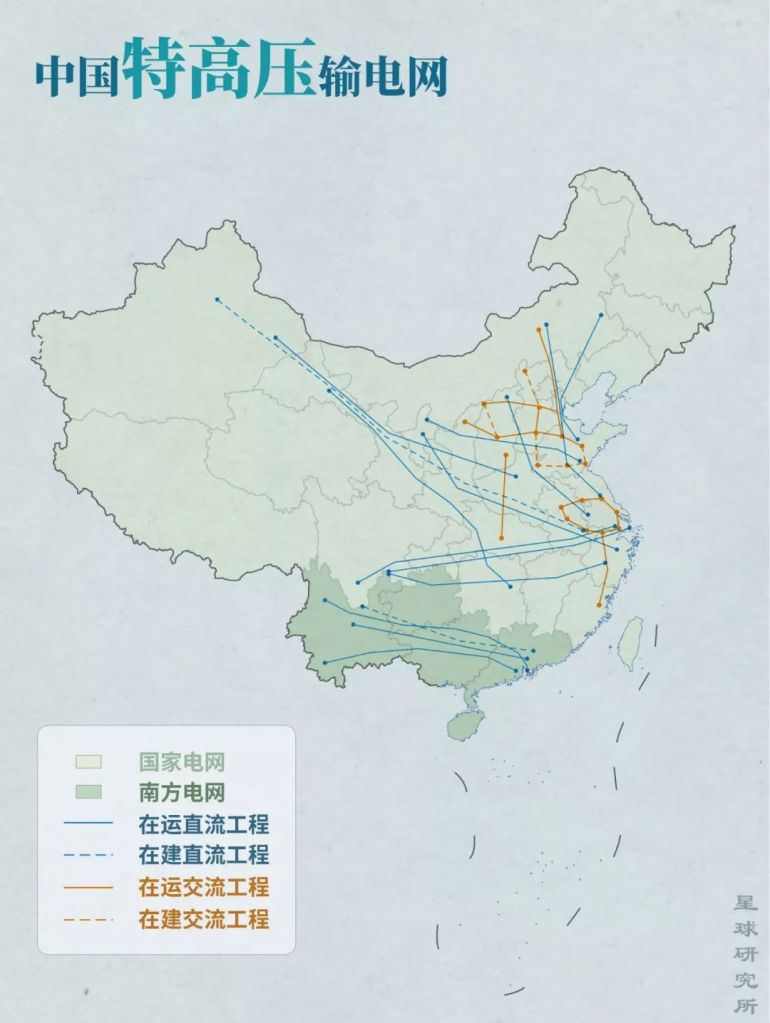

Fortunately, Yellow River today is no longer the raging monster that tends to flood, nor the sandy river always overloaded with sediment. Over the past few decades, a series of hydraulic engineering projects targeting the up- and midstream have been completed.

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

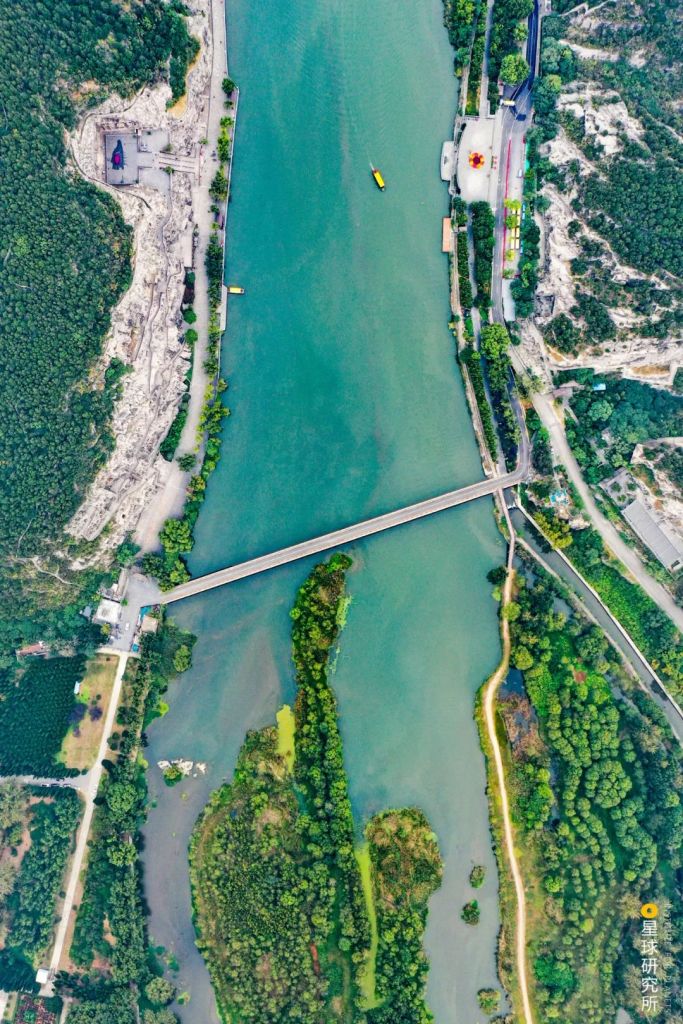

With these projects in place, we are now able to gate the silt with dams, and flush it out when necessary using man-made flood peaks.

To flush out the silt, coordinative discharge will be performed in a number of dams upstream of Xiaolangdi Dam, thereby producing an artificial flood peak that scours the Yellow River

(photo: 李俊博)

(photo: 张子玉)

In addition, afforestation and other measures such as returning farms to forests and grasslands were implemented on Loess Plateau and other locations.

(photo: 射虎)

As vegetation coverage increases substantially, erosion problem is greatly alleviated.

Vegetation coverage (植被覆盖度)

(diagram: 陈景逸&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

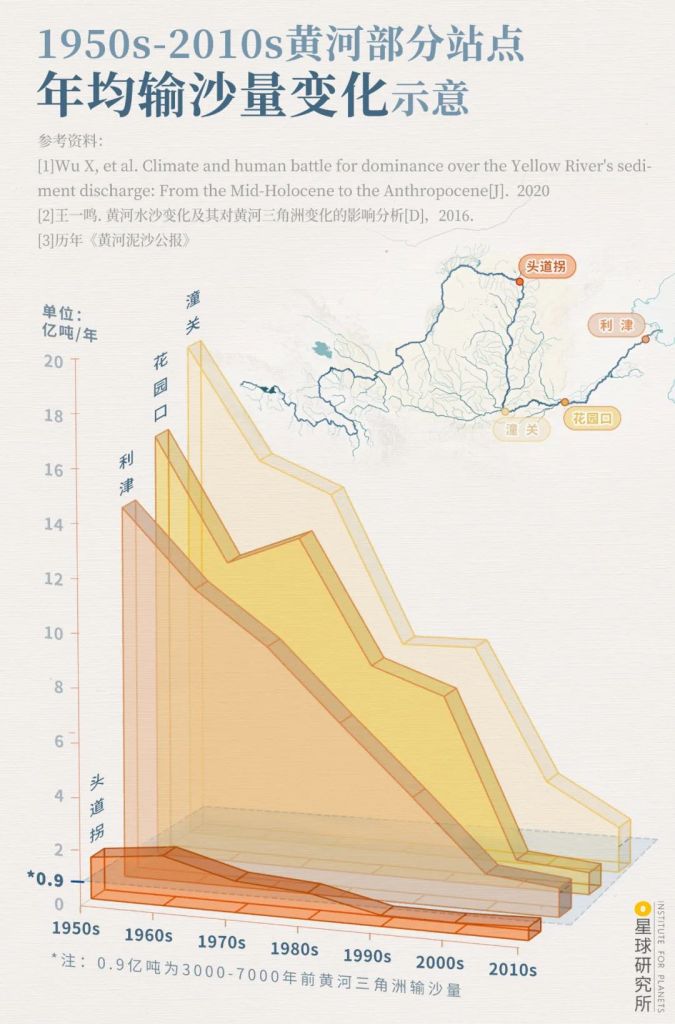

Sediment transport in Yellow River also shows a plunging trend, returning to its natural state 3000 years ago.

During the 1990s, reduction in sediment transport in the downstream was associated with a sharp drop in runoff or even complete cutoff

Toudaoguai (头道拐), Tongguan (潼关), Huayuankou (花园口), Lijin (利津)

(diagram: 王申雯&陈景逸, Institute for Planets)

The title of ‘river with largest sediment transport’ is now given away to the Ganges. In fact, the drop in sediment transport has been so dramatic that, with the concurrent rise in sea level due to global warming, the Yellow River Delta is facing erosion problem.

After peaking at 3061 km2, the area of the delta has since been shrinking rapidly at the river mouth by 2.53 km2/a, which is equivalent to losing an area of 354 football pitches every year

Coastal line in 1855 (1855年海岸线), ancient channel of Yellow RIver (黄河故道), new river mouth (新黄河口), old river mouth (老黄河口), Bohai Sea (渤海), Laizhou Bay (莱州湾)

(photo: google earth)

The Yellow River that was once a great menace to civilians living nearby no longer floods frequently, thanks to the aforementioned control measures and construction of modern dikes.

Shown here is called the spur dike, which extends into the river channel either perpendicularly or in an slanted manner; it is designed to constrict the river bed and protect the banks

(photo: 雾雨川)

Today, the tamed river flows gently.

(photo: 任世明)

Occasional floods are usually well under control, and any damages are minimised. This is also why it seldom appears on headlines nowadays.

(photo: 雾雨川)

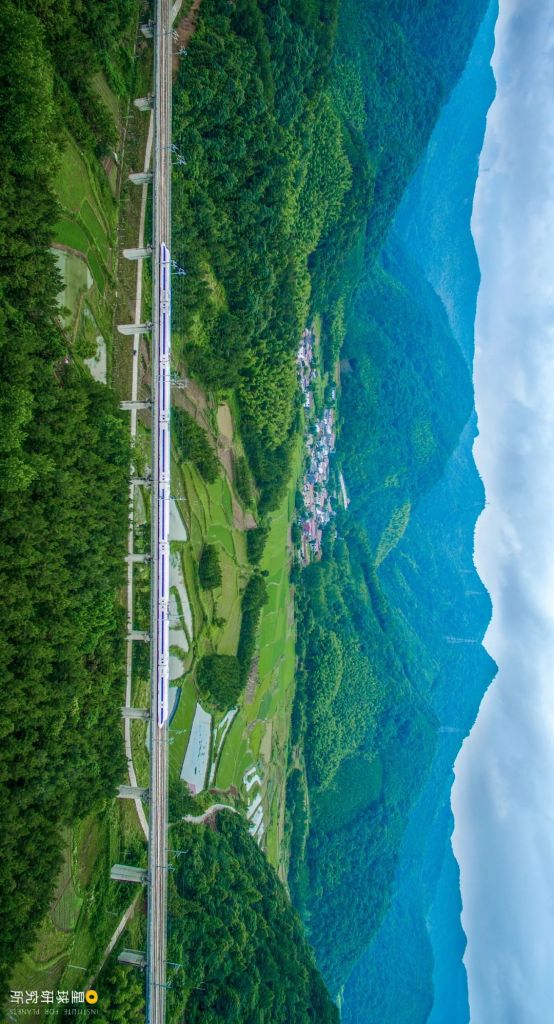

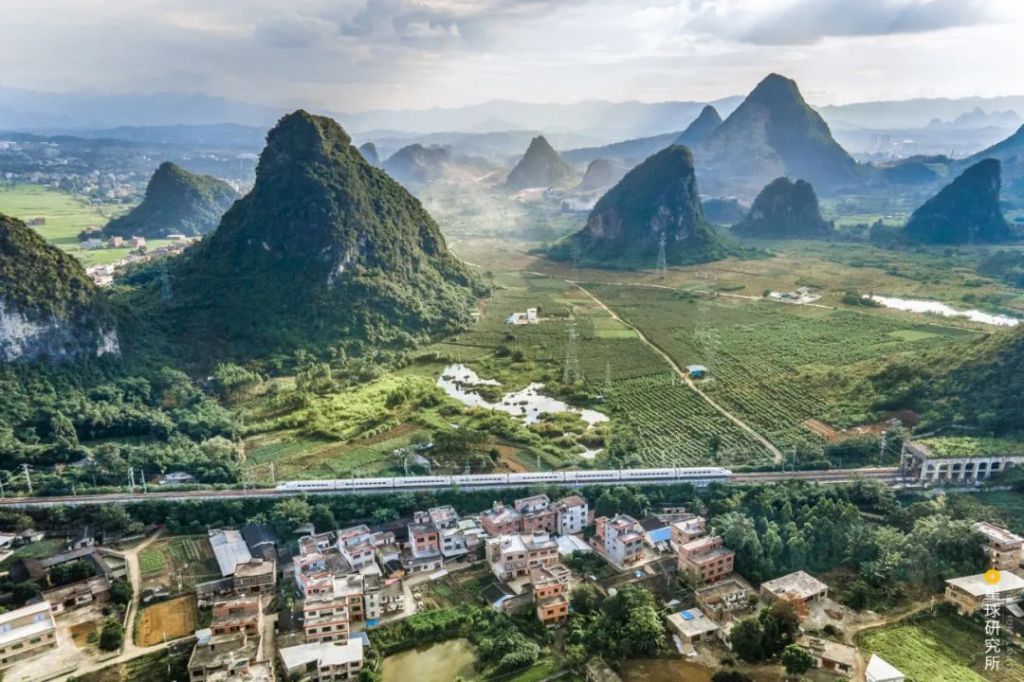

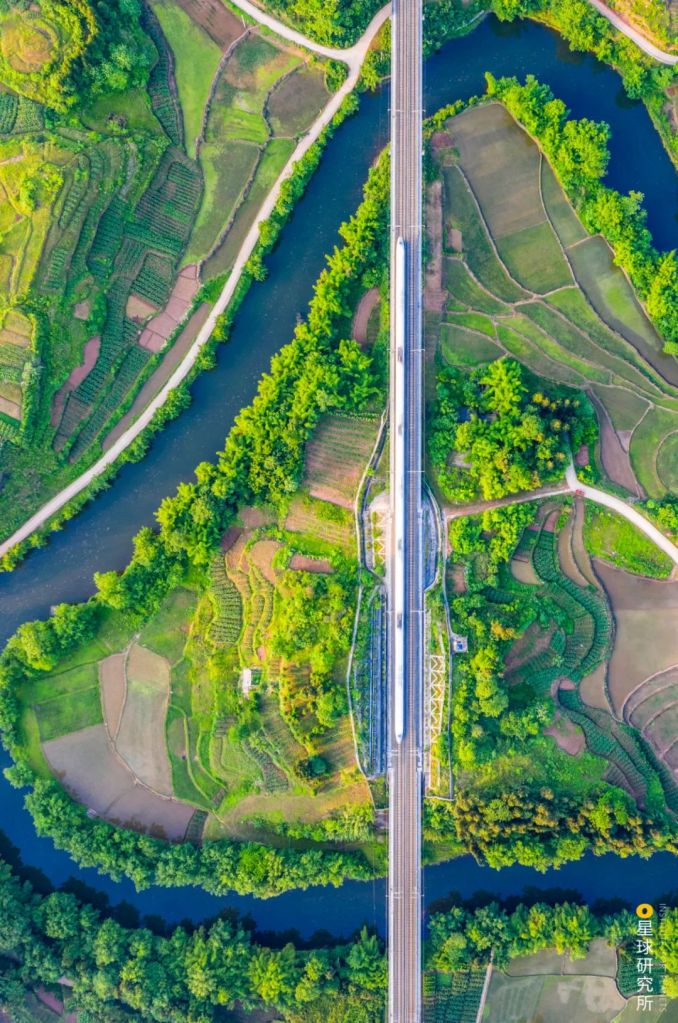

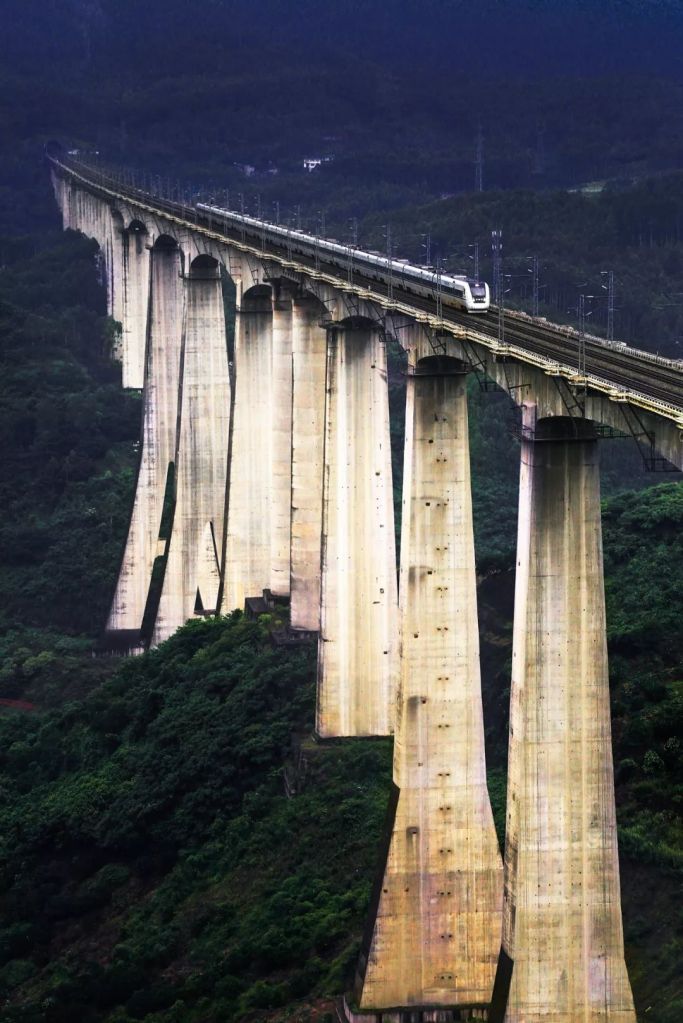

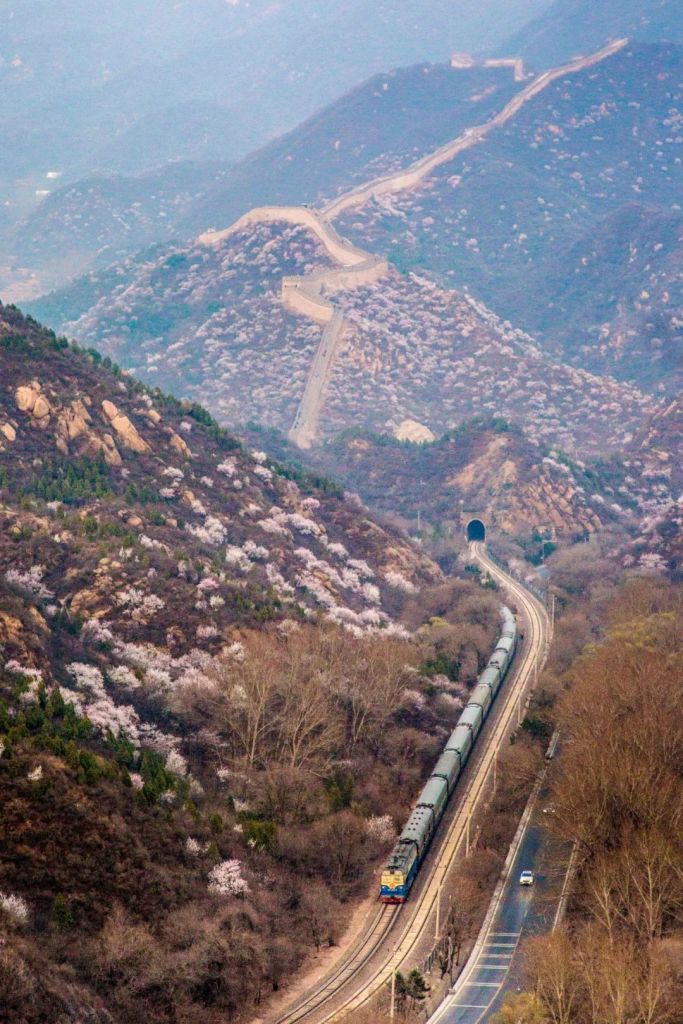

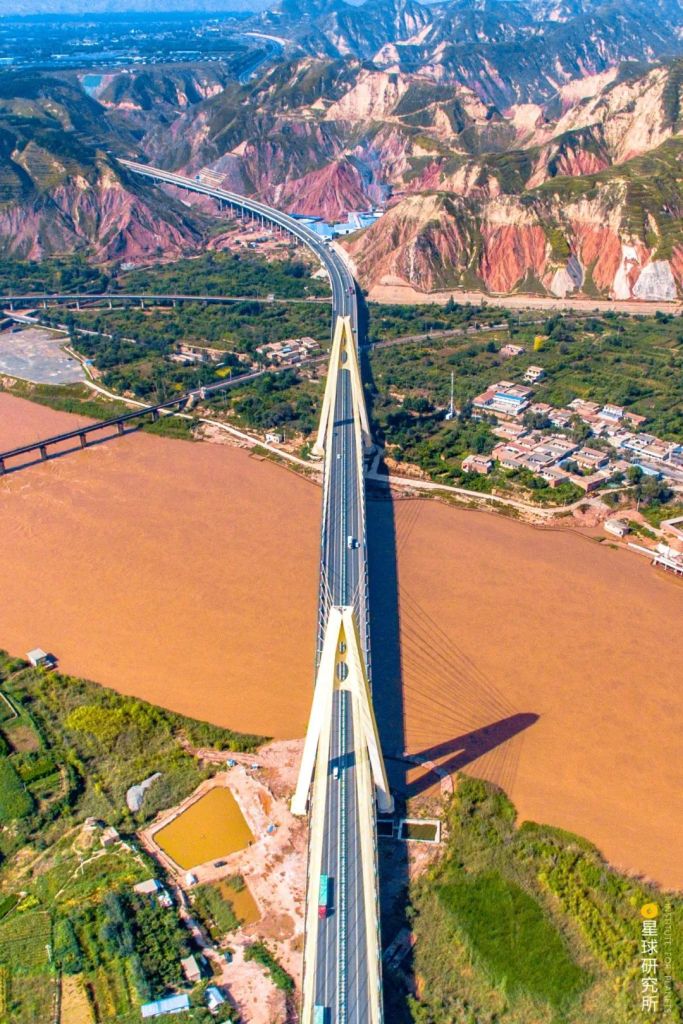

But still, whenever we cross the Yellow River on a highway bridge.

(photo: 陈立稳)

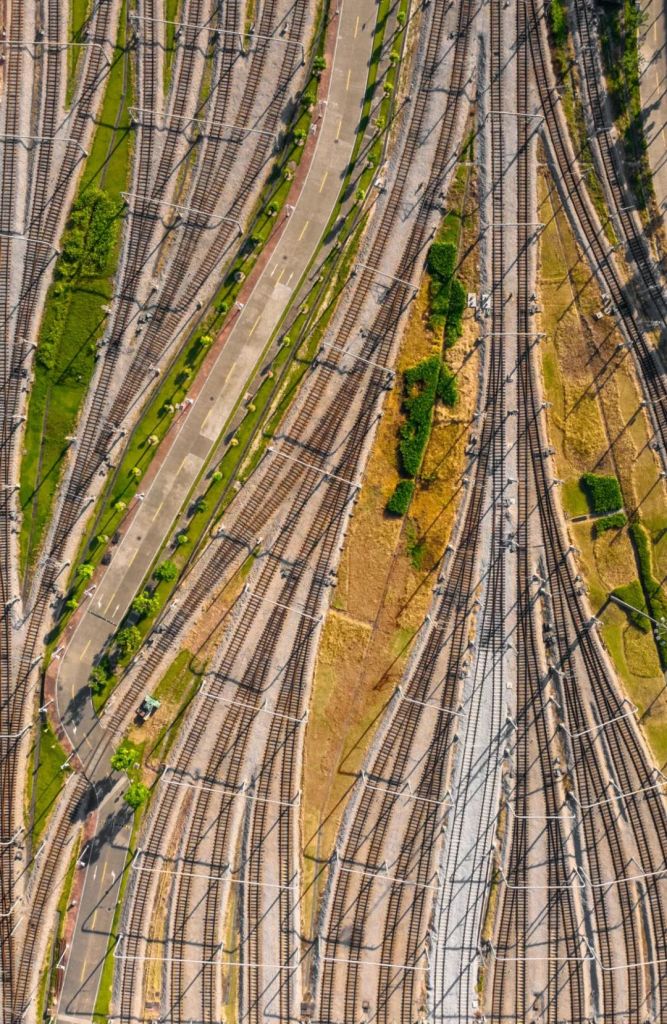

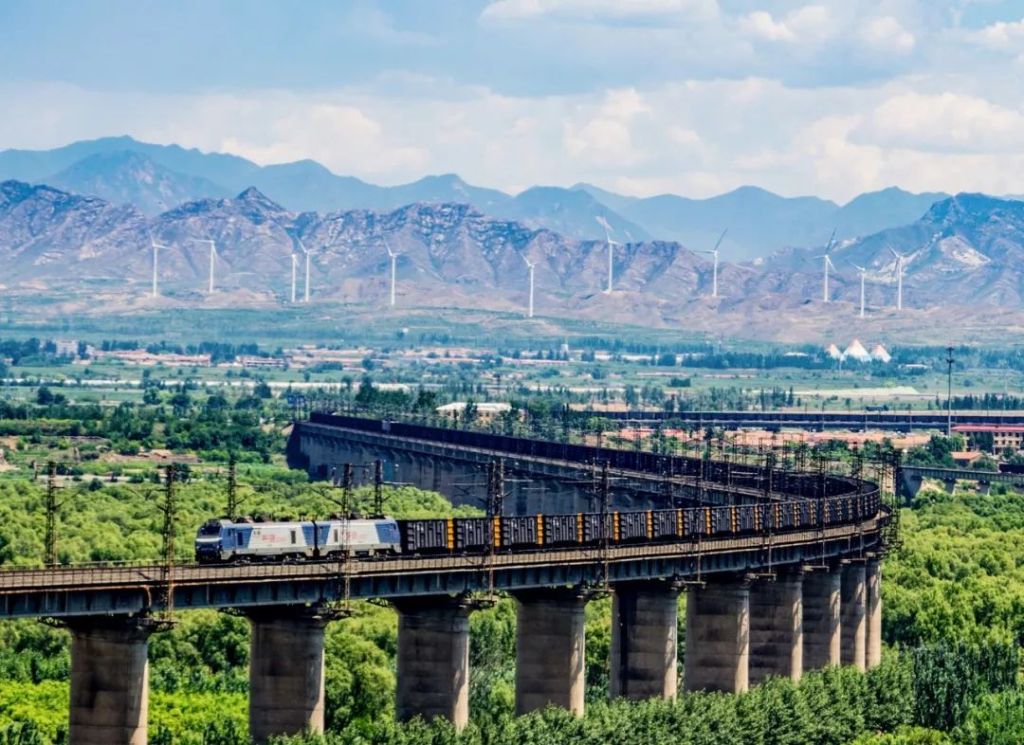

Dash above the river on a high-speed train.

(photo: 中国铁建)

Or fly past it on a plane.

(photo: 吴亦丹)

We cannot help but be absorbed in the enchanting beauty of a river so grand and indispensable to us.

This is the surging power that nurtured a surging nation.

(photo: 王生晖)

Production Team

Text: 风子

Photos: 凰壑

Maps: 陈景逸

Design: 王申雯

Review: 王长春, 云舞空城

Feature photo: 余明

Expert review

Prof. An Chengbang, Lanzhou Unversity (安成邦教授, 兰州大学)

Asst. Prof. Hu Zhenbo, Lanzhou University (胡振波副教授, 兰州大学)

References

[1]王绍武. 全新世气候变化[M]. 气象出版社, 2011.

[2]尤联元,杨景春主编. 中国地貌[M]. 北京:科学出版社, 2013.07.

[3]邹逸麟,张修桂主编;王守春副主编. 中国历史自然地理[M]. 北京:科学出版社, 2013.10.

[4]刘昌明主编;周成虎,于静洁,李丽娟,张一驰副主编. 中国水文地理 中国自然地理系列专著[M]. 北京:科学出版社, 2014.04.

[5]黄河水利委员会黄河志总编辑室编. 黄河志 卷2 黄河流域综述[M]. 郑州:河南人民出版社, 2017.01.

[6]苏秉琦著. 中国文明起源新探[M]. 北京:人民出版社, 2013.08.

[7]刘莉, 陈星灿. 《中国考古学:旧石器时代晚期到早期青铜时代》[J]. 读书, 2017(09):29.

[8]许宏著作. 先秦城邑考古[M]. 北京:西苑出版社, 2017.08.

[9]许宏著. 何以中国 公元前2000年的中原图景[M]. 北京:生活·读书·新知三联书店, 2016.05.

[10]张新斌主编. 黄河流域史前聚落与城址研究[M]. 北京:科学出版社, 2010.02.

[11]韩建业著. 早期中国 中国文化圈的形成和发展[M]. 上海:上海古籍出版社, 2015.05.

[12]王均平. 黄河中游晚新生代地貌演化与黄河发育[D].兰州大学,2006.

[13]胡振波. 晋陕黄河晚新生代水系发育与河流阶地研究[D].兰州大学,2012.

[14]郭炼勇. 黄河豫西段形成演化研究[D].兰州大学,2017.

[15]李容全,邱维理,张亚立,张本昀. 对黄土高原的新认识[J]. 北京师范大学学报(自然科学版),2005(04):431-436.

[16]李吉均, 方小敏. 晚新生代黄河上游地貌演化与青藏高原隆起[J]. 中国科学:D辑, 1996, 26(4):316-316.

[17]刘志杰, 孙永军. 青藏高原隆升与黄河形成演化[J]. 地理与地理信息科学, 2007, 23(001):79-82.

[18]韩建恩, 邵兆刚, 朱大岗,等. 黄河源区河流阶地特征及源区黄河的形成[J]. 中国地质, 2013, 40(005):1531-1541.

[19]董广辉, 刘峰文, 杨谊时,等. 黄河流域新石器文化的空间扩张及其影响因素[J]. 自然杂志, 2016, 038(004):248-252.

[20]范毓周. 河南巩义双槐树”河洛古国”遗址浅论[J]. 中原文化研究, 2020(4).

[21]谷飞,陈国梁. 社会考古视角下的偃师商城——以聚落形态和墓葬分析为中心[J]. 中原文22,2019(05):84-94.

[22]刘绪. 夏末商初都邑分析之一——二里头遗址与偃师商城遗存比较[J]. 中国国家博物馆馆刊,2013(09):6-25.

[23]曾婧. 偃师商城宫城与郑州商城宫殿区的比较研究[J]. 文博学刊,2019(02):32-45.

[24]夏正楷,张俊娜. 黄河流域华夏文明起源与史前大洪水[A]. 北京大学、北京市教育委员会、韩国高等教育财团.北京论坛(2013)文明的和谐与共同繁荣——回顾与展望:“水与可持续文明”圆桌会议论文及摘要集[C].北京大学、北京市教育委员会、韩国高等教育财团:,2013:16.

[25]Hu Z B , Li M H , Dong Z J , et al. Fluvial entrenchment and integration of the Sanmen Gorge, the Lower Yellow River[J]. Global and planetary change, 2019, 178(JUL.):129-138.

[26]Wu X, Wang H, Bi N, et al. Climate and human battle for dominance over the Yellow River’s sediment discharge: From the Mid-Holocene to the Anthropocene[J]. Marine Geology, 2020: 106188.

…The End…

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光