Original piece: 《15%的中国》

Co-produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所) & Mutian Book Donation Charity Project (幕天捐书公益项目)

Written by Institute for Planets

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

Destitution in Scenic Areas

Translator’s comment:

This piece was originally published (in Chinese) 2 years ago in July 2018. According to China’s 13th Five-year Plan, extreme poverty in the country is to be eliminated this year (2020). Since 1978, the government has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, and the continuous work of poverty alleviation has intensified as the ‘deadline’ approaches. Here, from a geographical perspective, let’s take a look at some of the major obstacles that were still lying ahead of China’s final sprint for poverty alleviation.

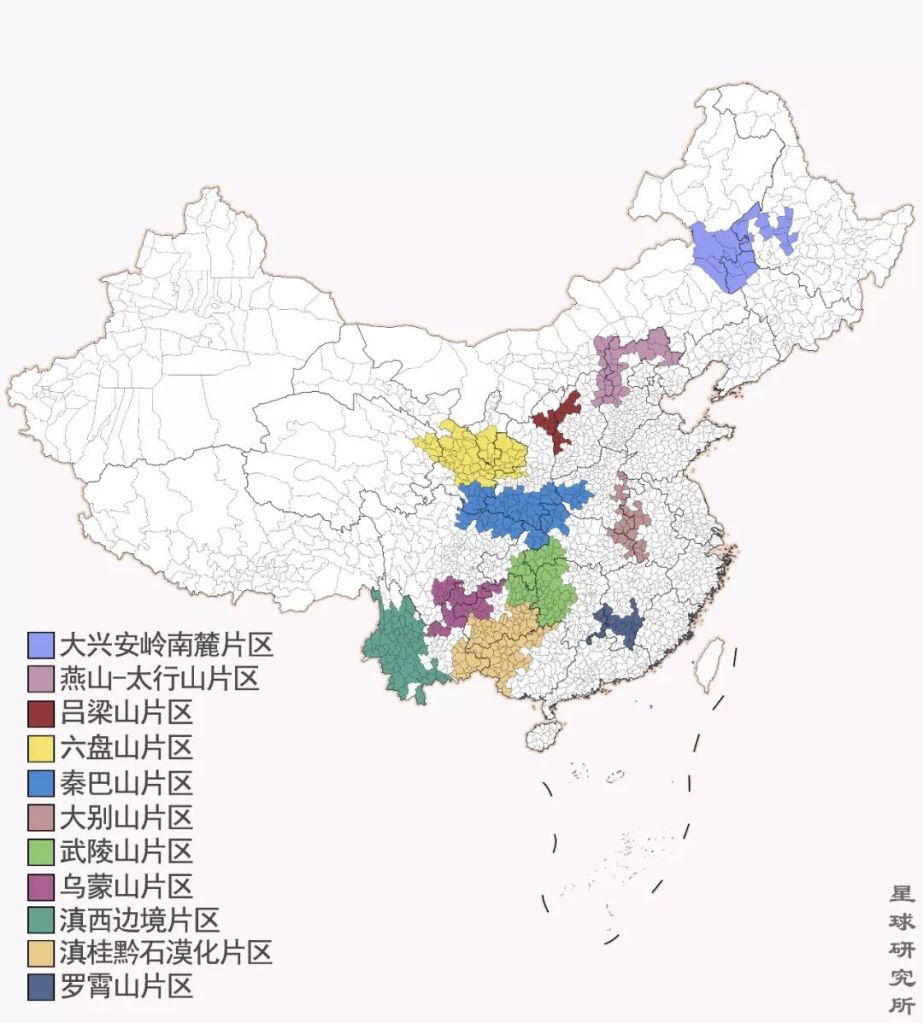

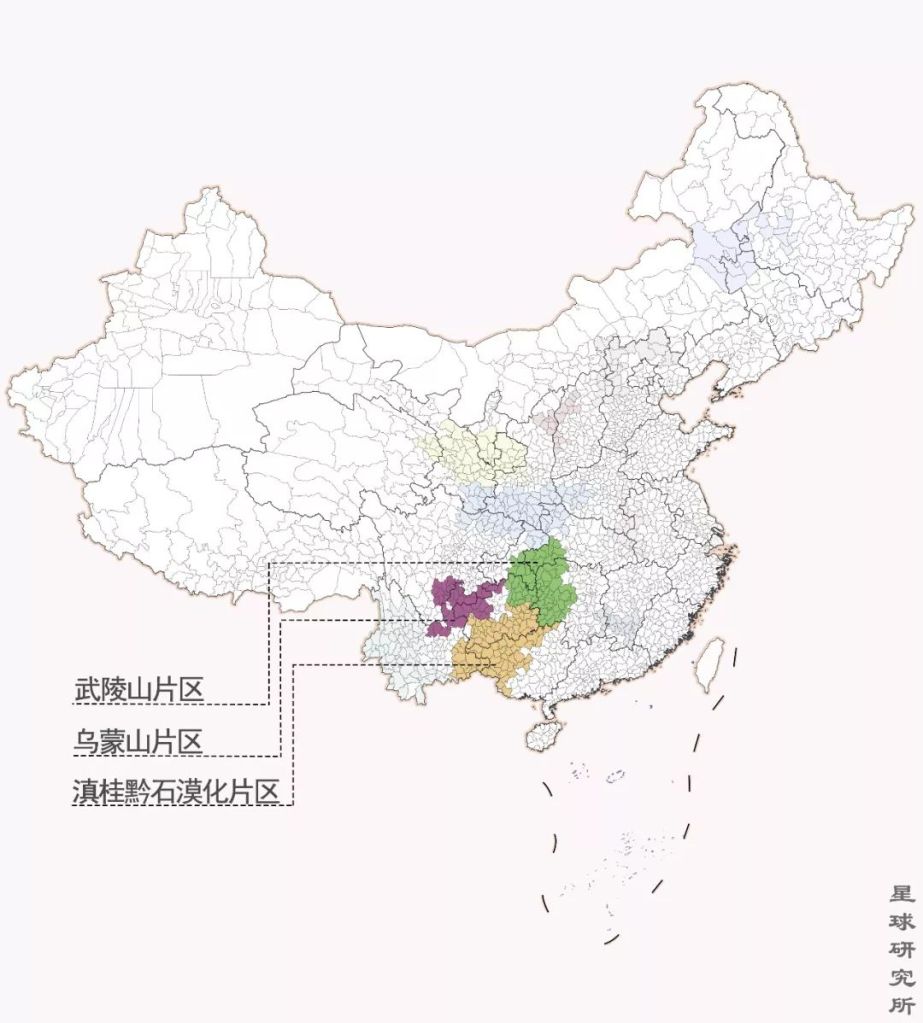

Looking at the map of China, you will find 11 concentrated contiguous destitute zones that account for almost 15% of the country’s total land area. They also represent the most poverty-stricken 15% of the entire Chinese population.

By late 2017, about 30.46 million people were still living in extreme poverty in this 15% of China.

Southern Ranges of Greater Khingan Zone (大兴安岭南麓片区), Yan Mountain-Taixing Mountain Zone (燕山–太行山片区), Lüliang Mountains Zone (吕梁山片区), Liupan Mountains Zone (六盘山片区), Qinba Mountains Zone (秦巴山片区), Dabie Mountains Zone (大别山片区), Wuling Mountains Zone (武陵山片区), Wumeng Mountains Zone (乌蒙山片区), West Yunnan Border Zone (滇西边境片区), Yunnan, Guangxi and Guizhou Rocky Desertification Zone (滇桂黔石漠化片区). Luoxiao Mountains Zone (罗霄山片区)

This map excluded regions that have already initiated special policies, namely Tibet, the four prefectures in southern Xinjiang, and Tibetan-populated regions in Gansu, Qinghai, Sichuan and Yunnan; together, these 14 regions would account for an even larger area in the country

(diagram: 刘昊冰, Institute for Planets; adapted from 丁建军《中国11个集中连片特困区贫困程度比较研究》)

They have been excluded from the country’s astonishing economic development, and have never crossed path with prosperity or modernisation, not even a well-off life.

After four decades of reform and opening up in China, why is there wide-spread poverty still? Are people in these regions especially lazy? Or are they not bright and innovative enough to thrive in modern times?

Neither.

Instead, geography and environment are always the final stronghold of extreme poverty in China. The enchanting landscapes that amaze countless foreign travellers are exactly what make life impossibly difficult for the local people.

1. Karst-associated poverty

One of the most classic types of poverty can be referred to as karst-associated poverty.

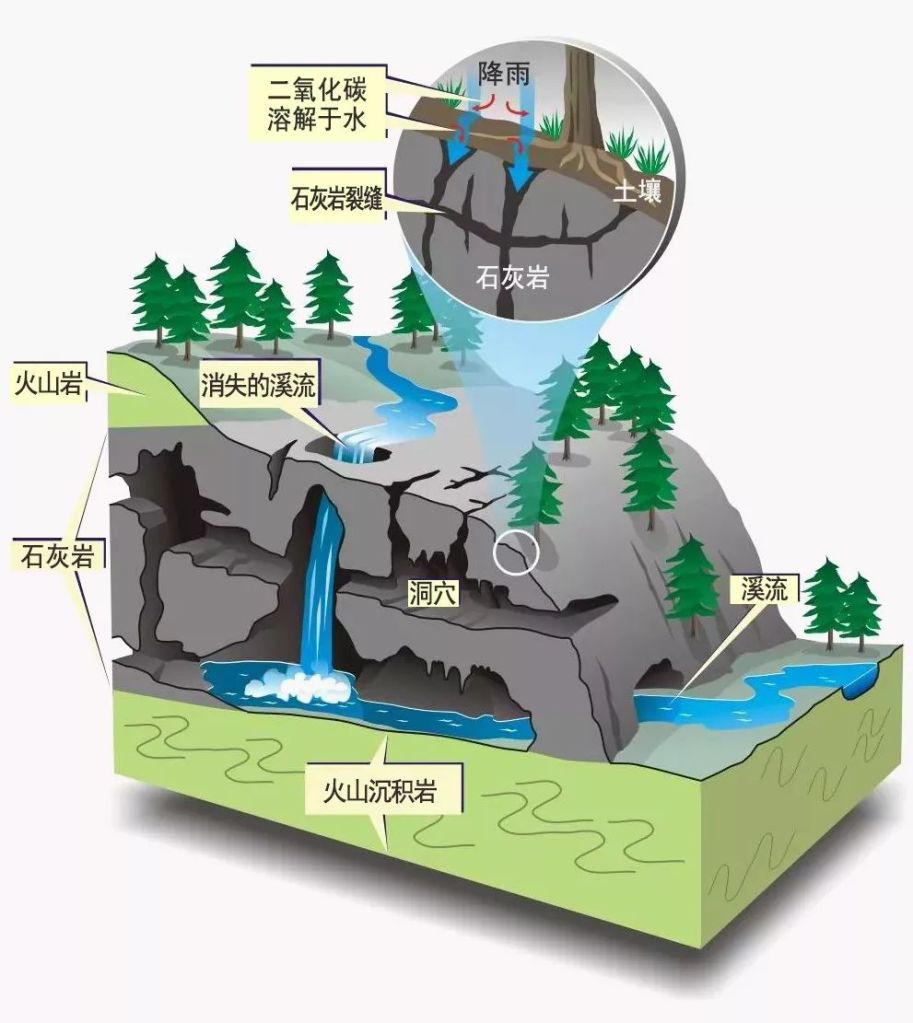

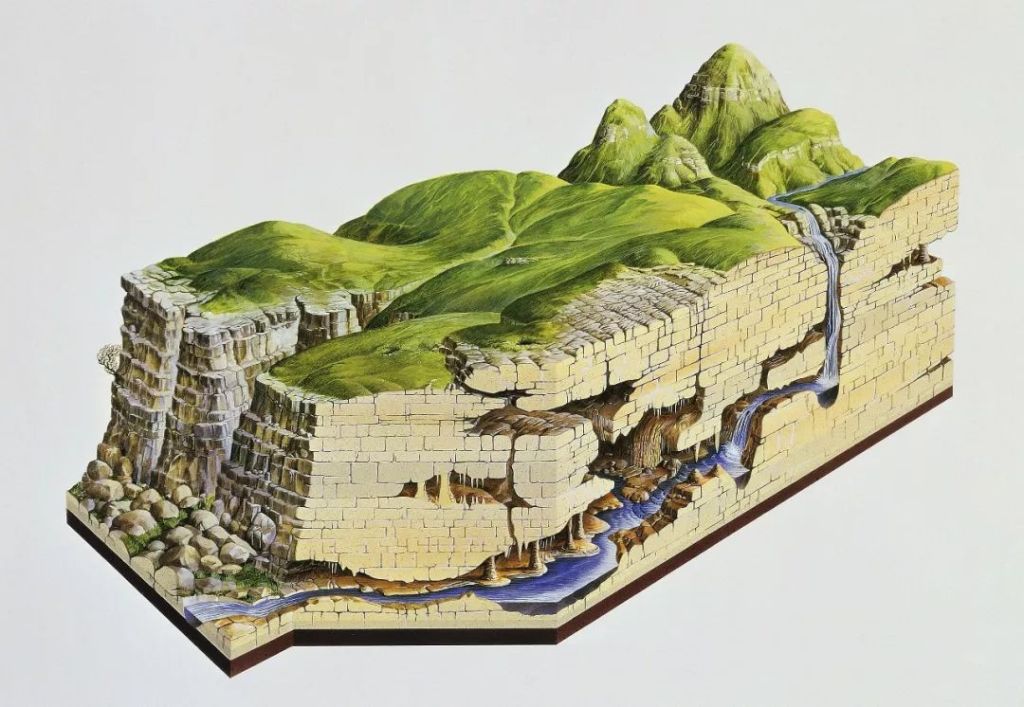

Back in the late 19th century, geographers in the west were studying dissolvable rocks on the Karst Plateau in southern Europe. They found that in these regions, the erosion of bedrocks by water forms a spectrum of unique landforms, including sinkholes and caves, which they then collectively named karst landforms.

Soil (土壤), limestone (石灰岩), volcanic rock (火山岩), sinking stream (消失的溪流), cave ( 洞穴), volcanic sedimentary rock (火山沉积岩)

(diagram: Vancouver Island University)

Decades later, Chinese geographers realised that the karst landforms on the Karst Plateau are just the tip of an iceberg. They are actually much more common back at home in China.

In southern provinces, including Yunnan, Guangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan and Hunan, soluble rocks in these karst landforms have a total sediment thickness of 10 kilometres and an exposed area of more than 500,000 square kilometres. Abundant rainfall in southern China leads to persistent erosion in these rocks, wearing them out with every drop of water and remodelling the landscape over the past hundreds of millions of years.

Carbonate rocks are the most common soluble rocks; the red dotted line encircles dense areas of karst landforms

(diagram: 刘昊冰, Institute for Planets; reference: 《中国自然地理图集》)

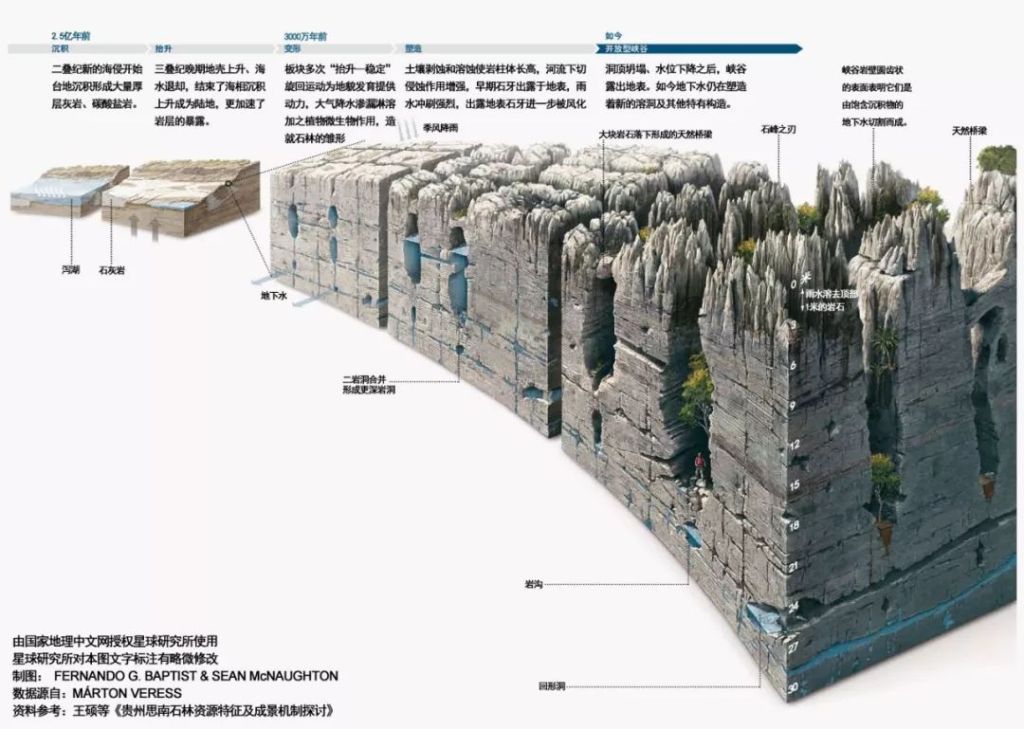

Streams of water flow across the rocky surface of the land and carve out networks of grooves that dig deeper and deeper. Rock pillars form in between and become increasingly spiky and lofty over time, eventually reaching up to 30-40 metres high. Each of these pillars has a unique appearance, sometimes like a sword or a tower, and sometimes a fat column or even a mushroom. Clustered together like a thick plantation of stones, these structures are known as stone forests.

(diagram: adopted from National Geographic with permission)

One of the them is the Sinan Stone Forest in the Wuling Mountains Zone in Guizhou. Thousands of stone pillars span an area of 4.9 square kilometres, where they tango with flourishing woods.

(photo: 全景)

In the Guzhang Red Stone Forest in Xiangxi, flowing water left clear marks all over the fuchsia carbonate stones.

(photo: 图虫创意)

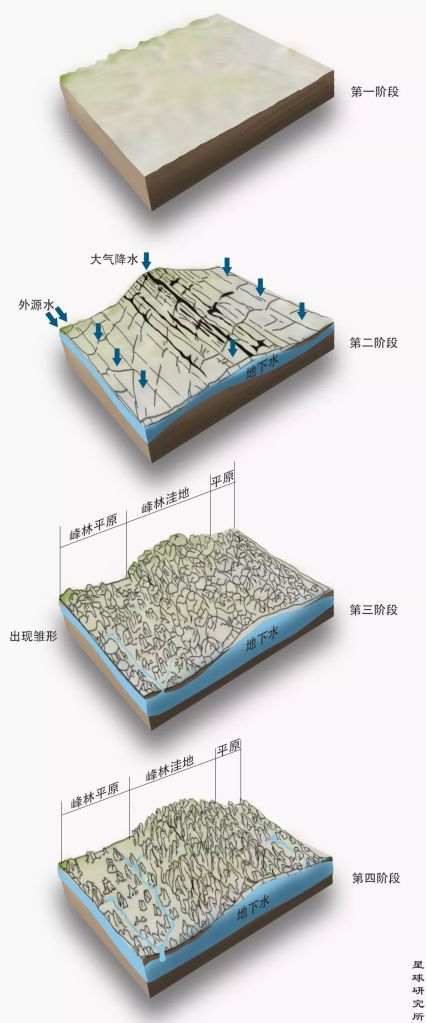

There is another type of erosion that occurs at a much grander scale than stone forests. In vast regions with a thick bed of soluble rocks, water carves out ranges of rolling hills. Hills that have a connected base are called peak-cluster karst, while those that are more dispersed with relatively separated bodies are peak-forest karst.

(diagram: 刘昊冰, Institute for Planets; reference: 朱学稳《桂林岩溶地貌与洞穴研究》)

A classic example of peak-cluster karst is the Qibainong in Dahua County, Guangxi, which is designated to the Yunnan, Guangxi and Guizhou Rocky Desertification Zone. The skyline of Qibainong is sketched by a sea of more than 9000 rocky hills, each with an elevation of 800 metres or above. It is the largest and the most dense peak-cluster karst landform in the world.

(photo: 钟永君)

Luoping County in Yunnan, also belonging to this desertification zone, has a typical peak-forest karst landform. The numerous hills here are round and mellow like little steamed buns.

(photo: VCG)

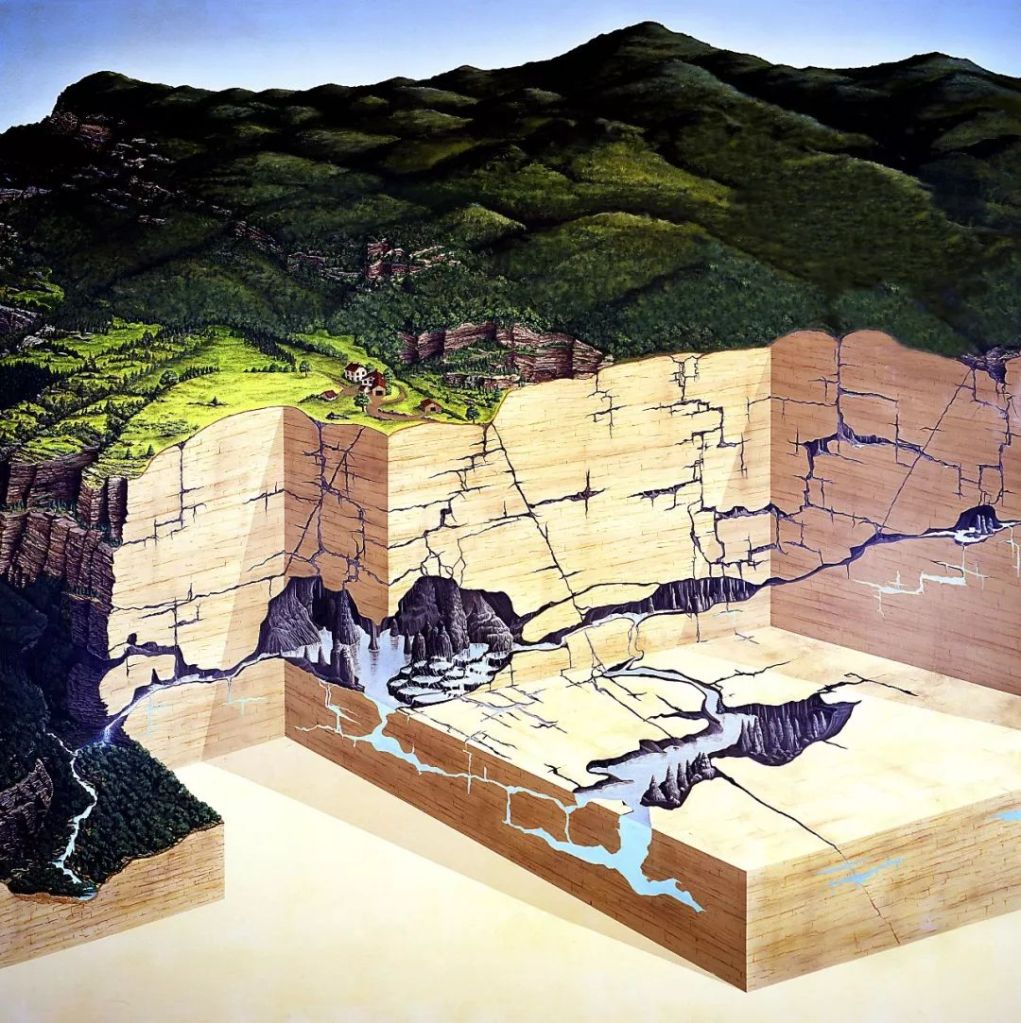

Erosion beneath the ground also plays a big role in shaping the landscape. It produces enormous karst caves.

(diagram: VCG)

The Shuanghe Cave in Guizhou is 117 metres long. It is the longest karst cave in China.

(photo: 赵揭宇)

One can find in these karst caves majestic cave chambers, which can have a ceiling height of 200 metres or more, and a floor area of 116 square metres, which is equivalent to 16 football pitches pieced together.

It is the largest karst cave chamber in China

(photo: 向航)

As erosion continues, cave chambers eventually collapse and create massive sinkholes (or tiankeng in Chinese, literally meaning ‘heavenly pit’).

These are in the Wumeng Mountains Zone

(photo: 柴峻峰)

The cliff walls of these sinkholes are almost vertical, and their width and depth easily exceed 100 metres.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

The largest sinkholes can be more than 500 metres wide and deep. In fact, the 3 largest sinkholes in the world are all located in China within the 11 destitute zones, namely the Xiaozhai Tiankeng in Fengjie County, Chongqing, the Dashiwei Tiankeng in Leye County and the Haolong Tiankeng in Bama Yao Autonomous County, Guangxi.

(photo: 全景)

The variety of sceneries in these regions are absolutely stunning and unique, that many outsiders think the local people must be enjoying an enviably peaceful and leisure countryside lifestyle.

Sceneries here are definitely a match for the famous Guilin landscapes

(photo: 谭嗣怀)

This popular impression, unfortunately, cannot be further from the truth. These sceneries are actually the very reason for extreme poverty. Three of the 11 destitute zones, the Wuling Mountains Zone, Wumeng Mountains Zone and Yunnan, Guangxi and Guizhou Rocky Desertification Zone, are severely struck by water and land shortage.

(diagram: 刘昊冰)

First, the real problem lies in the absolute lack of water storage capability of the land surface. Rainfall in these three regions are often above 1000 millimetres, which is almost twice as much as in Beijing, but numerous sinkholes of all sizes constantly ‘suck’ up the water like a bottomless void.

(diagram: VCG)

Rainwater and groundwater join forces underground to form the largest subterranean river system in China, which is comprised of 2836 rivers that stretch 13,000 kilometres in total.

The river emerges out of nowhere forming a waterfall down a voluble cave mouth

(photo: 李贵云)

The land surface, on the contrary, suffers from frequent droughts.

(photo: 李贵云)

This forces the locals to rush about for water all the time.

(photo: 李贵云)

Second, the constant water flow washes away all the deposits on the land surface, leaving behind little or no topsoil, which usually requires at least 100 years to replenish by a mere centimetre. Lacking soil, the locals have to be creative to locate sparse and dispersed spots that are suitable for crops.

These are located in the Wuling Mountains Zone

(photo: 柳勇)

And squeeze their fields in the cracks of the karst landforms.

These can be among stone forests.

(photo: 李贵云)

Or surrounded by peak-clusters.

It is also called the tornado field for its unique spiral appearance

(photo: 焖烧驴蹄)

In these lands, water resource is limited and fertile fields are scarce. What they have in abundance are just bare rocks scattered all over the place, and hence are referred to as rocky deserts.

(photo: 李贵云)

The rocky desertification in Wuling Mountains, Wumeng Mountains and Yunnan, Guangxi and Guizhou Rocky Desertification Zones have led these regions into the most precarious poverty in China, which are faring even worse than those on the notorious Loess Plateau.

There are more than 100 of such national-level poverty-stricken counties. For generations, several dozens of ethnic minority groups have inhabited these barren lands, and have suffered from relatively backward productivity and literacy rate.

Despite the constant drop-out of a number of counties, there are still more than 100 poverty-stricken counties as of 2018

(photo: 张源)

The primary school in a cave that once shocked the whole country was also located in these regions.

The school has now been relocated

(photo: 李贵云)

Children have to trek through the unforgiving stone forests every day on their way to and back from school.

They are students from the Pangzhai Primary School in Ynagmei Village, Liupanshui, Guizhou

(photo: 李珩)

Even schools that are better equipped can hardly find enough space for a playground.

The school is leaning against a mountain cliff with a waterfall hanging above

(photo: 李珩)

This is what we call karst-associated poverty.

(original photo: Google Earth)

2. Mountain-gorge-associated poverty

Another prevailing type of poverty can be labelled as mountain-gorge-associated poverty.

The terrains of China are divided into a three-step ladder from west to east, and between each step there is a massive elevation difference.

The first (第一级阶梯), second (第二级阶梯) and third step of the ladder terrain (第三级阶梯)

(diagram: 刘昊冰, Institute for Planets)

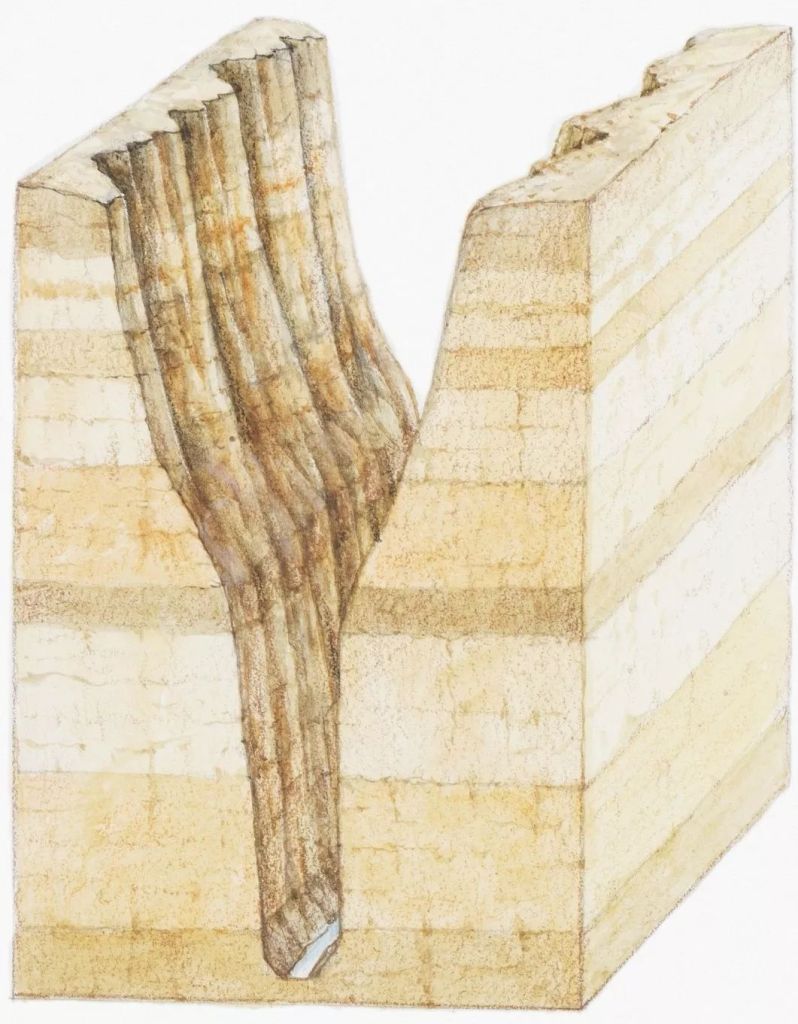

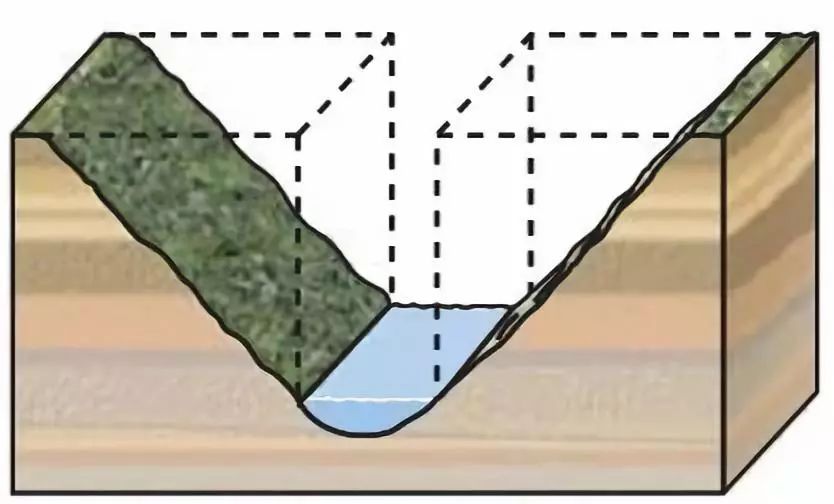

Rivers that originate in the Tibetan Plateau pour down the ladder terrain and cut through mountains throughout their journey, carving out magnificent V-shaped valleys known as gorges. During the early phases of erosion, slopes of these V-shaped gorges are often almost vertical.

(diagram: VCG)

The Maling River, which rises at the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, has sculpted continuous ranges of gullies as it traverses Guizhou, where more than 60 waterfalls rush down the precipitous cliffs and stir up roaring waves in the coursing stream deep down.

(photo: VCG)

As gorges widen and deepen with persistent erosion, they become the typical canyons.

These are very common in the Hengduan Mountain Range at the rim of the Tibetan Plateau, where Gaoligong Mountain, Nu Mountain, Shaluli Mountain and Daxue Mountain line up in tandem, with rivers including the Nu River, Lancang River and Jinsha River running through. The soaring mountain ranges and deep valleys make a phenomenal contrast.

(photo: 李珩)

Adding on top are the rift valleys and ground seams created by tectonic activities.

China is truly the kingdom of mountains and gorges.

(photo: 杨勇)

On one hand, mountains and gorges have been instrumental in sustaining a rich mountain biodiversity. They are regarded as the Chinese plant and animal kingdom which hold a comprehensive gene bank.

(photo: 商睿)

On the other, they bring along mountain-gorge-associated poverty to the 11 destitute zones.

Villages are often sitting right next to raging torrents on the edge of a cliff.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

Where slopes are even steeper, it seems like the whole village could fall off the cliff any time.

(photo: 杨涛)

Locals utilise the last block of relatively gentle slopes to build terraces.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

Towering mountains block humid air from entering the canyons in between and form rain shadows. As dry and warm foehn confiscates the last scent of vapour, canyons are baked into dry-hot river valleys where nothing grows.

(photo: 商睿)

But these problems are still relatively minor if we compare it with the complete blockade of transport and commute. Canyons are often miles deep with a raging river at the bottom. People can only travel carefully along the unfenced cliff side.

(photo: 杨涛)

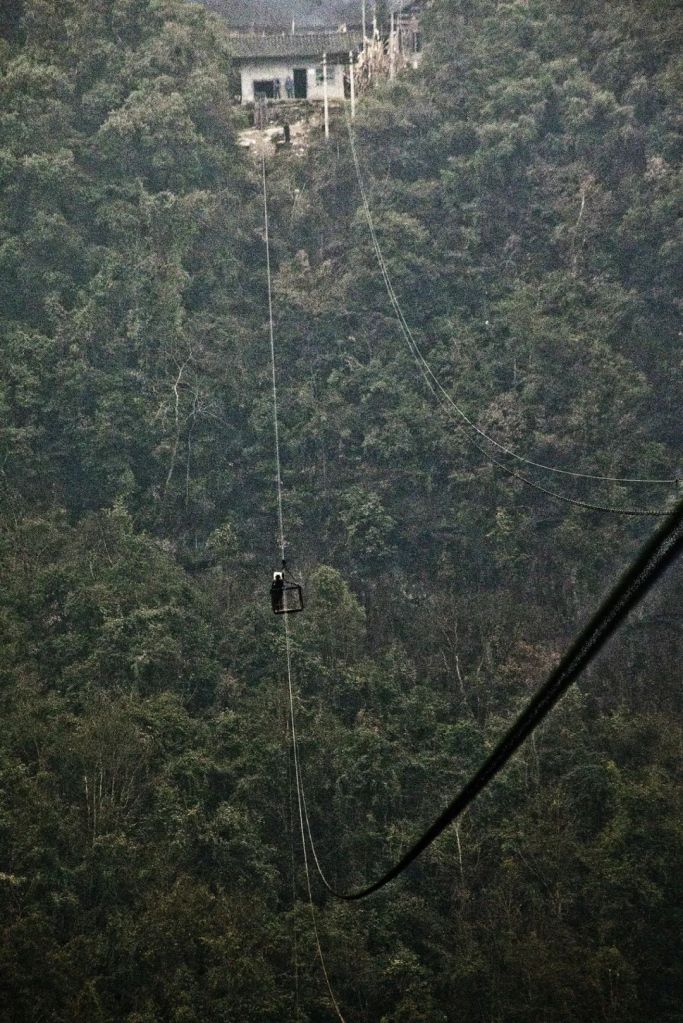

Or bravely jump onto a zip wire for a thrilling journey.

(photo: 芮京)

Other travellers might prefer the more advanced cableways, which is ever so slightly more reliable with a metal carrier.

(photo: 张源)

Even with the completion of many modern bridges, some zip wires and cableways are still in use* and remain as part of the chilling landscape of China’s mountain ranges.

*Translator’s comment: most, if not all, zip wires and cableways have been replaced by modern bridges as of 2020

(photo: 钟永君)

Isolation of the locals from the rest of the world results in societal and technological underdevelopment in their communities, some of which are still living on slash-and-burn cultivation methods. For instance, the disposable income per capita for villagers in Ximeng Va Autonomous County in Pu’er, Yunnan, was only about 70% of the nation’s average in 2017.

The Va people transitioned directly from a primitive society to a modern society in the 1950s, and have since resided in new villages centrally established by the government

(photo: 张源)

When our photographer arrived in a Va village in Ximeng Va Autonomous County, he was welcomed with a great feast of yam by local villagers.

(photo: 张源)

(photo: 张源)

Life is still striving in the most remote crevices among the grand mountains and gorges.

(photo: 商睿)

3. Other causes of poverty

In addition to karst, and mountains and gorges, there are still many different factors leading to poverty in this 15% of land. People in these regions are also facing soil desertification and aeolian processes.

(photo: 刘忠文)

Enduring droughts.

(photo: 刘广辉)

And suffering from serious water pollution.

(photo: 李杰)

They are crossing rivers on falling bridges.

This bridge was the only way out of the village for the locals in Baiyu Monastary Village, they have no choice but to risk their lives because there are no alternative routes.

(photo: 李杰)

Mountaineering their way to school every day.

(photo: 杨勇)

And experiencing long and painful separations from family.

This is a large village with about 2000 residents; since most younger people are working in larger cities or other provinces, there are many left-behind children waiting at home

(photo: 卢文)

But they are still smiling.

(photo: 李杰)

And courageously looking forward to their future.

(photo: 李杰, taken in 2010)

China is aiming to eliminate poverty by the end of this year (2020). Apart from building the much needed infrastructure, we should not forget about education in these destitute zones and the mental development of local children.

The Longshan County in Wuling Mountain Zone is a national-level poverty-stricken county full of karst landforms. Hundreds of mountains roll across every inch of land in sight.

Located at the foot of one of these mountains in Qianwei Village is the Guangen Primary School, one of the target primary schools of the Mutian Book Donation (幕天捐书) charity project.

For children in remote villages, learning should not be restricted to memorising textbooks, but ought to also involve stimulating extracurricular reading.

Mutian Book Donation has set up reading corners in these schools in hope to expose children to new and lively knowledge and boost interests in learning, which will ultimately broaden their horizon and better prepare them for the world outside.

With the vision of ‘every child deserves the opportunity to thrive‘, the Mutian Book Donation charity project aims to cultivate reading habits among village children, which is achieved through promoting book donation in the general public.

As of early July 2018, the project has reached 29 provincial-level administrative regions, and has set up 7362 reading corners in 836 village schools, enlightening 264,566 children with 1,353,883 donated books.

Donating a book and passing on hope is what everyone can do to help realise the charity project’s vision.

It is also our most sincere wish that with a better educated next generation, we can eliminate poverty while preserving all the enchanting landscapes of our motherland.

Reference

各片区《区域发展与扶贫攻坚规划 (2011-2020 年)》

郭来喜/ 姜德华《中国贫困地区环境类型研究》

丁建军《中国11个集中连片特困区贫困程度比较研究》

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光