Original piece: 《中国的湖泊,有多美?》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 风子

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

For better visual effects, most photos included in this piece were taken in landscape mode.

Lakes are often romanticised as pearls.

There are 24880 of such pearls across the land of China.

They differ greatly in size, where 2693 of them have a surface area larger than 1 square kilometre. When combined, they cover a total area of 81414.56 square kilometres.*

No two pearls look the same.

Some are long and narrow, others are curved or round or with sharp edges. The variety of their appearance is beyond imagination.

* These data are based on《我国的湖泊》(Lakes in China) by 王洪道 et al. and 《中国湖泊调查报告》(Survey on China’s Lakes) by Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences; data variation may exist for lake count and area owing to differences in methodology and time of data collection

The 51st lake and those after are represented by dots which do not reflect their actual shapes

The 10 biggest lakes: Qinghai Lake (青海湖), Poyang Lake (鄱阳湖), Dongting Lake (洞庭湖), Lake Tai (太湖), Hulun Lake (呼伦湖), Siling Tso (色林错), Namu Tso (纳木错), Hongze Lake (洪泽湖), Xingkai Lake or Lake Khanka (兴凯湖), Bosten Lake (博斯腾湖)

Reference: Report on Lake Survey in China by Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences

(diagram: 赵榜 & 陈思琦, Institute for Planets)

Distributed all over the country, they can be found on top of mountains.

(photo: 张文静)

Or on the plains.

From inlands.

To the shore.

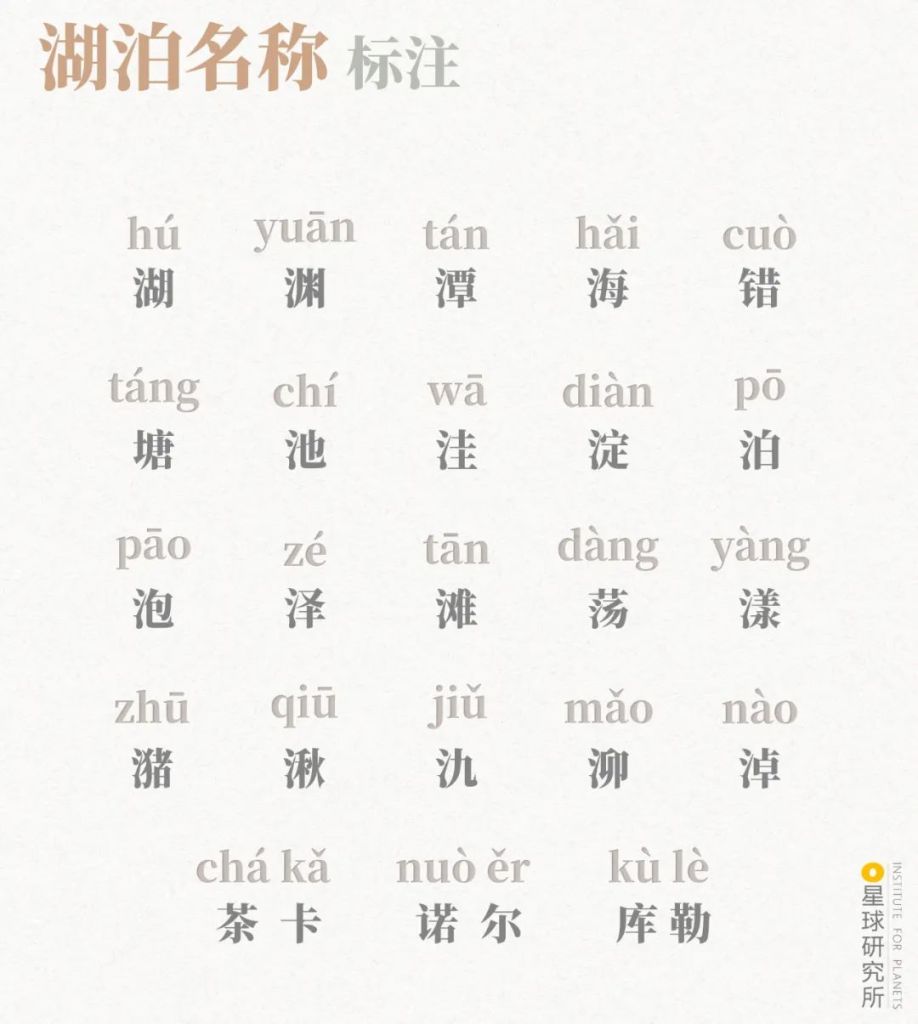

They have a library of names because of different dialects and customs.

So where do all these lakes come from?

How have they sculpted the landscape and adorned the nature?

To answer these questions, we first need to learn about the two prerequisites for lake formation: the lake basin, a natural depression in the land surface, and the water body that resides within. A lake basin determines the shape and size of the water body. Without it, lakes do not even exist.

In China, there are 8 natural forces responsible for carving all kinds of lake basins. Understanding them will help us answer the questions above.

1. Volcanism 火山的力量

Let us start with the ‘pyro’ force of fiery volcano eruptions.

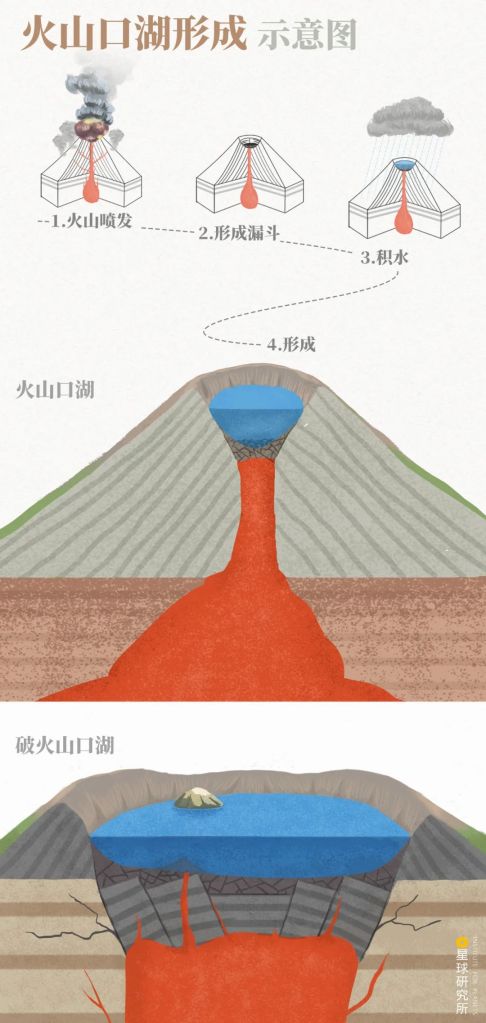

Below the crust, fervent magma undergoes vigorous movements, constantly looking for a weak point in the rocks above. When such crack is spotted, the magma is blasted out. Together with the ash and tephra ejected from the volcano, the lava cools down and piles up around the vent to form a volcanic cone.

When the volcano becomes dormant, the cooling magma column shrinks and causes the apex of the volcanic cone to collapse inwards to form a sinkhole with the shape of a bowl-like funnel. As rain water accumulates in the sinkhole, a volcanic crater lake gradually takes form.

Multiple eruptions may cause fault settlement in the volcanic cone, resulting in caldera lakes (破火山口湖)

(photo: 赵榜, Institute for Planets)

Like a sacred torch lifted high up in the sky, these lakes are often praised as tianchi (literally ‘lake of the heavens’).

There are clusters of volcanic crater lakes in the northeast regions of China. The Arxan Heavenly Lake and Heavenly Lake of the Moon near Arxan, Greater Khingan, are the classic examples.

Viewing from above, the almost perfectly round Heavenly Lake of the Moon could well be mistaken for an enchanting sapphire embedded in the forest.

After numerous eruptions which caused continuous crater expansion, the well-known Heavenly Lake of Changbai Mountain (literally ‘Perpetually White Mountain’) is currently the largest volcanic crater lake in China.

It is also the deepest lake in China with an average depth of 204 metres and 373 metres at the deepest. Having a water volume of 2 million cubic metres, the Heavenly Lake is much larger than many large lakes on the plains.

The total area of the lake is 9.82 square kilometres

(photo: 翟东润)

2. Glacial movement 冰川的力量

The grim force of ‘ice’, on the contrary, carves and reshapes mountains in a different but equally drastic manner.

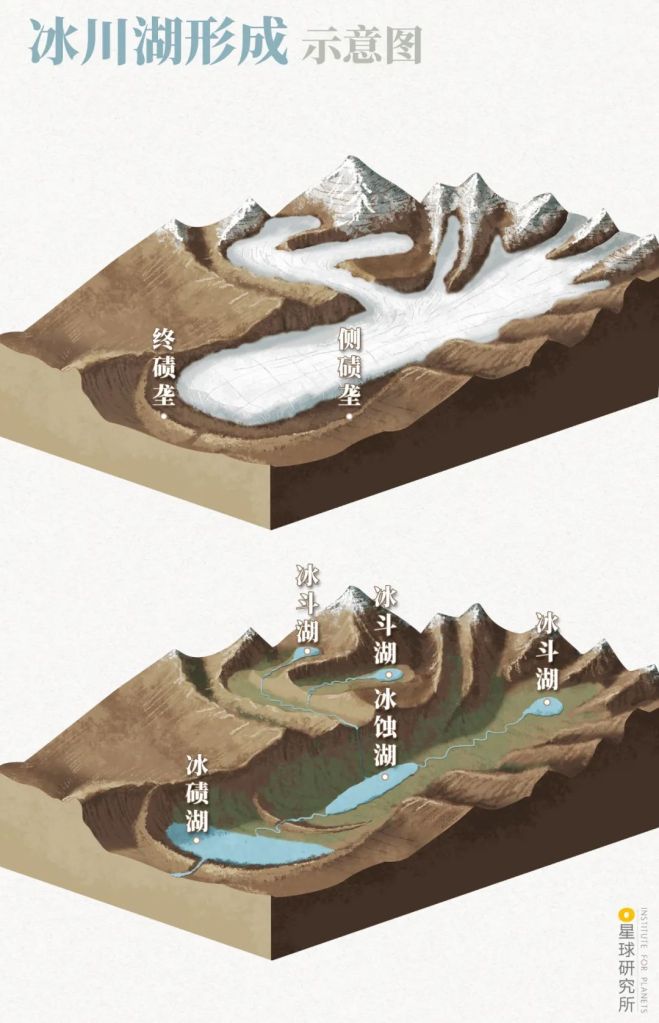

During the ice age, glaciers on the western mountains in China were much thicker than today. As temperature rose, they melted and retreated. This leaves behind many depressions formed from glacial erosion or glacial troughs rimmed with moraines which become all kinds of glacial lakes today.

Lateral (侧冰碛) and end moraines (终冰碛) formed from glacial movement

Examples of glacial lakes include glacial erosion lakes (冰蚀湖), moraine-dammed lakes (冰碛湖) and cirque lakes (冰斗湖)

(diagram: 郑伯容, Institute for Planets)

They are mostly distributed at high attitudes with relatively small basins. Frequently supplemented by meltwater, they are the source of many rivers flowing along mountain ranges.

Repeated retreats and advances of glaciers result in a series of connected glacial lakes, like a string of pearls implanted into the glacial troughs.

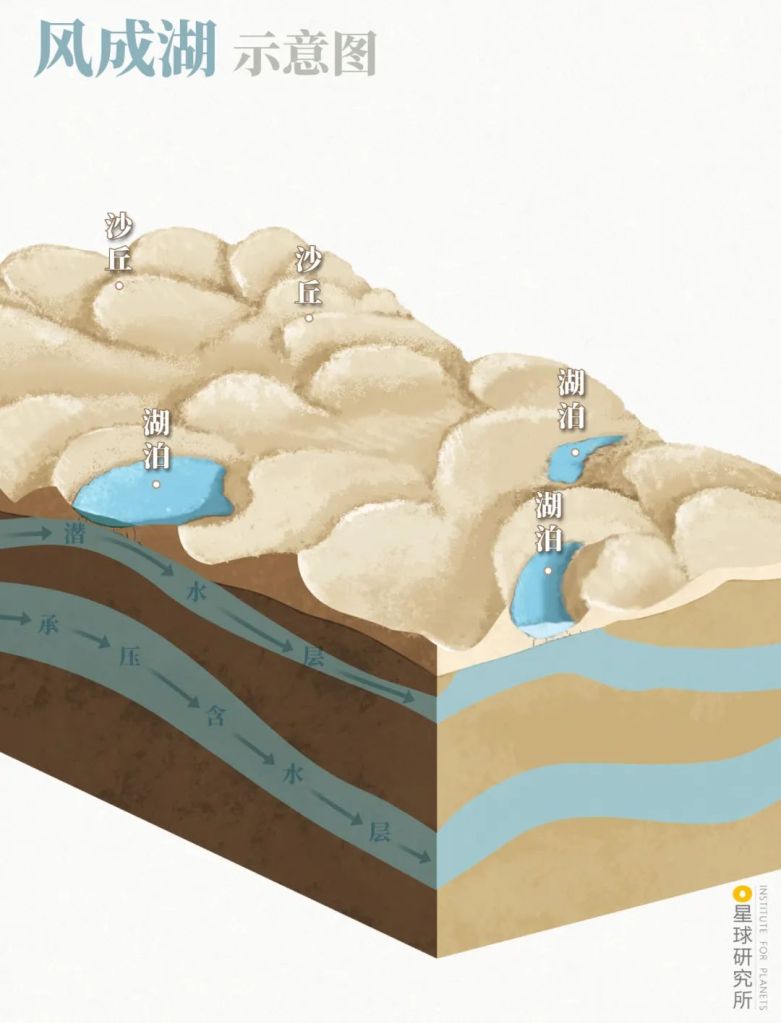

3. Aeolian processes 风的力量

For arid regions like deserts, the predominant creator of lakes is none other than the force of the ‘wind’.

Wind sweeps across dry lands, agitating and flinging clouds of sand and dust.

Over time, wind creates rippled surfaces with crests and troughs known as sand dunes. Supplemented with groundwater and rain, the depressions among the dunes turn into aeolian lakes.

Structures: sand dune (沙丘), lake (湖泊), water table (潜水层), confined aquifer (承压含水层)

(diagram: 郑伯容, Institute for Planets)

Aeolian lakes are abundant in the northwest desert regions, mainly scattered across Taklamakan Desert and Badain Jaran Desert.

As well as Tengger Desert and Kumukuli Desert.

(photo: 李学亮)

Some of these lakes nurture vegetation or microbial lives. Others evaporate under the blazing sun leaving behind colourful layers of mineral salt.

Either way, these lakes smear delightful streaks of vivid paint on the dull desert.

4. Oceanic processes 海洋的力量

The ocean is an active player in formation of lakes along the coast.

When a deposition bar or a spit created by the sea current becomes big enough and closes the re-entry of the shore, it separates a shallow body of water from the sea and forms a lagoon.

Sand (泥沙) drifting with the current (沿海漂流) gradually closes up the bay (海湾) forming a spit (沙嘴) that encircles a lagoon.

(diagram: 赵榜, Institute for Planets)

Owing to the differential impact of coastal waves and tidal force, lagoons in China are rarely found along the coast of East China Sea, but mainly concentrated in other coastal provinces including Liaoning, Hebei, Shandong, Guangdong and Guangxi.

There are many of them along the coast of Hainan and Taiwan.

They are often used as sheltered ports or crop fields.

5. Karstification 岩溶的力量

In regions rich in soluble carbonate rocks, flowing water continuously erodes the land and forms depressions, sinkholes and caves. When the drainage is blocked by a collapsed surface or deposition of insoluble substance, water accumulates and a karst lake is formed.

Karst terrains are widely distributed in southwest regions of China, and so are karst lakes.

Formation of karst lakes are usually spontaneous, as exemplified by the Caohai Lake (literally ‘sea of grass’) on the Weining Mountain in Guizhou.

The heavy rain that persisted from July to August in 1857 rushed down plenty of soil and organic sediments which blocked the sinkhole of an ancient lake basin. This gave birth to the biggest lake in Guizhou.

On the west coast of Lake Napa in Shangri-La, Yunan, there are three sinkholes with enlarging cracks in the lake basin. During flood periods, drainage of the water body through these cracks often create whirlpools. In the dry season, this lake becomes a shallow wetland.

6. Mass wasting 堰塞的力量

Compared to karst lakes, the formation of landslide dams (also known as debris dam, barrier lake or quake lake) is even more abrupt and drastic.

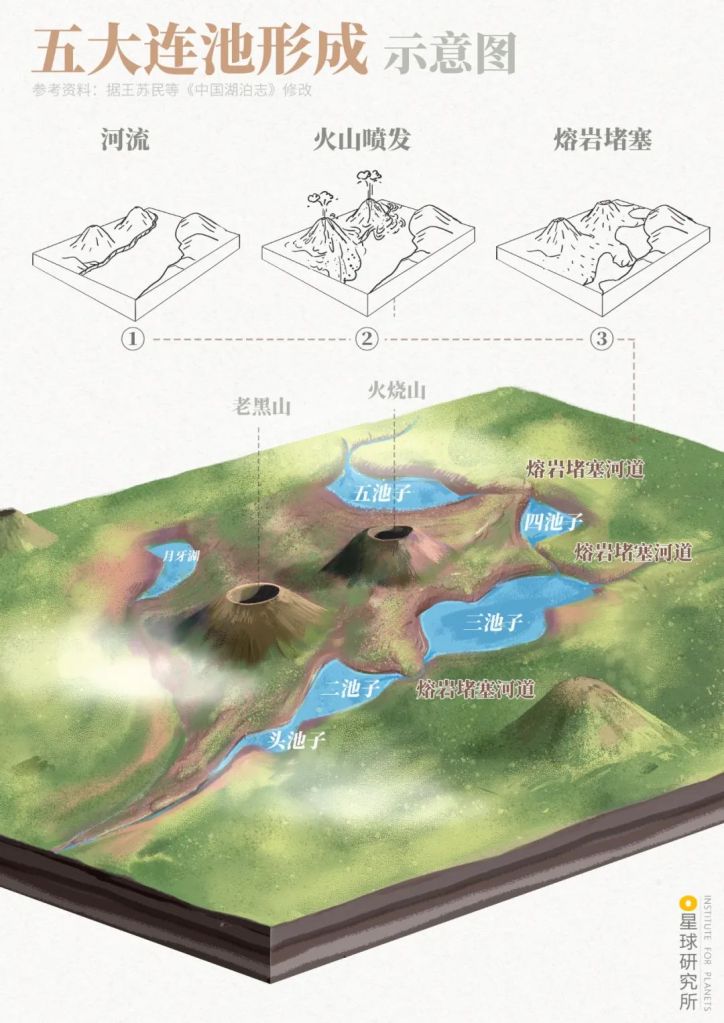

Between 1719 to 1721, two volcanoes named Laohei and Huoshao erupted together in Dedu County, Heilongjiang. Large amount of lava was ejected and poured into the Bailong River. Dammed by the lava, the disturbed river basin became a series of connected lakes like a string of mala beads.

This world-famous lava-dammed lake is called the Wudalianchi (literally ‘five connected pools’).

It is formed from a river (河流) which experienced lava damming (熔岩堵塞) after volcano eruptions (火山喷发)

Volcanos: Laihei (老黑山), Huoshao (火烧山)

Lakes: Head pool (头池子), Second pool (二池子), Third pool (三池子), Fourth pool (四池子), Fifth pool (五池子), crescent pool (月牙湖)

(diagram: 赵榜, Institute for Planets)

Also located in Heilongjiang is the Jingpo Lake, which was created when basalt formed from cooled lava blocked the Mudan River and its tributary.

It is the largest lava-dammed lake in China.

Lake water flows steady over the basalt dam and down a waterfall, forming a deep basin by the banks

(photo: VCG)

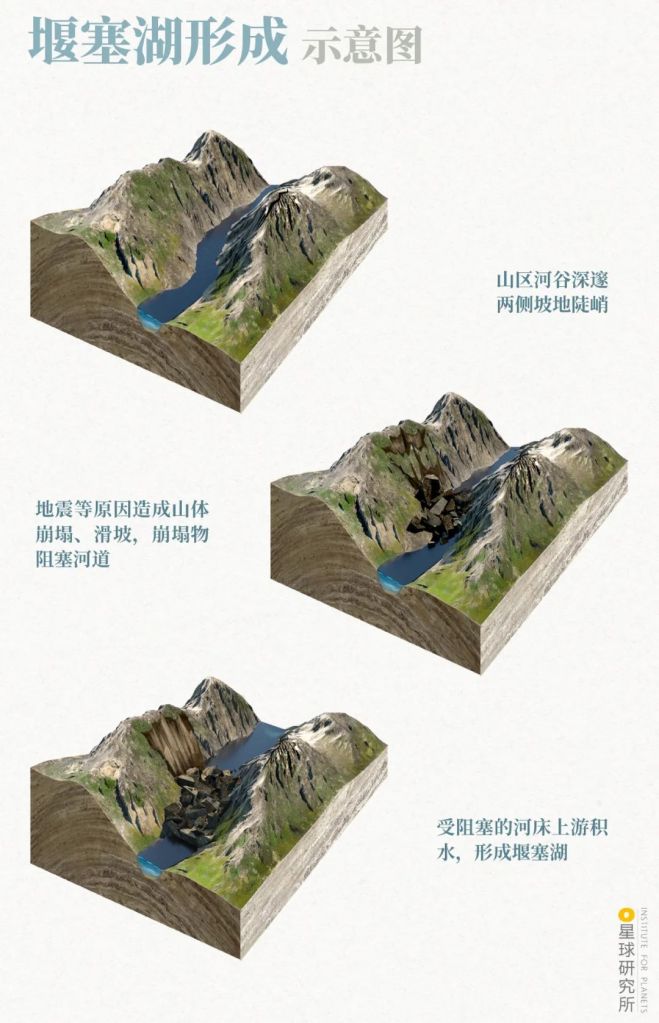

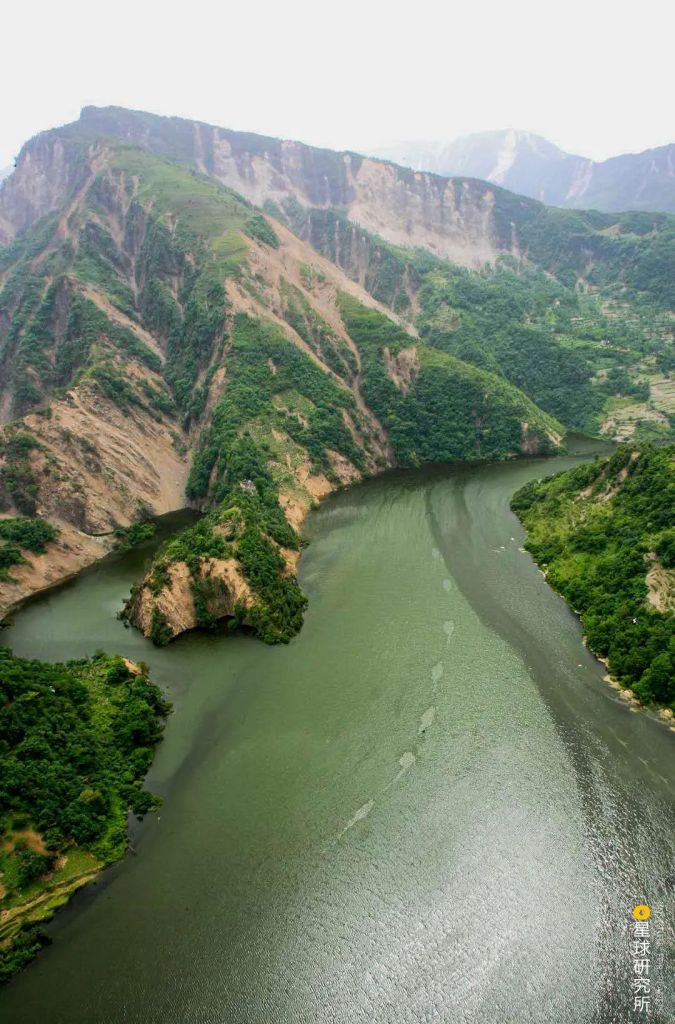

Landslide dams are more commonly created through slumping.

Landslides and mudslides are frequent in the mountainous regions of western China due to earthquakes, glacial movements and heavy rainfall. Slumps block the river channel and form lakes on the upstream.

1. Rivers flow through precipitous cliffs along the mountains

2. Mass wasting such as earthquakes leads to landslides which blocks the river channel

3. Water accumulates on the upstream forming a landslide dam

(diagram: Institute for Planets)

In 1933, Diexi in Mao County, Sichuan, was struck hard by a 7.5-magnitude earthquake. The subsequent massive landslide led to large amount of land mass collapsing into the Min River.

This resulted in multiple landslide dams now known as the Diexi Lakes. The ancient town of Diexi was forever buried with the collapsed land mass.

Glacial movements near Guxiang Village in Bomê County, Tibet, triggered a mudslide in 1953. Blocking the Parlung Tsangpo River, the mudslide indirectly created the Guxiang Lake, which is 5 kilometres long and 1-2 kilometres wide with a depth of 20 metres.

Unlike other lake types, the dams of landslide lakes are inherently loose, which can fail catastrophically and lead to serious floods and loss of lives in the downstream.

Shortly after the Sichuan earthquake on 12 May 2008, the dam of Tangjiashan Lake, created by the earthquake on the upstream of Beichuan County, was on the verge of failure due to potential overtopping. This forced the earthquake relief squad to relieve the pressure in the lake by building spillways through manual digging and using airdrop mining machinery, while simultaneously evacuating thousands of citizens.

Well, landslide dams are not always ‘all but good’.

When cultivated over an extended period, they spill out picturesque landscapes.

The many exquisite lakes in Jiuzhaigou, including Chang Lake, Fangcao Lake, Swan Lake, Jianzhu Lake and Panda Lake, are all perfect examples of captivating sceneries moulded by the force of mass wasting. The Wuhua Lake (literally ‘five flower lake’), most gorgeous of all Jiuzhaigou lakes, has all the classic features of a landslide dam.

We have now come across six natural forces that created thousands of lakes with all kinds of features.

But the vast majority of the lakes they create are all too tiny, most of which with surface areas smaller than 1 square kilometre and hence are usually neglected.

Large and medium-sized lakes with more familiar names, on the other hand, are created by the remaining two forces.

7. Fluvial processes 河流的力量

In plain regions that are nourished by plenty of fresh water, lakes are primarily created by rivers.

The sediments carried in rivers may form depressed basins through uneven deposition, or gradually build up a sand bar that holds the river water behind still. Rivers can also invade the adjacent lowlands during floods, or abandon minor channels that eventually stock up sufficient water to become a lake.

These lakes are collectively referred to as fluvial lakes.

Because of these effects, the East China plains along the midstream and downstream of Yangtze River and Huai River harbour a large number of lake clusters.

The Jianghan Plain, for instance, still retains 181 lakes with areas larger than 1 square kilometre, including the Hong Lake, Liangzi Lake and Futou Lake, despite the rapid drop in the number of existing lakes in the region.

Since 1194, the Yellow River had changed its course occasionally. It engulfed the Si River and ran into the the Huai River. The heavy silting in both Si River and Huai River led to significant water retention that ultimately created a series of lakes, making it a classic case study for fluvial lake formation.

The lakes that arose from poor drainage along the Si River, namely the Nanyang Lake, Dushan Lake, Zhaoyang Lake and Weishan Lake, were further expanded by human activities including canal construction and became the widely known Nansi Lake.

Water retention was most severe at the confluence of the Si River and the mainstream Huai River. After the dam construction in the downstream, many smaller lakes and swamps merged together to become the Hongze Lake, which is one of the famous Five Lakes in China.

This major event was also connected to the formation of many other lakes along the Huai River basins, including the Luoma Lake, Gaoyou Lake and Shaobo Lake.

But still, few fluvial lakes can be classified as large lakes. Moreover, they are mostly residing in the plain regions only. To create even more sizeable lakes and over all terrains of the vast country, something more extraordinary is necessary.

We need the formidable power of tectonic activities.

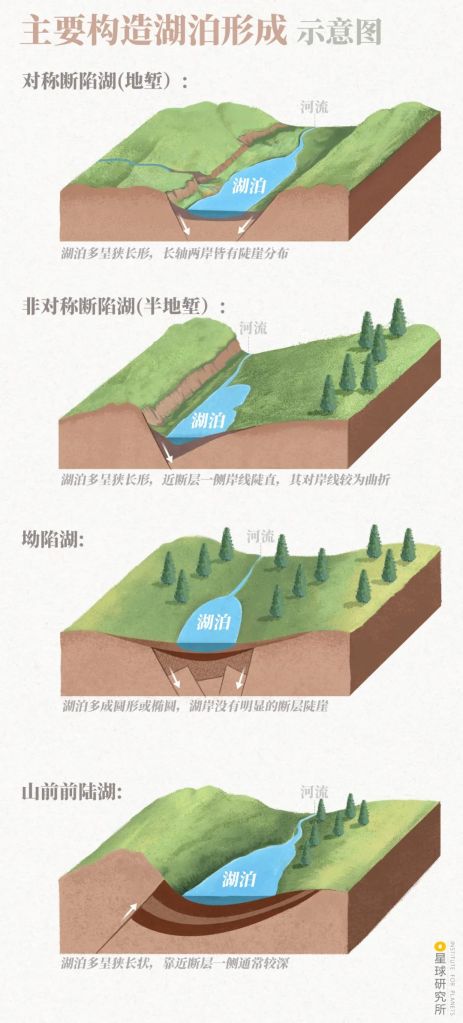

8. Tectonic activities 构造的力量

China has a complex tectonic architecture.

Crustal folding and faulting are frequent events in this country due to constant and vigorous tectonic plate movements. Mountains are created during these events, and so are structural basins when the flat floors exhibit downward motion in relation to the surrounding margins.

Infused with rainfall, river inflow, meltwater and underground water, a water body gradually builds up in basins with a closed or partially-closed structure. This is how tectonic lakes are formed.

Symmetric rift lakes (对称断陷湖) are usually long and narrow, lined by steep cliffs on either bank

Asymmetric rift lakes (非对称断陷湖) are also mostly long and narrow, with a straight embankment neighbouring the fault

Depression lakes (拗陷湖) are commonly round or oval in shape, without apparent faults or cliffs by the banks

Foreland lakes (山前前陆湖) normally have a long shape with a greater depth near the fault

(diagram: 赵榜, Institute for Planets)

These tectonic lakes are not only scattered all across the land of China, they are absolutely dominating the large and medium-sized lake categories.

8.1 Extra-large lakes in China

Of all the 10 extra-large lakes in China, 8 are tectonic lakes.

Tectonic lakes (构造湖): Qinghai Lake (青海湖), Poyang Lake (鄱阳湖), Dongting Lake (洞庭湖), Hulun Lake (呼伦湖), Siling Tso (色林错), Namu Tso (纳木错), Bosten Lake (博斯腾湖), and Xingkai Lake or Lake Khanka (兴凯湖)

Non-tectonic lakes (非构造湖): Hongze Lake (洪泽湖) and Tai Lake (太湖)

Pink shade: exorheic regions (外流区); yellow shade: endorheic regions (内流区)

(diagram: 陈思琦, Institute for Planets)

They are, respectively, the Qinghai Lake, the largest of all lakes in China with a surface area of 4254.90 square kilometres.

The Poyang Lake, which was famously cited by the eminent poet Wang Bo in one of his most distinguished work Tribute to King Teng’s Tower.

落霞与孤鹜齐飞,秋水共长天一色

A solitary wild duck flies alongside the multicoloured sunset clouds, and the autumn water is merged with the boundless sky into one hue.

《滕王阁序》王勃 Tribute to King Teng’s Tower by Wang Bo

English translation by Luo Jingguo

(photo: 廖昊)

The Dongting Lake, made famous by the sincere poem A Dedication to Premier Zhang while Beholding the Dongting Lake by Meng Haoran.

气蒸云梦泽,波撼岳阳城

As the warm mist blankets the Yunmeng Lake, rocking waves keep charging at the Yueyang Tower.

《望洞庭湖赠张丞相》孟浩然 A Dedication to Premier Zhang while Beholding the Dongting Lake by Meng Haoran

(photo: 叶长春)

The Hulun Lake on the great plains of Hulunbuir Prairie.

The Siling Tso located on the Tibetan Plateau with an area of 2129.09 square kilometres.

The Namu Tso, with an area of 2040.90 square kilometres.

And the Bosten Lake, the largest lake in Xinjiang and the tenth largest in China.

Although the Xingkai Lake, spanning the border between China and Russia, has a surface area of 4350 square kilometres in total, the area within China’s border is only 1057 square kilometres, therefore it is ranked only ninth in China.

8.2 Large lakes in China

Tectonic lakes account for 15 out of 17 large lakes in China.

While most large lakes are within the borders of China, the Pangong Tso and Buir Lake are on the borders between China and India, and Mongolia, respectively. The area of Chinese portion of the latter is only 38.4 square kilometres

Tectonic lakes (构造湖): Zhari Namco (扎日南木错), Tangra Yumco (当惹雍错), Yamdrok Yumco (羊卓雍错), Pangong Tso (班公错), Ang Laren Tso (昂拉仁错), Har Lake (哈拉湖), Wulanwula Lake (乌兰乌拉湖), Mirik Guangdram Tso (赤布张错), Ngoring Lake (鄂陵湖), Gyaring Lake (扎陵湖), Ebi Lake (艾比湖), Ulungar Lake (乌伦古湖), Ayakum Lake (阿雅克库木湖), Chao Lake (巢湖), Buir Lake (贝尔湖)

Non-tectonic lakes (非构造湖): Nansi Lake (南四湖) and Gaoyou Lake (高邮湖)

Pink shade: exorheic regions (外流区); yellow shade: endorheic regions (内流区)

(diagram: 陈思琦, Institute for Planets)

Respectively, they are the Zhari Namco, Tangra Yumco, Yamdrok Yumco, Pangong Tso and Ang Laren Tso in Tibet.

The Har Lake, Wulanwula Lake, Mirik Gyangdram Tso, Ngoring Lake and Gyaring Lake in Qinghai.

Together with Gyaring Lake, they are the only two large open freshwater lakes on the Tibetan Plateau

(photo: 王生晖)

The Ebi Lake, Ulungar Lake and Ayakum Lake in Xinjiang.

The Chao Lake (literally ‘bird’s nest lake’).

And the Buir Lake on the China-Mongolian border.

8.3 Regional ‘spokeslakes’

Many medium and small-sized tectonic lakes have become a landmark, or the ‘spokeslake’, for various regions.

These include Yunnan’s largest lake, Dianchi Lake.

Erhai Lake, the second largest in Yunnan.

And the Fuxian Lake, ranked third in Yunnan.

Of note, the surrounding margins of Fuxian Lake has been rising over the past 12,000 years. As the lake basin experiences continuous faulting, it is now the third deepest lake in China, with an average depth of 89.6 metres, and 155 metres at the deepest.

With an area of 214.53 square kilometres and a volume of 18.9 billion cubic metres, it holds 16 and 7.5 times more water than the Dianchi Lake and Erhai Lake, respectively

(photo: 商睿)

In Sichuan, the best representatives for the less common large lakes in the region are the Lugu Lake.

Two thirds of the lake is in Sichuan, and the remaining in Yunnan

(photo: 阿五在路上)

And the Qiong Lake.

In Xinjiang, the water of the Sayram Lake located in the western ranges of Northern Tianshan Mountain is so clear and azure blue that the lake looks like an encrusted sapphire on the heavenly mountains.

The Zintun in Taiwan, more commonly called Sun Moon Lake, is located between the Yushan Mountain (literally ‘jade mountain’) and the Alishan Range. Although it is only 4.4. square kilometres big, it is the treasure island’s largest pearl.

It is now repurposed into a reservoir and has been enlarged

(photo: 柴江辉

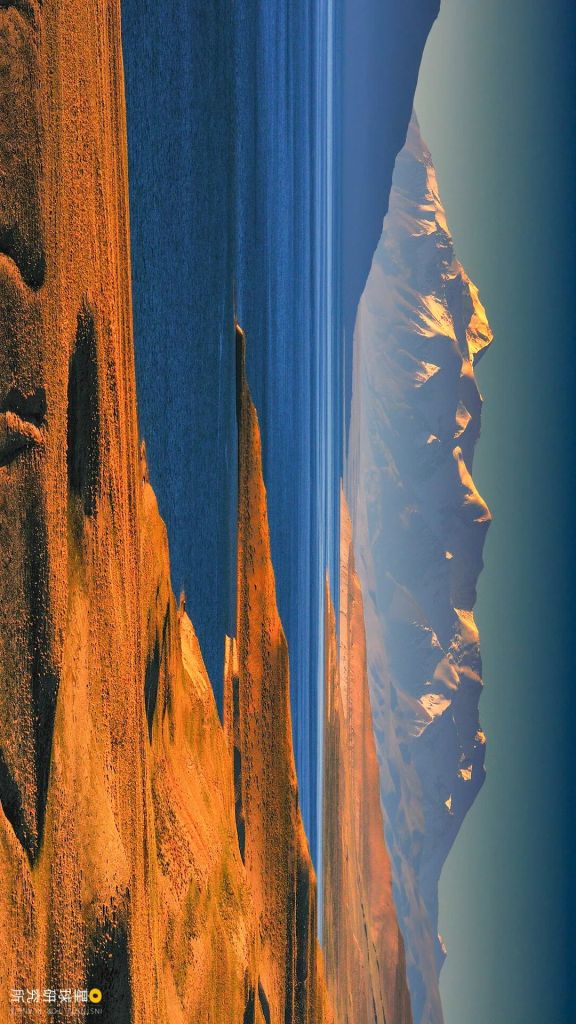

The majority of tectonic lakes, however, are still concentrated on the Tibetan Plateau.

To the north of the Gangdisê Ranges and Nyenchen Tanglha Mountains, the regions between the Namu Tso and Pangong Tso are connected by ‘fault after fault’.

Lakes in the regions north of Gangdisê Ranges, regardless of their sizes, are named as ‘tso (错)’ as opposed to ‘lake’, which is the same word for ‘mistake/fault’ in Chinese, therefore this tectonic lake region is often referred to as ‘fault after fault’

(photo: 孙岩)

Such as the Mapam Yumtso and Langa Tso that stand as a couple in the Ngari Prefecture.

And the stunning Puma Yumco in Shannan.

9. Combination of forces 合力创造

The repertoire of lake types is further enlarged by the natural forces that work together.

While many of the glacial lakes on the Altai and Tianshan Mountains were initially tectonic basins, the prolonged effects of tectonic faulting and glacial wearing have made these lakes much deeper with steep banks.

One such lakes, the Kanas Lake, has an average depth of 120.1 metres. The maximum depth of 188.5 metres makes it the second deepest lake in China.

The mechanisms underlying the formation of Tai Lake is, however, still under debate. In addition to oceanic and fluvial processes as well as tectonic activities, meteorite impact has also been proposed to help create China’s fourth largest lake.

We are also hoping for more conclusive evidence for its formation process

(photo: 韩阳)

10. The fate of China’s lakes 湖泊的命运

And that summarises all the eight magnificent natural forces that are responsible for lake formation, either independently or jointly.

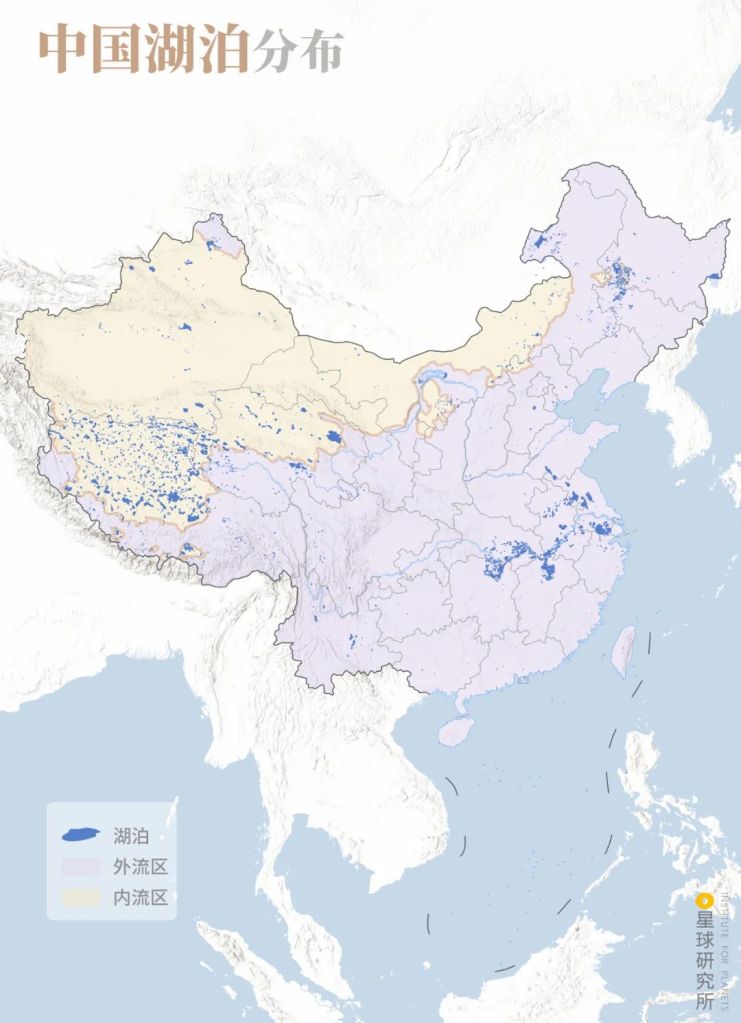

Through the creation of volcanic crater lakes, glacial lakes, aeolian lakes, lagoons, karst lakes, landslide dams, fluvial lakes and tectonic lakes, these forces sprinkled tens of thousands of glittering pearls across the vast land of China.

Blue: lakes; pink shade: exorheic regions; yellow shade: endorheic regions

(diagram: 陈思琦, Institute for Planets)

Creators of these pearls, unfortunately, are usually themselves the destroyer, especially for the smaller lakes.

Volcanic crater lakes will be shattered by the next volcano eruption.

Glacial lakes will either be swallowed by advancing glaciers or crushed by sudden glacial movements.

Aeolian lakes will be buried by moving dunes and end up as groundwater.

Lagoons will become new land surface through persistent sand deposition driven by waves and tidal activities.

Karst lakes will dry up as the sinkhole and cracks get bigger.

Landslide dams, which are inherently unstable, will not last forever.

Most lakes will tranquilly tread through their predestined life cycle.

But this path certainly diverges for open and closed lakes.

Closed lakes become increasingly saline over time with accumulating mineral salt.

Starting as freshwater lakes.

(photo: 山风)

They gradually turn into brackish lakes, and then saline lakes.

(photo: 蒋晨明)

Slowly, they become salt lakes, and finally dry salt lakes.

A lifetime of changes.

And in the exorheic regions, open lakes undergo constant shrinkage as sand continues to deposit in the lake bed. They too slowly transform into wetlands and ultimately dry land.

Nevertheless, for both open and closed lakes, their life cycles are not necessarily progressive nor unidirectional. Any changes in the basin structure, climate and even river-lake relationship can impact on the surface area, volume and water quality of the lakes.

Owing to increase in rainfall and meltwater on the Tibetan Plateau, the surface area of Siling Tso increased from 1132.76 square kilometres in 1976 to 2349.46 square kilometres in 2010, replacing the Namu Tso as the largest lake in Tibet

(photo: 马春林)

But with the exception of the Tibetan Plateau, China’s lakes are more affected by human activities than any other factors, especially in modern times.

Lake reclamation for agriculture in the eastern regions greatly reduced the number of lakes and the area of existing ones. Erosion caused by human activities also accelerated sediment movement and deposition in lakes.

The annual sediment entry into Dongting Lake is 123.85 million cubic metres; the lake is experience the worst deposition in China

(photo: 余明)

Many lakes are either shrinking or disappearing because of this, including the five major freshwater lakes, namely Poyang Lake, Dongting Lake, Tai Lake, Hongze Lake and Chao Lake.

The situation of Dongting Lake is the most worrying.

Over the 100 years between the late 19th and late 20th centuries, the lake shrunk almost by half, from 5000 square kilometres to 2700 square kilometres. The once largest freshwater lake in China is now ranked second.

Luckily, lakes are not disappearing in large numbers anymore recently, thanks to the regulatory measures against over-reclamation introduced over the past 30 years.

Instead, the most pressing issue now is lake pollution and eutrophication caused by disposal of industrial and agricultural waste water as well as household sewage.

And for the arid lands in northwest regions, shrinkage and drying of downstream lakes are usually caused by the construction of dams in the upstream.

While the lakes on the Tibetan Plateau are not influenced by human activity as much as those in other regions, they are very sensitive to climate changes.

Global warming leads to increase in rainfall and meltwater. As a result, lakes in Tibet experienced massive expansion over the last 40 years.

(diagram: 郑伯容, Institute for Planets)

But expanding too quickly can also lead to a series of undesirable events.

Between August and September 2011, the Zhuonai Lake in Hoh Xil bursted due to continuous heavy rainfall. The flood extended across several closed lakes and merged with the exorheic Yangtze River basin, which severely damaged the surrounding ecosystem as well as the construction facilities of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway and Highway.

We now know better than ever that lakes are both beautiful and fragile.

While respecting their natural course of life, we should always be vigilant about the potential impact of global warming and human activities on these lovely lakes.

Never should we allow the beauty today to become our regret tomorrow.

Production team:

Text: 风子

Photos: 余宽

Maps: 陈思琦

Design: 赵榜, 郑伯容

Review: 云舞空城, 陈景逸

References:

[1]中国科学院南京地理与湖泊研究所编,中国湖泊调查报告[M]. 北京:科学出版社, 2019.06.

[2]王苏民,窦鸿身主编. 中国湖泊志[M]. 北京:科学出版社, 1998.09.

[3]施成熙主编. 中国湖泊概论[M]. 北京:科学出版社, 1989.03.

[4]王洪道等编著. 我国的湖泊[M]. 北京:商务印书馆, 1984.03.

[5]孙伟富等. 1979-2010年我国大陆海岸潟湖变迁的多时相遥感分析[J]. 海洋学报,2015,37(03):54-69.

[6]张祖陆等. 南四湖的形成及水环境演变[J]. 海洋与湖沼,2002(03):314-321.

[7]邓贵平.九寨沟世界自然遗产地旅游地学景观成因与保护研究[D].成都理工大学,2011.

[8]苏岑. 洞庭湖演化变迁的遥感监测数学模型[J]. 国土资源遥感, 2016, v.28;No.108(01):184-188.

[9]闫立娟等. 近40年来青藏高原湖泊变迁及其对气候变化的响应[J]. 地学前缘,2016,23(04):310-323.

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光