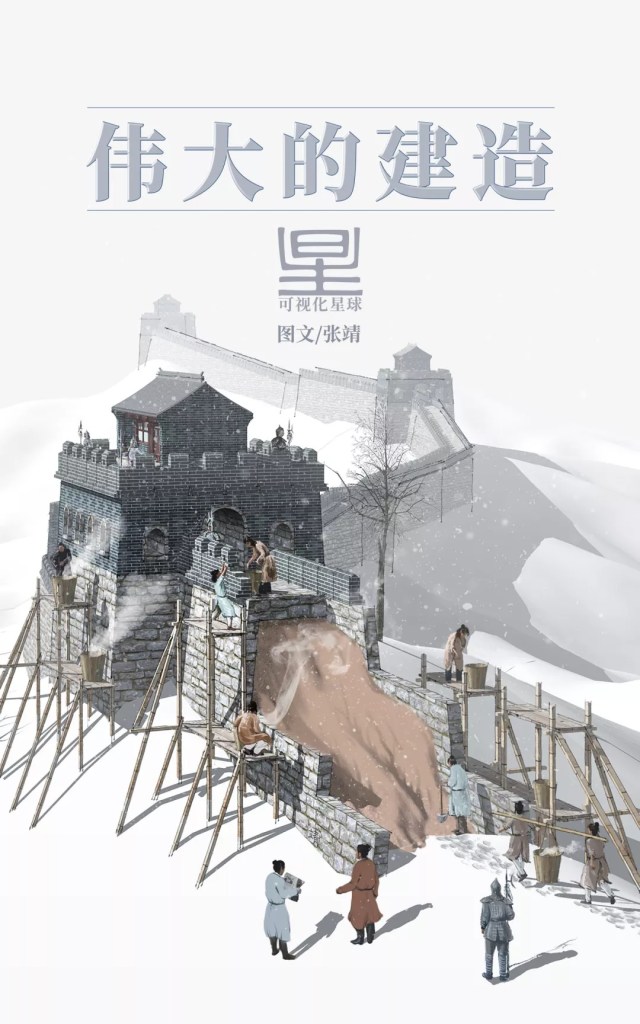

Original piece: 《长城是如何建成的?》

Produced by 可视化星球 @ Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 张靖

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

In the northern parts of China, there stands a towering wall that stretches 21,196,180 metres1 across from head to tail.

This giant dips the sea in the far east…

(photo: 任世明)

and cuts through deserts in the deep west.

(photo: 吴玮)

It climbs mountains…

(photo: 周青阳)

…and strides past the plains.

Geographically, this bolson plain is located at where the Loess Plateau and Mongolian Plateau meet

(photo: 张伟)

It squeezes through fertile farmlands and lush waters…

(photo: 刘忠文)

…and embraces villages and towns.

(photo: 吴祥鸿)

There is just no way to capture its whole structure by eyes. For centuries, the Chinese have called it the Ten-thousand-mile Rampart (万里长城). And to many Westerners, the enchanting existence of this wall cannot be attributed simply to its size, that they have decided to give it another name:

THE GREAT WALL OF CHINA

(photo: VCG)

Crowned with such a supreme honour, the Great Wall obviously has far more to offer than its mere size. But how did it manage to live up to its name for the past thousands of years until today? Before answering this question, it is perhaps a good idea to first get a glimpse of how it was built.

1. The magnificent emergence

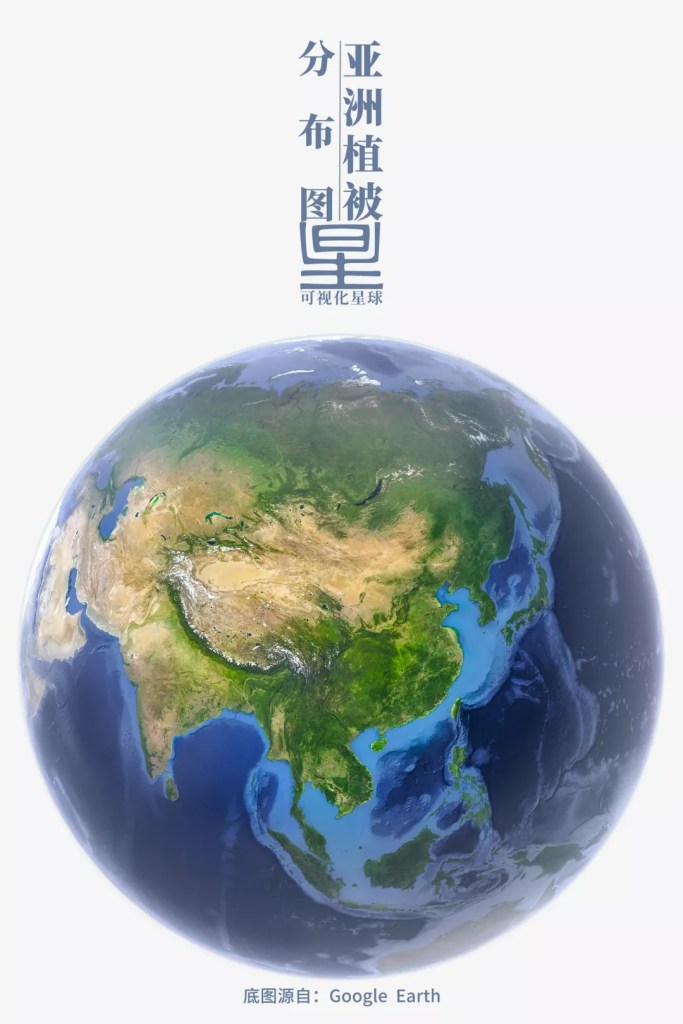

Looking at the map of East Asia, one will realise that this vast land can be divided into two parts painted with strikingly different colours. The part in green has a high vegetation coverage, whereas the other in yellow is relatively naked.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

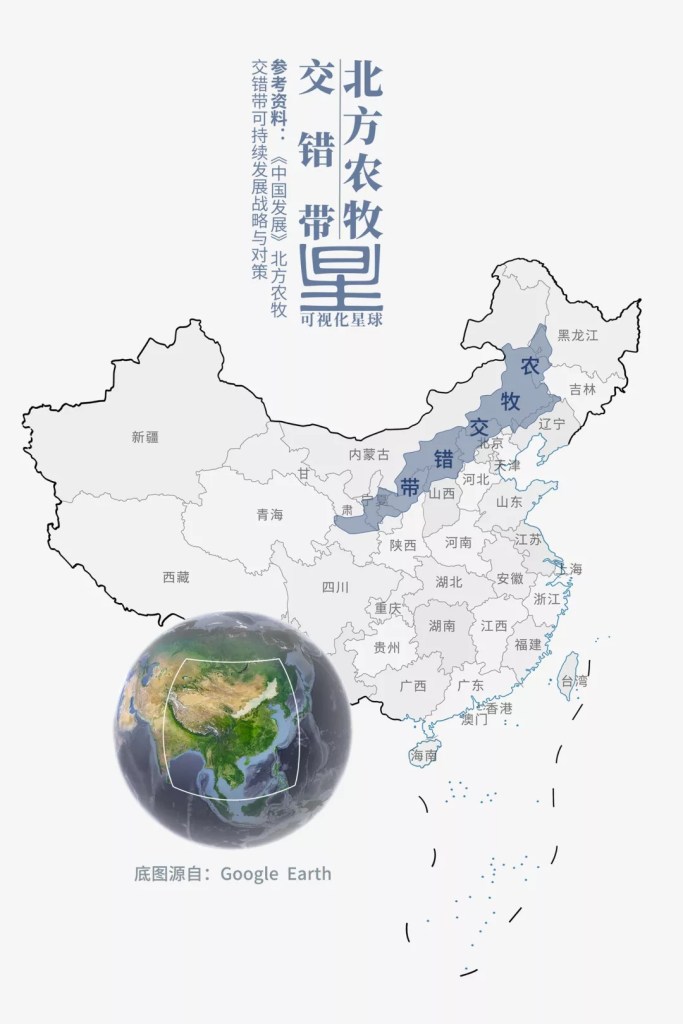

This makes a huge difference for those who live there. The land covered in green is fertile and suitable for farming, which catalysed early development of agriculture. In contrast, the areas in yellow are mostly barren land, so people living there could only engage in animal husbandry and become nomads. The intersection of these two regions forms a natural border known as the agro-pastoral zone.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

As far back as during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (~771-221 BC), the concept of private ownership of land was already prevalent in farming areas to the south of the agro-pastoral zone. Feudal states were constantly waging wars to either acquire more land or protect theirs from other states. To get the upper hand, they all invested heavily on the development of a comprehensive defence system. This was when the Great Wall started to make its first appearance.

States: Qin (秦), Chu (楚), Qi (齐), Yan (燕), Zhao (赵), Zhongshan (中山), Han (韩), Wei (魏) Song (宋), Lu (鲁), Yi (夷)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

At that time, life on one side of the agro-pastoral zone was vastly different from that on the other side. Agricultural societies in the south saw enormous growth in productivity, while nomadic people in the north led a homeless life. Whenever natural disasters hit, nomads would rush to the south and fight the locals for resources. These endless conflicts grew rapidly in scale, and eventually prompted the construction of blockade walls that meander tens of thousands of miles.

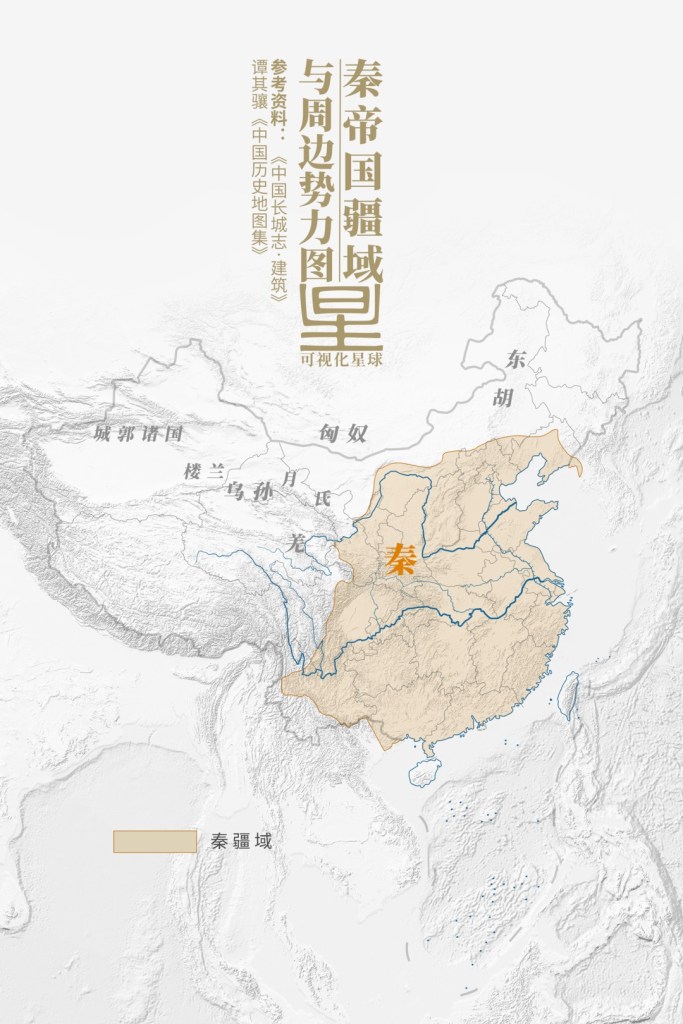

2. The rise of a great empire

In 221 BC, Qin Shi Huang (lit. ‘first emperor of Qin’) conquered the six other warring states and unified all of China. The unification greatly accelerated accumulation of wealth within the border, and Qin was in urgent need for an effective defence measure to protect everything the empire possessed.

Other states from right to left: Donghu (东胡), Xiongnu (匈奴), Yuezhi (月氏), Qiang (羌), Wusun (乌孙), Loulan (楼兰), other citadel states (成郭诸国)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

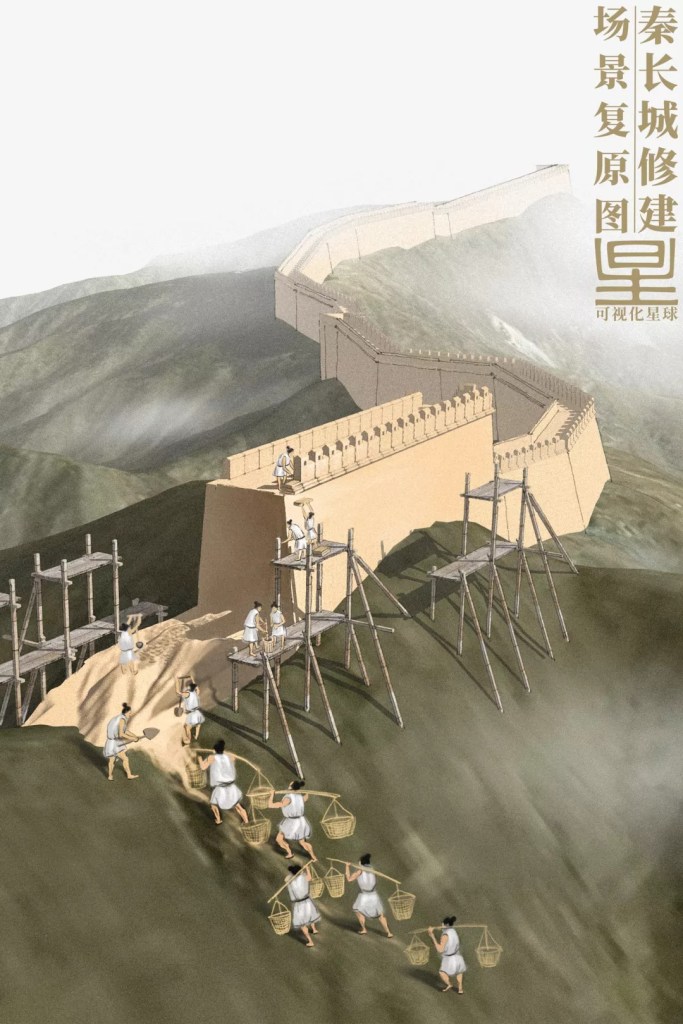

To solve this issue, Qin emperor ordered General Meng Tian to gather 300,000 soldiers and restore and expand the Great Wall sections previous built by Yan, Zhao and Qin. This was the first large-scale construction of the Great Wall ever in Chinese history.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

It took more than a decade for the builders to finish the task. Thereafter, the Qin Great Wall essentially guarded the entire northern frontier of the empire, from Min County (Lintao) in Gansu in the west all the way to Korean Peninsula (Liaodong) by the eastern coast. Since the total length of the wall literally exceeded 10,000 miles, it was given the name Ten-thousand-mile Rampart.

Min County/Lintao (岷县/临洮), Liaodong (辽东)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

Later in Han dynasty, the ambitious Emperor Wu began to set his eyes on the Western territories. After Huo Qubing, General of Agile Calvary then, conquered the Xiongnu people of Hexi, two passes and four prefectures (两关四郡) were built in the region.

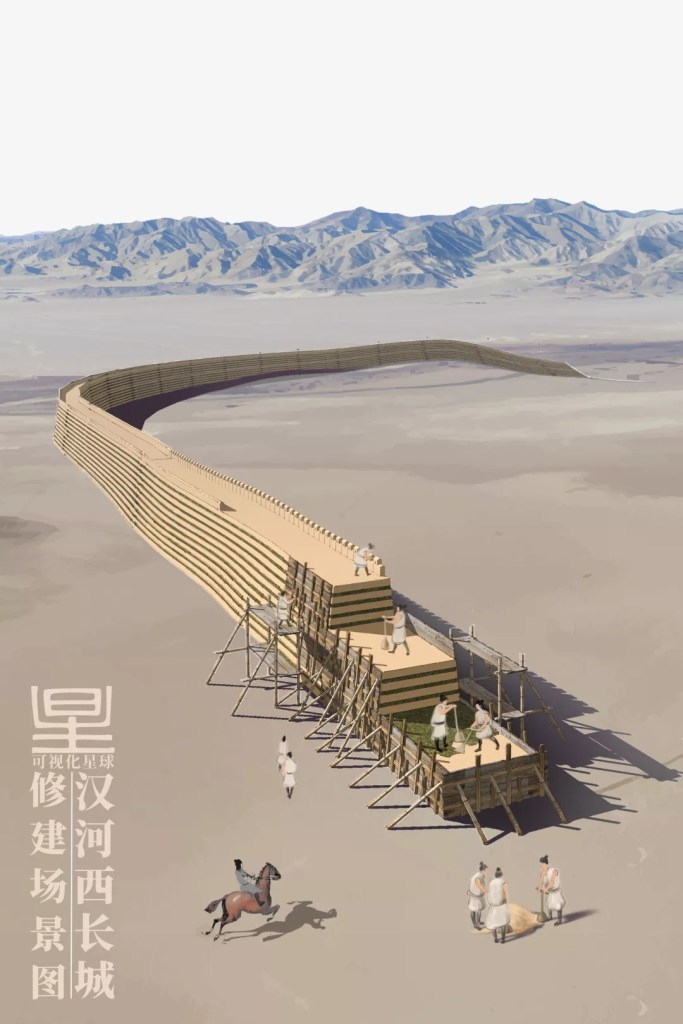

To prevent further incursions of the Xiongnu from the north, Emperor Wu of Han started building the Great Wall again in large scale. The Han Great Wall was constructed with the same technologies used in the Qin dynasty, which was to insert layers of vegetation within the rammed earth for compaction of the wall body. Simple and efficient.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

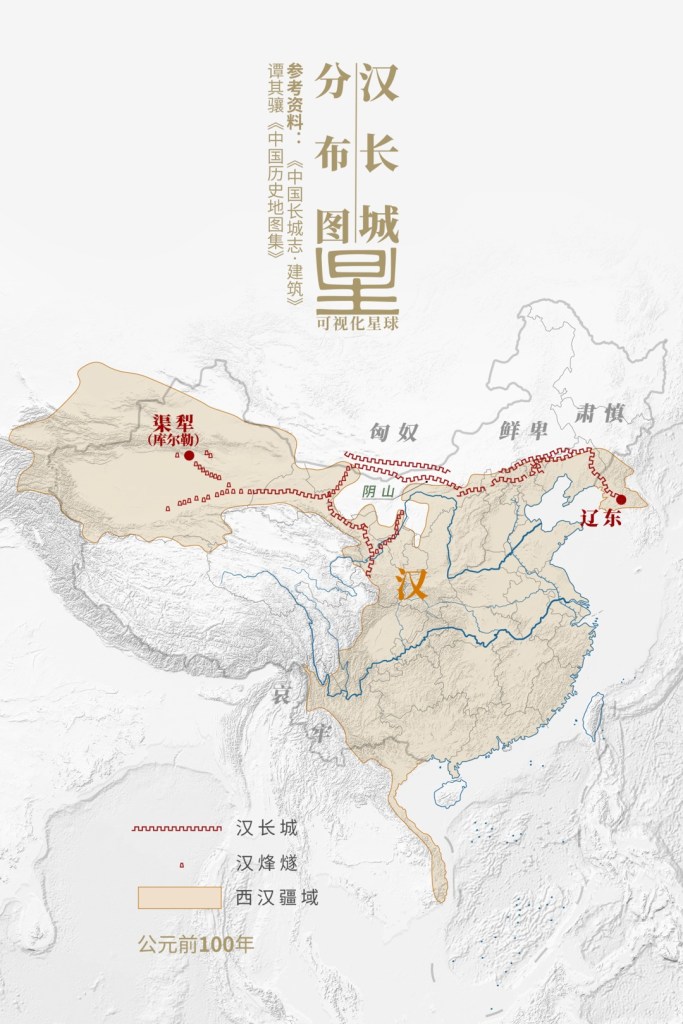

Years later, the completed Han Great Wall lined the entire northern border of Han, running between Quli (today’s Korla) in the west and Liaodong in the east. To defend against the valiant Xiongnu, two more parallel walls were built north of Yin Mountains in the Han dynasty.

Locations: Quli/Korla (渠犁库尔勒), Liaodong (辽东), Yin Mountains (阴山), Xiongnu (匈奴), Xianbei (鲜卑), Sushen (肃慎)

Symbols: Han Great Wall (汉长城), Han beacons (汉烽燧), Western Han territory (西汉疆域)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

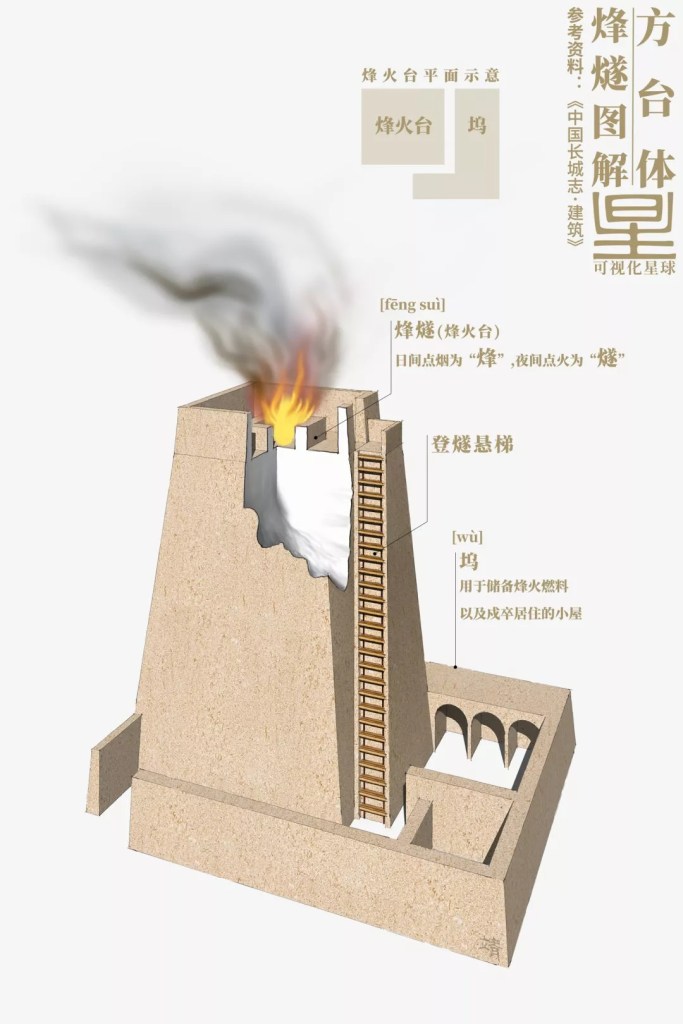

Owing to the enormous span of the Han Great Wall and the low population density in Hexi regions, much of the wall was stationed only with tiantian (天田, lit. heaven fields, patches of land covered with a layer of fine sand used to track footprints of potential offenders) and fengsui (烽燧, lit. beacon; also known as fenghuotai, 烽火台).

Fengsui (烽燧): smog produced in the daytime is known as ‘feng’, while firelight lid at night is ‘sui’

Suspended ladder (登燧悬梯), Wu (坞, lit. dock, used as storage for beacon fuel and a barrack)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

Being the transmission tool for alarm signals, each fengsui had to be placed at a reasonable distance apart. As a rule of thumb, there should be a small station every 5 miles and a major station every 10 miles, so that when a war breaks out, the arrays of fengsui would be able to communicate important war intelligence to each military base quicker than on a horseback.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

The prospering Silk Road that emerged later was the best proof of the effectiveness of Han Great Wall in the Hexi regions.

Blue dotted line: Silk Road (丝绸之路)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

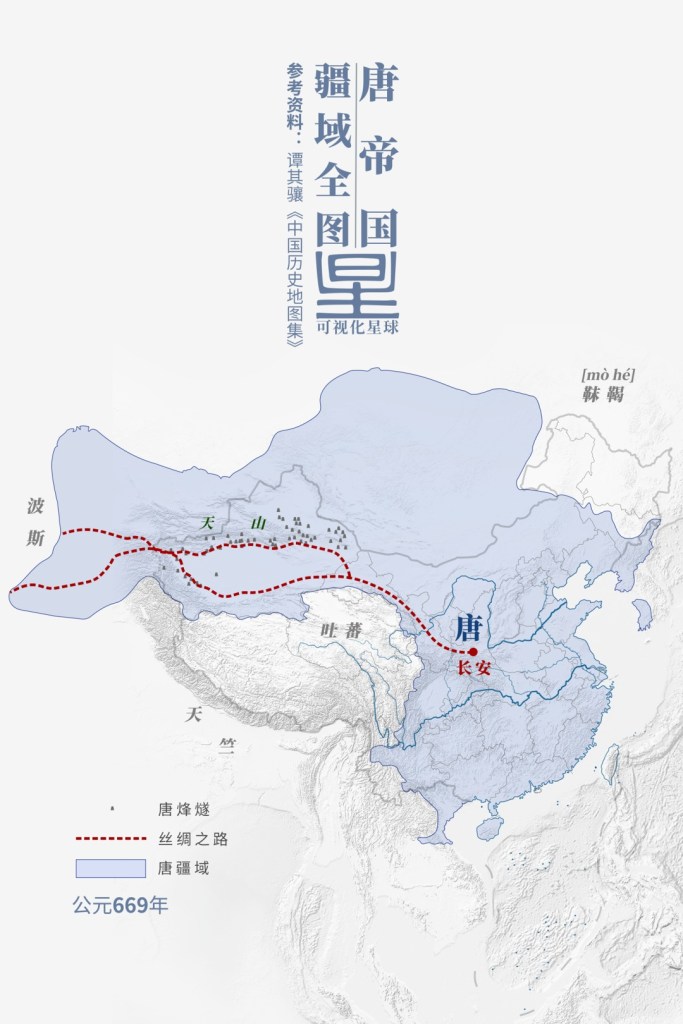

During the Tang dynasty, in order to ensure travellers’ safety along the Silk Road, the government built large numbers of fengsui around Tianshan Mountains. In other frontier regions, on the contrary, fanzhen (藩镇, lit. buffer towns) were used for security control, which had allowed further expansion of Tang’s territory. However, this seemingly wise border defence policy was directly responsible for the breakaway of and land occupation by fanzhens in late Tang dynasty, which eventually opened the chaotic era of Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms.

Red dotted line: Silk Road (丝绸之路); Blue: Tang territory (唐疆域)

Chang’an (长安), Turpan (吐蕃), Persia (波斯), Tianzhu (天竺), Tianshan Mountains (天山)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

From then on, construction and maintenance of the Great Wall had become an indispensable part of national defence measures in all succeeding Chinese dynasties. Even some of the ethnic minorities from the north who managed to overcome the Great Wall and seize the throne on the Central Plains decided to make good use of this wall against other nomadic tribes further north. The Jin dynasty founded by the Jurchen people extended the Great Wall deep into the heart of the northern grassland.

Unlike the Great Wall sections on the Central Plains, Jin Great Wall was mostly trenches and earth walls

Symbols: Jin Great Wall (金长城), Jin territory (金疆域)

Locations: Hulunbuir Grassland (呼伦贝尔草原), Korchin Grassland (科尔沁草原), Xilingol Grassland (锡林郭勒草原)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

Contrary to previous dynasties, the Great Wall built in Jin dynasty had watchtowers rising from the wall body, as well as many similar standalone structures on the interior side. These structures offered the Great Wall an extra dimension of protection and strengthened the ability of defence in depth.

The structures protruding from the wall body were watchtowers

(photo: 方忠诚)

The scale of Jin Great Wall was much smaller than that of Qin or Han, but all these exploratory defence technologies provided valuable experience later for the construction of Ming Great Wall, another record-breaking mega project.

3. The majestic upgrade

After ruling China for almost a hundred years, the rulers of Yuan dynasty were driven out in 1368 AD and pushed north of the Great Wall by forces of Ming dynasty. To keep the Mongolians out for good, the Ming empire continued to upgrade the Great Wall throughout the entire dynasty.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

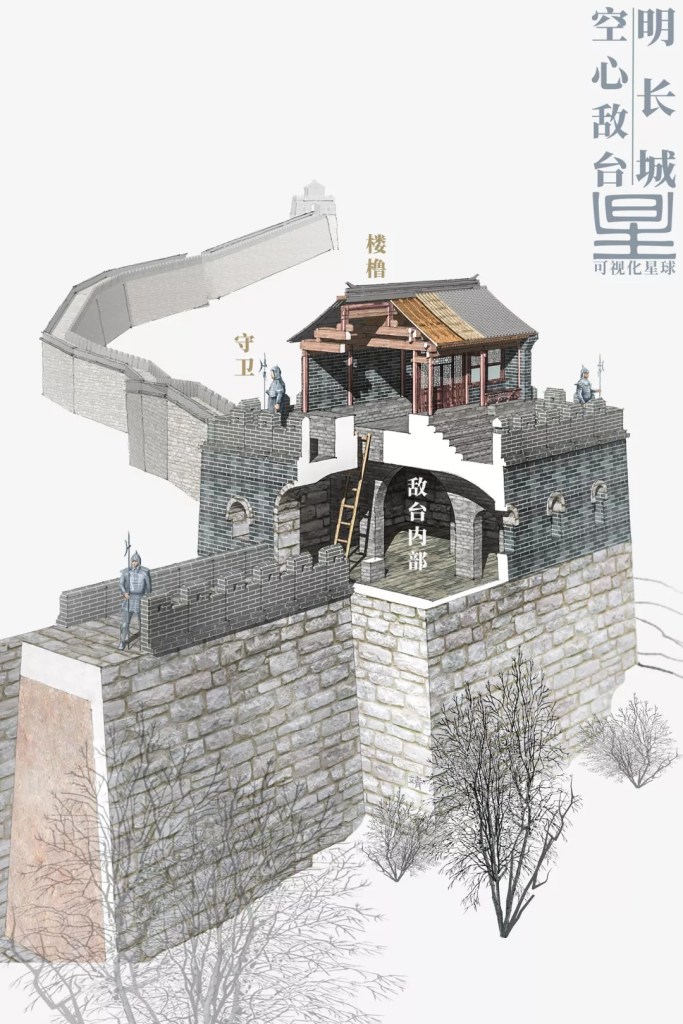

During the Ming dynasty, there were three occasions of extensive refurbishment and expansion of the Great Wall using techniques inherited from previous dynasties, with the last occasion being the largest in scale. Construction teams led by Tan Lun and Qi Jiguang successively improved the defence capabilities of the Great Wall. In particular, the hollow watchtowers constructed during Qi Jiguang’s time became the most representative icon of the Ming Great Wall.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

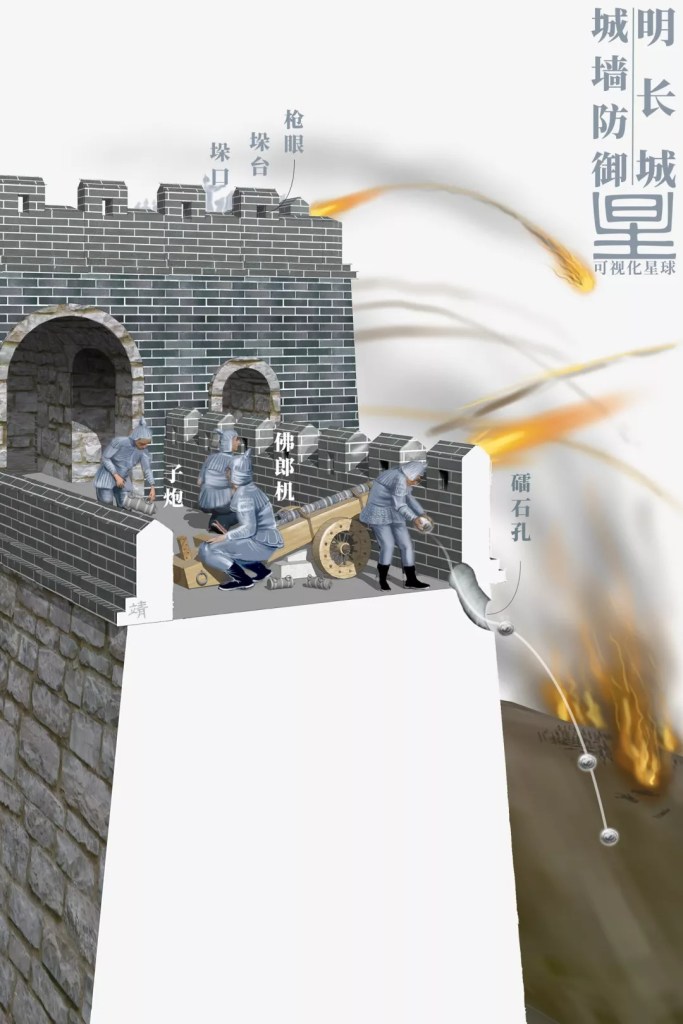

Starting in Ming dynasty, rocks and bricks were used to face the Great Wall, making its structure even stronger and more durable. In addition, there were combat devices installed, including gun holes, crenellations, stacking platforms and stone missile channels.

Gun hole (抢眼), crenellation (垛口), stacking platform (垛台), stone missile channel (礌石孔), breech-loading swivel gun (佛郎机), breech block (子炮)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

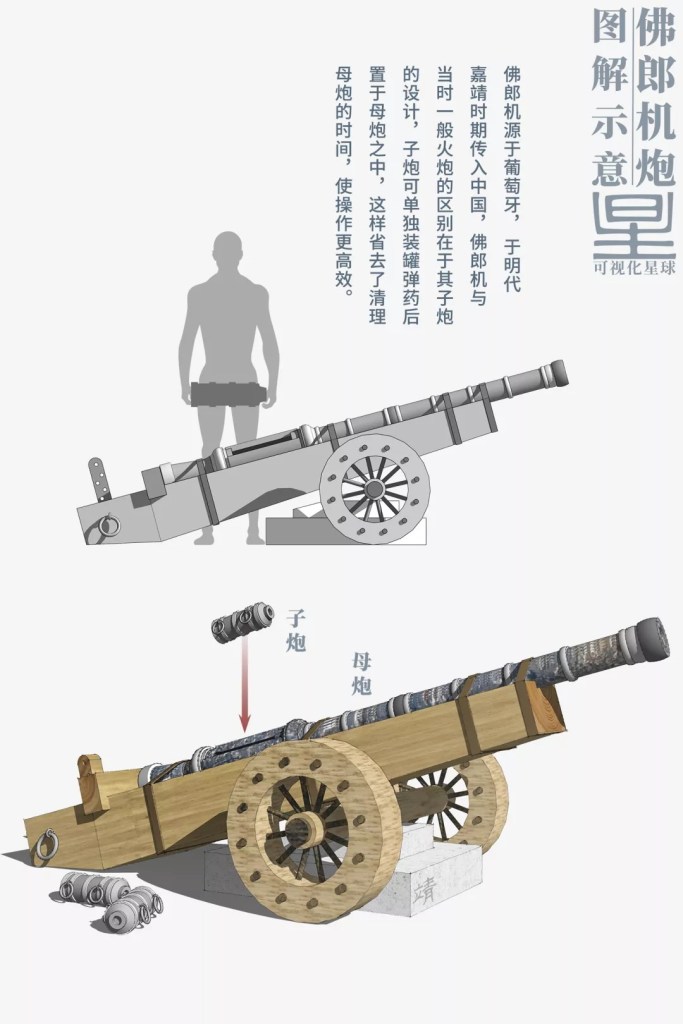

In order to further strengthen the defence capability, the Ming Great Wall was armed with breech-loading swivel guns (also known as Frankish guns in China), a powerful artillery first developed by the Portuguese.

Breech-loading swivel guns, or Frankish guns in Chinese, originated in Portugal and was adopted in China during Jiajing period of Ming dynasty. What distinguished the Frankish guns from contemporary cannons was the design of the breech block, which could be prepared for gunpowder filling in advance before insertion into the cannon. Without the need to clean the cannon after every firing, it was much more efficient and had a higher firing rate.

Structure: breech block (子炮), breech-loading cannon (母炮)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

There were also numerous passes erected at the intersections of the Great Wall and major traffic arteries.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

During wartime, passes became the military strongholds at the frontier and served as access control points for any personnel movement; whereas in times of peace, they facilitated trade and communication at the borders.

(photo: 杨东)

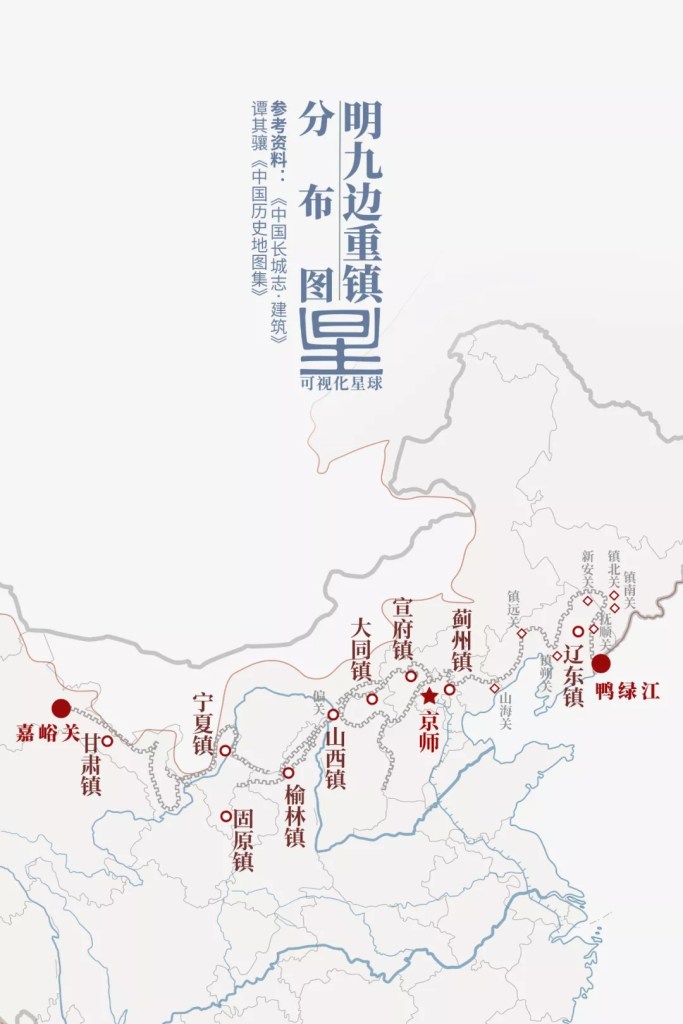

In addition to these passes, a string of military settlements were established along the Great Wall, known as the Nine Garrisons of the Ming Dynasty.

Left to right: Garrison of Gansu (甘肃镇), Garrison of Ningxia (宁夏镇), Garrison of Guyuan (固原镇), Garrison of Yulin (榆林镇), Garrison of Shanxi (山西镇), Garrison of Datong (大同镇), Garrison of Xuanfu (宣府镇), Garrison of Jizhou (蓟州镇), Garrison of Liaodong (辽东镇)

Other major locations: Jiayu Pass (嘉峪关), capital city (京师), Yalu River (鸭绿江)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

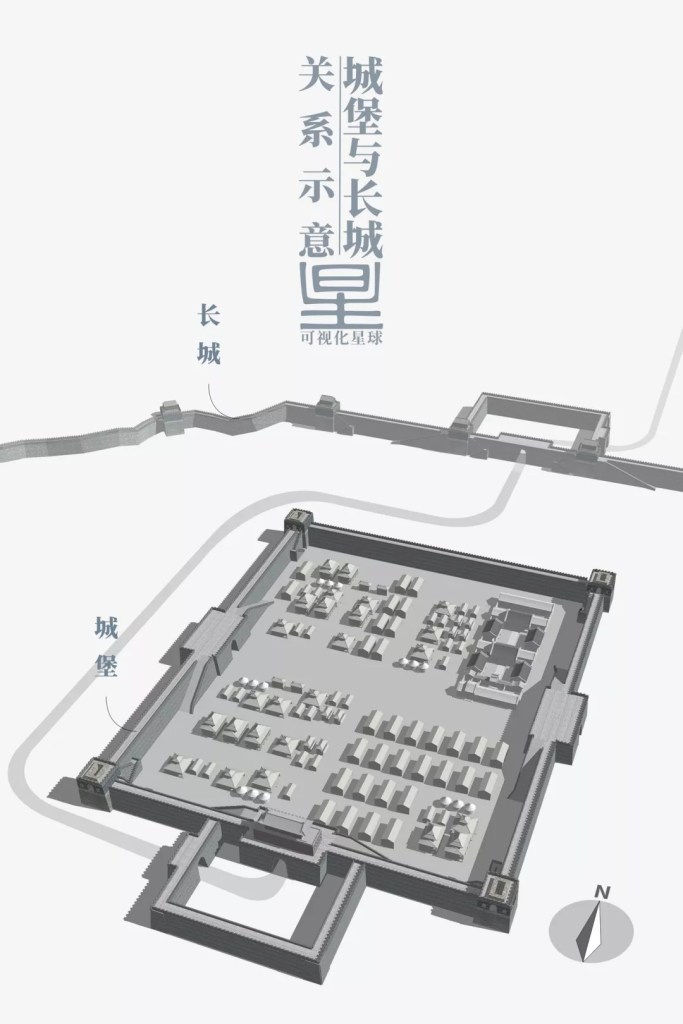

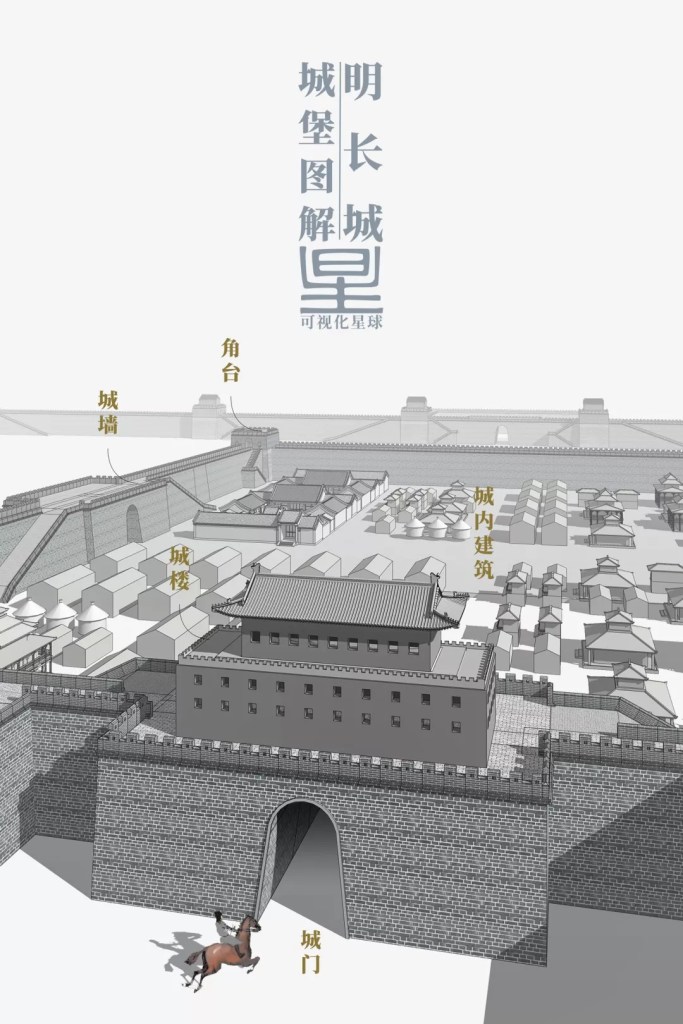

Housing mainly the border soldiers and their families, these garrisons were a major component of the defence system known as Great Wall castles.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

Having castles along the Great Wall meant that the frontier was always stationed by a standing army, largely avoiding the significant cost for dispatching troops from the Central Plains during a war. Therefore, castles had to be better militarised and prepared for approaching enemies than a watchtower.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

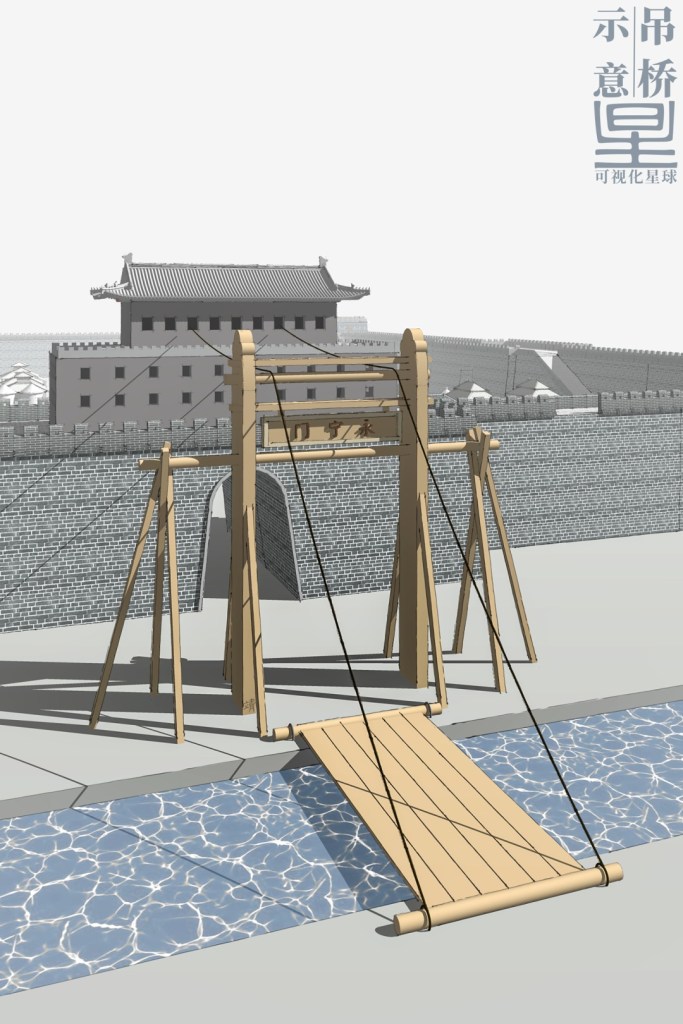

Castles with greater military significance were usually surrounded by a moat, which was crossed by a drawbridge.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

This drawbridge would be raised up during a war to stop the advancing enemies.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

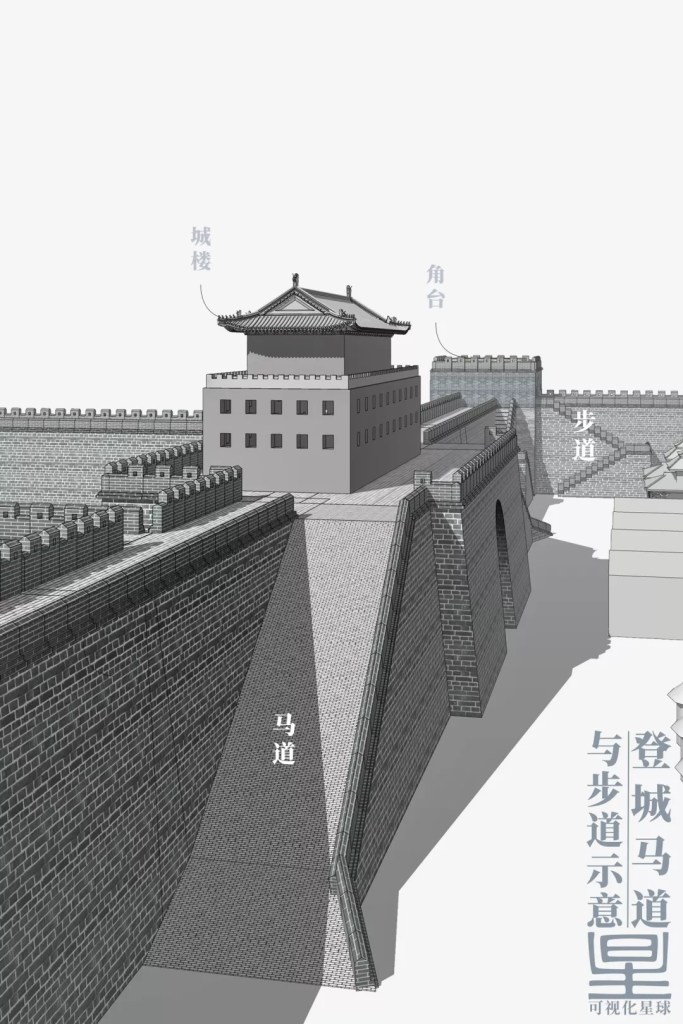

And inside the castle, there were horse trails and stairs for rapid combatant deployment onto the castle wall. For larger walls, chariots could directly go up on the wide horse trails.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

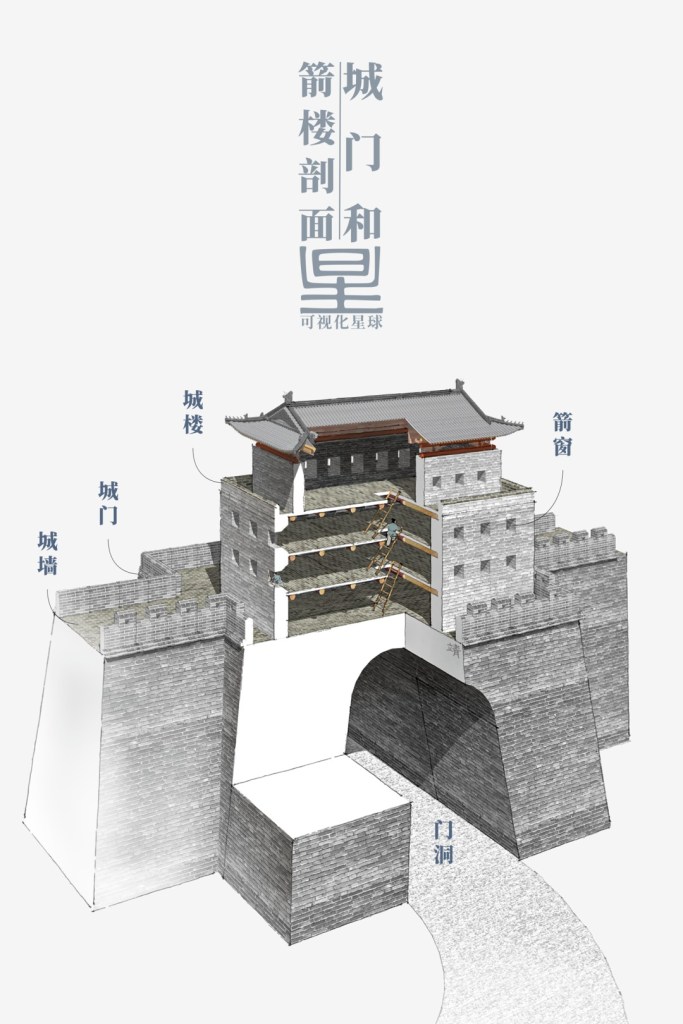

On each side of the castle, defensive wall was always guarded by an enormous gate stacked upon by a gate tower or archery tower, from which arrows could rain down on charging enemies.

Gate tower (城楼), archer window (箭窗), gate (城门), gateway (门洞)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

Major gates were often held by an additional outer gate, where the space between the two gates was called a barbican, or ‘urn city‘. If the enemy broke into the first gate, they would be surrounded within the barbican like a turtle in the urn waiting to be annihilated.

There would be two to three layers of barbicans configured at the most important gateways

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

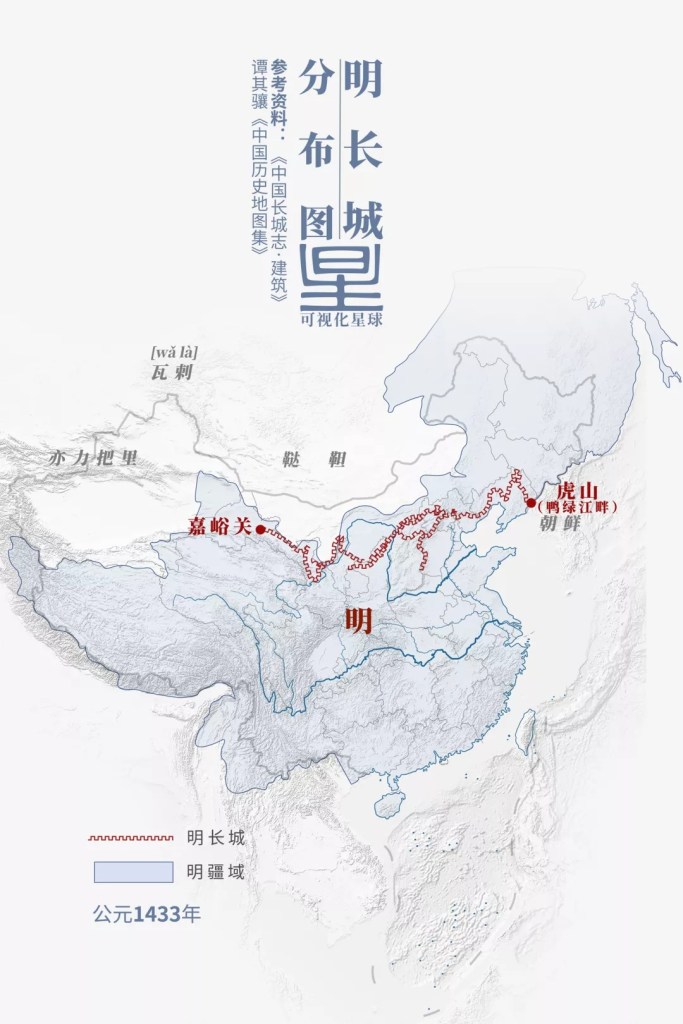

Construction work for the Ming Great Wall almost never stopped throughout the 270 years the dynasty lasted, as there were more than 20 recorded occasions of large-scale constructions. If all the natural barriers along the way were included, the Ming Great Wall would be travelling over 8800 kilometres in total.

Symbols: Ming Great Wall (明长城), Ming territory (明疆域)

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

As such, a comprehensive defence system composed of border walls, beacons, watchtowers, passes and castles had turned the empire’s entire frontier into single interconnected structure.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

It meanders through the towering mountain ranges in northern China like a colossal dragon.

(photo: 杨东)

The construction time and scale of Ming Great Wall was unmatched by any other Great Walls ever built. It has the most exquisite appearance, the strongest structure, and the most diverse and comprehensive defence system. It is truly the classic of all Great Walls.

4. The grand tale

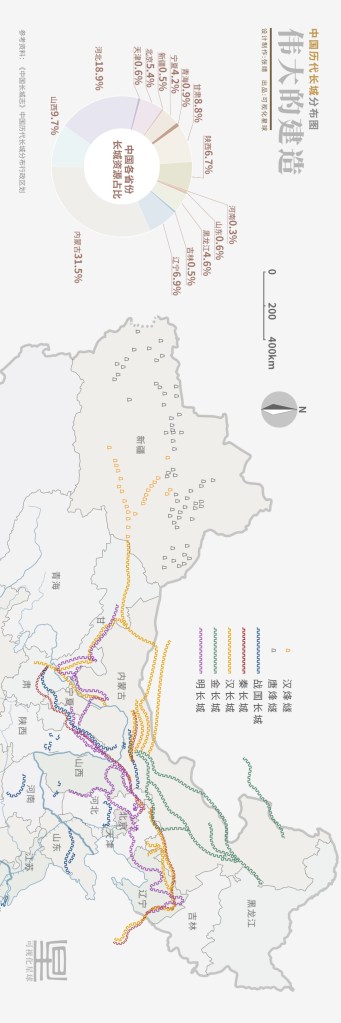

From its birth during the Warring States period to the fall of Ming dynasty more than 2000 years later, the Great Wall had grown beyond 20,000 kilometres and penetrated 15 provinces in today’s China.

Proportion of Great Wall in each province/municipality (pie chart): Inner Mongolia (31.5%), Hebei (18.9%), Shanxi (9.7%), Gansu (8.8%), Liaoning (6.9%), Shaanxi (6.7%), Beijing (5.4%), Heilongjiang (4.6%), Ningxia (4.2%), Qinghai (0.9%), Tianjin & Shandong (0.6%), Xinjiang & Jilin (0.5%), Henan (0.3%)

Map: blue, Warring States; red, Qin; yellow, Han; green, Jin; purple, Ming

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

It created the Great Wall Zone2 in northern China, a vast stretch of land which had a long-lasting impact on the productivity and lifestyle in surrounding regions.

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

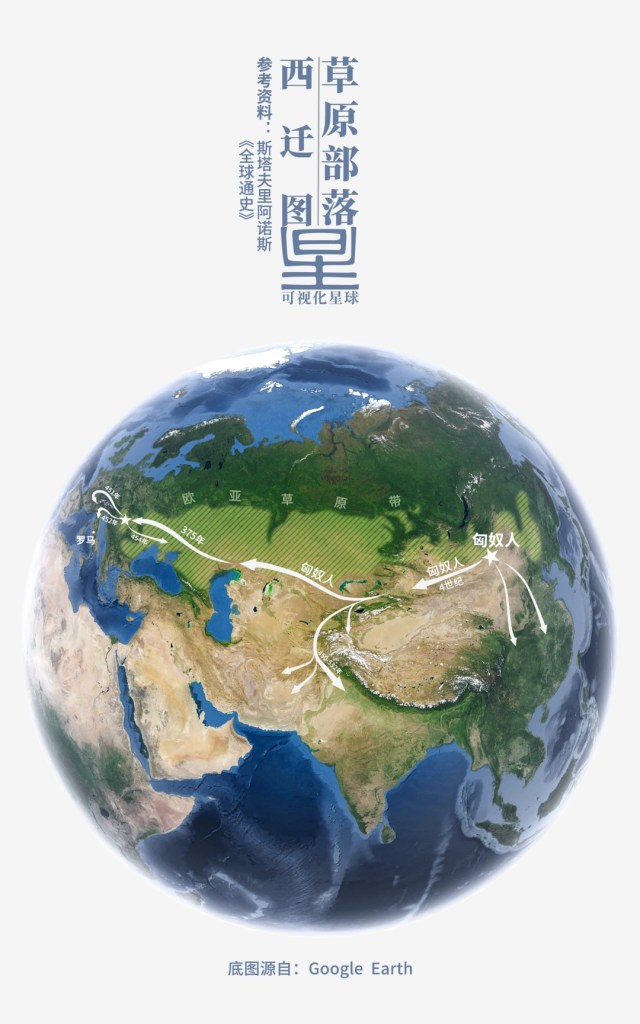

On one hand, the Great Wall protected farmlands of the local people, and on the other, facilitated the formation of alliance and growth of nomadic tribes. The latter in turn deeply influenced the contemporary political landscape of Eurasia continent.

As historian L.S. Stavrianos had put it in his book:

A defeat before the Great Wall of China or a stumbling block such as the formation of an aggressive tribal confederacy in Mongolia, frequently turned the nomads westward. A series of invasions, like a train of shocks moving ever further west, ended finally in nomadic incursions across the Oxus or Danube or Rhine rivers.

The World to 1500: a Global History by Leften Stavros Stavrianos

(diagram: 张靖, 可视化星球)

Whereas within China, the cruel oppression on the ordinary civilians owing to the labour-intensive construction has made the Great Wall a synonym for horrible suffering. To ease people of this devastating memory, the Ten-thousand-mile Rampart was euphemistically renamed the Frontier Wall by the Ming government.

Nevertheless, the Great Wall has had more than just a few positive impacts on the thriving communities at the borders. In peaceful eras, it substantially facilitated economic exchange in border zones and promoted movement and development of population along its stretch.

Today, some sections of the Great Wall may have been engulfed by nature…

(photo: 周青阳)

…or reduced to ruins.

(photo: 刘忠文)

Others sections have become a farmyard…

(photo: 王牧)

…or are slowly being forgotten.

(photo: 王牧)

(photo: 陈爱红)

Currently, there are still up to a hundred million people3 living in the Great Wall Zone. Their production and lifestyle will inevitably affect the preservation of the Great Wall, which is already facing challenges posed by natural weathering.

(photo: 王牧)

The time for the Great Wall being a military defence system is long gone, and much of the wall is not even at the frontier and have become inner walls. However, the Great Wall culture continues to influence all those who revolve around it.

Throughout the centuries, so many tragic tales were told right here, but all had faded away in the wind. Along the Great Wall they converge, weaved together into a stream of sorrow, sometimes tempestuous, sometimes tame.

… The End …

Production Team

Text: 张靖

Diagrams: 张靖

Photos: 谢禹涵、蒋哲睿

Review: 风子、撸书猫、陈思琦

Expert review

Tianjin University — Prof Zhang Yukun & Assoc Prof Li Zhe

Chinese Academy of Cultural Heritage — Zhang Yimeng

Beijing Institute of Cultural Heritage — Shang Hang

Footnotes

1. The Great Wall sections constructed in different dynasties are distributed across a relatively vast area and not a single intact wall. This figure is estimated based on the existing Great Wall structure and not the total length of all sections ever built.

2. This term was first coined by Owen Lattimore, an American sinologist, in his book Inner Asian Frontiers of China. He proposed that the Great Wall is not an absolute ‘line’ that marks the border, but a vast fringe territory substantiated by historical events. The concept of “Great Wall Zone” has been widely accepted by Chinese academics, and was adopted in Chronicles of the Great Wall of China written by the Great Wall Society of China.

3. According to the Regulation on the Protection of Great Wall released by the National Cultural Heritage Administration, existing sections of the Great Wall is currently distributed in 404 counties across 15 provinces, which together are home to more than 100 million people.

References

1:景爱|《中国长城史》,[M]上海人民出版社,2006年

2:汤羽扬|《中国长城志·建筑》,[M]江苏凤凰科学技术出版社,2016年

3:张玉坤|《中国长城志·边镇·堡寨·关隘》,[M]江苏凤凰科学技术出版社,2016年

4:董耀会、贾辉铭|《中国长城志·总述·大事记》,[M]江苏凤凰科学技术出版社,2016

5:李鸿宾、马保春|《中国长城志·环境·经济·民族》,[M]江苏凤凰科学技术出版社,2016年

6:张柏、黄景略、朱启新等|《中国长城志·遗址遗存》,[M]江苏凤凰科学技术出版社,2016年

7:孙志升|《中国长城》,[M]中国文史出版社,2005年

8:国家文物局|《长城保护总体规划》,[S]国家文物局,2019-2035年

9:肖鲁湘、张增祥|《农牧交错带边界判定方法的研究进展》,[J]地理科学进展,2008

10:刘军会、高吉喜、韩永伟、王小亭|《北方农牧交错带可持续发展战略与对策》,[J]中国发展,2008年

11:周锡保|《中国古代服饰史》,[M]中国戏剧出版社,1984年

12:欧文·拉铁摩尔|《中国的亚洲内陆边疆》,[M]江苏人民出版社,2005年

13:斯塔夫里阿诺斯|《全球通史》,[M]北京大学出版社,2005年

14:谭其骧|《中国历史地图集》,[M]中国地图出版社,1996年