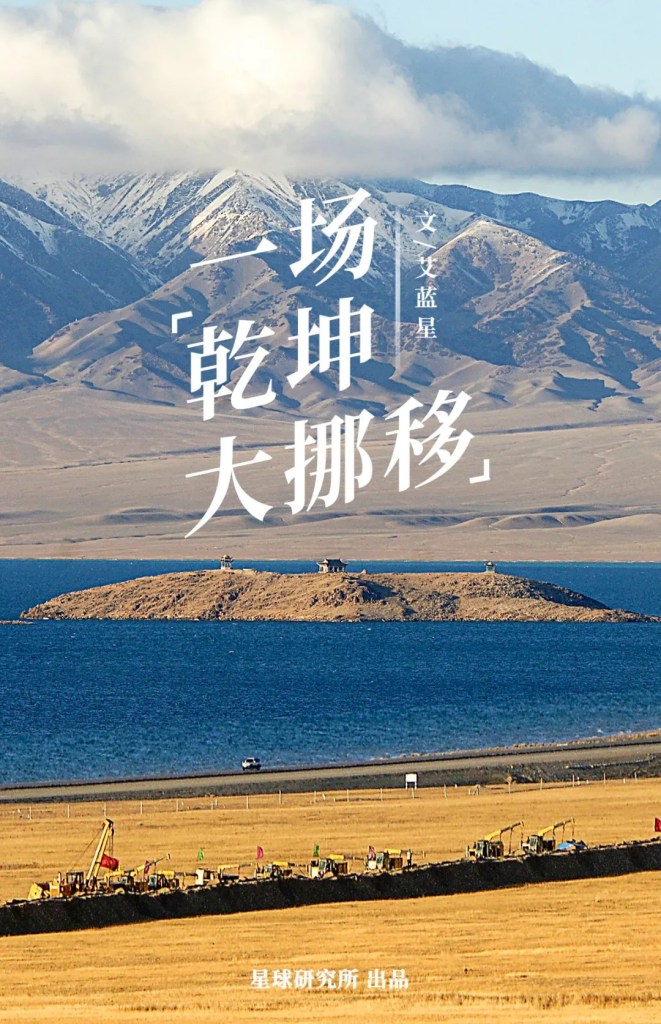

Original piece: 西 气 如 何 东 输 ?

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 艾蓝星

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

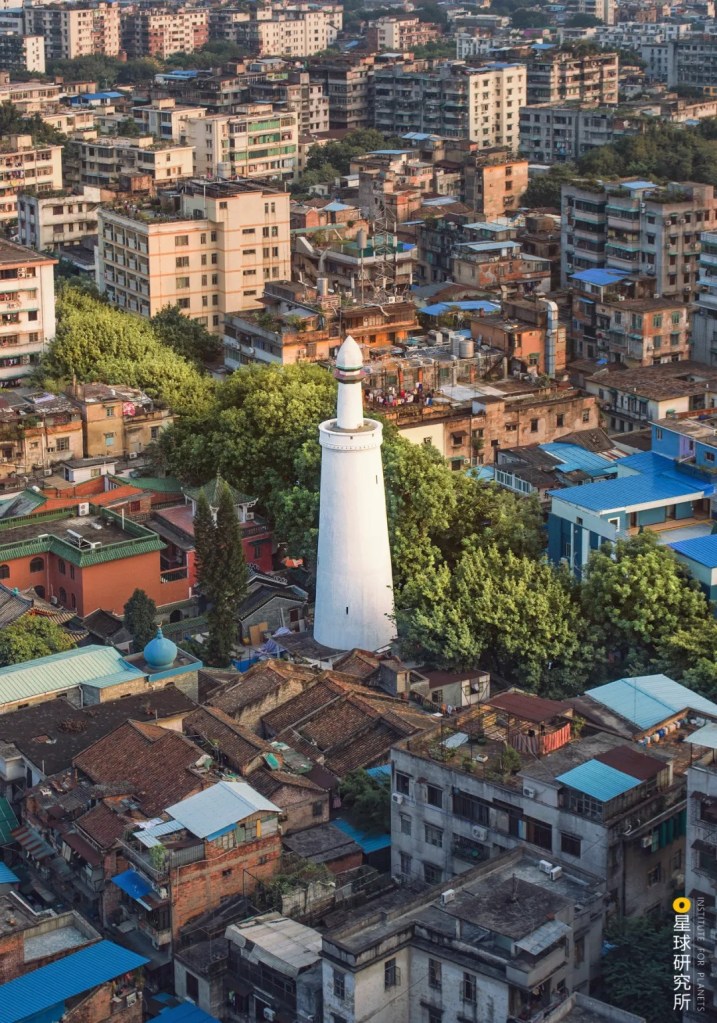

Natural gas is leaving its mark in China.

From somewhere off your radar, 400 million cubic metres of natural gas has to be transported to Guangzhou every year, so that the 2.58 million households may stay warm and be well-fed with cooked food; and 6.9 billion cubic metres of natural gas must be delivered to Shanghai every year, just to make sure the 130 thousand enterprises can run their factories and sustain the production lines.

(photo: 视觉中国)

This is happening not just to Guangzhou and Shanghai, but all over the country. Each year, hundreds of billions of cubic metres of natural gas is being transported, from locations you are probably unaware of, to every corner of the country through 87,000 kilometres of pipelines. It allows 96% of all cities in China to maintain normal production and 400 million Chinese people to go about their daily lives.

(photo: 国家管网集团官方微信)

All this precious natural gas comes not from within Guangzhou or Shanghai, but from western China or the Gobi Desert further away in Central Asia…

(photo: 视觉中国)

…the vast snowfields of Siberia…

(photo: 视觉中国)

…and even across the sea.

(photo: 发菜发菜)

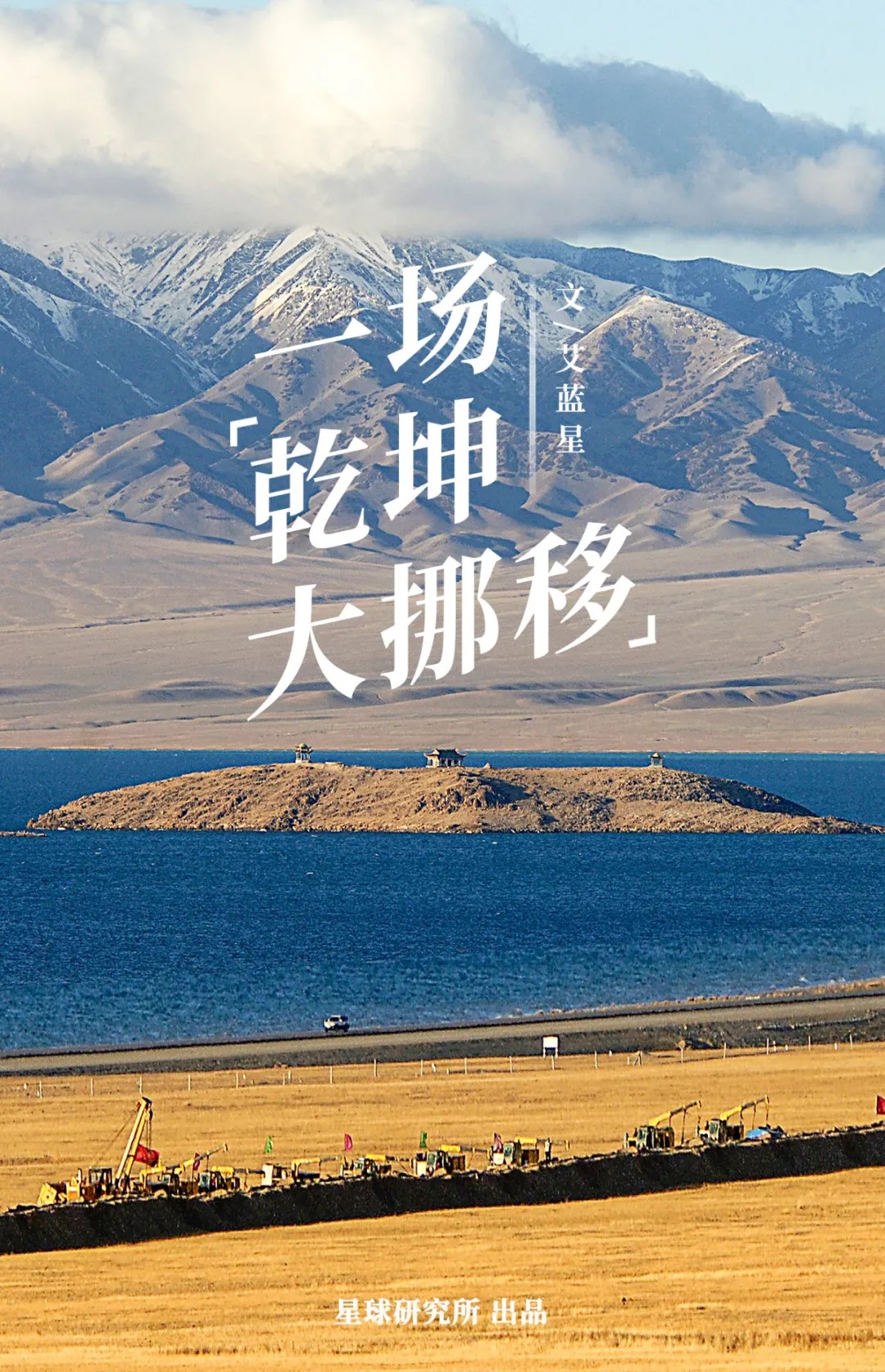

It climbs mountains, swims across the sea and travel tens of thousands of miles to enter every city and factories scattered all over China. The West-East Gas Pipeline, Sichuan-East China Gas Pipeline, Central Asia-China Gas Pipeline, Sino-Myanmar Pipeline and China-Russia Pipeline together constitute China’s natural gas transportation network.

This is a colossal scale reallocation of natural gas resources, an arduous task that is comparable to moving the mountains, or “shifting the Heaven and Earth (乾坤大挪移)” for the Chinese people.

But why are we building such an enormous network? And how did we achieve this?

1. Clean energy

Back in 1999 when the Asian financial crisis had barely died down, China’s GDP was soaring with a growth rate almost hitting 8%. To sustain the astonishing economic development within this one year, the entire country consumed 1.3 billion tonnes of coal in total, and at the same time emitted 11 million tonnes of soot, 18 million tonnes of sulphur oxides and 11 million tonnes of nitrogen oxides into the atmosphere.

Photo was for illustration purpose and not taken in 1999

(photo: 邱会宁)

It was this year when more than 60% of all cities in China failed to meet the National Ambient Air Quality Class 2 Standard (GB3095-1996) because of overwhelming pollutants in the air.

Photo was for illustration purpose and not taken in 1999

(photo: 李珩)

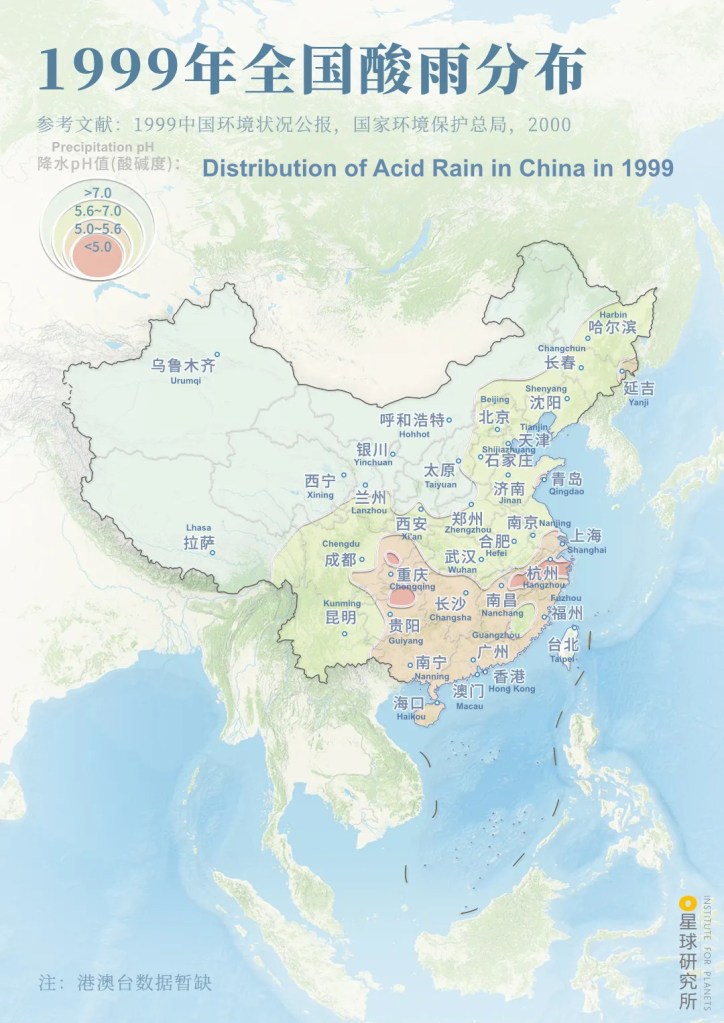

Almost 30% of the land in China was severely polluted by acid rain when emitted sulphur oxides and nitrogen oxides dissolved in the falling water. From vegetation to buildings, soil and water bodies, nothing on land was spared.

Atmospheric precipitation, including rain, snow, hail and dew, with a pH <5.6 are all categorised as acid rain. They are mainly caused by the conversion of sulphur dioxide and nitrogen oxides into sulphuric acid and nitric acid in the atmosphere or water droplets.

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

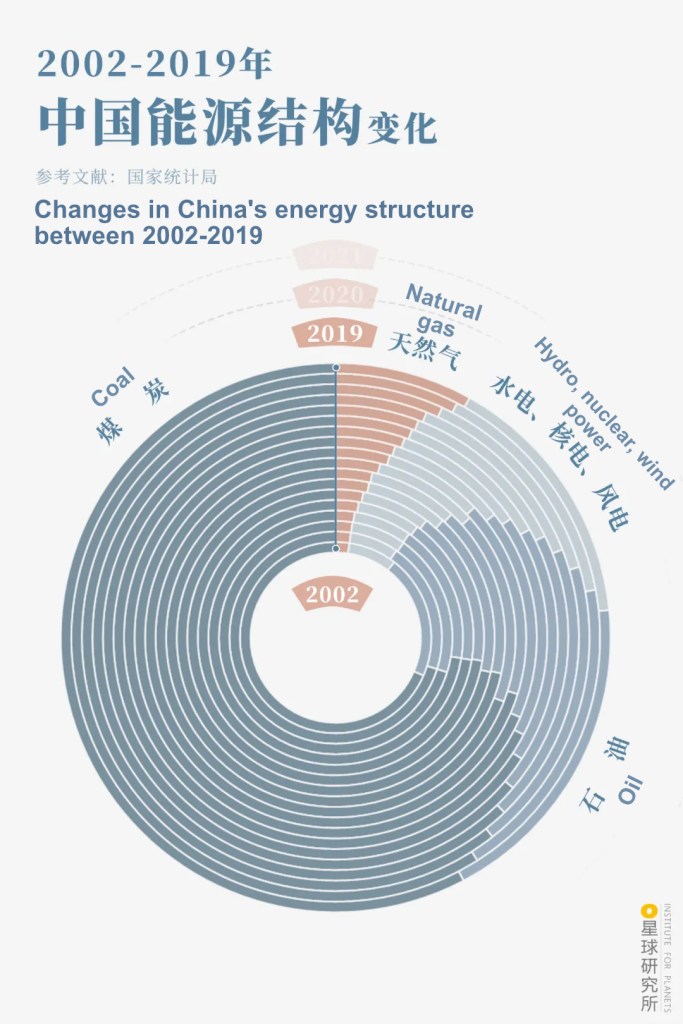

This was not coincidental. In this major “country of coal”, coal plays an indispensable role in China’s primary energy* and still accounts for up to 60% of all the energy sources today. Prior to the widespread use of clean energy, the long-term extensive use of coal had been slowly degrading the fragile ecosystem.

*Primary energy refers to energy forms that are harvested directly from nature without undergoing artificial processing or conversion.

The rapidly developing China had never wanted an energy reform so badly. To that end, many research proposals on clean coal utilisation were put on the agenda, and immense effort was made to hunt for cleaner alternatives.

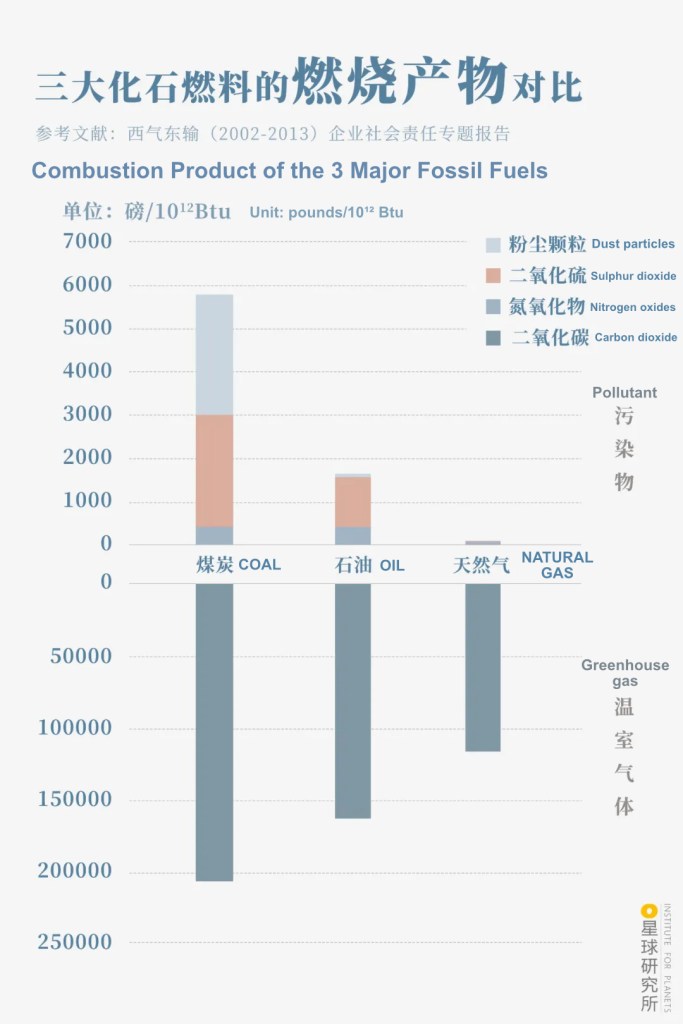

People began to set their eyes on natural gas. Composed of methane primarily, this gaseous fuel generates predominantly carbon dioxide and water during combustion, with almost no emission of sulphur oxides and soot.

Besides, for the same amount of heat produced, the carbon dioxide emission of methane combustion is merely 56% and 71% of that of coal and oil, respectively.

Data was empirically measured by the US Department of Energy

Both pounds and Btu are non-metric units, where 1 pounds is approximately 0.45 kg and 1 Btu is approximately 1055 joules

(diagram: 杨宁, Institute for Planets)

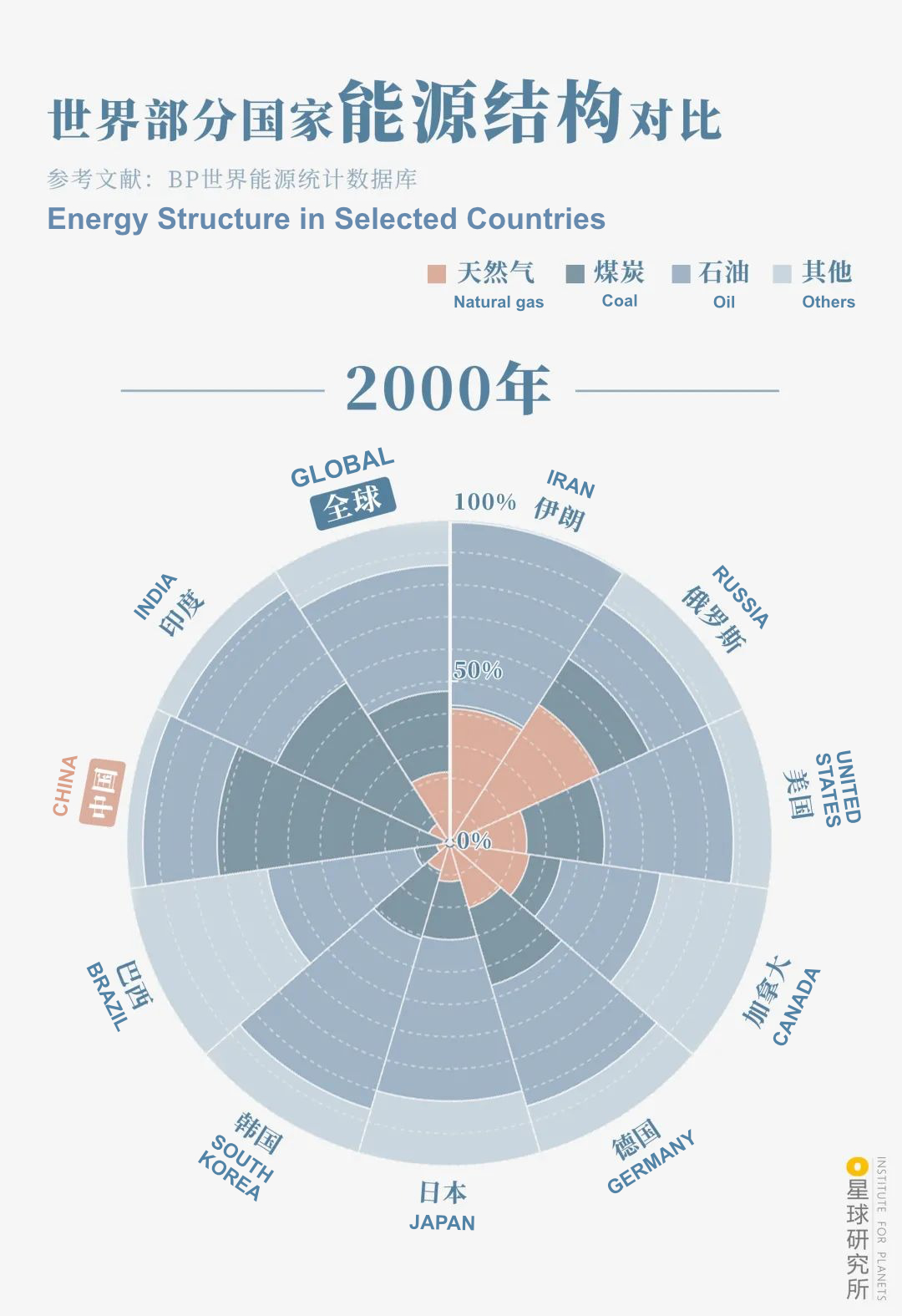

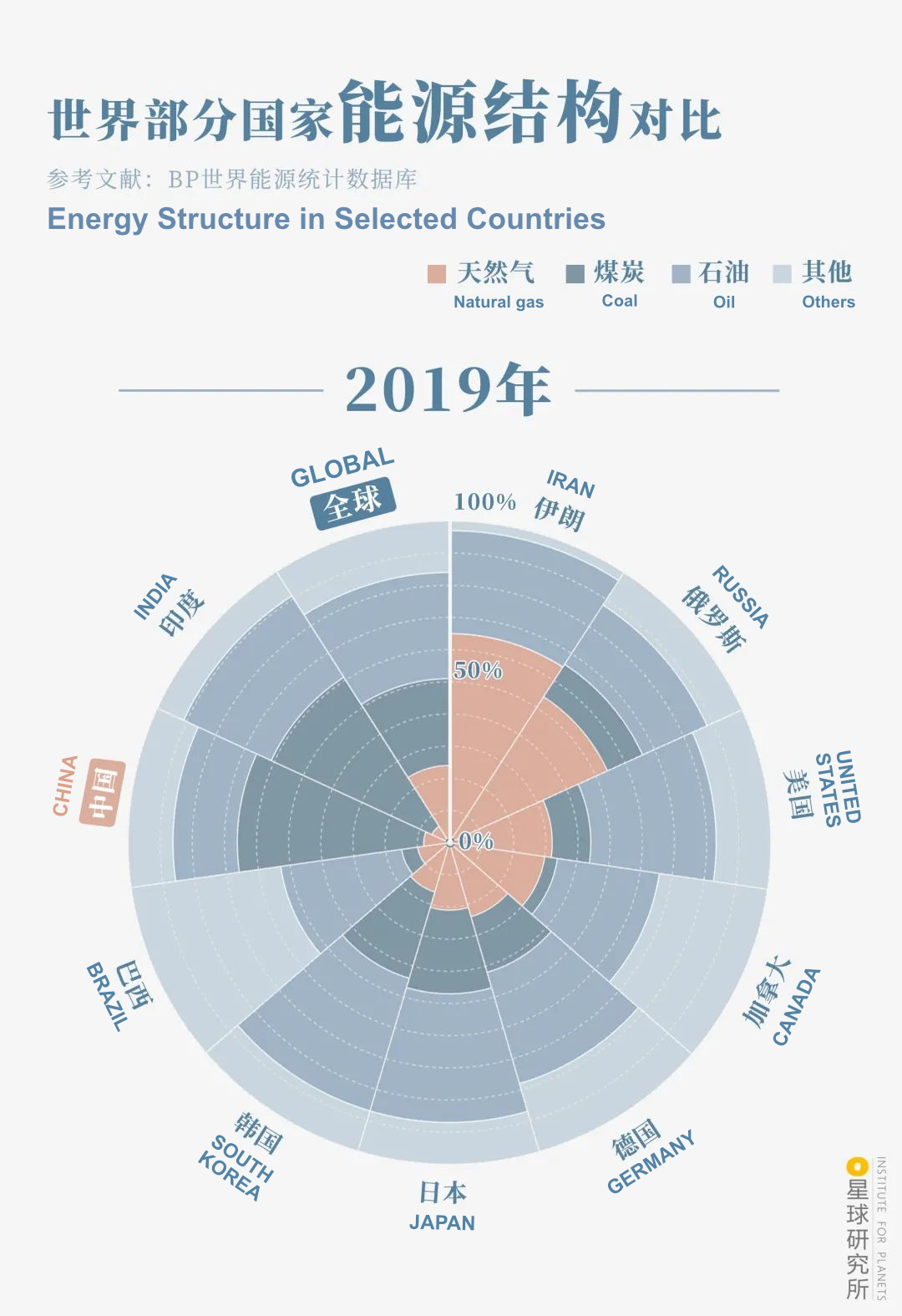

Since natural gas is much cleaner and emits much less carbon, it stands out from other fossil fuels and is utilised by countries around the world. It is becoming increasingly critical in the global energy structure.

(diagram: 杨宁, Institute for Planets)

TO COMPARE BETWEEN DATA IN 2000 AND 2019, PRESS AND SWIPE PHOTO LEFT AND RIGHT

Natural gas also gained a similar “fame” rapidly within China. After almost 20 years of development, it has now entered many sectors including industry, transportation and households. In 2020, the entire country consumed 325.9 billion cubic metres of natural gas, which is equivalent to the total volume of 58 Tai Lake combined.

diagram: 杨宁, Institute for Planets)

Here comes the question —

Where does all this natural gas come from?

2. Where is the gas?

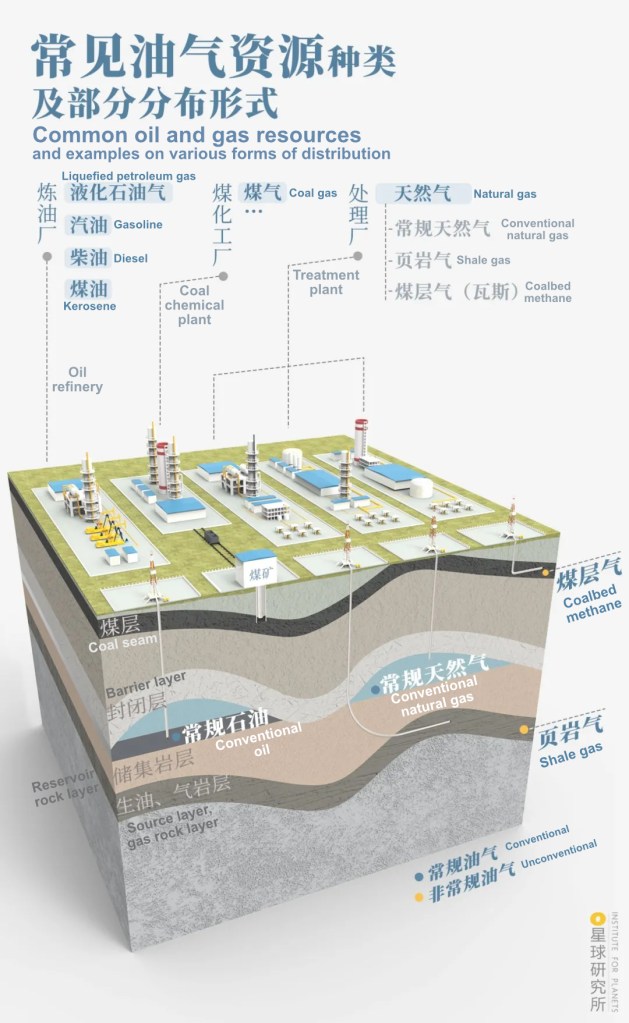

To answer this question, let us first shift our focus to the underground.

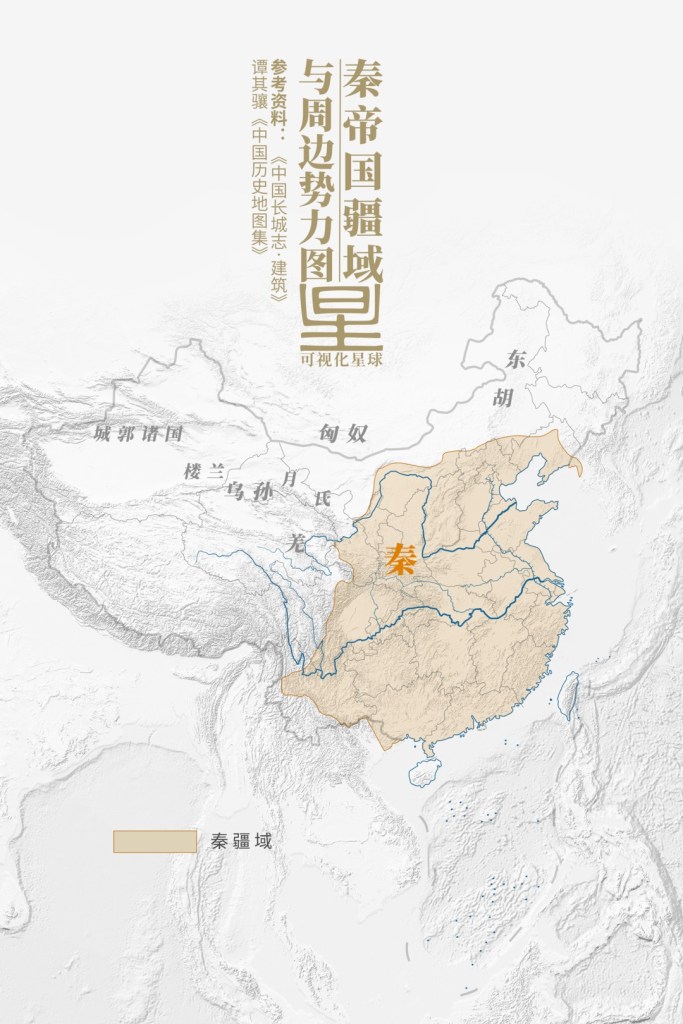

For billions of years, all kinds of organisms had continued to emerge on this blue planet. They grew, reproduced, died, and repeated this life cycle over and over. As land subsidence persisted, their remains were buried under layers of sediment, where they were converted into various forms of fossil fuels under the effects of high temperature and pressure as well as microbial activities. Among these, biological remains of higher plants were converted into coal, consolidated and sealed between strata.

The light-coloured zone is the overlaying stratum of the coal seam

(photo: 饶颖)

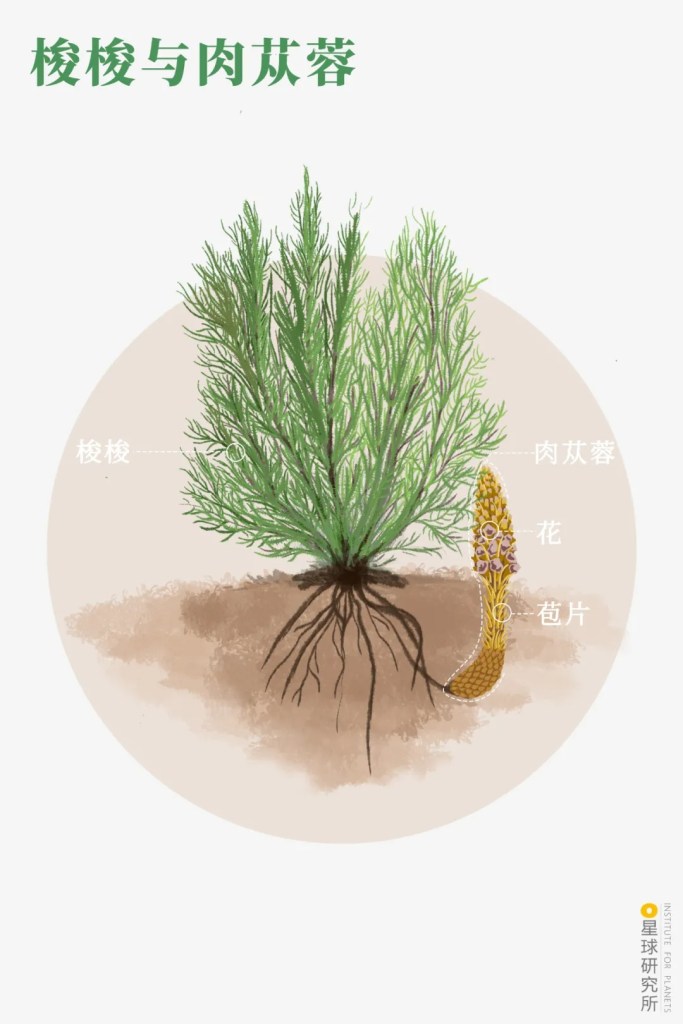

Biological remains of planktons, on the other hand, turned into oil and natural gas, which are the primary source of oil and gas fuel on Earth.

There is also a type of inorganic gas fuel which forms naturally without the involvement of any organisms. It is formed from various elements through reactions like crustal movement, magmatism and metamorphism.

(photo: 咸鱼)

Liquid oil and gaseous natural gas are not always stable. Once formed, they may migrate and aggregate, sometimes occupying a large space together, other times existing alone elsewhere. Nonetheless, both have become the conventional oil and gas resources which are subject to extensive mining by humans. Conversely, oil and gas in some places may keep a low profile and stay where they are born. Since these resources are more difficult and costly to mine, they are known as the unconventional oil and gas resources.

This article will focus exclusively on conventional natural gas

(diagram: 罗梓涵)

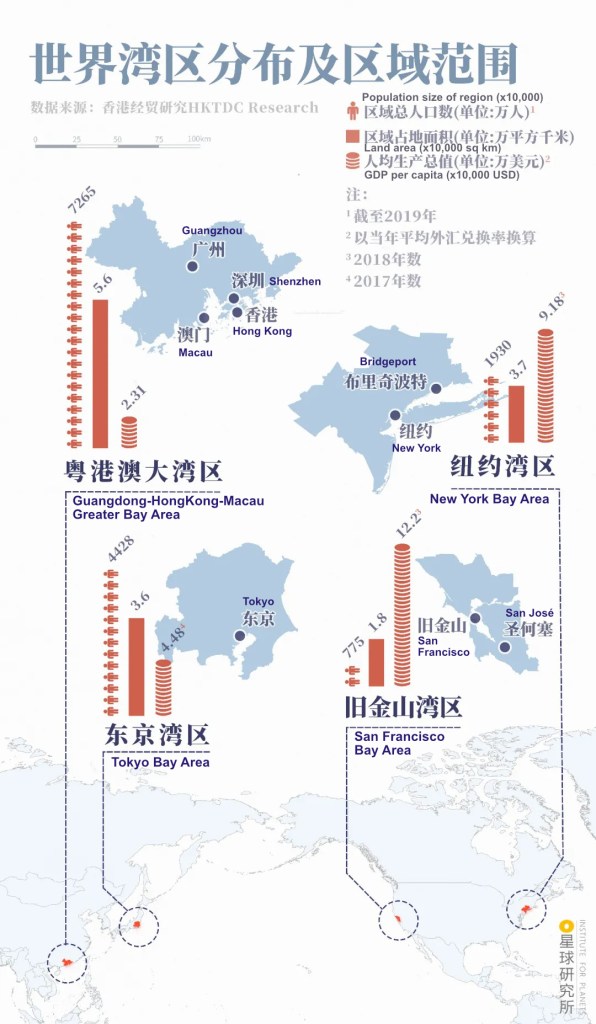

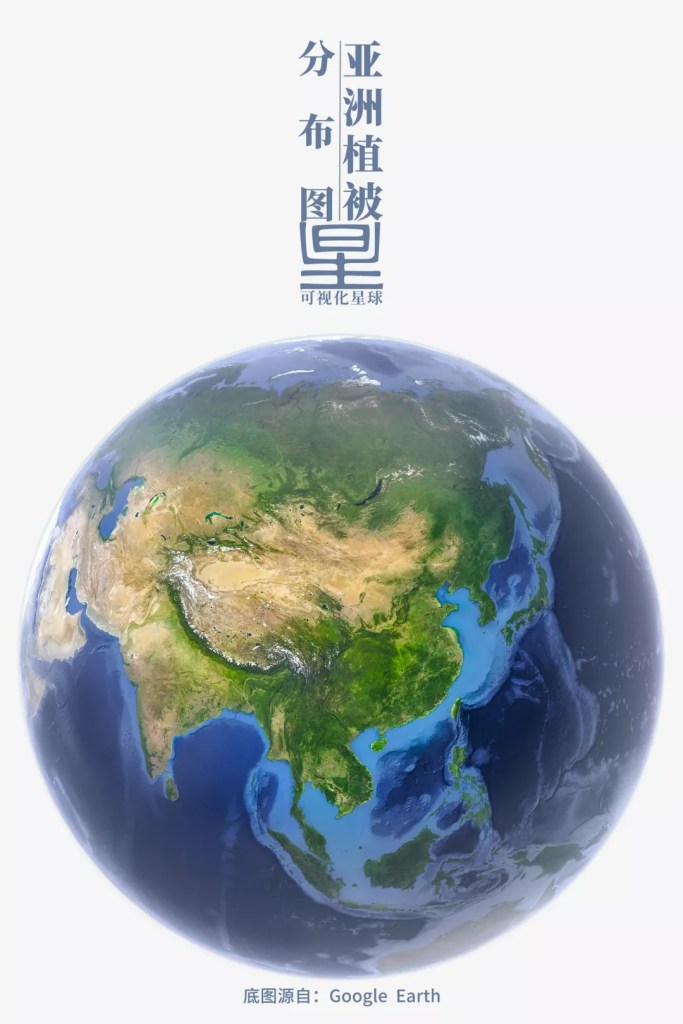

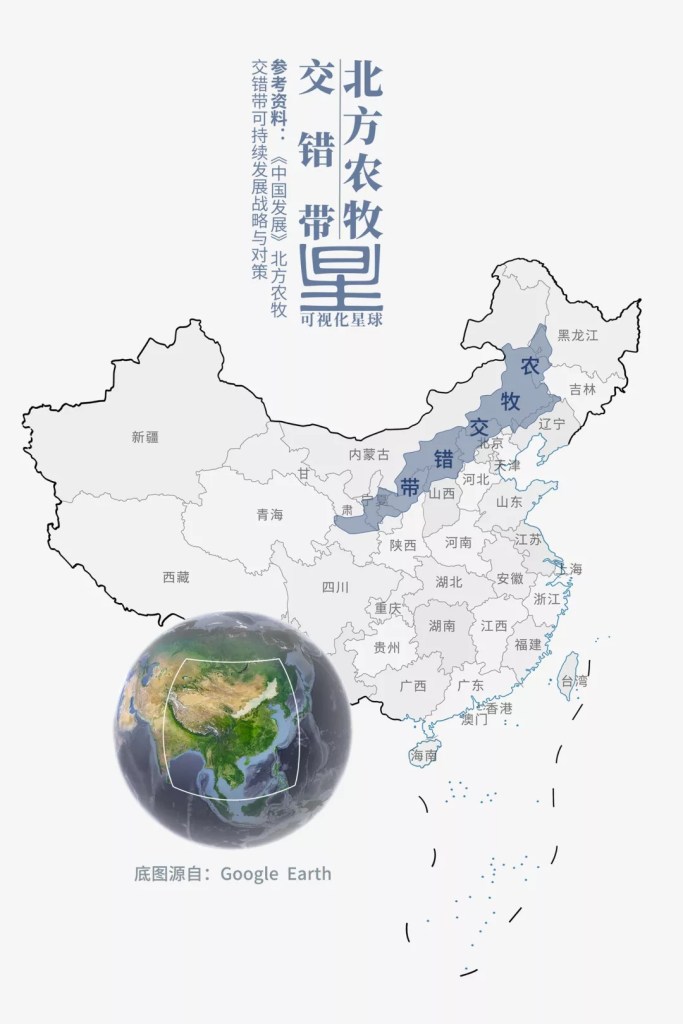

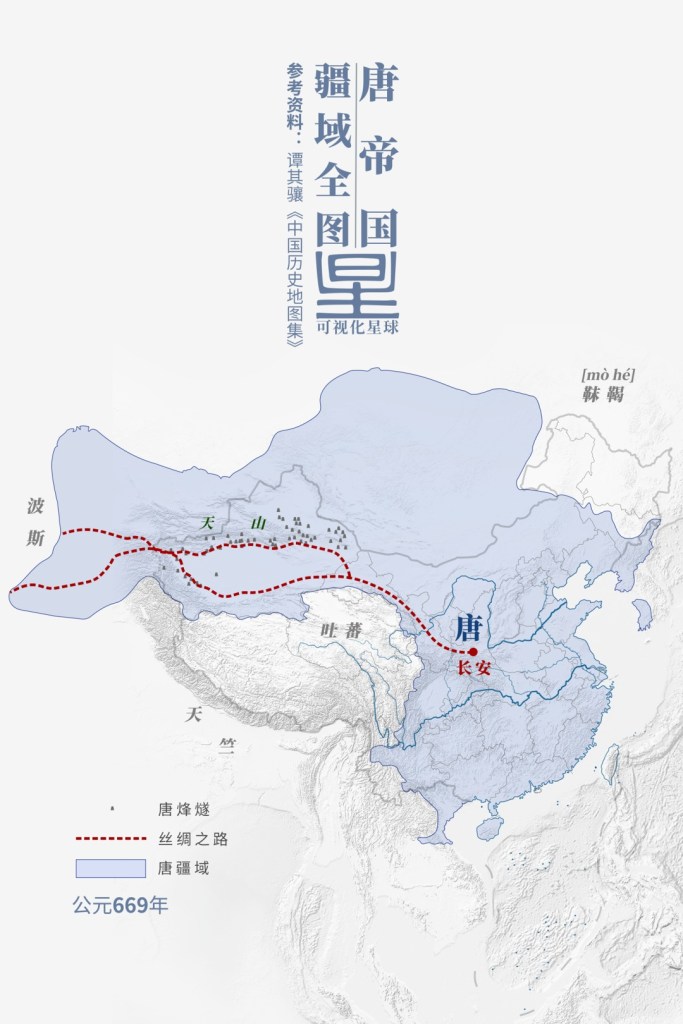

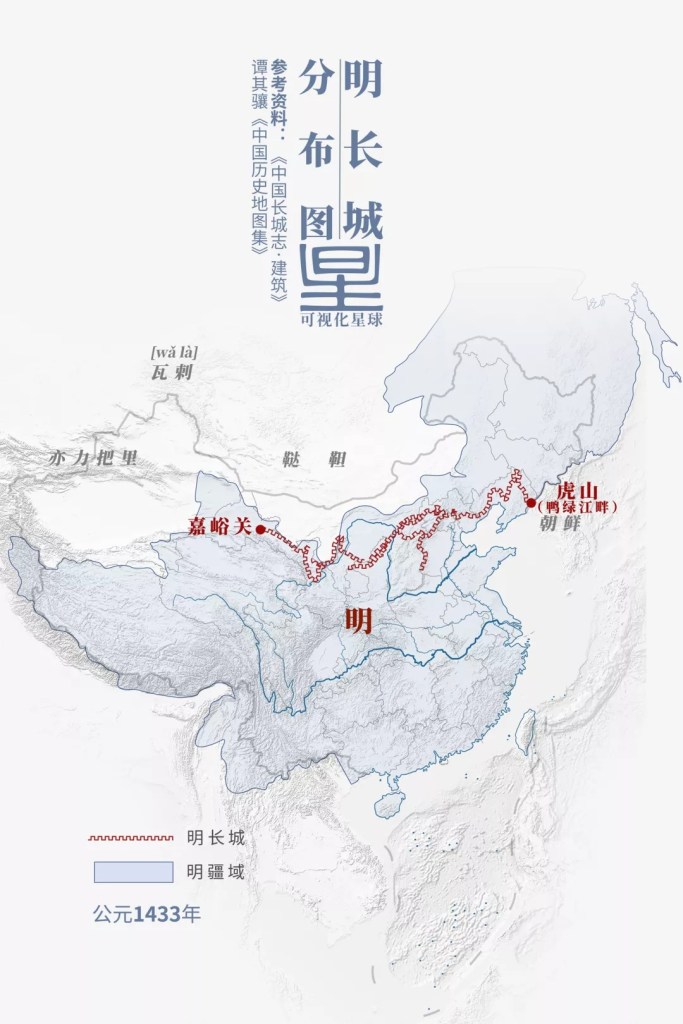

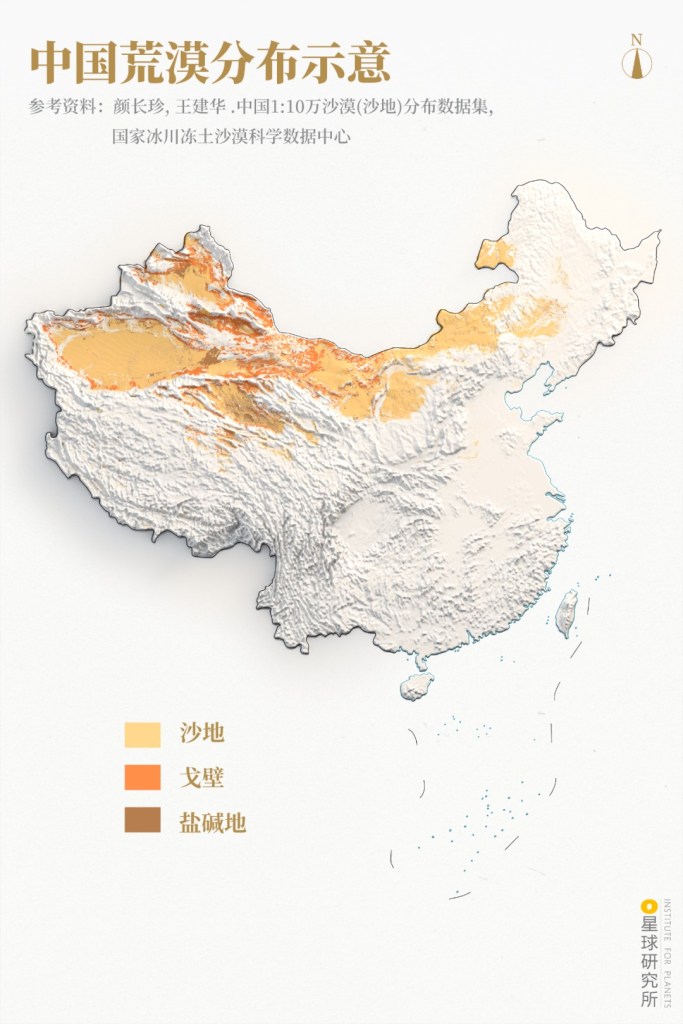

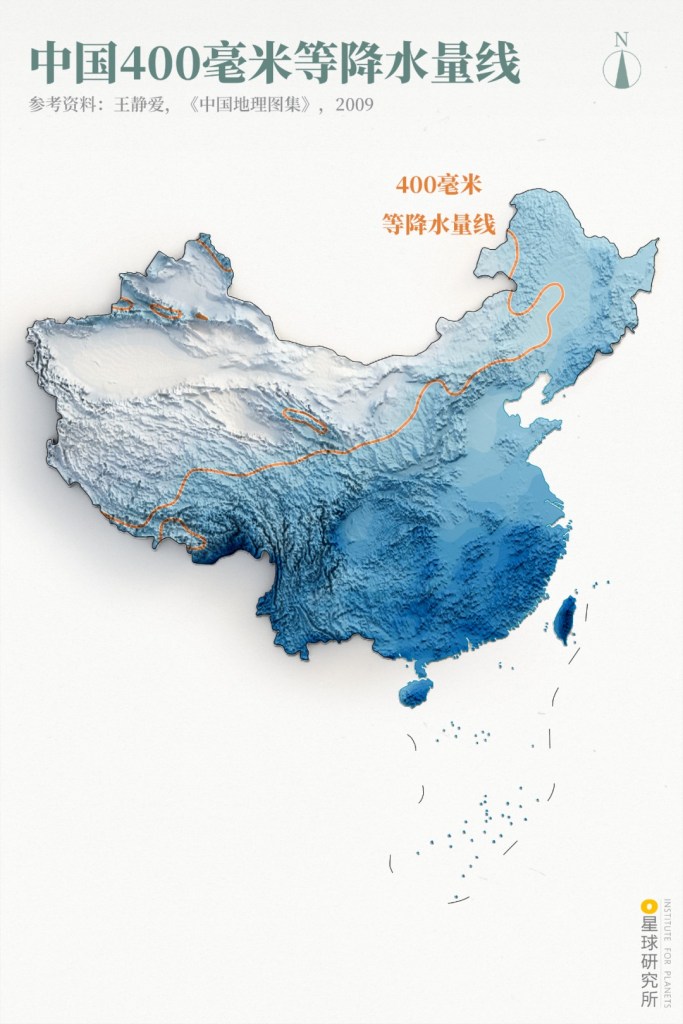

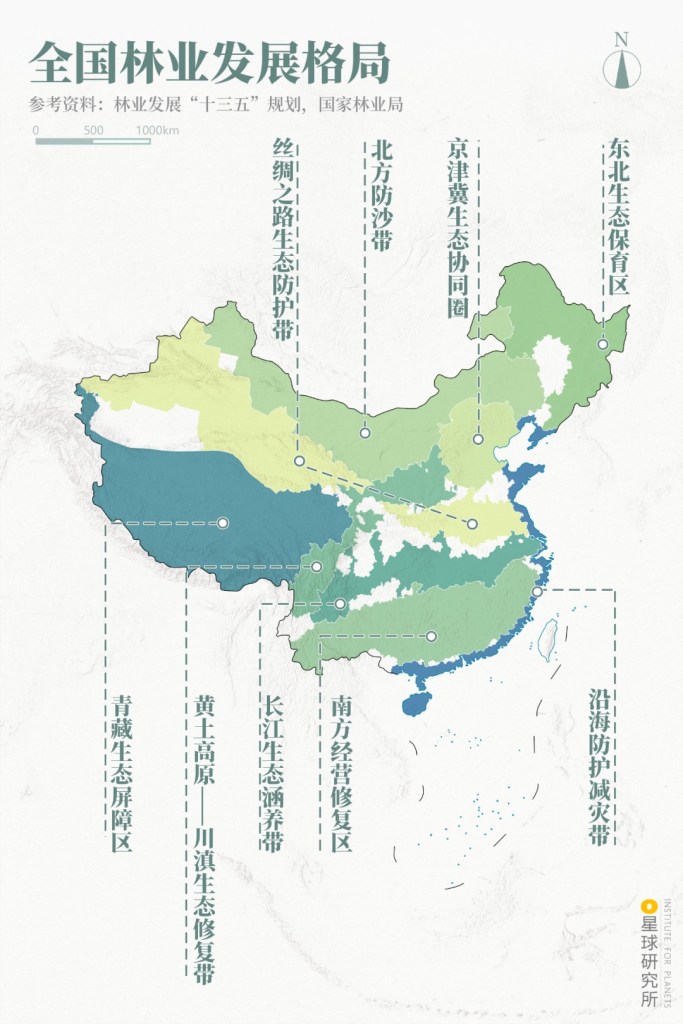

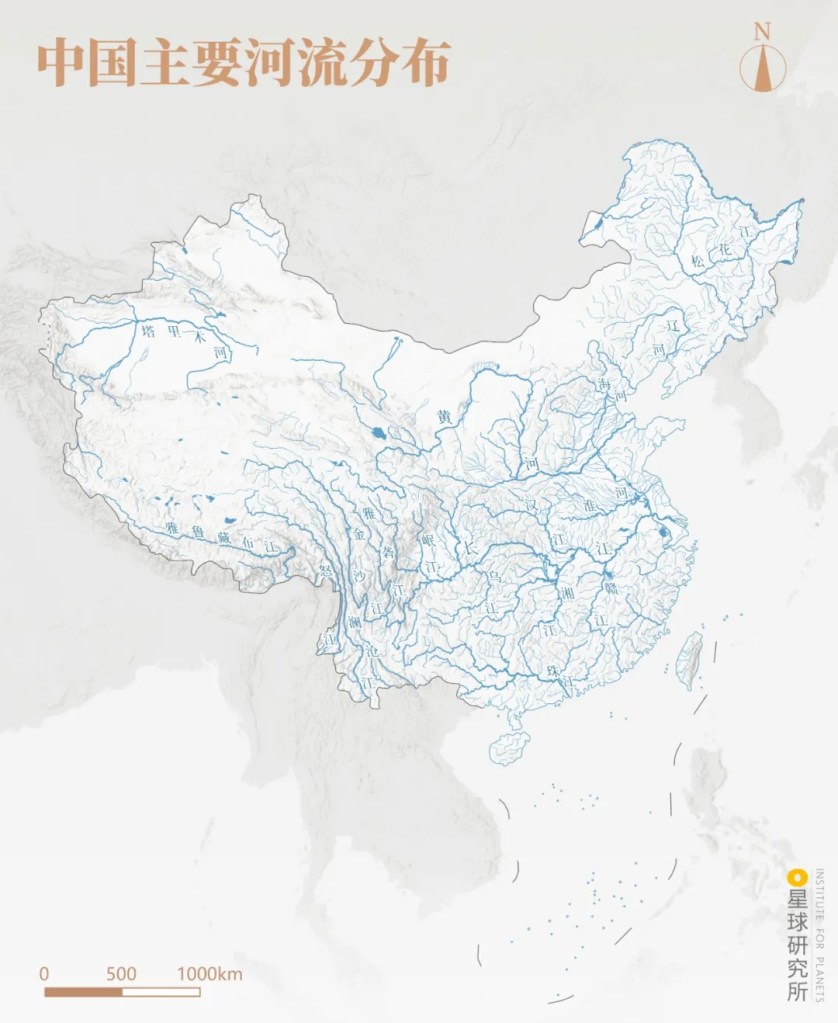

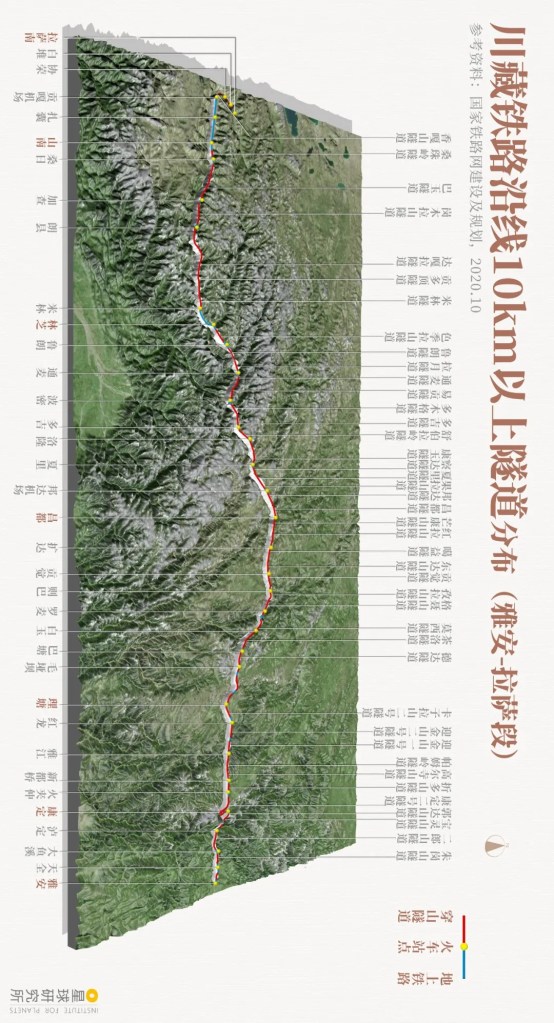

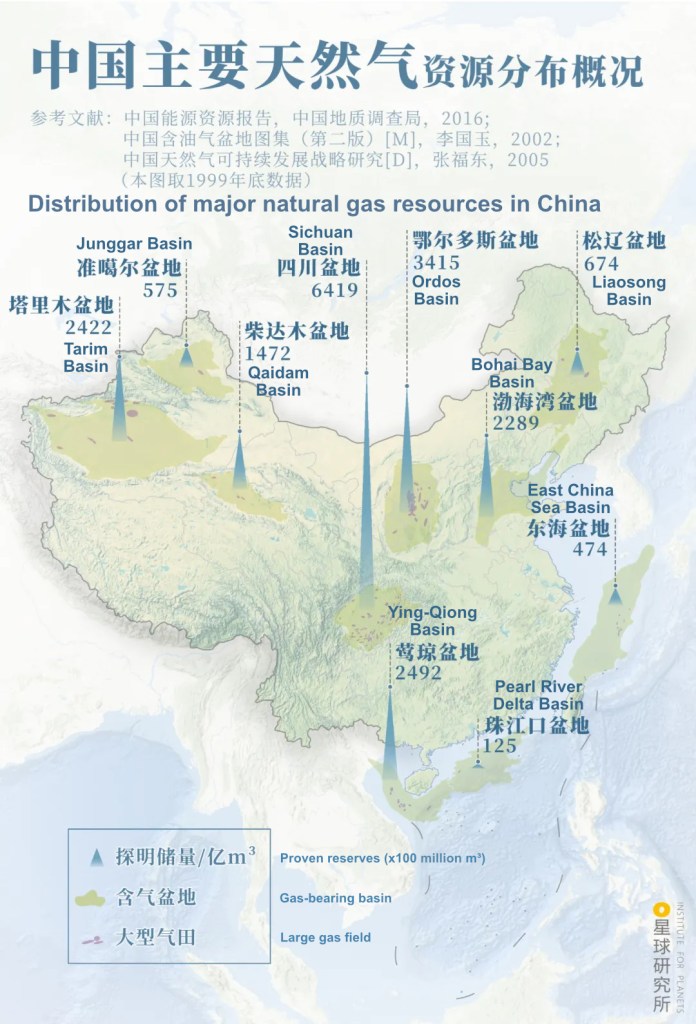

At the beginning of the 21st century, the total proven reserves below the vast land of China reached 2 trillion cubic metres. But 71% of these reserves are concentrated in a large number of sedimentary basins in the western regions.

(diagram: 陈志浩&杨宁, Institute for Planets)

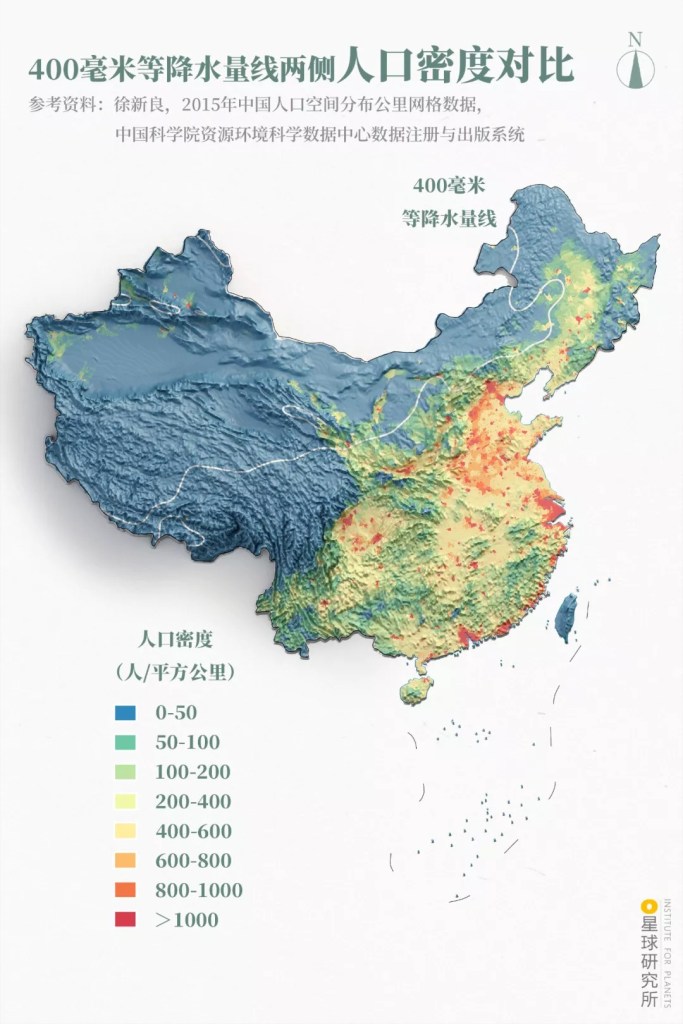

The eastern regions are quite on the contrary, there is little natural gas reserve here. Despite so, these regions are densely populated and economically developed, they consume much more energy and hence have a far greater demand for clean energy.

(diagram: 杨宁, Institute for Planets)

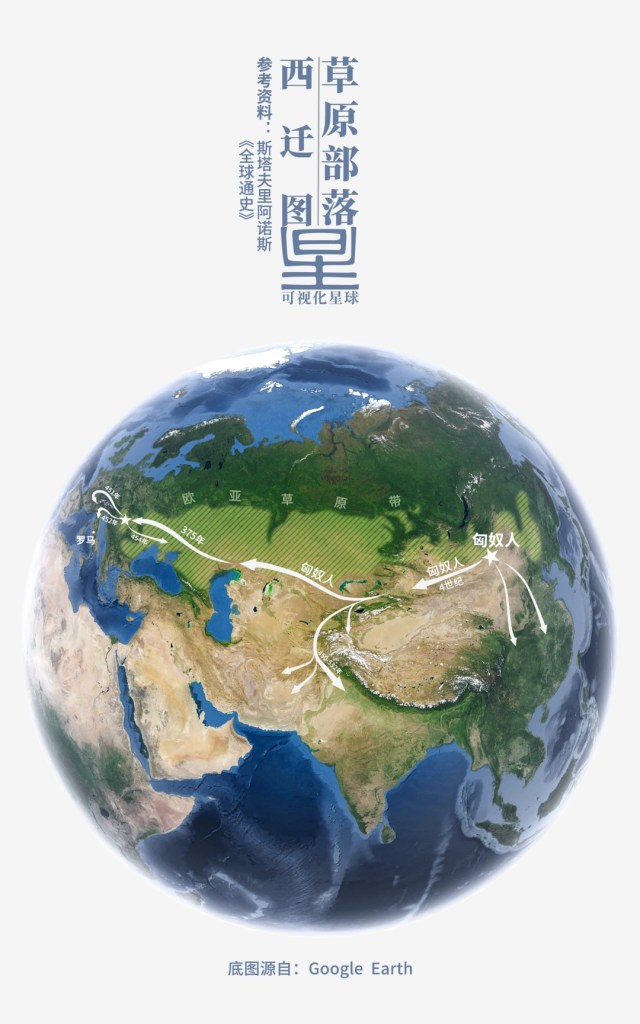

This results in a tough dilemma: resources are concentrated in the west and the demand is in the far east. To bridge the two, it is imperative to have in place an energy transportation system that can traverse across the large country.

3. West-East Gas Pipelines

The best way to transport gas is to use pipelines.

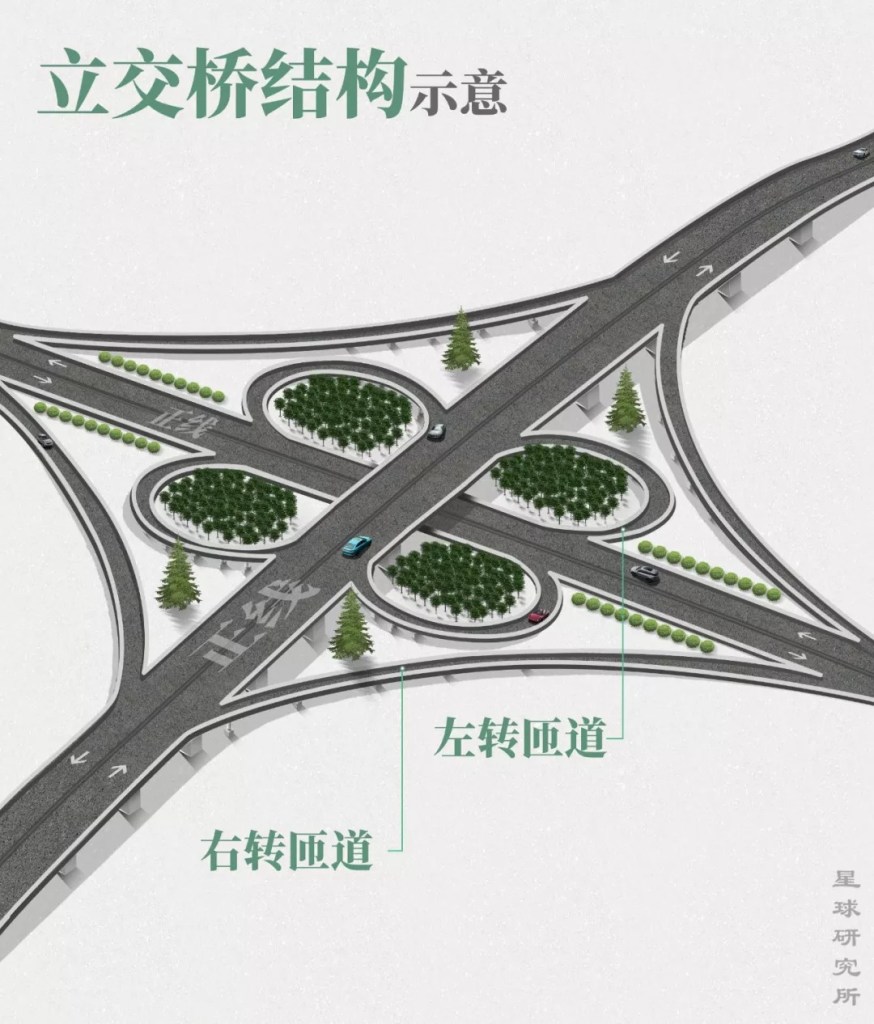

Unlike rail, highway or waterborne transport, once the pipelines are completed they can do the job nonstop all day and every day, with guaranteed efficiency and no concerns for the weather, hitting many birds with one stone.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

But laying a pipeline that stretches more than 4000 kilometres is much harder than it sounds. Besides, this has to be an integrated project which entails production, transportation and consumption of the natural gas. The estimated budget exceeded 1.2 trillion yuan, which is equivalent to 3.6 times the cost for Qinghai-Tibet Railway. This implies that we must have a sufficiently large reserve of the gas resource to make the project cost-effective.

This is also the reason why countless geologists had to travel deep into the barren Tarim Basin to conduct tedious surveying and drilling more than a decade before the project was even approved. The project just did not have the slimmest chance to succeed, at least not before the eventual discovery of 22 gas fields with a total proven reserve of natural gas reaching almost 5 trillion cubic metres.

(photo: 视觉中国)

After the discovery was made, arrays of derricks were erected across the barren desert and numerous drill pipes sent deep underground. As the roaring rigs ground through the rocks above the gas-bearing layers, natural gas locked deeply underground began to rush towards the surface when squeezed by formation pressure or artificial water injection.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

By 2005, there were enough gas fields operating in Tarim Basin to produce 12 billion cubic metres of natural gas a year, which accounted for 24% of the total production nationwide. But unearthing this enormous amount of natural gas leads to the next issue — transportation capacity. While natural gas flows out of the well naturally, it is far from realistic for the gas to rely on the momentum of this initial discharge to complete a several thousand kilometres journey. Therefore, engineers had to divide the pipelines into smaller segments and set up compressor stations at regular intervals to compress the gas and ensure a continuous movement.

(photo: 刘忠文)

In the actual planning, the pressure allowed inside the transmission pipelines is up to 10 MPa, which is 100 times the atmospheric pressure. This posed a huge challenge on the design strength and toughness of the building materials. Not only must they be able to withstand high pressure, but also have the largest diameter possible to achieve a higher transmission efficiency. All these were setting the bar extremely high for the construction.

After repeated experimentation and comprehensive evaluation of all potential designs, engineers finally came up with a domestically designed and manufactured construction material for the pipelines. This steel pipe, commonly referred to as model X70, fulfils all construction requirements encompassing strength, toughness and welding performance, while having a diameter of 1.016 metres. It set a new record for China’s gas pipeline production.

The X70 steel pipe was later upgraded to X80 with a diameter of 1.219 metres

(photo: 余海)

But building a pipeline stretching more than 4000 kilometres requires more than 300,000 segments of such steel pipes connected head to tail. This scale of production was truly unprecedented.

(photo: 吴胜波)

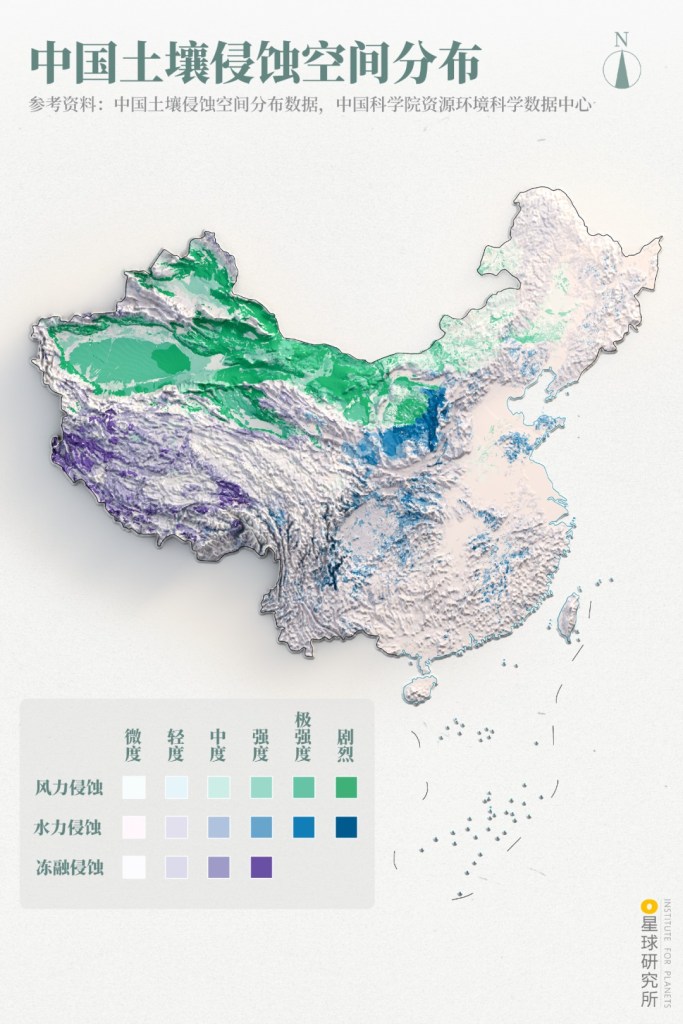

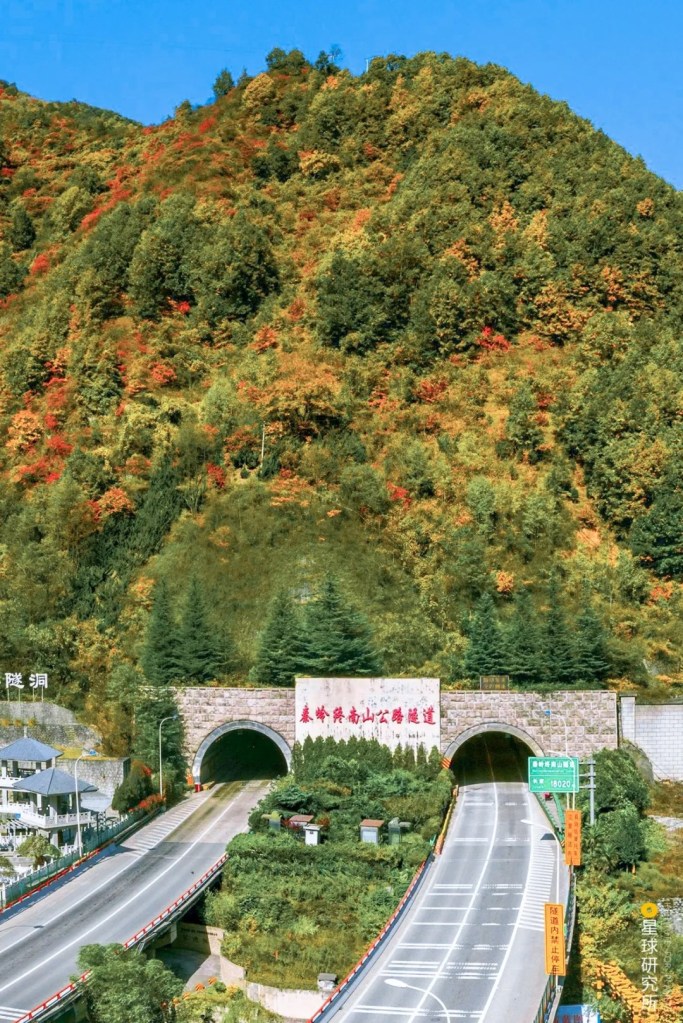

Furthermore, for this pipeline to travel across China it has to traverse mountains, plains, elaborate water networks, Gobi Desert and Loess Tableland. This means the builders must face extremely complex construction conditions.

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

Construction work was especially challenging in mountainous terrains, deserts and water networks which were not even connected with roads yet, so engineers really had to scratch their heads to create channels for steel pipe delivery to these remote zones.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

Once the steel pipes arrived at their destinations via those channels, they were assembled, welded together, patched and mended. Where necessary, they were even bent and adjusted to fit the local terrains.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

(photo: 余海)

Following that, builders just needed to excavate pipe trenches, lay the pipes and backfill the trenches.

(photo: 余海)

That sounds pretty straightforward. Conventional pipe laying methods would totally work if the builders were simply dealing with deserts, mountains and plains.

(photo: 赖宇宁)

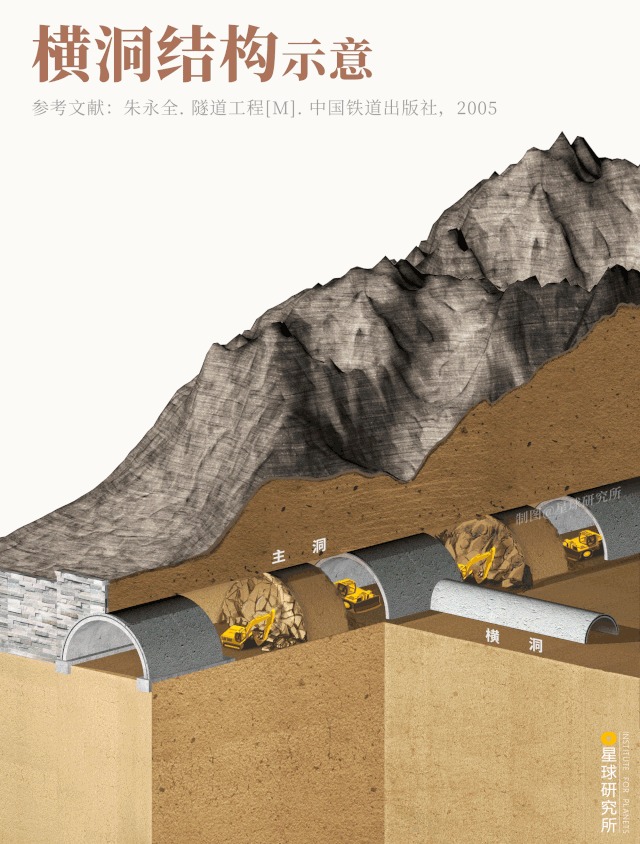

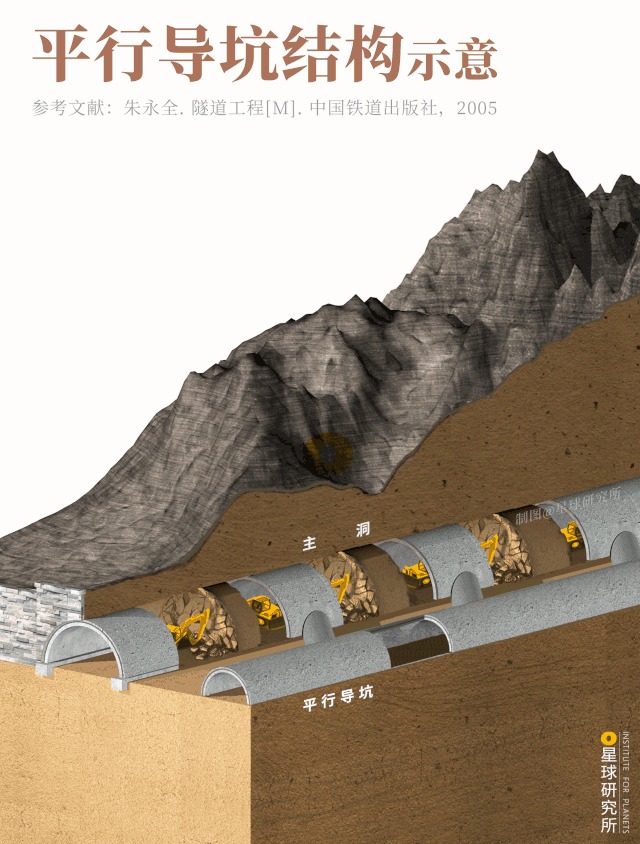

If only that were the case. In reality, the pipes have to travel across the Yellow River, Yangtze River and Huai River, as well as more than 1500 ditches and smaller rivers. The crude excavation approach was just not realistic, so the builders had to try something else. It could mean excavating a deeper tunnel beneath the rivers by the combined use of drilling and explosives…

(photo: 鲁全国)

…or opening up a guide channel under the rivers with a pilot drill bit and dragging back a reamer and pipe from the other side through the same channel.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

Alternatively, one can use a hydraulic jack to stuff concrete pipes into the river bed segment by segment and then insert the gas pipelines through them…

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

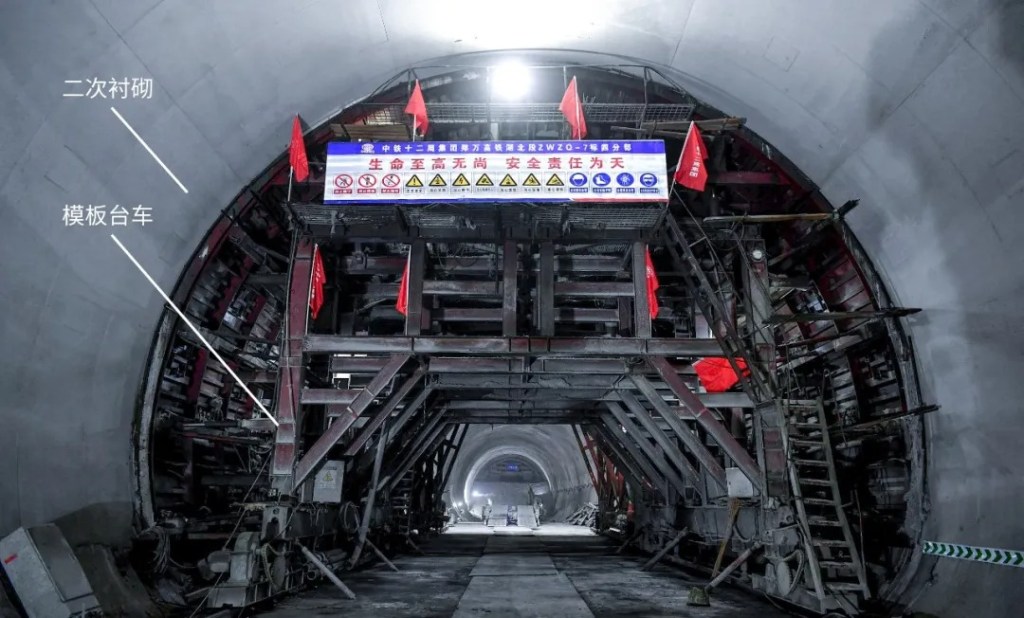

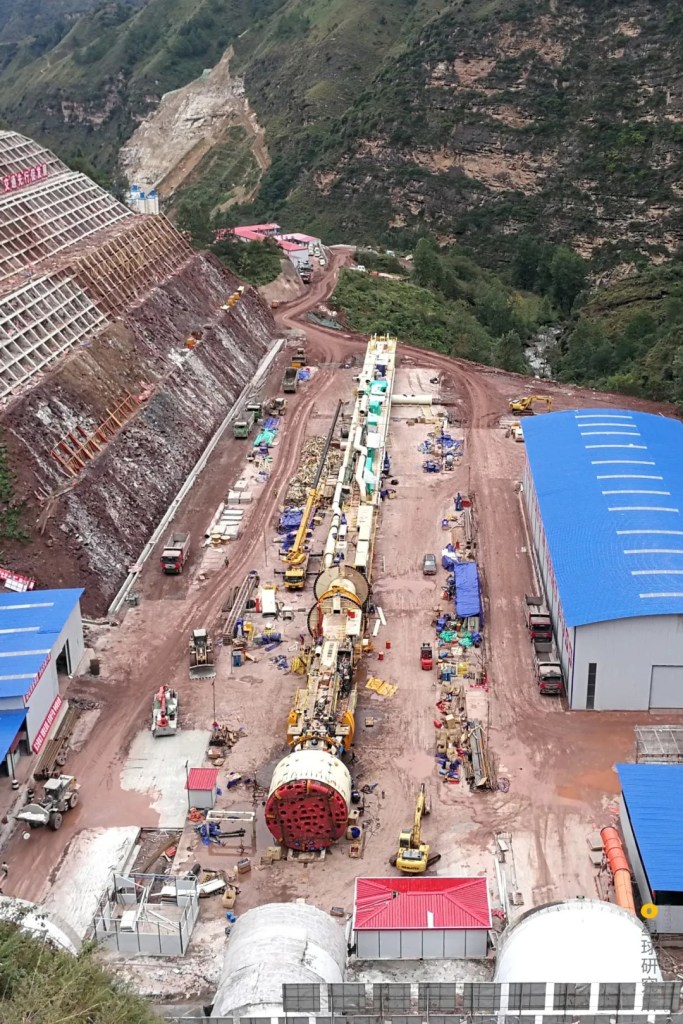

…or even excavate a proper tunnel 3.8 metres wide using a tunnel boring machine to make room for multiple pipelines.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

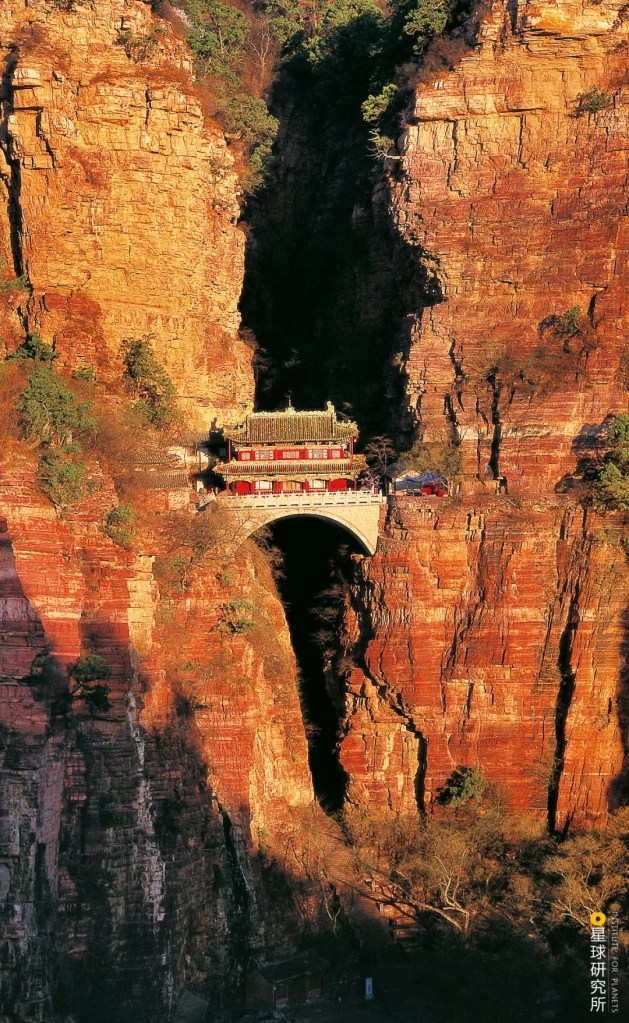

Where it is absolutely necessary to avoid a fault zone, engineers would simply give up on tunnels and let the pipelines fly across the river on a bridge.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

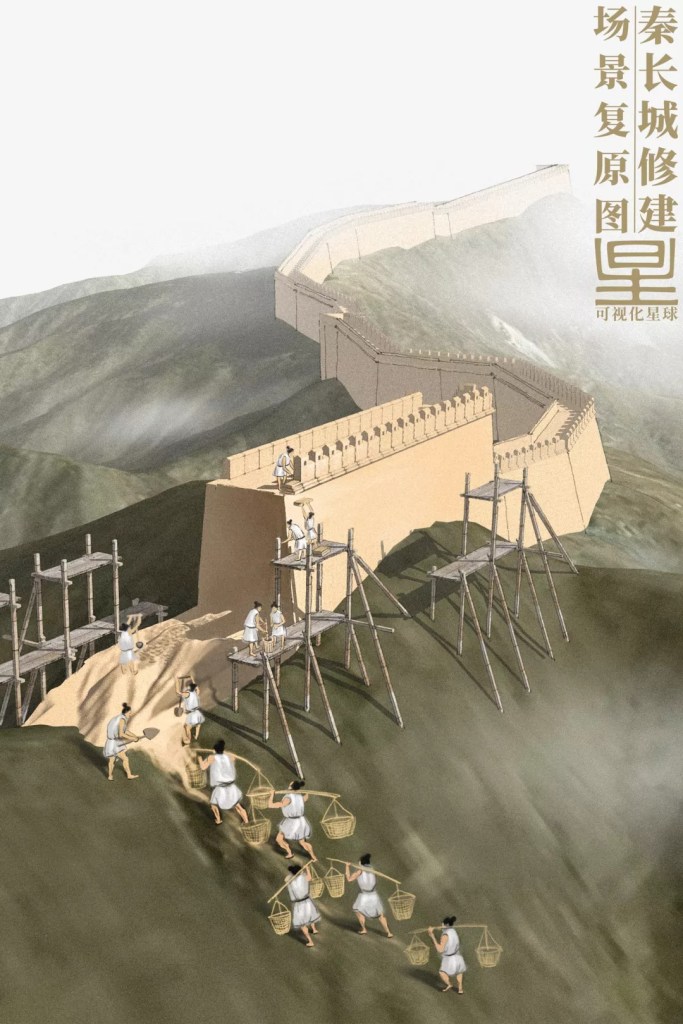

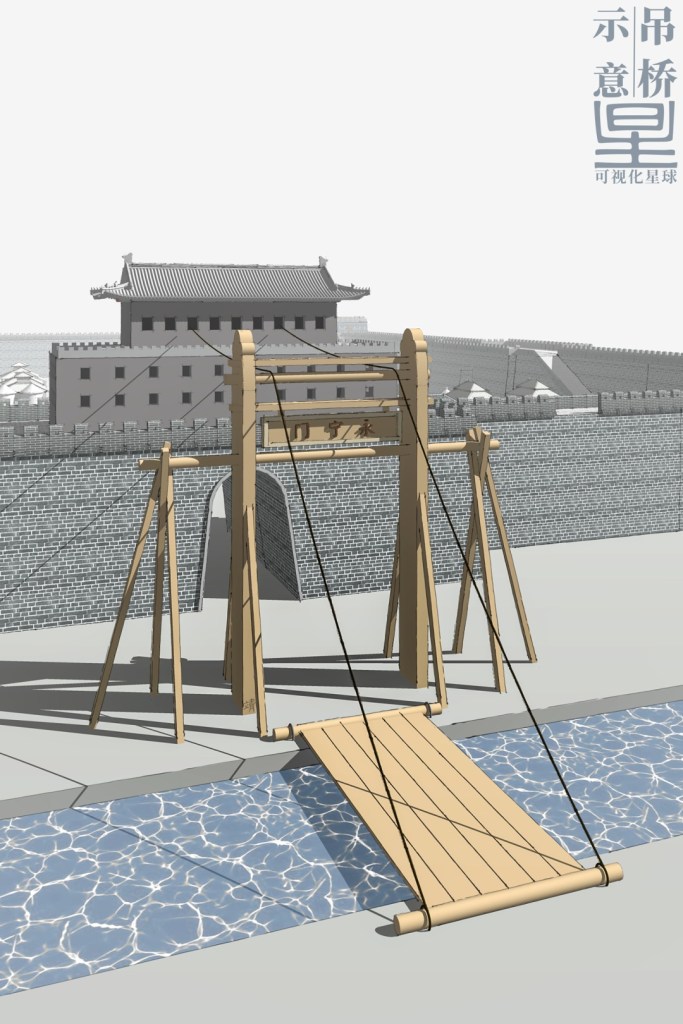

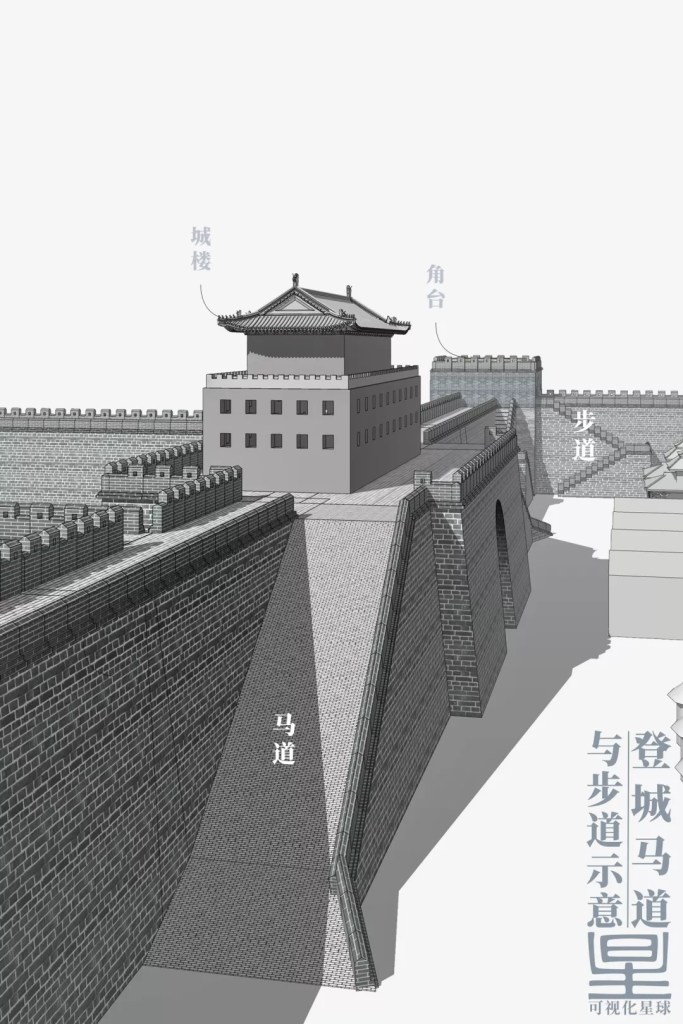

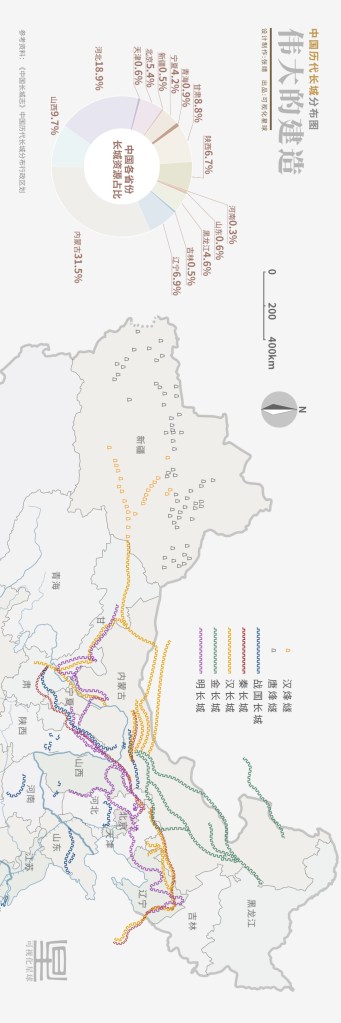

But natural barriers were merely part of the game. In order to minimise the impact on the surrounding environment, the construction work must also protect ancient ruins along the pipeline…

Pipe jacking method was used to traverse the Great Wall 12 times

(photo: 余海)

…and avoid conservation areas.

The construction had to change course whenever it went past conservation areas. These include the Lop Nur Wild Camel National Nature Reserve, Taihang Mountain Macaque National Nature Reserve and Anxi Hyper-arid Desert. For instance, the pipelines were rerouted 200 kilometres north when approaching the Lop Nur Nature Reserve.

(photo: 余海)

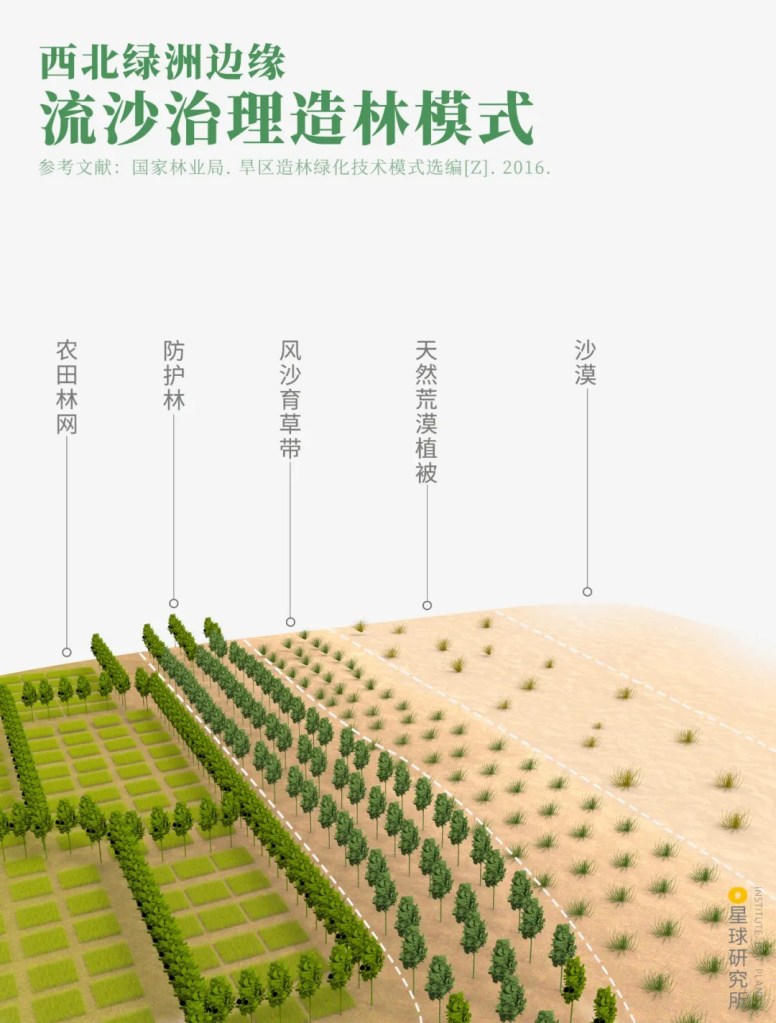

After passing through these ecologically fragile zones, the project still had to take care of the ecosystem by doing slope protection and even planting trees and grass.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

This is how the 4380-kilometres long natural gas pipeline — an energy artery that runs from the west end to the east end of China — was eventually completed. From then on, more than 12 billion cubic metres of natural gas flows out from the ancient strata underneath the deserts every year and embarks on a long journey via this giant artery.

12 billion cubic metres was the annual gas transportation capacity between 2004-2006. Since 2007, the capacity was increased to 17 billion cubic metres per year.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

The natural gas climbs mountains…

(photo: 余海)

…crosses valleys…

(photo: 余海)

…and travels through plains.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

It connects with additional gas fields along the way…

(photo: 许兆超)

…and finally enters thousands of households.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

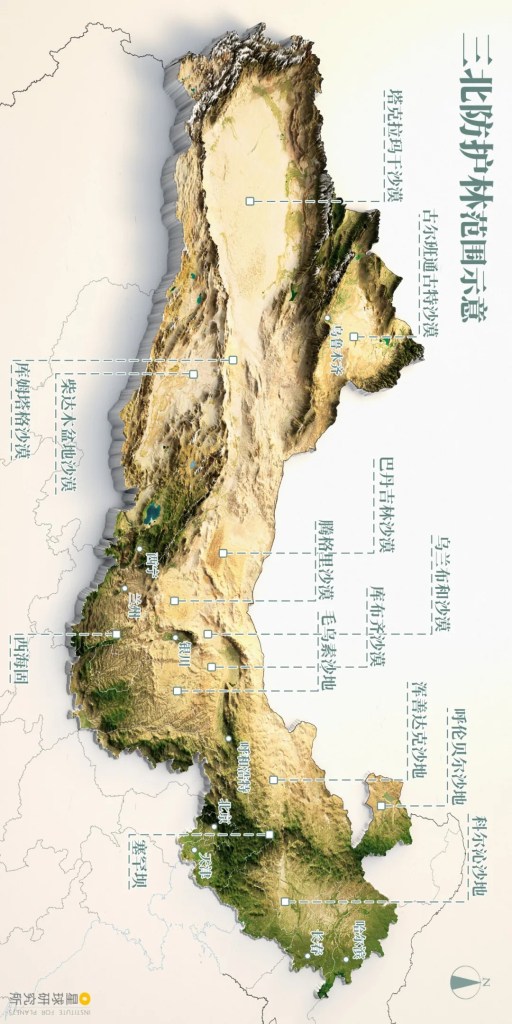

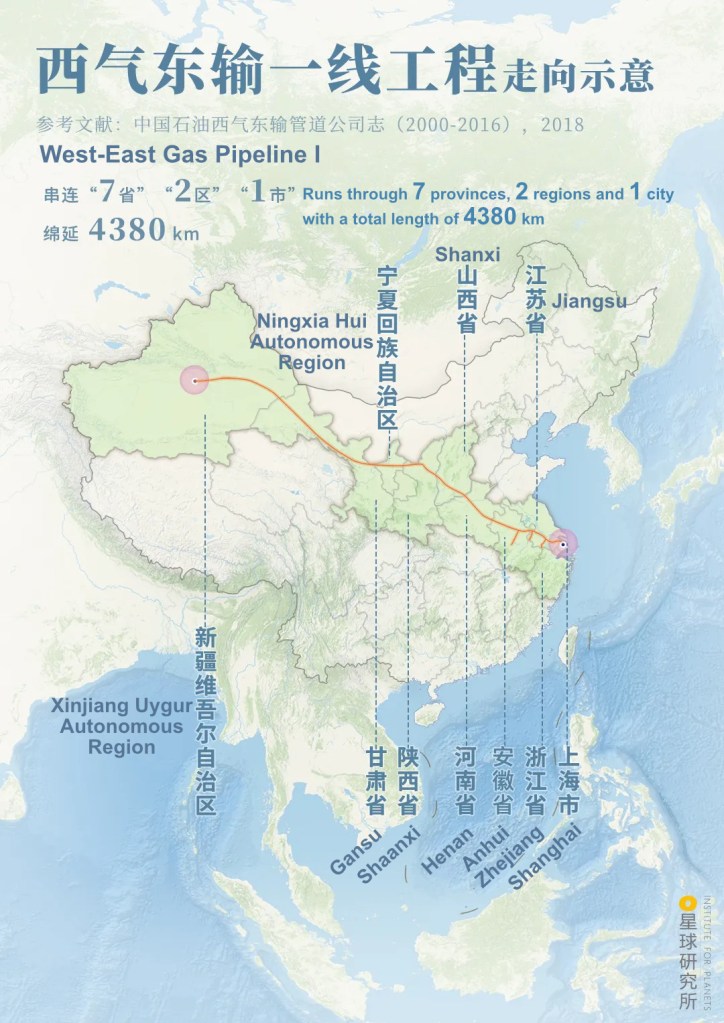

This is the West-East Gas Pipeline I, a mega project that encompasses gas hunting, production, transportation and utilisation. It starts from the Lunnan Gas Field in Xinjiang and finishes in Baihe Town in Shanghai, running through 7 provinces, 2 regions and 1 city across Gansu, Ningxia, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Henan, Anhui, Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces. Upon completion, this project immediately became the longest gas pipeline in China with the largest pipe diameter, highest transmission pressure and a superior transportation capacity, in spite of the most complex construction conditions it faced.

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

Despite the grand scale, this project is merely a drop in the ocean for the enormous demand for natural gas in China. We need more natural gas resource, and many more longer pipelines.

4. The mega network

Back in 1997, 5 years before the West-East Gas Pipeline I had commenced, the Shaanxi-Beijing Gas Pipeline connecting Ordos Basin and Beijing had already begun operation. Started off as a single pipeline, the project has since earned 3 more members and is now delivering cleaner energy to millions of households and enterprises via 4 different routes.

(photo: 余海)

And even more gas pipelines were commissioned after the completion of the West-East Gas Pipeline I, including the Sebei-Xining-Lanzhou Gas Pipeline that runs from Qaidam Basin to Lanzhou…

(photo: 国家管网集团官方微信)

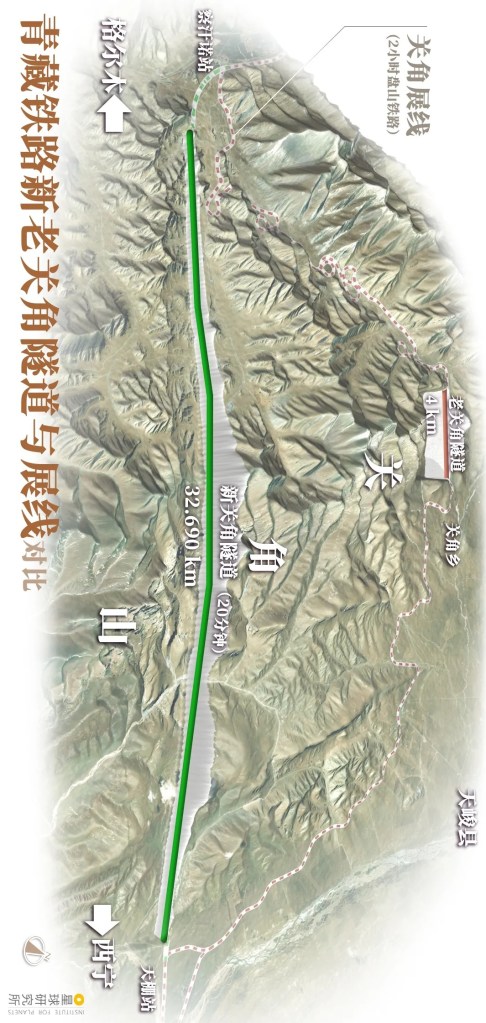

…the Zhong County-Wuhan Gas Pipeline and Sichuan-East China Gas Pipeline that connects the Sichuan Basin with Wuhan and Yangtze Delta, respectively…

Sichuan-East China Gas Pipeline travels from Dazhou in Sichuan to Shanghai

(photo: 史垒)

…and the Zhongwei-Guiyang Gas Pipeline which combines the Sichuan-Chongqing Gas Pipeline Network and West-East Gas Pipeline.

(photo: 国家管网集团官方微信)

Thanks to these projects, gas fields all over China are now linked up by interconnected pipelines, which tirelessly deliver natural gas from central and western China to the densely populated and highly industrialised regions, thereby contributing to a cleaner path towards development of the country.

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

At the same time, the number of proven reserves and production are both increasing by the day. In particular, the extraction of unconventional natural gas is gaining a lot of traction. For instance, even though shale gas extraction was only commercialised in 2013 in China, the annual production by 2020 had already hit the 20 billion cubic metres mark, accounting for 10% of the total natural gas production in the entire country.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Meanwhile, the rapidly developing China kept on raising its demand for energy. A gap between the production and consumption of domestically produced natural gas first appeared in 2007 and had since continued to enlarge.

(diagram: 杨宁, Institute for Planets)

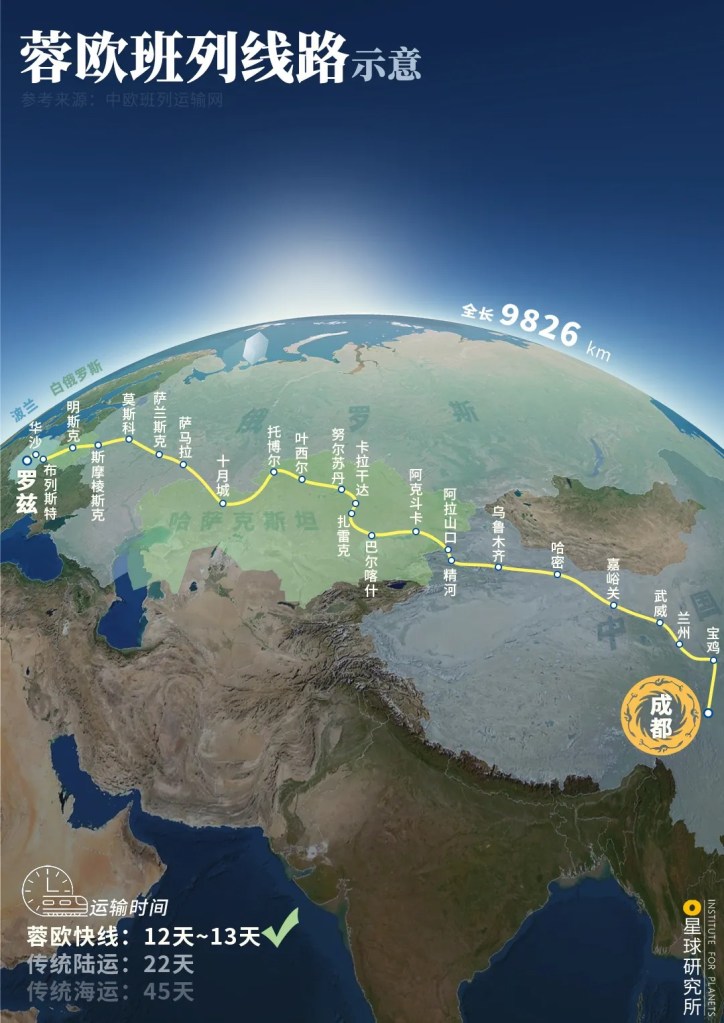

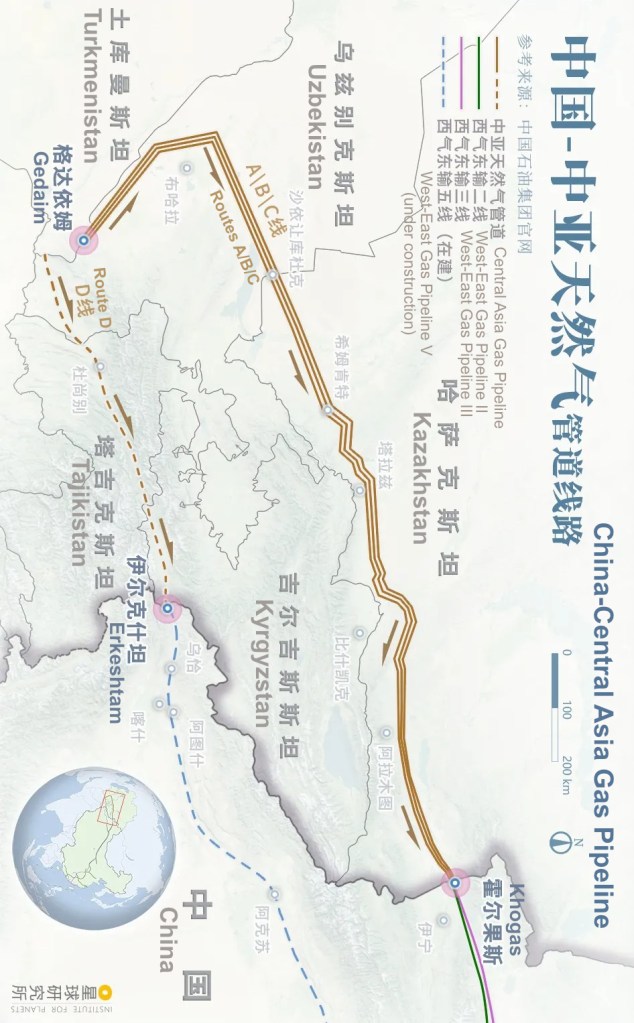

In other words, China was unable to produce enough natural gas it needs, so it needed to look elsewhere abroad for more. Consequently, longer and larger gas pipelines began to appear across the vast Eurasian continent one after another, including the 7000-kilometres China-Central Asia Gas Pipeline which runs through Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan before entering China, after which it unites with the West-East Gas Pipeline II and III to deliver the natural gas from Central Asia all the way to eastern China. Its annual gas transportation volume is almost 5 times that of West-East Gas Pipeline I.

Routes A, B and C have been completed

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

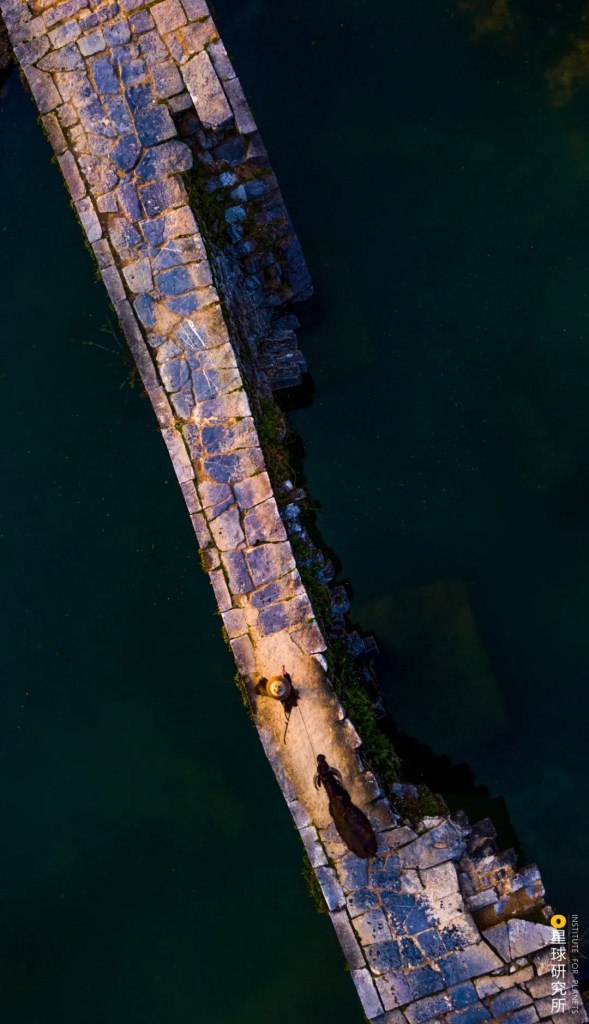

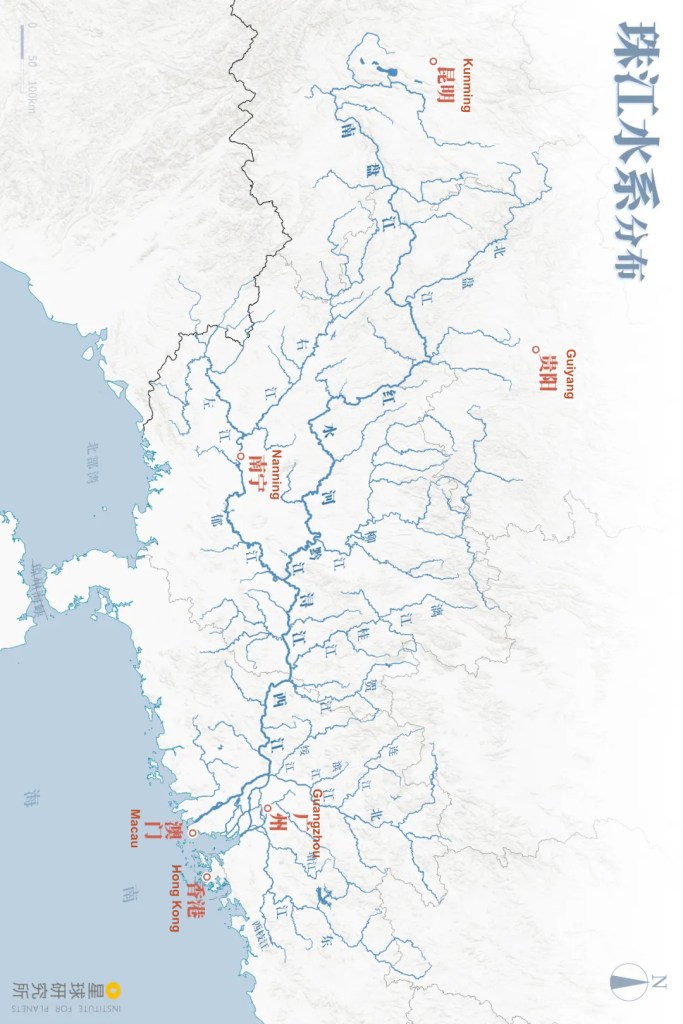

The 7600-kilometres Sino-Myanmar Gas Pipeline runs between Myanmar and China. Every year, it delivers 12 billion cubic metres of natural gas produced in the Bay of Bengal to southwestern provinces in China, including Yunnan, Guizhou and Guangxi, via a direct land route. This is equivalent to building an extra West-East Gas Pipeline I for the southwest region.

The gas pipeline crosses the river on a suspension bridge with a span of 280 metres

(photo: 赵子忠)

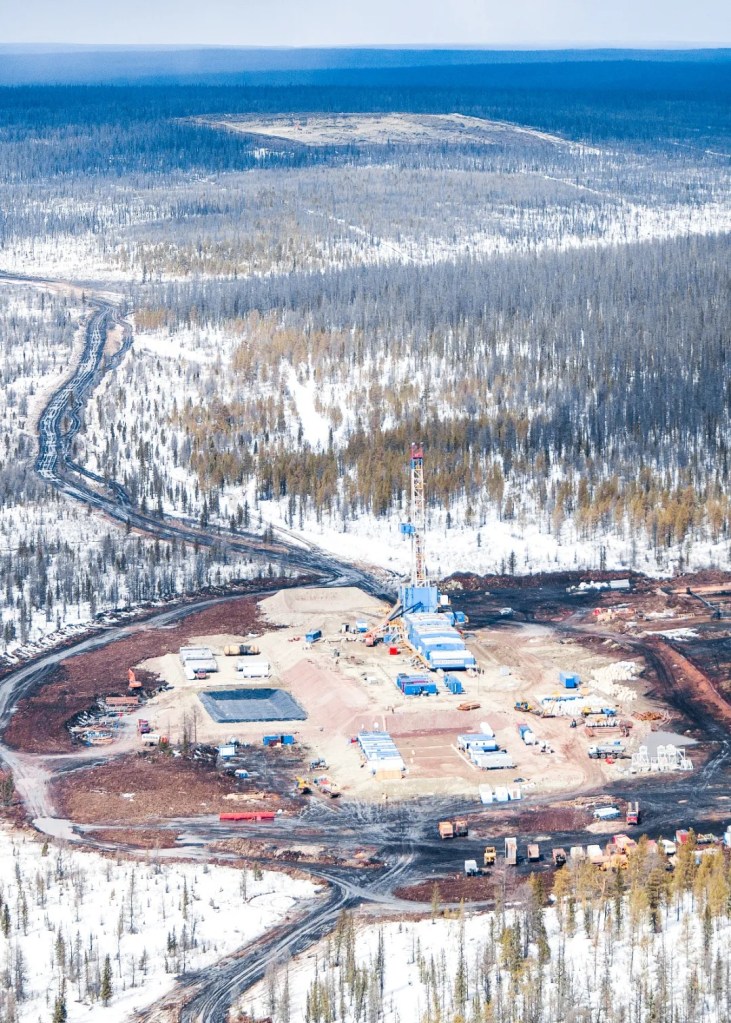

There is also the China-Russia East Route Gas Pipeline measuring 8111 kilometres in total. This pipeline is currently the longest gas pipeline with the largest single-tube gas transmission volume. It begins in eastern Siberia and enters China through the Amur River, then runs south towards the Yangtze Delta. Once it is completed and becomes fully operational, the annual gas transportation volume will reach up to 3.2 times that of the West-East Gas Pipeline.

The section between Amur River in Heilongjiang and Yongqing in Hebei is now completed

(photo: 国家管网集团官方微信)

Nevertheless, even when all these multinational gas pipelines are completed, the natural gas coming through them will only account for 38% of China’s total import of natural gas. The bigger portion will come from across the ocean. Unlike pipeline gas, natural gas of this kind will be purified and condensed into liquefied natural gas (LNG) and be shipped from countries like Australia and Malaysia to China on specialised LNG carriers. It will then be unloaded at LNG receiving terminals, stored and regasified before being distributed into the pipeline network in China.

(photo: 卢志峰)

Ever since the commission of the first LNG receiving terminal in Guangdong in 2006, there have been 22 other receiving terminals erected along the coastal line. The amount of natural gas received at these terminals every year is comparable to 7 years of consumption in Beijing.

(diagram: 陈志浩&杨宁, Institute for Planets)

In addition, the natural space available within gas fields have been utilised to set up large-scale underground gas storages. During the off-season period (summer and autumn), surplus pipeline gas will be injected into these storages until the next peak season. In Beijing, for example, about 40-50% of winter gas usage comes from such storages.

(photo: 国家管网集团西气东输公司)

As of today, there are as many as 27 underground gas storages in China which can together store more than 10 billion cubic metres of gas, enough to sustain 300 million people for one whole year.

(diagram: 陈志浩&杨宁, Institute for Planets)

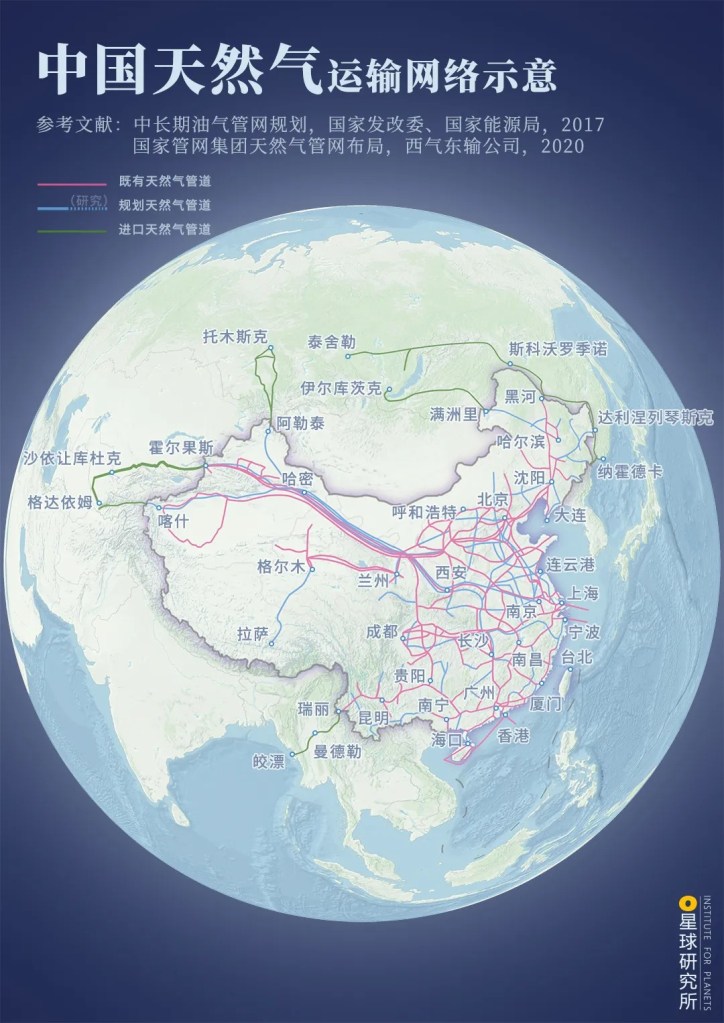

As such, this arduous project is no longer a solo play by the West-East Gas Pipeline, but a grand orchestra composed of 4 sizeable import channels taking care of business coming from all cardinal directions, as well as 87,000 kilometres of criss-crossing pipelines and 27 underground gas storage that are always on standby. This is truly a multinational and ever-improving mega gas network.

Now that this network is in place, in every year to come there will be on average more than 200 billion cubic metres of natural gas produced in various regions and gas fields and transported thousands of miles through all geographical barriers to reach millions of households and fuel the livelihood of 400 million Chinese people. It will be the indispensable leg for China to keep dashing forward.

Red: operating pipelines

Blue: planned pipelines

Green: import pipelines

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

But this by no means implies we can just sit back and relax. With the constantly rising import volume, China’s natural gas external dependency is already hitting 43%. Unknown factors like supply disruption and price fluctuations are but some of the significant risks we are facing.

Nonetheless, a reform in energy structure is a long and painful path that can never be finished within a day or two. There is no magic to it, nor can we just sit around and expect others to give a hand. The only way forward is to continue developing our own scientific knowledge and technologies, which has been instrumental in the recent discovery of the 21 hundred-billion-cubic-metre gas fields over the past decade.

(photo: 余海)

Owing to technological advancement, our pipeline clusters are beginning to merge into a larger, interconnected one. From abroad to within China, from pipeline gas to LNG, our different natural gas resources are complementing each other. The “one-network-for-all” configuration is slowing taking shape.

(photo: 管道互联互通工程)

Also because of technological advancement, we are able to simultaneously develop other clean energies including hydro, wind, nuclear and solar power. Together with natural gas, they pushed the coal consumption proportion down from 68% in 2002 to 57% in 2019.

(diagram: 杨宁, Institute for Planets)

The future may still be a bumpy ride for us, but we shall stay on and move on along this path until we can finally see the clean, sustainable tomorrow by our own eyes.

(photo: 余海)

Production Team

Text: 艾蓝星

Editing: 桢公子

Photos: 昼眠

Maps: 陈志浩

Design: 罗梓涵&杨宁

Review: 张照&云舞空城&雪梨

Expert review

Hu Qihui, lecturer at China University of Petroleum (Huadong)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the National Pipeline Network Group West-East Gas Pipeline Company for providing photos and immense support for content review.

References

[1] 《西气东输工程志》编委会. 西气东输工程志[M]. 石油工业出版社, 2012.

[2] 何利民等. 油气储运工程施工[M]. 石油工业出版社, 2007.

[3] 西气东输(2002-2013)企业社会责任专题报告.

[4] 陈利顶等. 西气东输工程沿线生态系统评价与生态安全[M]. 科学出版社, 2006.

[5] 历年中国天然气发展报告.

[6] 历年中国环境状况公报.

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光