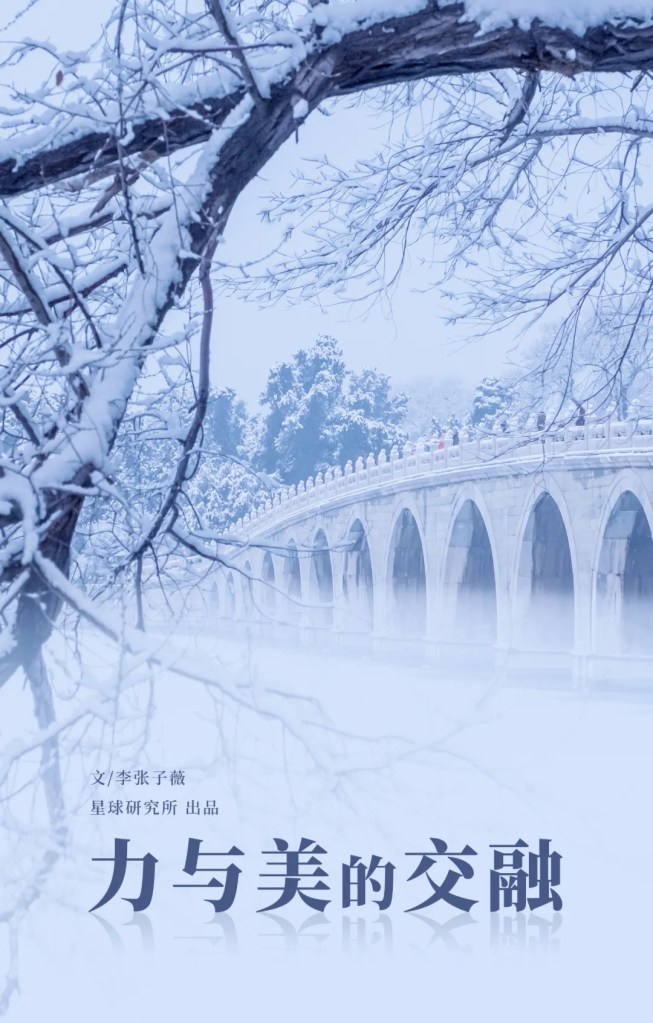

Original piece: 《中国古桥,有多美?》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 李张子薇

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

What paints the familiar impression of an ancient China?

It is the blushing walls and ebony tiles,

the protruding cornices and curling eaves,

and the lady with an oil-paper umbrella strolling over a bendy bridge.

…

It may be the serene bridge leaning by the ripples with a watery makeup…

(photo: 沈欣洪)

…or the enchanting rainbow brushing lips against the stream.

(photo: 胡寒)

On this aged yet vigorous land of China, ancient bridges continue to dance like “rainbows”, “jade belts” or the “crescent”, still striking the hearts of tens of thousands with their magical reflections in the glittering waters.

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

Bridges do not just exist to let us gather and communicate in the real world, they create a poetic realm that fascinates.

One may find in this realm a moment of reverie…

你站在桥上看风景,看风景的人在楼上看你

On the bridge you stand viewing the sight,

卞之琳《断章》

yourself beheld by a scenery admirer from height.

Fragments by Bian Zhilin

(photo: 王昆远)

…a state of melancholy…

枯藤老树昏鸦,小桥流水人家

Withered vine, gnarled trees, drowsy crows;

马致远《天净沙·秋思》

narrow bridges, quiet brooks, rustic cottages.

Heaven-pure Sand: Autumn Thoughts by Ma Zhiyuan

(photo: 非渔)

…and the scent of love.

柔情似水,佳期如梦,忍顾鹊桥归路

Love is tender as water but reunion is faraway like illusion, the farewell sight on Magpie Bridge is unbearable.

秦观《鹊桥仙·纤云弄巧》

Immortals of the Magpie Bridge: Intricate Forms of Clouds by Qin Guan

(photo: 刘珠明)

This tenderness of ancient bridges in the southern misty rains has been nourishing the spiritual world of Chinese people, and we shall now unveil the magnificent beauty of Chinese ancient bridges.

1. Origination of ancient bridges

Bridges connect. Being a “path in the air”, all they have to do is to link up the two banks they stand on.

(photo: 李力群)

For this purpose, bridges adopt diverse appearances in different natural environments.

In southwest China, ropes or metal chains hanging across the deep valleys and raging torrents are the best tools to cross a river. To do so, one simply needs to cling onto the suspended cable and slide along it. This is the zip-wire bridge (索桥).

(photo: 芮京)

Where currents are more calm, people bundle up boats in a line to reach the opposite bank. These bridges supported by buoyancy are known as pontoons (浮桥).

This bridge was first built as a pontoon in 1171 during the Southern Song dynasty. Today it is a pontoon-beam bridge complex, where the pontoon section can be opened up to allow passage of large ships

(photo: 林宇先)

Even before the advent of steel and concrete, pontoons were capable of forging a path for pedestrians across the giant rivers in China including the Yangtze River and Yellow River.

These pontoons do not exist any more

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

The forms of bridges also change accordingly as rivers with vast surface and deep channels constrict into rivulets and brooks. Instead of having pontoons and zip wires, beams are more popularly used as the major structural support for bridges here. Some make use of a log of wood, others lay down a piece of rock. These are the beam bridges (梁桥).

(photo: 赵永清)

Compared to hard rocks, timber is easier to process and therefore became the most favourable construction material for bridges in ancient times. Our ancestors used mortise and tenon joints to assemble timber and construct wooden beam and pier bridges (木梁木柱桥).

Some of these bridges are supported by upright wooden pillars (木柱) as they take shelter in the thick woods.

(photo: 陈俊宇)

Others stand on slanted wooden pillars while lighting up the tranquil village with flickering night lamps.

Completed during the Ming dynasty, it is a classic slanted-pillar bridge

(photo: 卢文)

Wood, however, decays in water over time. Therefore, our ancestors switched to using stones to build more durable bridge pillars and created the stone pier-wooden beam bridges (石墩木梁桥). Since the Iron Age, they made remarkable breakthroughs in pile foundation technologies using ironware and stone in conjunction, which helped them nail the pillars firmly into the ground.

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

In order to stabilise these stone pier bridges in rivers, builders started constructing the piers with the shape of a boat, so that their pointy front can divert the impact of flowing water and strengthen the structure.

Built during Southern Song dynasty, the bridge was partially damaged by the flood this year

(photo: 王毅)

And to increase the span of wooden beam bridges on these stabilised stone piers, builders created stacked wooden structures that stick out like an arm with extended interdigitating members. These are called cantilever beam bridges (伸臂梁桥).

In longer bridges, one may see such cantilever arms sticking out from both sides of the piers like a giant dougong (斗拱, interlocking wooden block and bracket) to support the bridge beam.

It was built during the Qing dynasty

(photo: 刘艳晖)

In shorter ones that do not need piers, these cantilevers “grow” out from the river banks, either horizontally…

(photo: 吴卫平)

…or with an angle.

(photo: 吴卫平)

Apart from cantilevers, slanted supporting frames can also do the job.

(photo: 吴卫平)

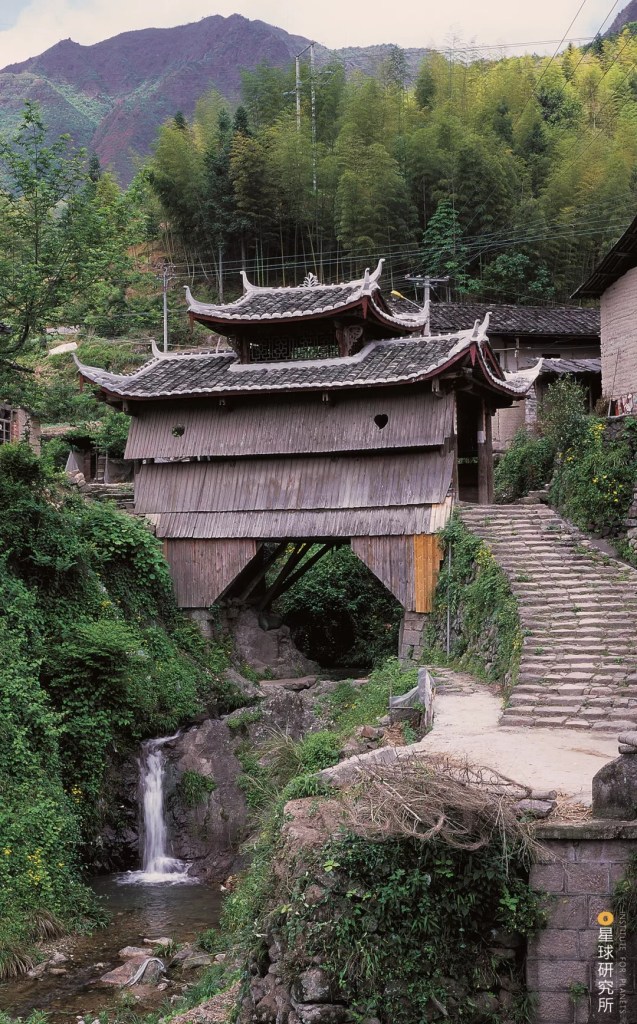

There is a unique member within the family of Chinese wooden bridges known as wooden arch bridge (木拱桥). It is tightly woven by multiple timber elements that are intersecting perpendicularly or in parallel.

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

Until the 1970s it was still firmly believed that the technology for building such bridges had been lost and one could only reminisce about their elegance in the classic painting Along the River During Qingming Festival, but in fact, wooden arch bridges are pretty much alive and actively used across China.

It was built during the Ming dynasty

(photo: 吴卫平)

The Santiao Bridge in Taishun, Zhejiang, Gongxin Bridge in Gutian, Fujian, and Baling Bridge in Weiyuan, Gansu, are all famous members of the wooden arch bridge family.

(photo: 林祖贤)

The force structure and construction techniques of these bridges follow the same architectural style of the Bianshui Rainbow Bridge illustrated in Along the River During Qingming Festival.

(photo: 吴卫平)

From wooden beam and pier bridges to stone pier-wooden beam bridges, and from cantilever bridges to wooden arch bridges, wooden bridges in ancient China had really explored every form possible. But due to the inherent characteristics of timber, their force structure was hitting a developmental ceiling and their diversity was plateauing off. Fortunately, this was around the same period when stone bridges began to emerge, which would then go hand in hand with wooden bridges to become the staple of Chinese bridges for the next thousands of years.

2. Stone bridges in the misty rains

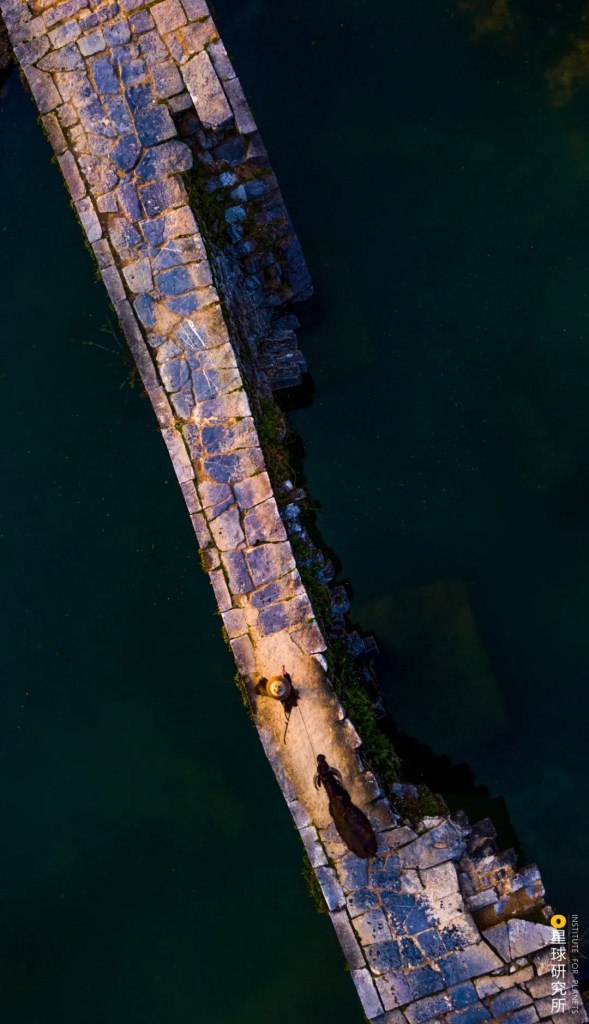

As wooden bridges became widespread across ancient China, wooden beams on stone piers were gradually replaced with stone beams to build stone pier-stone beam bridges (石墩石梁桥). Stone beam bridges are usually straight as this makes them technically easier to build. They border the picturesque landscape and its mirror image almost like a dragon gliding on water.

(photo: 赵永清)

There are nonetheless other forms of stone bridge that also make a perfect touristic landmark with multiple twists in the structure.

(photo: 石天金)

Where boats needed to pass through, builders would elevate the entire main span to make way.

(photo: 胡寒)

Stone beam bridges display highly advanced construction technology and impressive spans never seen before their era, thanks to the exclusive use of stones guided by our ancestors’ wisdom and meticulous skills.

Luoyang Bridge, the oldest sea-crossing bridge in China, is also a stone beam bridge. It stands out because of the technology used to build it. When the bridge piers were completed, builders started to cultivate oysters around the foundation submerged in water. This allowed the colloidal body fluid secreted by the oysters to glue the stones together and stabilise the bridge foundation, a technique way ahead of its time around the globe.

It was completed in Northern Song dynasty

(photo: 雾雨川)

Anping Bridge, the longest existing ancient bridge in China, is also a stone beam bridge. Stretching 2255 metres across, it is 2.25 times as long as the Luoyang Bridge, and hence was praised as the “bridge with unmatched length under heaven (天下无桥长此桥)”. The bridge was so long that the builders actually built 5 pavilions along it so that pedestrians may take a rest from the lengthy walk. As a Qing poet had beautifully described,

白玉长堤路,乌篷小画船

A long embankment road of white jade,

a little sailing boat with black awning.

It was completed in Southern Song dynasty

(photo: 姜青芳)

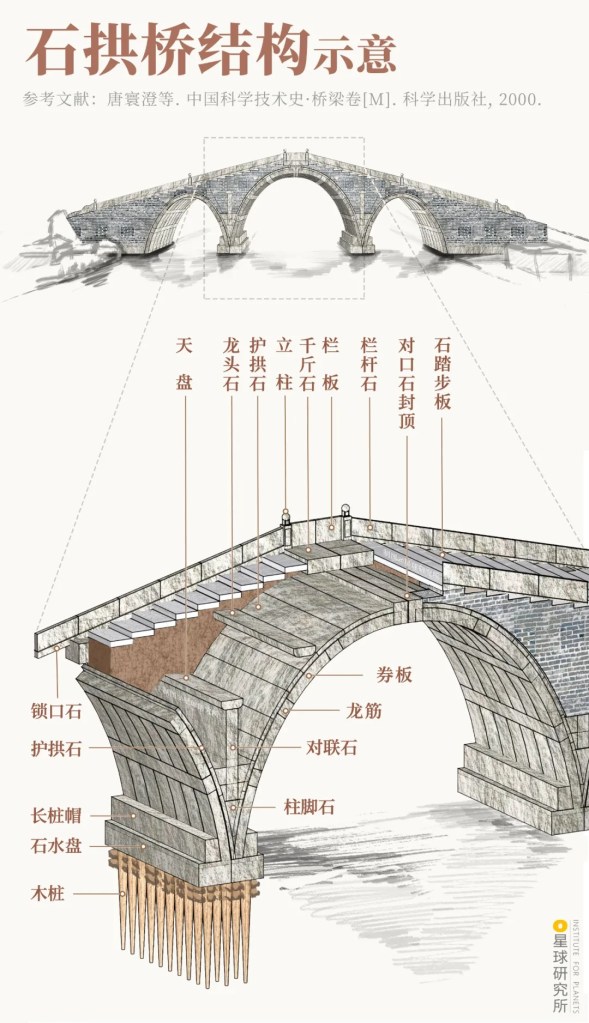

However, our ancestors gradually realised that straight and horizontal stone bridges struggled to stay strong over time, as the beams often started to fracture from the middle. They therefore replaced the stone beam with an arch to convert the vertical load into side thrust and avoid breakage of the beam. These are known as stone arch bridge (石拱桥).

(diagram: 陈随&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

Single-arch stone bridges are particularly common in the south. In the extremely elaborate canal system here, bridges are often interconnected or densely juxtaposed.

(photo: 卢文)

Due to the immense shipping demand, arch bridges in the south are always built with a tall arch. It is always a delight to punt through the mottled stone bridges and be lost in the emerald nature of these canal towns.

(photo: 林文强)

In contrast to the arch bridges in the south, those in the north are less tall and appear dull and weighty. The best example has to be the largest and grandest stone arch bridge set across the Inner Jinshui River within the Forbidden City in Beijing. If Inner Jinshui River were a full-drawn bow, the five parallel stone arch bridges crossing the river would be nocked arrows ready to strike. Plain and straight.

It was completed in Ming dynasty

(photo: 柳叶氘)

Although stone arch bridges appeared quite late, it immediately became a mainstream for bridge architecture and is still so among the currently existing ancient bridges. Thanks to the construction techniques inherited from stone beam bridges, the tool box for building a stone arch bridge was already quite comprehensive to begin with.

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

One can always add additional arches to the structure and make a multi-arch stone bridge (联拱石桥). A classic example of a double-arch stone bridge is the Taiping Bridge in Jiangxi, which has an extra arch on the bridge deck. The unique aesthetics of this bridge is further showcased by the layered roof tiles and ridges that curve upwards to the sky.

It was built in late Ming dynasty

(photo: 米兰的视界)

There are also triple-arch stone bridges, including the Ying’en Bridge in Wudang Mountain, Hubei, and Gongchen Bridge in Hangzhou.

(photo: 江南君)

Some bridges have five arches connected together, such as the Jimin Bridge in Ru’ning, He’nan, the water gate of Huangya Pass of the Great Wall in Ji County, Tianjin, as well as the Five-hole Bridge on the Black Dragon Pool in Lijiang, Yunnan, which sits in front of the Jade Dragon Snow Mountain.

(photo: 刘珠明)

Others have six arches, like the Zhusheng Bridge that leans on karst landforms unique to Guizhou.

It was completed in Ming dynasty

(photo: 李云鹏)

To go even further, the Lugou Bridge (also known as Marco Polo Bridge) has eleven arches, while the Seventeen-hole Bridge in the Summer Palace in Beijing and the Double Dragon Bridge in Jianshui, Yunnan, both have seventeen arches.

Completed during Qianlong’s rein in Qing dynasty, it is the largest stone bridge in the Summer Palace

(photo: 清心草)

And let us not forget the 53-arch Precious Belt Bridge in Suzhou.

Completed in Tang dynasty, the construction work was supervised by Wang Zhongshu, the then Suzhou governor; some say the bridge was named after Wang’s precious belt which he donated to make up for the construction cost, the other version of the story tells that bridge was named so because of its resembling appearance

(photo: VCG)

Stone arch structures can be further enhanced with additional arches on the shoulders of the main arch. We call these open-spandrel arch bridges (敞肩拱桥).

Open-spandrel arch technologies are still widely used today for reinforced concrete bridges

(photo: wzkdream)

The open spandrel design not only saves construction material and reduces self weight, it also facilitates flood discharge through the bridge body and stabilises the structure. Anji Bridge, the oldest open-spandrel arch bridge in the world completed back in Sui dynasty (581-618 AD), is still standing intact today having survived 10 major floods, 8 wars and numerous earthquakes. It is truly an everlasting wonder in the history of Chinese bridges.

(photo: 石耀臣)

3. The fusion of mechanics and aesthetics

From wood to stone, and further on to open-spandrel designs, Chinese bridge builders in the old times had been progressively striving for perfection in their applied mechanics and skills. Constructing a bridge had also transitioned from a mere engineering project into landscape creation.

Indeed, the best known lake views in China are never short of adorning bridges.

泠泠寒水带霜风,更在天桥夜景中

The icy stream burbles in the frosty wind,

杜牧《洛阳秋夕》

all dissolved in the scenery of the evening bridge.

Autumn evening in Luoyang by Du Mu

(photo: 张圣东)

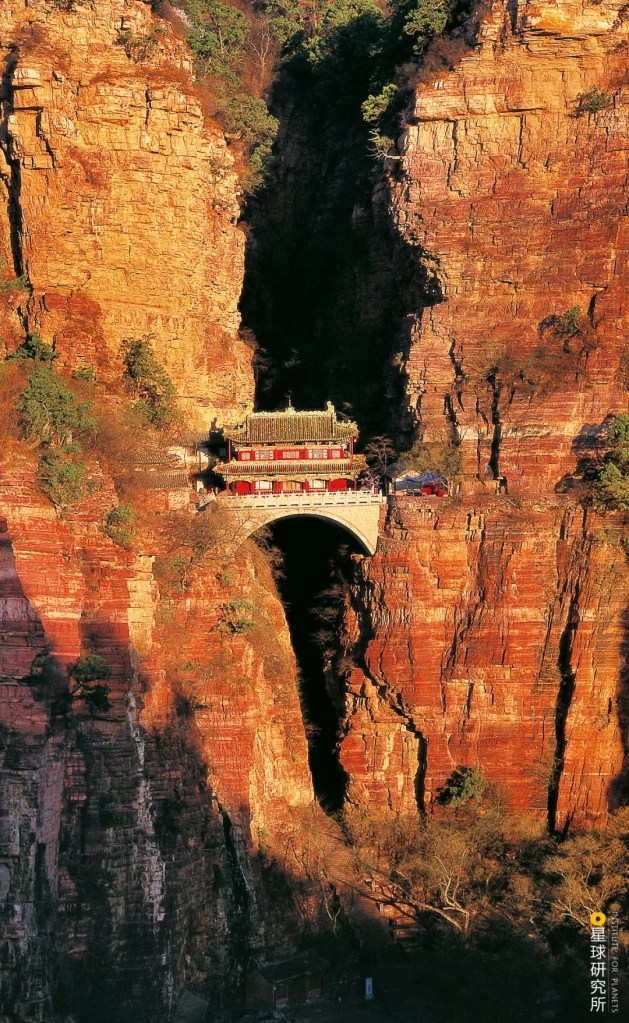

Even the most precipitous cliffs are accompanied by them.

千丈虹桥望入微,天光云影共楼飞

Atop the thousand-feet rainbow bridge every detail comes into view,

苍岩山石刻

alongside the clouds the tower soars in the daylight hue.

Stone inscription on Mount Cangyan

(photo: 吴卫平)

In the Jiangnan gardens, a strong and practical design was no longer the only pursuit of bridge builders. Instead, they sought to recreate the beauty of nature with stones.

虽由人作,宛如天开

A creation by hand, yet a gift from the heavens.

Yuantouzhu is famous private garden, where Wanlang Bridge is the key decoration of Lake Tai

(photo: 朱金华)

All these sceneries have left visitors with fond memories, and poets were more than generous with their words of compliment.

It was completed in Ming dynasty

(photo: 邓飞)

The poetic phrase “narrow bridge and quiet brooks” has even become the symbol of Jiangnan landscape. Even the Tang poet Bai Juyi was struggling to forget the mesmerising sight in his dreams.

扬州驿里梦苏州,梦到花桥水阁头

In the Yangzhou station I dreamt about Suzhou,

白居易《梦苏州水阁 寄冯侍御》

about her Flower Bridge and her waterside pavilion.

Waterside Pavilion of Suzhou in the Dream – to Official Feng by Bai Juyi

(photo: 朱露翔)

These sceneries were also depicted in classic landscape paintings, including the Pavilion of Prince Teng, A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Competition on the Jinming Pool, and many others. These paintings often come alive with the presence of an elegant ancient bridge.

This work of court painter Wang Ximeng in Northern Song dynasty is now kept in Forbidden City Museum

But bridges are more than just a scenery, they are a witness of change. They had seen the countless heartbroken poets bidding farewell with dearest friends, they had heard the many tears shed and the saddening departures spoken of. No wonder the indelible lines of the famous poem Maple Bridge at Night are cherished by many till this day.

History has also left its heavy marks on bridges. The Lugou Bridge (Marco Polo Bridge) reminds of the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War, whereas the Luding Bridge tells a thrilling story of the adventurous crossing by Red Army soldiers.

(photo: 李伟林)

When recalled from mythic tales and folklores, ancient bridges are ever more charming. There is the Magpie Bridge where the Cowherd and Weaver Girl meet once a year, the Fallen Bridge where Xu Xian and Madame White Snake finally let go of each other, and the Bridge of Helplessness where the deceased are guided forth. There is also Weisheng the infatuated who was waiting to meet his lover on a bridge but eventually drowned in a flood just to keep his promise.

水来,我在水中等你;火来,我在灰烬中等你

When water comes, I will be there for you in the water;

洛夫《爱的辩证》

when fire comes, I will be there for you in the ashes.

Dialectic on Love by Luo Fu

(photo: 清溪)

Wipe away the vicissitudes one will sense deep affection in ancient bridges. This feeling sometimes pours out with great momentum…

长桥卧波,未云何龙?

杜牧《阿房宫赋》

复道行空,不霁何虹?

How can there be a hovering dragon in a cloudless sky? It is but a crouching bridge atop the tide.

How can there be an arching rainbow on a rainless day? It is but a dangling corridor between pavilions.

Rhapsody on the Efang Palace by Du Mu

(photo: 堂少)

…other times it seeps out as troubled weeps.

细水涓涓似泪流,日西惆怅小桥头

A tiny brook flows by like a stream of tears,

白居易《小桥柳》

the setting sun sighing over the end of bridge.

Willow by the Small Bridge by Bai Juyi

(photo: 方托马斯)

It may be a grieve recollection…

伤心桥下春波绿,曾是惊鸿照影来

The green ripples below the mournful bridge

陆游《沈园二首·其一》

wavers a reflection of the beauty that once was.

Two Sets on Shen Garden: Set One by Lu You

(photo: 赵永清)

…or a joyful outing.

水底远山云似雪,桥边平岸草如烟

Distant mountains in the water are surrounded by snowy clouds,

刘禹锡《和牛相公游南庄醉后寓言戏赠乐天兼见示》

flat banks by the bridge are blanketed with foggy grass.

An optimistic fable and revelation while drunk during a trip to Nanzhuang with Niuxianggong by Liu Yuxi

(photo: 文林)

It stages the reluctant partings…

从来只有情难尽,何事名为情尽桥

There have only been friendships that never end,

雍陶《题情尽桥》

why should the bridge be named “friendship ends”.

On the Bridge of Ending Friendship by Yong Tao

(photo: 吴卫平)

…as well as the resolute journeys.

水从碧玉环中去,人在苍龙背上行

Water flows past through the jasper rings,

出自刘百熙的对联

men move forward on the dragon’s back.

A couplet by Liu Baixi

(photo: VCG)

It returns every spring…

春来无处不春风,偏在湖桥柳色中

Warm breeze brushes all in spring,

陆游《柳》

yet it stays with the willow by the bridges on lake.

Willow by Lu You

(photo: 伍敏君)

…while lingering in the past.

二十四桥明月夜,玉人何处教吹箫

As the moon shines on the Twenty-fourth Bridge,

杜牧《寄扬州韩绰判官》

where are you to teach the ladies play flute?

To Yangzhou Magistrate Han Chuo by Du Mu

(photo: 非渔)

Chinese ancient bridges — an accomplishment in engineering and the pursuit of landscaping ideals, a witness of change and a totem for affection, and on top of all, the flawless fusion of mechanics and aesthetics.

Production Team

Text: 李张子薇

Photos: 余宽、谢禹涵

Design: 王申雯

Maps: 陈志浩

Review: 撸书猫、张靖

Cover photo: 清心草

Expert review (in alphabetical order)

Prof Chen Baochun – School of Civil Engineering, Fuzhou University

Prof Li Yadong – School of Civil Engineering, Southwest Jiaotong University

Mu Xiangchun (Professor-grade senior engineer) – Beijing Municipal Engineering Design and Research Institute Co., Ltd.

Special thanks

China Communications Publishing & Media Management Co., Ltd.

References

[1]唐寰澄等. 中国科学技术史·桥梁卷[M]. 科学出版社, 2000.

[2]王俊. 中国古代桥梁[M]. 中国商业出版社, 2015.

[3]茅以升等. 中国古桥技术史[M]. 北京出版社, 1986.

[4]肖东发等. 古桥天姿——千姿百态的古桥艺术[M]. 中国出版社, 2015.

[5]中国公路学会. 中国廊桥[M]. 人民交通出版社股份有限公司, 2019.

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光