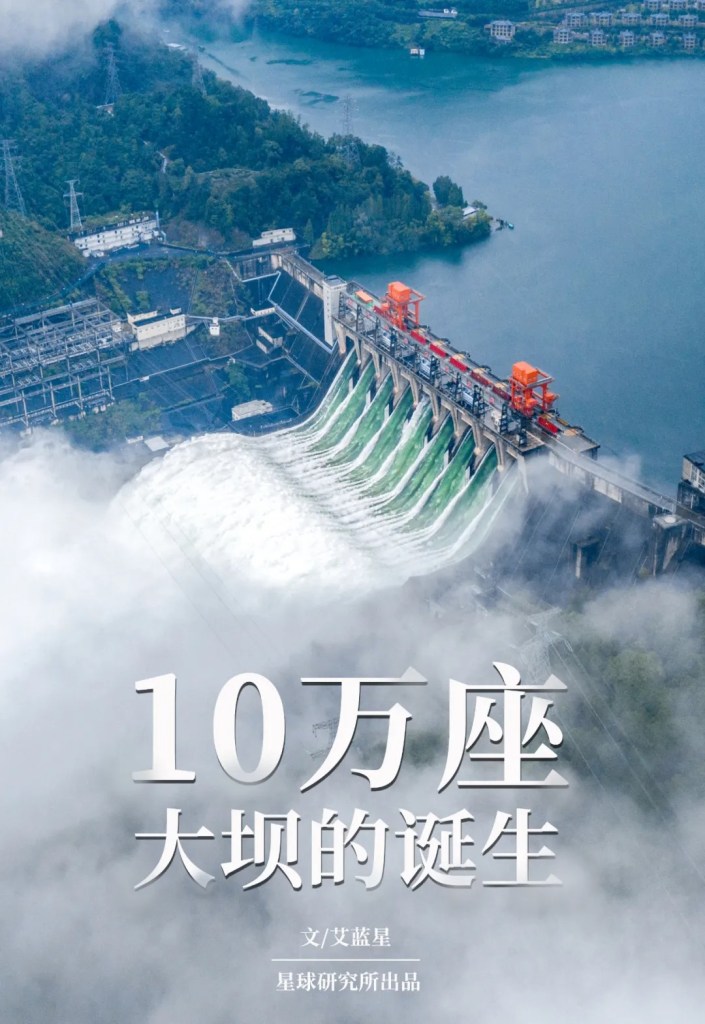

Original piece: 《10万座大坝的诞生!》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 艾蓝星

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

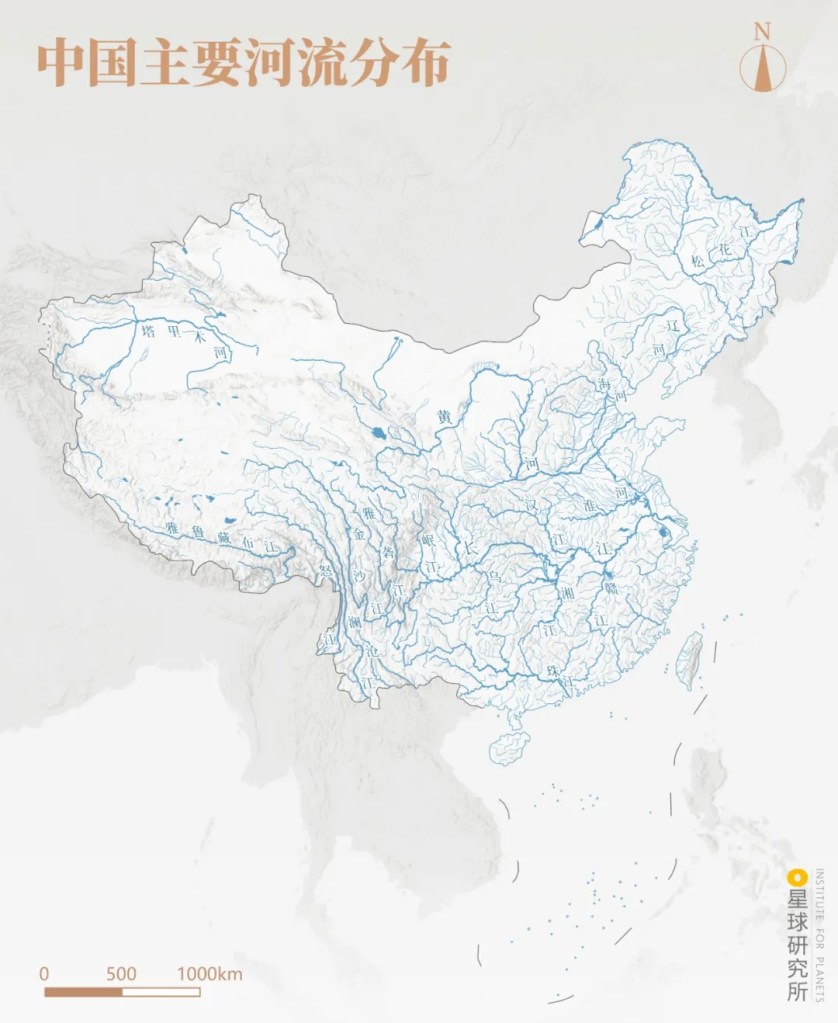

China is one of the countries with most numbers of rivers. More than 45,000 rivers are flowing across this vast nation that spans 9.6 million square kilometres.

The number of rivers stated above only includes those with a drainage area of more than 50 square kilometres

(diagram: 郑艺, Institute for Planets)

China is also one of the countries most frequently hit by water-related disasters. The 1092 floods and 1056 droughts* recorded throughout Chinese history have turned the development of a civilisation into a chronicle of constant war against nature.

*Data as of 1949

(photo: 肖奕叁)

On one hand, rivers nurture every life form they flow by, on the other, they often invite catastrophic events that ruin all livelihood. Faced with such unforgiving characteristics of one of the most elaborate water systems on Earth, China has become by far the most advanced country in large-scale water conservancy facilities in the world.

Among China’s water conservancy projects, the most prominent achievement has to be the 100,000 dams that are capable of retaining almost 900 billion cubic metres of water across the country.

Large dams are defined by the International Commission on Large Dams as any dam above 15 metres in height, or any dam taller than 5 metres with a reservoir capacity of more than 3 million cubic metres

Colour: Dam height above X metres (坝高 X m 以上)

(diagram: 郑艺, Institute for Planets)

They act as a gate to block flood peaks…

(photo: 吕杰琛)

…or a reservoir to provide water supply or irrigation.

It is one of the crucial drinking water sources for cities including Hong Kong and Shenzhen

(photo: 剑胆琴心)

They can also facilitate hydropower generation and streamline shipping channels by raising the water level.

Once completed, it will be the second largest hydropower station in the world after Three Gorges Dam

(photo: 柴峻峰)

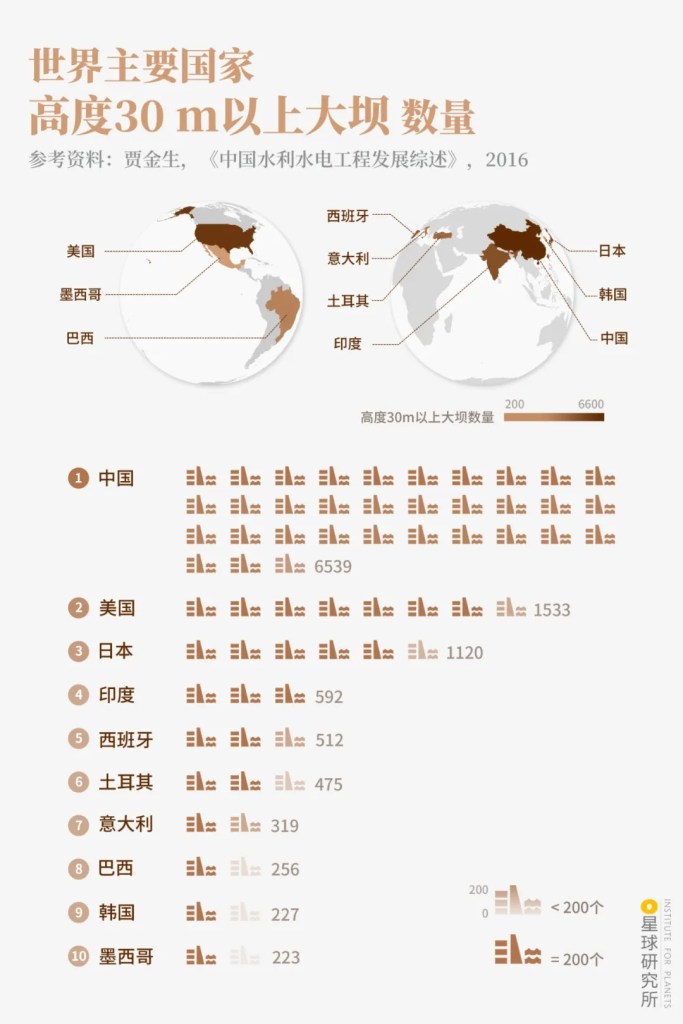

A huge demand is why China has the largest number of dams in the world today.

According to Design Specification for Rolled Earth-Rock Dams (2001), dam bodies can be categorised into low (<30 metres), medium (30-70 metres) and high (>70 metres)

China (中国), United States (美国), Japan (日本), India (印度), Spain (西班牙), Turkey (土耳其), Italy (意大利), Brazil (巴西), South Korea (韩国), Mexico (墨西哥)

(diagram: 郑艺, Institute for Planets)

Ever wonder how were all these dams built?

1. Countering water with earth

To build a dam, one simply needs to excavate earth nearby, pile it up in compact layers and widen the base to trap water coming from upstream. This oldest type of artificial dam is known as earth-filled dams.

This is one of the many types of earth-filled dams

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

The soil particles after compaction are densely crushed within the dam. This stabilises the dam body and at the same time minimises pore sizes between soil particles to limit water seepage. Simple as it may seem, these dams do a good job in achieving what we call “defending assault with soldiers, countering water with earth (兵来将挡,水来土掩)“

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

Given the right conditions, a stable earth dam can be built without any mechanical compaction by merely resting on its own weight*.

*This is known as the filling-soil-into-water method (水中填土法)

This is the first large dam built by filling-soil-into-water method in the world

(photo: 王蒙)

Apart from earth, we can of course use pebbles, sand and artificially mined rocks to build a rock-filled dam. But in contrast to fine earth, rocky materials are rough and hard, making it prone to seepage even with the help from mechanical compaction.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

Engineers therefore combine rock with earth, or erect an earth wall at the centre of a rock-filled dam to stop the seepage. The latter is called earth-core rock-filled dams.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

A classic example of earth-core rock-filled dams; photo shows water coming out through the hydropower station

(photo: 视觉中国)

Or adjust the position to make an inclined core rock-filled dam.

Inclined core (斜墙)

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

The famous 160-metre Xiaolangdi Dam is the tallest inclined core rock-filled dam in China.

The dam embankment is 1667 metres long and 15 metres wide

(photo: 林治坤)

Thanks to this enormous dam, Xiaolangdi Reservoir has a water storage capacity of 12.65 billion cubic metres, which is twice that of Tai Lake. And because of this, the flood control standard in the downstream of Yellow River has now risen to 1000-year floods*, protecting up to 100 million civilians from the lingering menace of floods.

* The term “1000-year flood” means that, based on previous observed data, a flood of this particular magnitude or greater has a 0.1% (1/1000) chance of happening in any given year.

Tai Lake has a storage capacity of 5.6 billion cubic metres

(photo: 张子玉)

Earth is not the only material that can prevent seepage. Concrete can do the same job if not better owing to the even smaller pores. However, compared to the relatively soft and loose earth in rock-filled dams – which might experience mild deformation when compressed by water, concrete is much harder and stronger. This difference in deformation extent limits their ability to ‘cooperate’.

It was not until the 1980s when China finally introduced the vibratory roller, a leading-edge equipment then which was capable of performing enhanced compaction. Much like a giant road roller, it densifies rocky material much more efficiently, hence making the strength and hardness comparable to that of concrete.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Some rock-filled dams also enjoy a concrete buff, which takes only a single layer of concrete panel covering the dam’s upstream face. This is the panel rock-filled dam.

Concrete panel (混凝土面板)

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

This type of low-cost and easy-to-construct dams was a big hit since its introduction in China. The Shuibuya Dam, which is 233 metres tall, seized the throne of the world’s tallest panel rock-filled dam upon completion.

The zigzag track leaning on the dam body is used for drainage, maintenance and transportation

(photo: 李云飞)

The variety of dams mentioned above are collectively known as embankment dams. They are extensively used because of high availability of building materials, simplistic structures and ease of construction. More than 95% of all the 100,000 dams in China are embankment dams. They are literally everywhere.

A classic example of embankment dam without an earth core

(photo: DJY俊逸)

Nevertheless, earth and gravel are after all naturally loose particles, and that sets a glass ceiling for embankment dams.

One one hand, pores exist no matter how strong the compaction process is. Seepage is just a matter of time. On the other, the loose surface of earth and rock materials are unable to withstand the brute force of gushing flood peaks. Therefore, dam overflow has to be avoided at all costs, and a special discharge channel away from the dam body must be installed.

Scroll down to get a feel of a flood discharge at the dam

(photo: 李顺武)

(photo: 谭江弘)

Is it possible to build an even stronger dam?

2. Lone warrior guarding the pass

Imagine placing a rock in the middle of a water stream. The bigger the rock, the heavier it is, and the larger the friction produced between it and the stream bed. Once heavy enough, the friction will be sufficient to nail the rock in the flowing water.

Similarly, if we can manufacture such an enormous rock and throw it in a river, it should be able to hold up the entire river on its own given it is heavy enough. Such a dam is known as gravity dam, which serves like a “lone warrior guarding the final pass where even thousands of enemies are no match for him (一夫当关,万夫莫开)“.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

To that end, strong and dense concrete has returned to the construction menu. Concrete gravity dams can certainly block rivers, but what makes them special is that, due to their superior strength, discharge channels can be installed on the dam body, and in some cases an overflow section can be configured.

Prior to concrete gravity dams, gravity dams were mostly built with lime slurry cemented with stones

(photo: 白䒕帆)

Particularly during flood periods, each of these concrete gravity dams scattered along large rivers becomes a “divine pillar (定水神针)” that serves as the mainstay of flood control measures.

These include the Xiangjiaba Dam which looks after the Jinsha River…

Flood discharge section (泄洪坝段), hydropower station (电站厂房), ship lift (升船机)

(photo: 柴峻峰)

…the Sanmenxia Dam stationed on the Yellow River…

Hydropower station (电站厂房), overflow section (溢流坝), flood and sand discharge channel (泄洪排沙隧道)

(photo: 黄雪峰)

…as well as the Three Gorges Dam that guards the Yangtze River.

With a height of 181 metres and length of 2309 metres, this giant was constructed with more than 16 million cubic metres of concrete. It has a storage capacity of 22.15 billion cubic metres, which is equivalent to 4 Tai Lake combined.

Flood discharge section (泄洪坝段), hydropower station (电站厂房), ship lift (升船机)

(photo: 李心宽)

Since its completion, the Three Gorges Dam has successfully reduced major flood peaks by about 40% during the Yangtze River floods that happened in 2010, 2012 and 2020. This significantly alleviated the burden on the mid- and downstream flood control.

(photo: 李心宽)

But even concrete gravity dams have their own Achilles’ heel – an ‘invisible enemy’ known as uplift pressure. It is comprised of two components: osmotic pressure coming from seepage in the dam body and at the base, as well as the buoyancy experienced by the submerged structures. For a dam, there is nothing worse than being ‘lifted up’ from the base by the uplift pressure.

Water pressure (水体压力), uplift pressure (扬压力)

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

To overcome this issue, engineers have been trying all sorts of methods to strike a balance between stabilising the dam and minimising contact surface between the dam body and the base, for example, by partitioning the dam body into trimmed segments and carving a series of internal cavities. This is known as wide-slit gravity dam.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

It is the first wide-slit gravity dam in China

(photo: 方建飞)

Or simply scoop out the middle section of the dam base to create a hollow gravity dam.

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institue for Planets)

The first hollow gravity dam completed in China is the Shangyoujiang Reservoir Dam in Ganzhou, Jiangxi

(photo: 视觉中国)

Yet even with that settled, there is always something else to worry about. Regardless of the design, the sheer size of a gravity dam will always present a huge challenge to builders, especially for temperature control and construction sequence during concrete pouring.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Rather than backing down from the challenge, engineers came up with a new idea, which is to replace concrete with a special variant that contains fly ash, while incorporating the rolling approach applied in embankment dam compaction to make up for the softer structure. This type of dam is widely known as roller-compacted concrete gravity dams.

This not only reduces concrete usage but also simplifies construction sequence. Furthermore, it makes things more convenient for mechanical construction on a larger scale, and shortens the building time and lowers the cost. This dam type hits multiple birds with one stone.

Completed in 1986, it is the first roller-compacted concrete dam in China

(photo: 三明市大田县融媒体中心)

From then on, more and more grand dams kept rising from the ground, including the Shuikou Dam with a height of 101 metres…

(photo: 视觉中国)

…and the 200.5-metre tall Guangzhao Dam…

A stunning view capturing three mega-projects in one frame

(photo: 王璐)

…as well as the Longtan Dam, currently the tallest roller-compacted concrete gravity dam in the world. Reaching almost 216.5 metres, it is head and shoulders above the Three Gorges Dam, the tallest conventional concrete gravity dam in China.

(photo: 姚王度)

One might wonder, though, if it is possible to achieve even a taller dam height while keeping the building material and costs at acceptable levels. Could there be yet more intricate design for dams?

3. Leveraging the force of nature

On the northern mountains of Guangdong, a thin dam stands majestically in one of the valleys where it curves elegantly upstream in plan. The dam body is so slim that the width-height ratio is only 0.11. This is the well known Quanshui Dam. Located in Shaoguan, Guangdong, it is the thinnest arch dam in China.

(photo: 视觉中国)

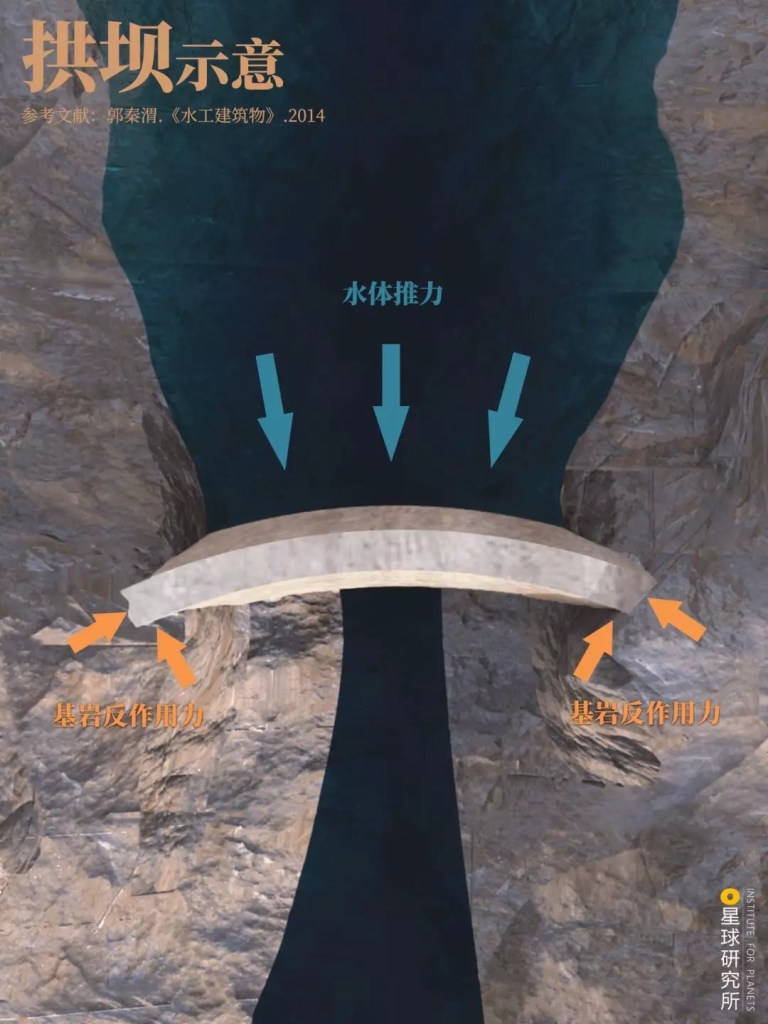

The delicacy of the design resides in its ability to utilise the arched structure, in addition to self weight, for dam stabilisation. In an arch dam, most of the pressure exerted by the water body is passed on to the rigid anchors on the mountain, and the reaction force that pushes back is leveraged to maintain the dam’s stability against the water thrust (借力打力).

Water pressure (水体推力), reaction force from bed rock (基岩反作用力)

(diagram: 罗梓涵, Institute for Planets)

With the mountain sharing the load, arch dams are usually 30-60% smaller in volume than gravity dams of the same height, making them prettier and more economical.

The thinnest section of this lightweight dam is only 7 metres wide

(photo: 姚王度)

More impressively, a functional arch dam maintains a sophisticated balance among multiple factors including self weight, water pressure, bed rock support and temperature changes. If any one of these conditions should fail in the face of unpredictable events, the remaining can still guarantee an intact dam. Such a reliable product is referred to as a statically indeterminate structure.

Arch dams are therefore far superior than other dam types in terms of safety, and their overload capacity can be as high as 10 times the expected performance. For instance, the Shapai Arch Dam in Wenchuan was pretty much unaffected by the deadly 2008 Sichuan earthquake although it was just 36 kilometres away from the epicentre and with a fully loaded reservoir.

(photo: 余振威&刘文君)

While arch dams are beautiful, economical and safe, it is impossible to build one, however, unless all the extremely harsh requirements for topological and geological conditions are met.

Not only do the bed rocks on both banks have to be hard and intact, the river channel must also be symmetrical and contracting in the downstream. All these conditions are absolutely crucial to clip the dam tightly in the valley.

Hydropower station water intake channel (电站厂房进水口), flood discharge channel (泄水孔)

(photo: 卢思璇)

Fortunately, with rapid advancement in construction, building material and simulation technology, the adaptability of arch dams are improving at great speed.

Engineers have successfully built a number of large dams on geologically complex Karst terrains, including the famous Wujiangdu and Goupitan Dams.

(photo: 秦军, 水电八局)

The appearance of arch dams are becoming more diverse too. For example, the Shangli Reservoir Arch Dam in Xiamen Island has a regular arc plane shape.

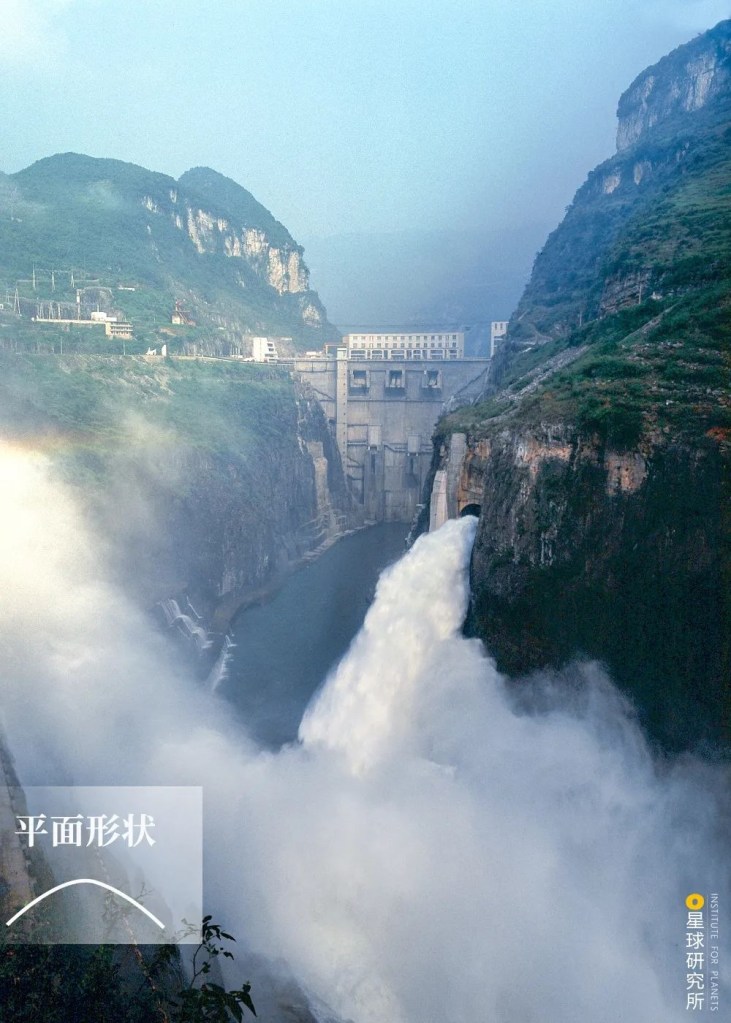

Plane shape (平面形状)

(photo: 视觉中国)

Whereas the Dongfeng Arch Dam on Wu River has a hyperbolic curve.

(photo: 李贵云)

The upstream face of an arch dam can either be vertical, known as single-curved arch dam.

Vertical upstream face (剖面呈竖直), curved plane (平面呈拱形)

(diagram: , Institute for Planets)

Or curving upstream, known as double-curved arch dam.

Curved upstream face (剖面呈拱形), curved plane (平面呈拱形)

(diagram: , Institute for Planets)

Furthermore, new arch dams are growing taller and taller. The 240-metre Ertan Arch Dam, completed in 2000, was the first to exceed the 200-metre mark in China.

(photo: 石磊)

The tallest point of Laxiwa Arch Dam, completed in 2010, is above 250 metres.

(photo: 李俊博)

And the Xiluodu Dam, which came into service in 2014, is 285.5 metres tall.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

Among the 76 large dams that are taller than 200 metres around the globe, 38 were arch dams. They are undeniably the champion of dams. But the 200-metre mark is not even close to their limit.

The Xiaowan Arch Dam on Lancang River is just 5.5 metres away from reaching the 300-metre mark.

Hydropower station water intake channel (电站厂房进水口), flood overflow channel (溢洪道), discharge channel (泄水孔)

(photo: 陈畅)

But the title of world’s tallest dam has to go to Jinping-I Arch Dam sitting on Nyag Qu, which is 305 metres tall.

There are increasing number of towering arch dams rising in the mountainous terrains in western China, where they leverage forces of the nature to store water and mitigate floods, and at the same time generate limitless energy to be delivered to the rest of the country to light up the dark nights.

(photo: 李俊博)

4. One hundred thousand

Across the vast land of China, there are embankment dams that counter water with earth. There are also gravity dams that guard the pass like a lone warrior. And let us not forget the arch dams that leverage the forces of nature. They certainly deserve the spotlight on the great arena, but the big family of Chinese dams is much more than that.

Other outstanding family members include the buttress dams, which has a very minimalistic structure consisting only a set of buttresses and watertight plates…

This is one of the only two multiple-arch buttress dams in China

Buttress (支墩), watertight plate (挡水盖板)

(photo: 视觉中国)

…as well as inflatable rubber dams that can be conveniently summoned to anchor at river channels.

This 1135 metres long rubber dam is the longest of its kind in the world

(photo: 视觉中国)

With current technologies, even the most traditional embankment dams are aiming for new heights. The Nuozhadu Dam, one of such dams completed in 2014, has made it to the 261.5-metre mark…

It is located on Lancang River in Pu’er, Yunnan

(photo: 潘泉)

…while the Shuangjiangkou Dam project, commenced just one year later, intends to redefine the world’s dam height limit with its 314-metre target.

(photo: 杨虎)

One dam at a time, this is how the Chinese have built almost 100,000 of them across the vast territory. They sit in mountains and gate the rivers, courageously guarding all farmlands, villages and cities and every inch of the 9.6 million square kilometres of land.

(photo: 陈剑峰)

Nevertheless, building dams are just the tip of the iceberg of any colossal water conservancy engineering project.

Take the grandiose Three Gorges Dam project, it took more than 40 years of planning and repeated experimentation before the construction could even start. It was not until another 6 years after dam completion when the world’s largest hydropower station could come into service, and 3 more years were needed for the largest ship lift in the world to become ready for use.

(photo: 视觉中国)

The entire Three Gorges Dam project was only fully completed last year in 2020. Now it can finally begin to fulfil its initial purpose as an enormous reservoir, a powerful generator and a grand canal for shipping.

(photo: 黄正平)

This is pretty much the case for every water conservancy project in China, and behind each one of them are the selfless contribution and wisdom of countless engineers and builders, without which the engineering wonder of Chinese dams could not have been created.

(photo: 行影不离)

Production Team

Text: 艾蓝星

Photos: 散夏

Design: 罗梓涵

Maps: 郑艺

Review: 桢公子,黄超

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Sinohydro Engineering Bureau 8 Corp Ltd for their immense support with graphical content, as well as Prof Ma Jiming (School of Civil Engineering, Tsinghua University) and Dr Zhang Lei (Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences) for their intellectual contribution.

References

[1] 王瑞芳. 当代中国水利史[M]. 中国社会科学出版社, 2014.

[2] 郭秦渭. 水工建筑物[M]. 重庆大学出版社, 2014.

[3] 潘家铮. 千秋功罪话水坝[M]. 清华大学出版社, 2000.

[4] 贾金生. 中国大坝建设60年[M]. 中国水利水电出版社, 2013.

[5] 水利部建设与管理司. 中国高坝大库TOP100[M]. 中国水利水电出版社, 2012.

[6] 水利部. 2018年全国水利发展统计公报.

[7] 水利部. 2013年第一次全国水利普查公报.

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光