Original piece: 《30000座隧道的诞生!》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 艾蓝星

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

Punching through the mountains

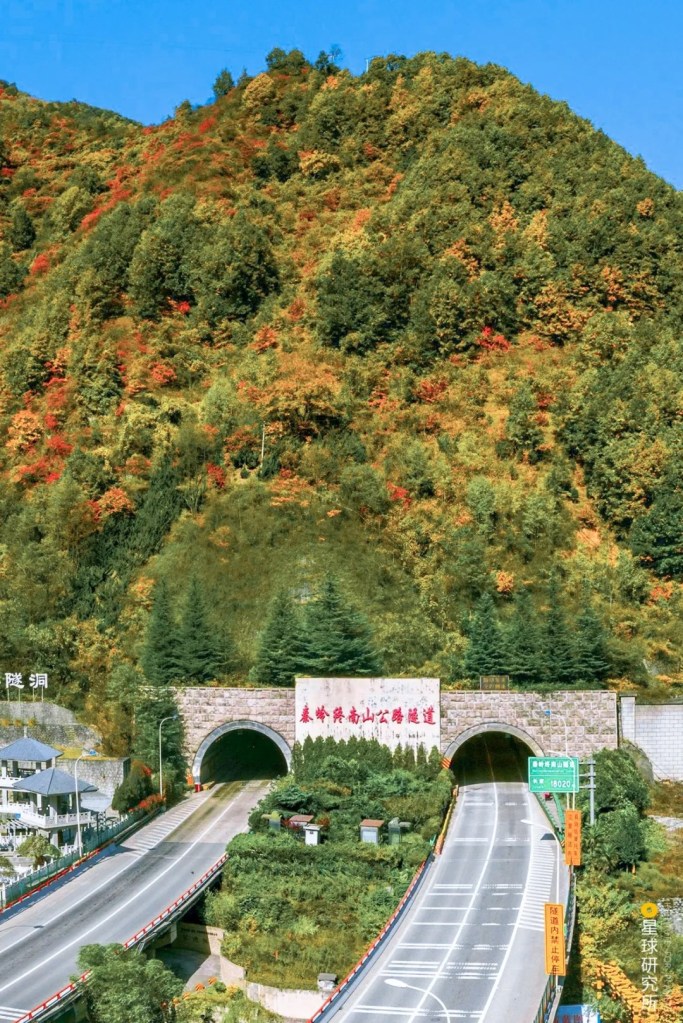

If you hike the Qin Mountains, you would be standing above 7 enormous tunnels, each stretching more than 10 kilometres through the rolling peaks. The longest among them is a 18-kilometre highway tunnel, which takes 15 minutes to drive through at the 70 km/h speed limit.

Xi’an-Ankang Railway Qinling Tunnel (西康铁路秦岭隧道), 18456 m

Qinling-Zhongnanshan Highway Tunnel (秦岭终南山公路隧道), 18020 m

Qianyou-Shibianyu Water Transfer Tunnel (引乾济石调水隧洞), 18040 m

(photo: 魏炜)

Go to Guizhou and you would be stepping on more than 1400 tunnels, which have pretty much turned the underground of the entire province into a beehive. The Guiyang-Guangzhou High-speed Railway, which has a total length of 857 kilometres, spends more than half of its travel underground. It is more like an inter-provincial metro line than a conventional railway.

(photo: 刘慎库)

And don’t even bother to visualise what lies beneath the entire country. Under the vast Chinese territory spanning 9.6 million square kilometres, there is a massive transportation network comprised of more than 35,000 tunnels that are operating round the clock for passengers and freight travelling all over the country. This tunnel network, totalling up to approximately 37,000 kilometres in length, is almost capable of running around the equator once. It is by far the longest tunnel network in the world and, impressively, the majority of it was completed within the 4 decades following the reform and opening up policy.

This piece focuses only on railway and highway tunnels in mountain areas, excluding city and underwater tunnels

(diagram: 陈志浩&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

From Loess Plateau to Taiheng Mountains…

(photo: 王伟光)

…and from Tibetan Plateau to Tengri Tagh…

(photo: 沈龙泉)

…tunnels have been gradually transforming this mountainous country.

How did the Chinese manage to build each and every one of these tunnels?

1. The birth of a tunnel

There are countless types of tunnels in China. Some run along the mountainside, and are covered by artificial ceilings throughout the way. These are known as shed tunnels or open-cut tunnels.

(photo: 张普超)

Others hang by the cliffs where tunnel windows are carved out from the rocks. These are the cliff-hanging highways.

(photo: 石耀臣)

They can also be part of a highway that spirals around the slopes, going in and out of the hills and forming a terrace-like landscape.

Quiz: how many tunnel entrances are there?

(photo: 沈龙泉)

But tunnels are more often hidden in the deep mountains, exposing only the narrow tunnel portal. Usually, tunnel portals have upright walls with a crude design.

Tunnel portals with an upright wall structure is called end wall tunnel portals, which are the most common design

(photo: 李昌华)

Sometimes they are decorated with pillars on the sides, making them prettier and more stable.

(photo: 赵斌)

Those that merge into the surroundings best are the bamboo-truncating tunnel portal. As its name suggests, it looks like a bamboo neatly cut open along the mountain slope.

(photo: 沈龙泉)

Another type of tunnel portal with a special appearance is mostly used for high-speed railway tunnels, where it exhibits a bell-mouth shape facing out. When a train passes through a tunnel portal at high speed, the compressed airflow will produce strong shock pressure, which generates loud noise or causes discomfort in passengers. A bell-mouth tunnel portal buffers such disturbances much better than others.

(photo: 田卓然)

Once through the portal, one will be travelling along an unobstructed passage in the tunnel, either in total darkness…

(photo: 李昌华)

Or in a brightly lit interior.

(photo: 沈噌噌)

But before tunnels can become a smooth ride, they have to undergo several transformations.

First of all, builders have to drill, blast and excavate a way out of the mountain body. Rock drilling rigs are used to drill into the rocks at the initial construction site. Multiple holes are drilled at carefully determined depth and position, so that precise amount of explosives can be placed appropriately for controlled detonation.

Blasting is currently the most commonly used and most mature approach for mountain tunnels

(photo: 视觉中国)

Blasting with high precision makes it possible to excavate a desired tunnel contour while leaving behind a rather smooth rock wall.

Blast marks (炮痕) and desired tunnel contour (预设轮廓)

(photo: 李锦勇)

Second, to prevent the tunnel from collapsing after the blast, engineers have to set up a structure support. In the past, this was done using wood or steel, and now, they have come up with a better idea*: anchor rods are first inserted into the rock walls, then a ring of steel mesh is overlaid on top, followed by concrete spraying to fix the structure and avoid deformation of the rock wall.

*This method was first proposed by Ladislaus von Rabcewicz, an Austrian engineer and university professor, and was later given an official recognition at the International Conference on Soil Mechanics as the New Austrian Tunnelling Method, or NATM.

Steel mesh (钢筋网), shotcrete (喷射混凝土)

(photo: 视觉中国)

It has been extensively applied since its introduction in China in the 1970s.

Quiz: how many builders are there?

(photo: 牛荣健)

Apart from stabilising the tunnel structure, a waterproof layer is added to the tunnel interior to prevent seeping.

Waterproof seal (隔水层)

(photo: 靳晰)

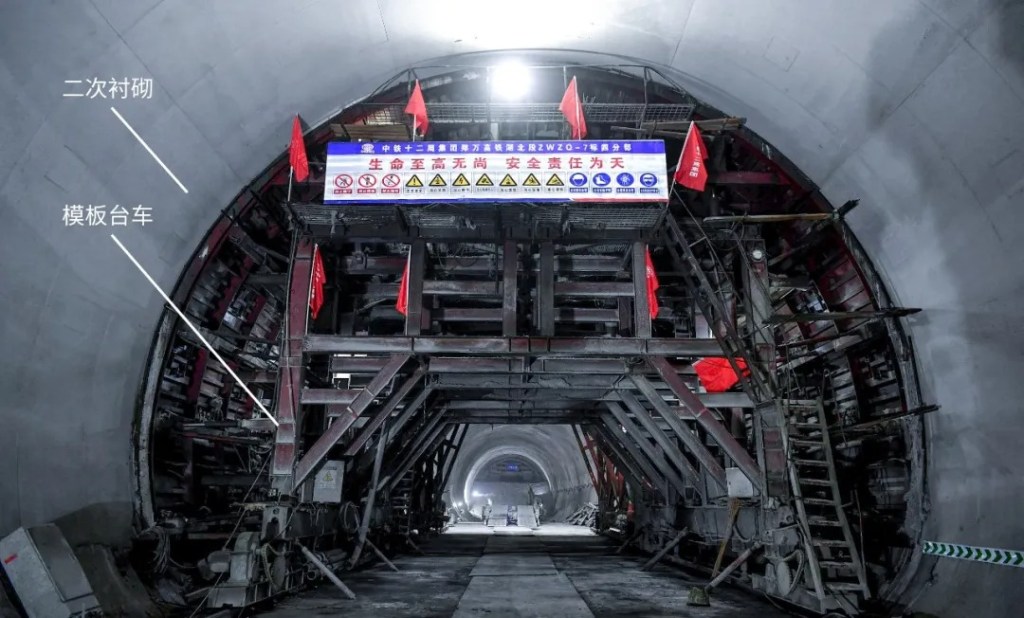

The third transformation requires a formwork trolley, where concrete is used to fill up the space between the formwork and the waterproof wall. This further consolidates the tunnel and prettifies the interior with a neat and smooth surface, known as the second lining of the tunnel.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Following the installation of ventilation and lightings, a brand new tunnel is finally completed.

(photo: 王利)

Tunnels facilitate communication between those separated by natural barriers. This is best exemplified by Baoji-Chengdu Railway completed in the 1950s, which was the first railway ever to bridge between northwest and southwest regions of China. About 80% of the entire route is embedded in towering mountain ranges, but traversing these Qin Mountains was made possible by building a total of 304 tunnels. The ‘unforgiving journey into Sichuan (蜀道难)’ has since become history.

(photo: 武嘉旭)

However, owing to technical limitations then, most tunnels along the Baoji-Chengdu Railway were not longer than 1000 metres, and the longest one stretched only about 2300 metres. While the tunnel cluster forms a breathtaking scenery not seen elsewhere, trains climb extremely slowly through them, despite getting extra help from spirals*. The operating speed and freight capacity of this railway is far from satisfactory.

Therefore, we need longer tunnels, much longer ones.

*For a train to reach a given elevation, the railway will have to be elongated for a gradually climb, these are called spirals.

Terminal stations: Guangyuan (广元), Baoji (宝鸡)

Stations: Qinling Station (秦岭站), Qinling Tunnel (秦岭隧道), Qingshiya Station (青石崖站), Guanyinshan Station (观音山站), Yangjiawan Station (杨家湾站)

Yellow: spiral rail (盘山铁路); shade: tunnel (穿山隧道)

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

2. Make it longer!

The longest railway tunnel in China back in the 1950s was the 4270-metre Liangfengya Railway Tunnel.

(photo: 张普超)

Then by 1960s, the Yimaling Tunnel first exceeded 7000 metres. Two decades later, the 14,295-metre Dayaoshan Tunnel opened in 1988 became the first tunnel to cross the 10,000 metres mark, and was once the longest two-way electrified railway tunnel.

(photo: 管俊鸿)

The next milestone was the 20,000-metre Wushaoling Tunnel completed shortly after the arrival of the 21st century.

The tunnel is part of the Lanzhou-Wuwei Railway, which is an indispensable component of the New Eurasian Continental Bridge of the eight-vertical-eight-horizontal railway network. It is a key route linking the western regions (e.g. Xinjiang) to the rest of China

(photo: 张一飞)

As of 2019, there were 16,084 railway tunnels in China, totalling more than 18,041 kilometres in length. Among them, the longest one has already exceeded 32,000 metres.

According to Code for Design of Railway Tunnel 2016, railway tunnels are categorised, based on length, into short (≤500 m), medium (500-3000 m), long (3000-10000 m) and extra long (>10000 m) tunnels

1. New Guanjiao Tunnel (32690 m, 新关角隧道), 2. West Qinling Tunnel (28236 m, 西秦岭隧道), 3. Taihangshan Tunnel (27839 m, 太行山隧道), 4. South Lüliangshan Tunnel (23443 m, 南吕梁山隧道), 5. Xiaoshan Tunnel (22751 m, 崤山隧道), 6. Middle Tianshan Tunnel (22449 m, 中天山隧道), 7. Qingyunshan Tunnel (22175 m, 青云山隧道), 8. Yanshan Tunnel (21153 m, 燕山隧道), 9. Lüliangshan Tunnel (20785 m, 吕梁山隧道), 10. Dangjinshan Tunnel (20100 m, 当金山隧道), 11. Wushaoling Tunnel (20050 m, 乌鞘岭隧道)

(diagram: 陈志浩&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

And for highway tunnels, there were already 19,067 of them with a total mileage of 18,966 kilometres. The 18,020-metre Qinling-Zhongnanshan Tunnel is currently the champion of all highway tunnels in China.

According to Technical Standard for Highway Engineering 2014, highway tunnels are categorised into short (≤500 m), intermediate (500-1000 m), long (1000-3000 m) and extra long (>3000 m) tunnels

(photo: 魏炜)

With long and extra long tunnels coming into service, all those curly and winding mountain roads can finally be straightened and shortened. Painful spirals are replaced by a tunnel running through the mountain base.

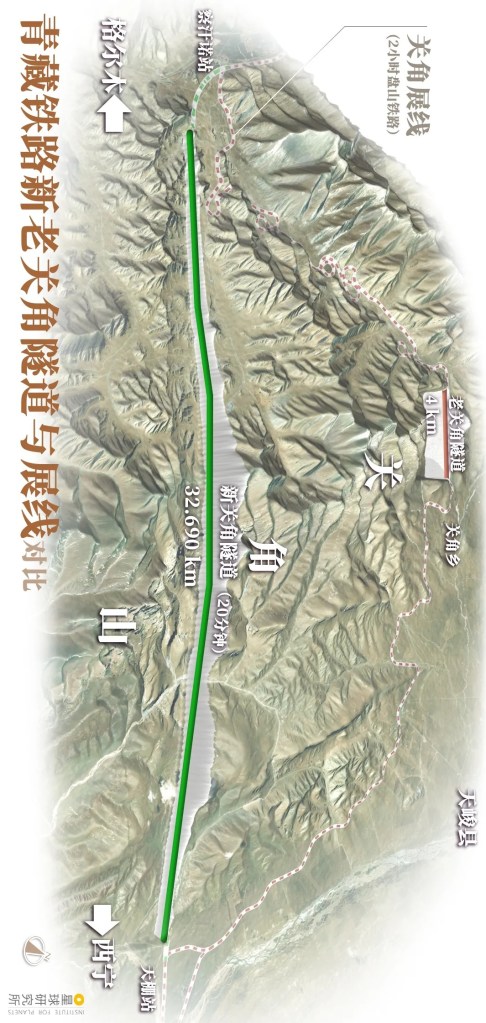

Take the Qinghai-Tibet Railway completed in the 1970s, to go past the Guanjiao Mountain, trains had to first climb 600 metres on a spiral track before reaching the 4200-metre Old Guanjiao Tunnel, and then come out and slowing spiral down the mountain on the other side. That alone used to take 2 hours.

(photo: 王璐)

In 2014, a 32-kilometre extra long tunnel found its way through the Guanjiao Mountain. The same journey now takes only about 20 minutes, more importantly, it avoids potential snow storms or other terrible weathers on the mountain.

Guanjaio Mountain (关角山), Guanjiao Spiral — 2-hour spiral railway (关角展线–2小时半山铁路)

Destinations: Golmud (格尔木), Xining (西宁)

Stations or towns: Chahannuo Station (察罕诺站), Guanjiao Village (关角乡), Tianjun County (天峻县), Tianpeng Station (天棚站)

(diagram: 陈志浩, Institute for Planets)

So, how are these convenient long and extra long tunnels built?

Usually, shorter tunnels are excavated from both ends. But this obviously will be extremely inefficient for long ones.

(photo: 文林)

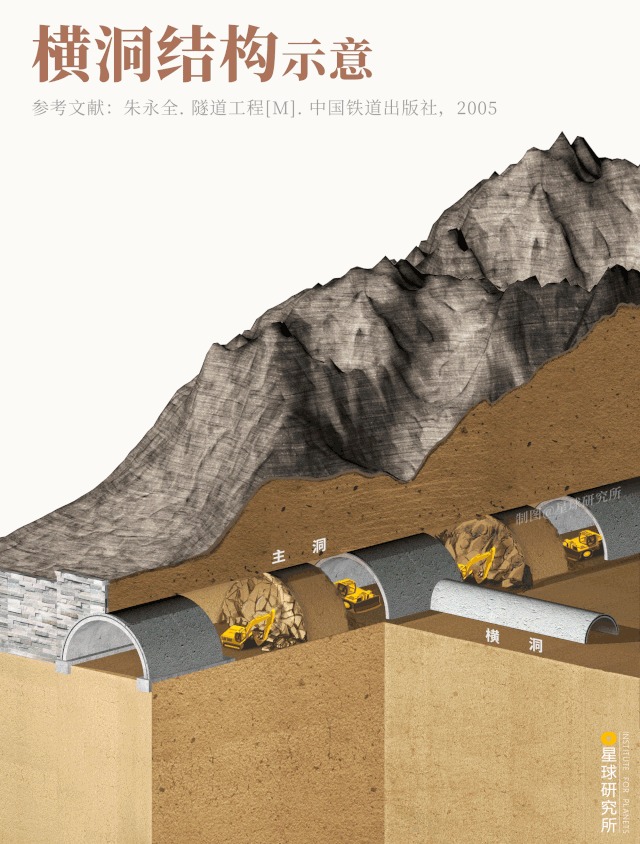

Instead, builders partition long tunnels into shorter segments and work on multiple segments simultaneously, an approach commonly known as sectioned construction. They first identify a spot on the ground surface that is relatively close to the tunnel to be built, and drill a channel from there towards the tunnel. This cross channel allows builders and equipments to enter from the side and start construction at the segment.

Main tunnel (主洞)

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

If the tunnel is embedded too deep into the mountain body, a shaft can be drilled from above where the ground layer is relatively thin. These shafts can be vertical or slanted.

(diagram: Institute for Planets)

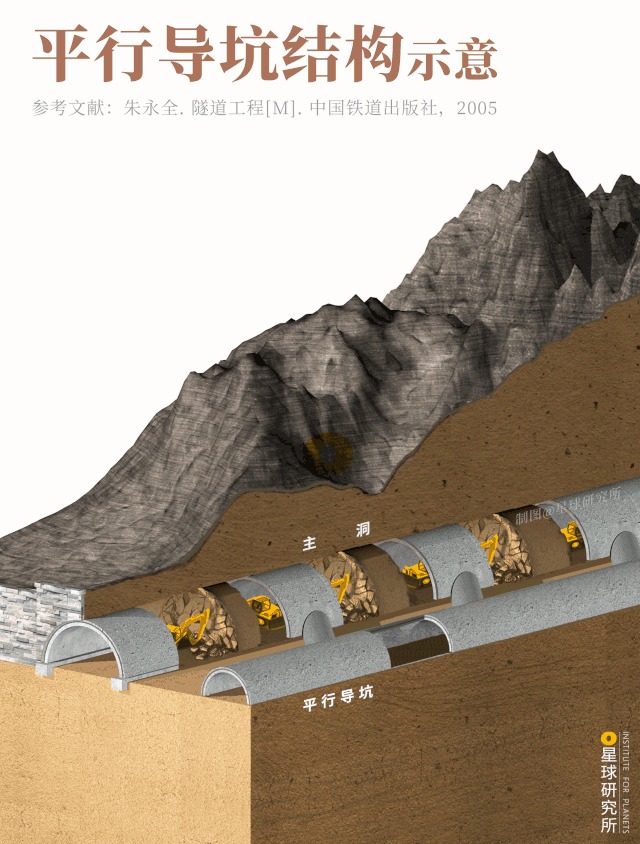

Once cross channels and shafts are in place, construction efficiency will be greatly improved with simultaneous construction fronts. But when faced with complex situations in the mountains, parallel heading is still the best approach. In this case, a channel in parallel to the main tunnel is built as a primer for geological assessment, at the same time cross channels can reach out to the main tunnel from the parallel heading to create yet another two construction fronts, further maximising the construction efficiency.

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

Occasionally, parallel headings are converted into a functional tunnel after expansion and with proper lining, just like the Qinling Second Tunnel of the Xi’an-Ankang Railway.

(photo: 熊可)

All these technologies lay the foundation for the construction of tens of thousands of tunnels. However, building tunnels is still not straight forward given the immense diversity in geological conditions across China, as well as the complicated underground working environment. Builders have no choice but to work smart.

3. Challenges

8 August 2008.

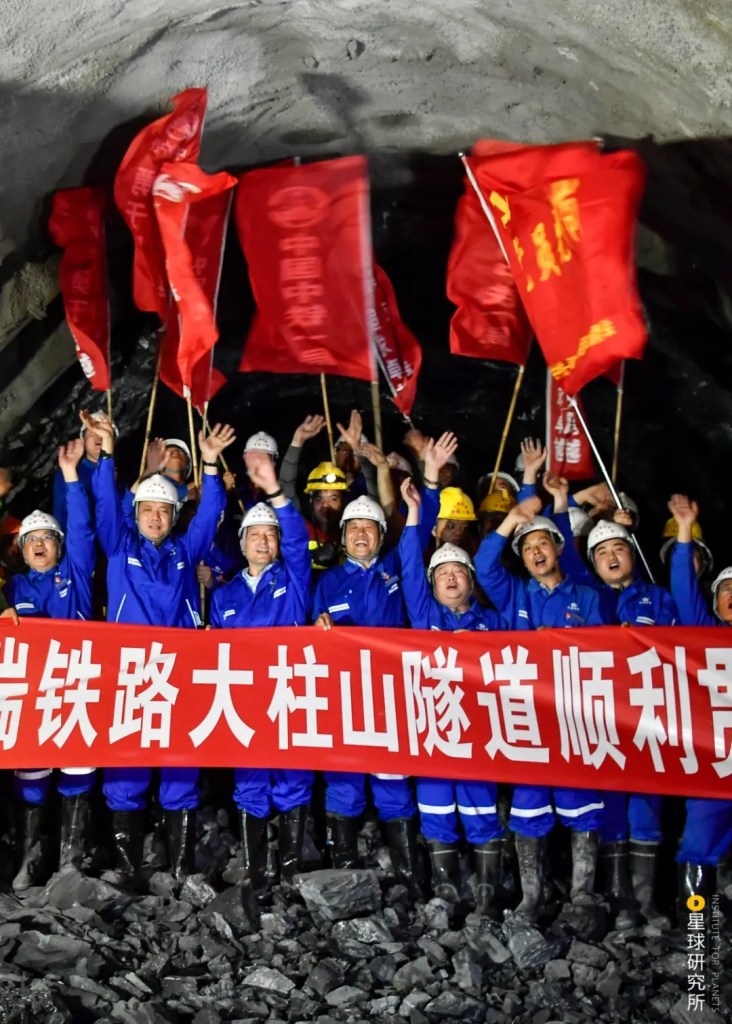

Beijing was enjoying all the attention from the entire world for the Olympic opening ceremony. Few knew that thousands of miles away beside the Lancang River, the construction of Dazhushan Tunnel quietly commenced on the same day.

It is a 14.5-kilometre tunnel that is part of the Dali-Ruili Railway. It was expected to be completed within 5.5 years, but the construction difficulty far exceeded expectation, resulting in repeated delays. The excavation was at long last finished on 28 April 2020.

(photo: 牛荣健)

Why did it take 12 whole years to excavate just one tunnel?

The key to answering this question lies in the complex topography and geology of China. In fact, building tunnels here is anything but easy.

(diagram: Institute for Planets)

In the northwest, the land surface of Loess Plateau is shabby and extremely wrinkly with interlaced valleys and gorges. Loess soil is soft and prone to collapse, hence sinking is not uncommon on a wet day.

(photo: 李楷行)

The Zhengzhou-Xi’an High-speed Railway, launched in 2005, travels through exactly these terrains, and not just once but multiple times. The 8483-metre Zhangmao Tunnel located at the Sanmen Gorge in Henan is the longest tunnel in the entire route. With a planned excavation section of more than 160 square metres, it is the widest loess tunnel in the world.

(photo: 张一飞)

When doing work within the soft loess layers, it is crucial to minimise even the tiniest disturbances to prevent the sizeable tunnel from collapsing. Builders therefore pioneered a unique method known as the three-bench seven-step excavation method, where the excavation section is partitioned vertically into three benches and further compartmentalised into seven subsections for steady excavation.

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

The karst regions in the south are predominantly overlain by carbonate rock layers which, after persistent dissolution, have become utterly fragmented.

(photo: 黄一骏)

And below the undulating landscape are extensive networks of sinkholes and underground rivers. Though magnificent, these sceneries pose great challenges to tunnel construction.

(photo: 无影)

Builders quite often drill into one of those, which greets them with gushes of water or mud. For instance, Nanling Tunnel in Chenzhou, Hunan, runs right through a dense network of sinkholes. During construction, a total of 24 incidents of water inrush and mud gushing were recorded, and one of the mud gushes exceeded 8000 cubic metres in volume, which blocked 117 metres of the tunnel.

(photo: 史飞龙)

At other times, builders encounter enormous sinkholes, so deep that they need to bridge the tunnel across. A classic example is the Xiazihe Tunnel of Sichuan-Guizhou Railway, which needed a 27.7-metre bridge to span such a sinkhole. Before this, building bridges in a cave was simply beyond imagination.

(photo: 视觉中国)

On the icy Tibetan Plateau where the average elevation is above 4000 metres, air is scarce and the climate is brutal.

(photo: 刘珠明)

Here, water that seeps into cracks on the ground freezes and expands as temperature drops, and melts when it becomes warmer, thereby causing collapse of the ground layer. A repeating freeze-thaw cycle greatly increases risks of cracking in the tunnel structure.

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

A reliable waterproof design is therefore indispensable to minimise the effects of ambient temperature on the tunnel structure. In addition, insulating layers are added to maintain a stable temperature inside the tunnel.

One of these tunnels is the Kunlun Mountain Tunnel of Qinghai-Tibet Railway opened in 2002. It took one whole year of non-stop experiments and testing before this rather short (1686 metres) yet cold-resistant tunnel was able to travel through the permafrost sitting at 4600 metres above sea level.

(photo: 视觉中国)

Not to mention that all builders needed extra oxygen supply for working at high altitudes.

(photo: 牛荣健)

But when it comes to construction difficulties, even the loess surface, rock dissolution and permafrost are nothing compared to faults of all sizes. The worst faults are those with abundant underground water, because the fragmented and inrush-prone ground layers are almost impossible to work in. They are the infamous ‘rotten caves’.

The Dazhushan Tunnel, for example, traverses 6 major faults. It took almost 26 months to make it through one of the high-pressure faults that spans 156 metres, that is a 20-centimetre excavation per day.

(photo: 史飞龙)

Builders spent more time pumping out water than actually building the tunnel. The constant outflow of water from the cave mouth created an artificial waterfall.

Main tunnel (主洞), parallel heading (平行导坑)

(photo: 赵子忠)

Concerns for complex geological conditions are not just about technical challenges, but also terrible working environment that haunts every builder. That is why when working in gas-bearing strata, including coal seams and oil shale, tunnels have to be well ventilated to dilute the toxic gas constantly building up.

(photo: 陈畅)

Apart from gas, dust produced during construction and transportation is another major pollutant in tunnels that warrants more efficient ventilation systems, especially when the excavation is going deeper and open space is reducing rapidly.

(photo: 陈畅)

Moreover, in the Sangzhuling Tunnel of Sichuan-Tibet Railway, tunnel temperatures can shoot up to 89.3°C. Builders must cool themselves down using giant ice cubes.

(photo: 牛荣健)

All these scenarios are just tip of the iceberg for what tunnel builders in China face every day. Nevertheless, they are determined to overcome any barrier at all costs.

(photo: 牛荣健)

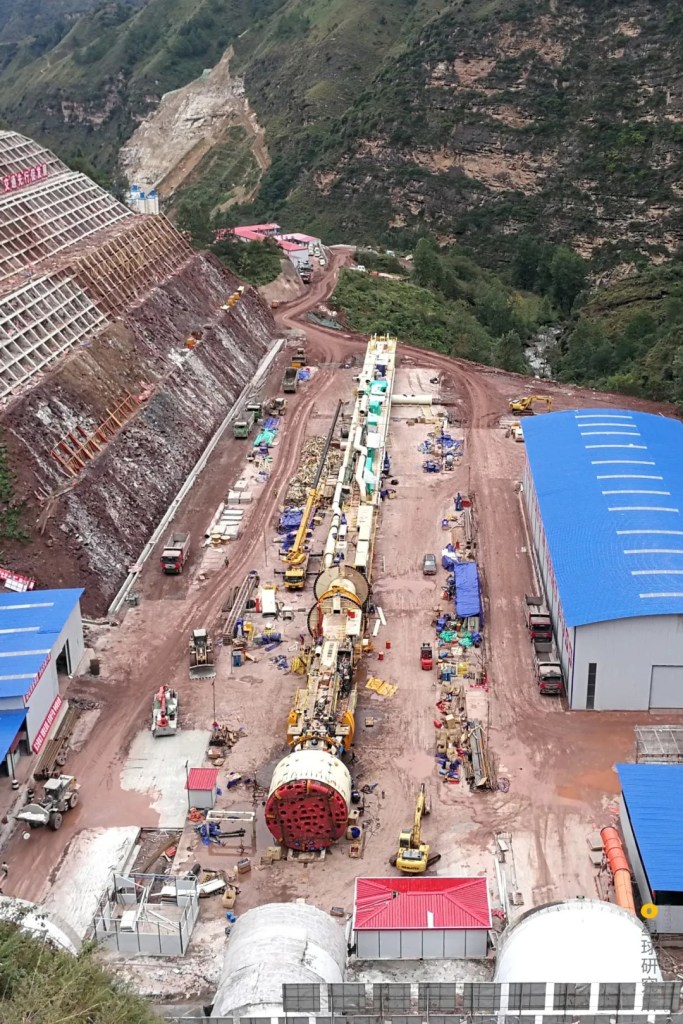

Engineers are also a major driving force in breaking these barriers, as they continuously innovate new technologies and develop novel tools. One of these is of course the tunnel boring machine. These giant monsters can be several hundred metres across, so big that they can hardly be fit in a standard football pitch. Currently the most advanced tunnel excavating tool, tunnel boring machines possess powerful claws (rotating cutterheads) that fracture and chip away rocks in front of them much more efficiently compared to any other mechanical system.

China has to date autonomously developed the Yuecheng-Liangshan and Caiyun models, among other tunnel boring machine models, and everyday there are more autonomous equipments joining in the mechanised tunnel excavation.

(photo: 贺锐)

The Chinese could not have punched through the mountains without the wisdom and concerted efforts of numerous hardworking engineers and builders.

Tunnels are by the minute breaking all geographical barriers and connecting every corner in China together, be it on the Tibetan Plateau…

(photo: 在远方的阿伦)

Or the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau…

(photo: 谭江弘)

They assimilate into the Taiheng landscape…

(photo: 邓国晖)

Side with rivers…

(photo: 姜曦)

And dance with the Great Wall.

(photo: 姚金辉)

In 2010, a tunnel made it through the Galongla Snow Mountain, and was followed by the completion of Motuo Highway in just three years. Motuo county, the very last and only county long forgotten by China’s highway network, finally joined the club.

(photo: 李贞泰)

The Gaoligong Mountain Tunnel, longest in Asia (34.5 kilometres) and still under construction, will reduce the travel time between Dali and Ruili by at least half.

City: Dali (大理), Ruili (瑞丽)

Station: Nu River Station (怒江车站), Longling Station (龙陵车站)

(diagram: 王申雯, Institute for Planets)

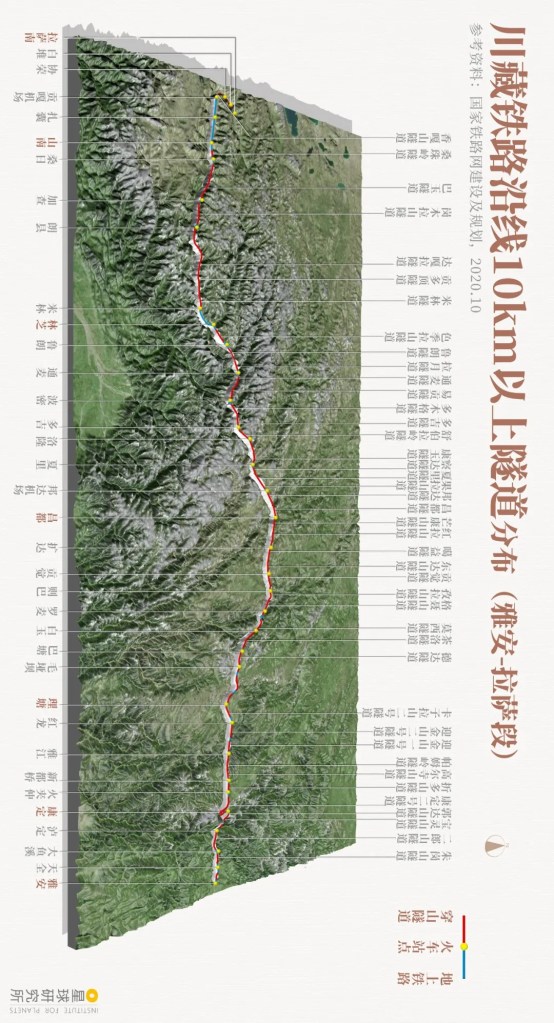

The route planning for the entire Sichuan-Tibet Railway was approved towards the end of September, 2020. There will be 21 tunnels sitting at 4000 metres above sea level, and 72 more scattered along the Ya’an-Nyingchi section, totalling 838 kilometres and 83% of the entire route. Almost like a metro line running through the Hengduan Mountains and Tibetan Plateau, the Sichuan-Tibet Railway will be the second heaven’s road into Tibet (进藏天路) after the Qinghai-Tibet Railway.

Route colour: red, tunnels (穿山隧道); yellow, train stations (火车站点); blue, aboveground railway (地上铁路)

Stations (below): Lhasa South (拉萨南), Baidui (白堆), Xêrong (协荣), Gonggar Airport (贡嘎机场), Chanang (扎囊), Shannan (山南), Sangri (桑日), Gyaca (加查), Nang County (朗县), Mainling (米林), Nyingchi (林芝), Lulang (鲁朗), Tongmai (通麦), Bomê (波密), Dojie (多吉), Lhorong (洛隆), Gyari (夏里), Bamda Airport (邦达机场), Chamdo (昌都), Korra (扩达), Gonjo (贡觉), Zêba (则巴), Langmai (罗麦), Baiyu (白玉), Batang (巴塘), Maoyaba (毛垭坝), Honglong (红龙), Yajiang (雅江), Xinduqiao (新都桥), Huojiazhong (火夹仲), Kangding (康定), Luding (泸定), Dayuxi (大鱼溪), Tianquan (天全), Ya’an (雅安)

Tunnels (above): Sianggashan Tunnel (香嘎山隧道), Sangzhuling Tunnel (桑珠岭隧道), Bayu Tunnel (巴玉隧道), Gangmula Mountain Tunnel (岗木拉山隧道), Dagala Tunnel (达嘎啦隧道), Gongduoding Tunnel (贡多顶隧道), Mainling Tunnel (米林隧道), Shergyla Mountain Tunnel (色季拉山隧道), Lulang Tunnel (鲁朗隧道), Layue Tunnel (拉月隧道), Tongmai Tunnel (通麦隧道), Yigong Tunnel (易贡隧道), Duomuge Tunnel (多木格隧道), Dojie Tunnel (多吉隧道), Baxoi La Mountain Tunnel (伯舒拉岭隧道), Kangyu Tunnel (康玉隧道), Chada Tunnel (察达隧道), Gyari Tunnel (夏里隧道), Guolashan Tunnel (郭拉山隧道), Bamda Tunnel (邦达隧道), Chamdo Tunnel (昌都隧道), Mangkangshan Tunnel (芒康山隧道), Honglashan Tunnel (红拉山隧道), Gayi Tunnel (噶益隧道), Dongdashan Tunnel (东达山隧道), Gonjo Tunnel (贡觉隧道), Zilashan Tunnel (孜拉山隧道), Genyen Tunnel (格聂山隧道), Moxi Tunnel (莫西隧道), Chaluo Tunnel (茶洛隧道), Deda Tunnel (德达隧道), Kazila Mountain Second Tunnel (卡子拉山隧道), Yingjin Mountain Second Tunnel (迎金山二号隧道) and First Tunnel (迎金山一号隧道), Pamuling Tunnel (帕姆岭隧道), Gao‘ersishan Tunnel (高尔寺山隧道), Zheduoshan Tunnel (折多山隧道), Kangding Second Tunnel (康定二号隧道), Guodashan Tunnel (郭达山隧道), Baolingshan Tunnel (宝灵山隧道), Erlangshan Tunnel (二郎山隧道), Zhugangshan Tunnel (朱岗山隧道)

(diagram: 陈志浩&王申雯, Institute for Planets)

As such, more than 37,000 kilometres of tunnels are boring through this land, and the network will only keep growing. Within the window of several decades, an entire country home to 1.4 billion people has become interconnected, and fully ready to stride into the future.

Years may rush by, but this part of history will always be the golden age of Chinese railway never to be forgotten.

Production Team

Text: 艾蓝星

Photos: 隧觉觉

Design: 王申雯

Maps: 陈志浩

Review: 黄超、云舞空城、王长春

Expert review

Prof. Wang Shuying, School of Civil Engineering, Central South University (王树英 教授, 中南大学土木工程学院)

Dr. Zhou Xiaohan, School of Civil Engineering, Chongqing University (周小涵 博士, 重庆大学土木工程学院)

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to China Railway First Group Co. Ltd. and CINCT (基建通) for their immense support.

References

[1] 《中国铁路隧道史》编纂委员会. 中国铁路隧道史[M]. 中国铁道出版社, 2004.

[2] 吕康成. 特殊隧道工程[M]. 人民交通出版社, 2013.

[3] 朱永全. 隧道工程[M]. 中国铁道出版社, 2015.

[4] 2019年交通运输行业发展统计公报.

[5] 田四明. 截至2019年底中国铁路隧道情况统计[J]. 隧道建设, 2020.

[6] 《中国公路学报》编辑部. 中国隧道工程学术研究综述[J]. 中国公路学报, 2015.

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光