Feature photo: 黄昆震

Original piece:《桥桥桥桥桥桥桥桥桥》

Produced by Institute for Planets (星球研究所)

Written by 桢公子

Translated by Kelvin Kwok

Posted with permission from Institute for Planets

Dedicated to all Chinese bridge builders

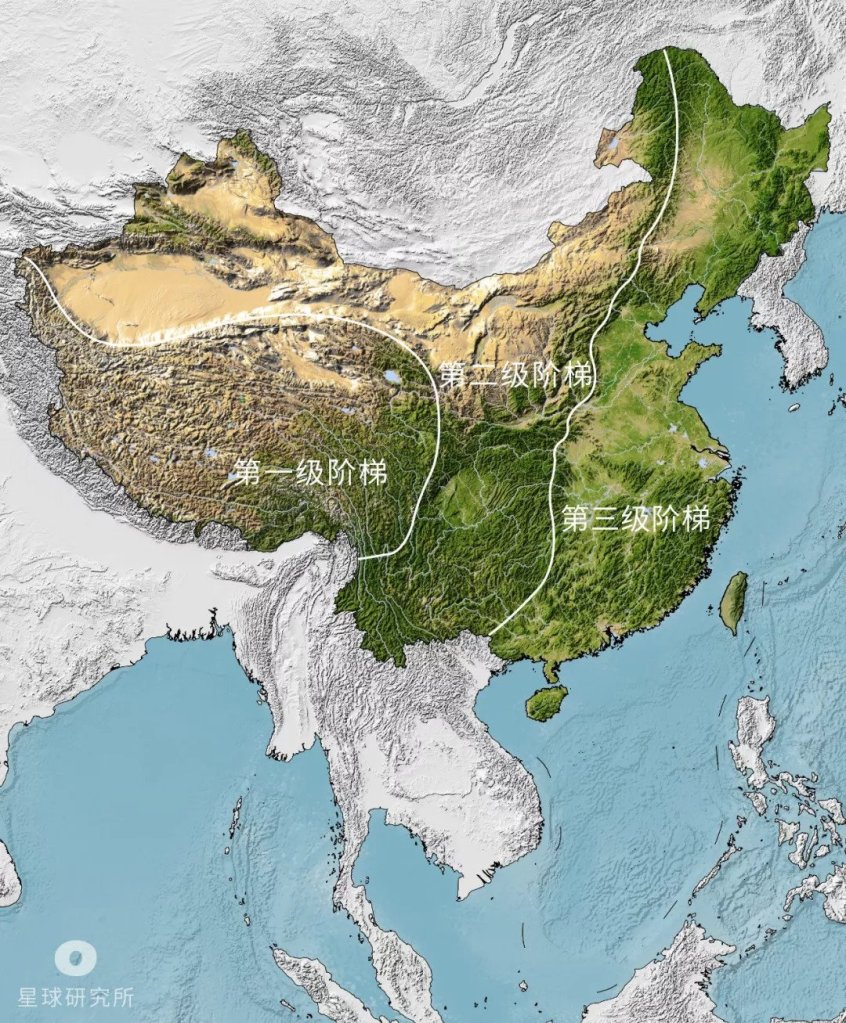

The distinctive altitude profile across the land of China is immediately visible on a topographic map of the country.

From the towering plateau and mountains in the west to vast plains and rolling hills in the east, the terrains of China have been referred to as the ‘three-step ladder’.

From left to right: first, second and third step of the ladder topography

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Originating from the Tibetan plateau, rivers progress down the terrain ladder, cutting through mountains and forming precipitous cliffs and narrow gorges along the way.

Creating wide canyons through persistent weathering.

Marching across the plains and separating the land with wide channels in the lower course.

From left to right: Puyang River, Fuchun River and Qiantang River

(photo: 潘劲草, best served with landscape view)

And finally meeting the sea, where they greet large bays and scattered archipelagos.

While these landscapes sculpted by rivers may look gorgeous to us, they are formidable natural barriers to transportation and communication. For the local people trapped inside, there is no way out.

How can humans, tiny as they are, overcome all this?

1. Crossing on a beam 架梁为桥

When our ancestors laid down the first log of wood to cross, a bridge was created. With just a long beam resting on two piers at both ends, a beam bridge is the simplest and most classic type of bridge ever built.

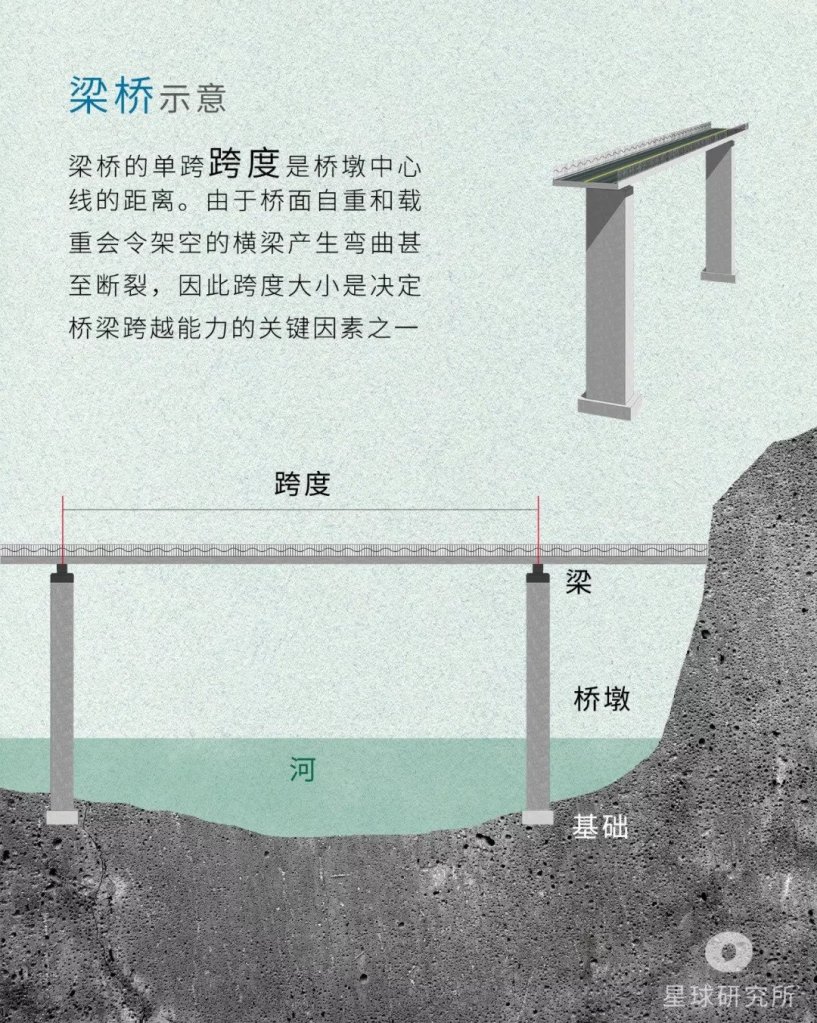

The span (跨度) of a beam bridge is the distance between the centre of the two piers (桥墩). Since the self-weight of the overhead beam (梁) and the load on it may cause bending and even fracture, its span is one of the major limiting factors for the spanning ability of the bridge

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

In ancient times, beam bridges were especially popular in Guangdong and Fujian, partly because of the high abundance of hard granite in these regions, which was the best construction materials for bridges.

Fixation of the pedestals with farmed oysters was a breakthrough

(photo: 雾雨川)

As modern steelmaking technologies matured in the 19th century, the bridge engineering community welcomed a whole new era.

In 1874, America built the world’s first steel bridge. But it was not for another 10 or so years before China completed her first modern steel bridge.

For China in those times, steel bridges were so advanced and expensive that she could only afford one for railway constructions, not to mention the heavy reliance on Western countries for design, construction and capital.

Only until 1937 could China independently design and build her first road-rail bridge, the Qiantang River Bridge in Hangzhou.

Unfortunately, the Japanese army captured Shanghai just three months later.

In order to stop the enemies from crossing the river, the chief designer of the bridge, Mr Mao Yisheng, had to blow up the bridge with his own hands. It took 16 years before the bridge was reconstructed.

The longest single span of this bridge is approximately 66 metres. This is approaching the span limit for a single-supported beam bridge like this one, where one beam rests on every two neighbouring piers.

To have a longer single span, continuous beam bridges are needed.

The beam in a continuous beam bridge extends across multiple piers without any hinges or joints. Since the local bending is restrained by adjacent parts, the beam is more resistant to fractures.

When encountering the same load with a given span, the bending in a continuous beam is less than that in a single-supported beam

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

The oldest beam bridges across the Yangtze River, including the Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge, Baishatuo Yangtze River Railway Bridge and the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, are all continuous beam bridges. It is noteworthy that the Nanjing Yangtze River Bridge, which has a maximum single span reaching 160 metres, was domestically designed and built.

As the Chinese saying goes, ‘a flyover bridging the north and south reduces natural moats to walking paths (一桥飞架南北,天堑变通途)’.

(photo: 艾小龙)

In addition to breakthroughs in steel bridges, a new technology was also gaining popularity across China.

It has a simple but smart design, where prestressed reinforcement steel bars (rebars) are embedded in the bridge beam made of concrete. Like a stretched spring, rebars tend to contract. This property is utilised to confer added resistance to bending of the concrete beam, which allows a longer span.

This is known as the prestressed concrete.

When encountering the same load, a prestressed concrete beam experiences less downward bending than a conventional reinforced concrete (普通钢筋混凝土), avoiding cracks forming from below

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Compared to steel, prestressed concrete was much cheaper, and was therefore more frequently used. Since its introduction, numerous highway bridges had sprung up all over the country, each making memorable appearances on the arena of Chinese bridge engineering.

This photo shows the Baoji-to-Tianshui section of the Lianyungang-Khorgas Expressway

(photo: 石耀臣)

Today, beam bridges are still widely used. There are even established production lines for standardised components, which can be produced in mass scale for on-site assembly.

While there is length limit on a single span, having multiple spans allows a bridge to elongate into an enormous meandering dragon that is capable of traversing vast rivers.

The bridge on the far side is the Changjiangyuan Grand Bridge of the Qinghai-Tibet Railway, consisting of 42 spans of 32 metres each; the bridge closer by is the Tuotuo River Bridge

(photo: 姜曦)

Leaping across huge bays.

(photo: 添小天)

And even replacing the road with a new path in the air.

(photo: 陈益科)

2. A beam in disguise 似梁非梁

Always remember, never judge a bridge by its appearance.

Due to its modest look, a type of bridge is often mistaken as beam bridges. But in fact, it exhibits completely different mechanical characteristics which require much more complex designs and calculations.

It is called the rigid frame bridge.

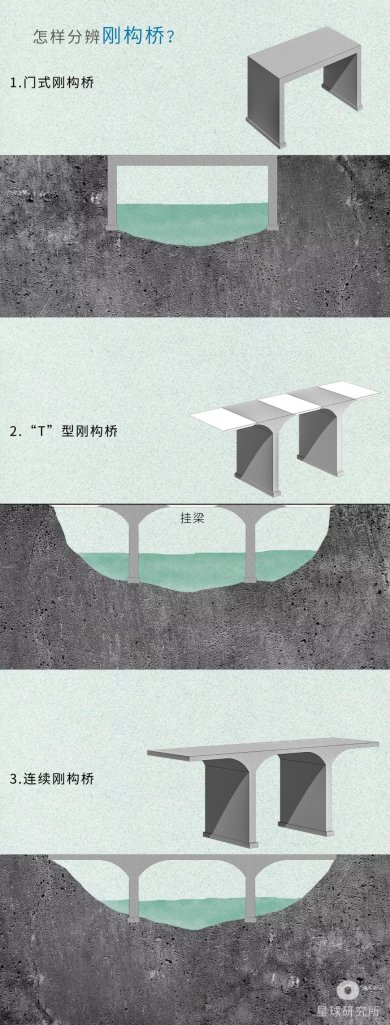

What are the different types of rigid frame bridge?

1. Portal frame bridge (门式)

2. T-shaped rigid frame bridge (T型)

3. Consecutive rigid frame bridge (连续)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Combined into one, the piers and the beam can now share the burden in resisting any bending in the beam structure.

When encountering the same load with a given span, the bending in portal frame bridge is less than that in simple-supported beam bridge

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

This greatly strengthens the beam structure, allowing it to have a longer span, or a thinner deck.

The tallest pier of the bridge has a height of 182.5 metres. It held the title of ‘Asia’s tallest pier’ prior to the completion of the Hezhang Bridge in Guizhou

(photo: 姜曦)

Consecutive rigid frame bridges, in particular, quickly became the favourite choice across the country since its introduction in the 1990s. This can be attributed to their superiority in both the bridge span and commuting experience for drivers.

(photo: 李琦)

There is but one issue with these bridges.

They are extremely sensitive to temperature, which causes substantial expansion and contraction. A pair of stubborn piers may lead to bending and deformation of the beam.

But smart engineers always know how to get around.

They designed even taller piers, making the bridge more flexible still.

Tall piers are more flexible than their short counterparts, and thus more readily release stress that builds up with temperature changes

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Tall piers are the perfect match for mountainous regions, where lofty bridge decks rise along the ranges, supported by majestic piers that insert deep into the floors of the valleys.

A heavenly ride on the highways.

A continuous stretch of rigid frame bridges squeezes through mountains and valleys, merging with the Sidu River Bridge further ahead

(photo: 文林)

Nevertheless, there is no one-size-fits-all design when it comes to bridges.

Sky-scraping piers have no purpose for rivers flowing through the plains. To lower the heights of bridge decks while maintaining pier flexibility, the shortened piers will have to be ‘slimmed down’.

The main span is supported by thin and flattened piers

(photo: 倪前辉)

Alternatively, new forms of piers can be adopted.

(photo: 姚朝辉)

Building an economical rigid frame bridge means striking a balance among thin piers, stable beams and low cost for construction.

This is no simple task. There are only a handful of its kind that span more than 300 metres.

One of them is the second bridge of the Multi-lane Shibanpo Yangtze River Bridge in Chongqing. Completed in 2006, its main span reached 330 metres, providing ample space for ship navigation along the Yangtze River.

The Shibanpo Yantze River Bridge is crowned the longest consecutive rigid frame bridge in the world.

(photo: 鬼迹, best served with landscape view)

Standing right next to it is the Chongqing Yangtze River Bridge, the first highway bridge to ever cross the Yangtze River.

Running in close parallel, the bridges of two different eras tranquilly paint the 40 years of vicissitudes.

3. Taming the tide with rainbow 长虹卧波

It would be too early to think the Chinese people have already conquered their homeland with these bridges.

When faced with steep cliffs and coursing rivers, or the busy traffic under the bridge, vertical piers are no longer viable. A new type of bridge that can cross the distance in a single stride is needed.

The arch bridges.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

Arch bridges have been a household name among Chinese.

Every primary school student in China has read about the Zhaozhou Bridge in textbooks.

A bridge that was built more than 1400 years ago.

One that has endured multiple floods and earthquakes and yet still standing today with perfectly intact structure.

It truly is the role model for bridge engineering.

(photo: 石耀臣)

Arch bridges are not simply a historical landmark in old towns and ancient gardens, but more so a classic imagery in Chinese poetry.

长桥卧波,未云何龙;复道行空,不霁何虹。

杜牧《阿房宫赋》Rhapsody on the Efang Palace by Du Mu, Tang Dynasty

How can there be a hovering dragon in a cloudless sky? It is but a crouching bridge atop the tide.

How can there be an arching rainbow on a rainless day? It is but a dangling corridor between pavilions.

Today, more than half of all the highway bridges in China are arch bridges.

These include the most traditional stone arch bridges.

In an arch bridge, the bearing at each end not only supports the deck, but also provides a lateral thrust. This strongly protects the arch from deforming and increases the spanning capacity.

1. Deck arch bridge (上承式拱桥)

Supported by columns (立柱), it has a relatively large space under the bridge

Arrows indicate direction of forces

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

The main arch (主拱) is supported by columns and hangers (吊杆)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Also supported by columns and hangers, it is more suitable for regions with stringent requirement on deck height

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

While giving arch bridges the edge over other bridge types, the unique arch structure introduces unique problems not faced by others. Without hard rocks and strong foundation soil, the arch bearings struggle to provide a steady support for the bridges.

To overcome this, the whole bridge has to be slimmed down to stabilise the bearings.

The Heng-style arch pioneered by Chinese engineers utilises thin and light concrete backbone that raises the maximum span to 330 metres.

(photo: 李贵云)

Alternatively, one can install a tie rod at the intersections of the main arch and the deck. The thrust that develops at the bearings can then be balanced by the tension in the hangers and the tie.

This is known as the tied-arch bridge.

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

A tied-arch bridge is needed as the banks of the Han River have relatively soft foundation soil

(photo: 潘锐之)

Arch bridges made from ordinary concrete were gradually replaced by a new variation that can have an even larger span.

This time, steel tubes are included in the formula.

When filled with concrete, these steel tubes act as a protective coat that strengthens the concrete. They also conveniently become the skeleton frame for construction of the bridge and greatly reduce the building time.

Killing many birds with one stone, the steel tube concrete arch bridge was for a while the obvious choice.

The Qingchuan Bridge shown above is also a steel tube concrete arch bridge

(photo: 梁炳全)

But engineers did not stop there.

They wrapped the concrete-filled steel tubes with concrete again to further stiffen the arch skeleton. As of today, the maximum span of this so-called stiff-skeleton concrete arch bridge has exceeded 400 metres.

(photo: 王璐)

As China topped the world ranking of steel production in 1993, bridge builders had since become less and less refrained from steel usage. This led to rise of the steel arch bridges, creating engineering wonders across the country.

The six railways running through the bridge are connected to Beijing-Shanghai High-speed Railway, Shanghai-Wuhan-Chengdu Passenger Railway and Nanjing Metro

(photo: 艾小龙)

And decorating cities with their elegant forms.

(photo: 张扬的小强)

With current technology, a single-span arch bridge is able to span 552 metres. When erected, it will be taller than the 109-storey CITIC Tower in Beijing, also popularly known as the China Zun.

This Heng-style steel arch bridge is the longest arch bridge in the world

(photo: 鬼迹)

And what comes on stage next will lead us beyond the 1000-metre span capacity.

4. Musical strings of steel 钢铁琴弦

Three decades ago, all Shanghai had was a flat skyline.

In the downtown, the long banks of Huangpu River are almost 400 metres apart. The ferry was the only means to cross and commute. A bridge across the river was urgently needed. Unfortunately, the Chinese back then lacked the experience to build such a long-span bridge.

Impossible it might seem, Li Guohao and Xiang Haifan, the then president and professor respectively at the Tongji University, insisted on a domestically built ‘Huangpu River’s first bridge‘.

Xiang wrote in his letter to the then Mayor of Shanghai,

上海是我国的东大门,黄浦江大桥应成为上海市的标志传名于世。建造黄浦江大桥不但是1000万上海人民的宿愿,也是上海桥梁工程界的梦想,在学校我们也一直以此激励桥梁专业的学生们。

Shanghai is China’s eastern gateway to the world, and the Huangpu River Bridge should be known globally as the landmark of Shanghai city. Building the Huangpu River Bridge is not only the wish of the 10 million Shanghainese, but also the dream of all bridge engineers in Shanghai.

This has always been the greatest aspiration for students majoring in bridge engineering.

The Nanpu Bridge was eventually completed in 1991, with merely half the expected costs estimated in the original proposal.

Its opening marked the first milestone of domestically built long-span bridges in China.

(photo: 一乙)

A 50-storey tower stands magnificently at each end of the Nanpu Bridge. Attaching the main deck to the two bridge towers, the 180 steel cables were arranged in a way that may be recognised as strings on a harp

This is known as the cable-stayed bridge.

Just two years after the completion of Nanpu Bridge, the same team of engineers built the Yangpu Bridge. With a span of over 600 metres, it was once the longest cable-stayed bridge in the world.

Together with Nanpu Bridge, the sister bridges are honoured as the ‘matchless pair’.

But for cable-stayed bridges like the Yangpu Bridge, such a span was nothing more than trying a hand.

In a cable-stayed bridge, each steel cable attached to the deck is pulled upwards and anchored at the tower. This upward tension collectively serves as invisible piers along the deck, which prevent deck bending and greatly increase the spanning capacity of the bridge.

Green arrows indicate forces acting on the deck

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Complemented by major breakthroughs in construction materials and engineering calculations, cable-stayed bridges accomplished the 1000-metre span within a mere 50 years since their invention.

Initially expected to be the first cable-stayed bridge exceeding the 1000-metre span, it was later overtaken by Sutong Yangtze River Bridge

(photo: 图虫创意)

But a large span comes with enormous self-weight. The crossing traffic and vigorous crosswind also add to the load on the cables that gets transferred to the anchoring towers.

Therefore, extra strong and stable bridge towers are indispensable for cable-stayed bridges.

Green arrows indicate forces acting on the tower

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

Equally critical is the configuration of the bridge towers.

Either as a ‘lone warrior guarding the pass (一夫当关)’.

(photo: 邓国晖)

Or as a couple.

(photo: 刘雅彬)

Or even in tandem.

(photo: 陶进)

The aesthetic temperament of contemporary cable-stayed bridges is wholly reflected in their unchallenged beauty. They are the pinnacle of the fusion between engineering and art.

(photo: 何小清)

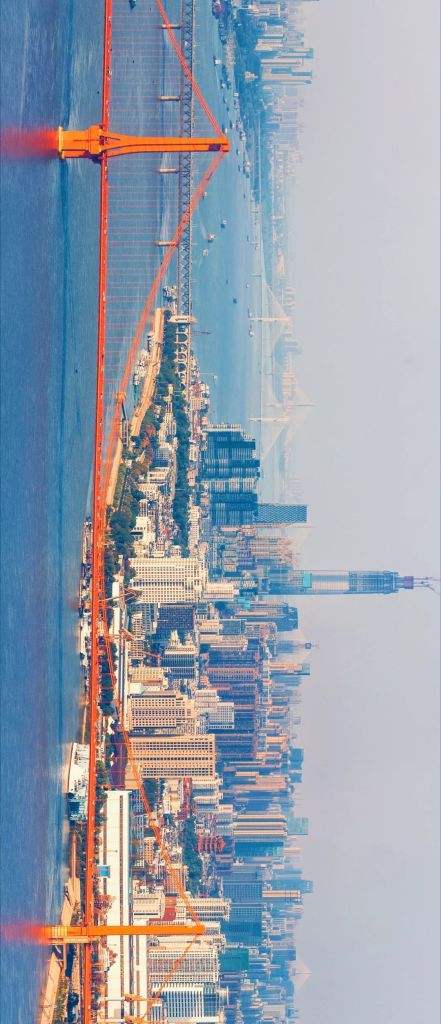

More importantly, the inherent symmetrical nature of cable-stayed bridges makes ‘self-anchoring’ more achievable. This is a valuable feature for bridges in terrains without natural anchoring grounds, particularly the bay areas.

This photo shows the two cable-stayed bridges as part of the Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge

(photo: 黄昆震)

However, every design has its downsides.

While the cables support the main deck primarily with upward pulling force, their tilted angles inevitably introduce axial forces parallel to the deck. As the span increases, so does the number of cables. Eventually, the accumulating axial force will overwhelm the deck and crush it.

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

What make things worse are the cables themselves.

Attached cables become more and more tilted with increasing deck length. The sagging of the cables due to enormous self-weight also hampers the stable support of the deck.

Considering additional factors such as crosswind and costs, the limits of cable-stayed bridges gradually become apparent.

No wonder they say, ‘cables can make you or break you‘.

With a main span of 1088 metres, it is to date the longest cable-stayed bridge in China

(photo: VCG)

To achieve a 2000-metre span, we can only bet on the next performer on stage.

5. Champion of all bridges 跨度王者

The terrains in Southwest China are undulating and densely populated with steep mountains and turbulent waters. Before the age of modern bridges, commute was based on the simplest and crudest methods.

For some, that means to cross a raging river with zip wires.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

Or perhaps with a rope bridge in a more ‘advanced’ region.

(photo: 小强先森)

Never would the inventors and users of these humble crossings have imagined that the same type of bridge can span up to 1650 metres today, making it the champion of all bridges.

With a main span of 1650 metres, it is the longest bridge in China

(photo: 邬涛)

This is the modern suspension bridge.

Its load-bearing system consists of lofty towers, long and curved main cables and rigid anchors, all of which give rise to its characteristic appearance.

Main components of the bridge include gravity/tunnel anchorage (重力/隧道式锚碇), bridge towers (桥塔), main cables (主缆) and suspension cables (吊索)

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

What distinguishes between a modern suspension bridge and an age-old rope bridge is that the former is comprised of a pair of extremely strong and durable main cables.

Take Baling River Bridge in Guizhou as an example, the basic component of the main cable is a high-strength steel wire with a diameter of 5.25 millimetres. 91 of such wires are compacted into a wire rope, and a total of 208 wire ropes are bundled together to make up the main cable.

When anchored, two of these main cables running in parallel are capable of bearing up to 10 thousand tons of steel beam.

Compared to the massive beams, the load of traffic is almost negligible and no longer causes any substantial deck oscillation.

The wobbly nature of ancient rope bridges is now history.

Nevertheless, to eliminate any potential risk of deck bending as the traffic load increases, engineers can always install a stiffener beam right below the deck.

(diagram: 张靖, Institute for Planets)

While cable-stayed bridges and suspension bridges are both ‘cable’ bridges, the suspension cables in suspension bridges are attached vertically to the deck. Hence, the deck will not experience any compression by axial force from the cables regardless of the span.

According to scientists’ estimations, suspension bridges can theoretically achieve a staggering span of more than 5000 metres.

(photo: 柴峻峰)

This is how suspension bridges have conquered countless natural barriers that were previously impossible to overcome.

From vast rivers.

(photo: 田春雨)

To mountains and gorges.

With a deck height of 560 metres, it was the world’s highest bridge before the completion of the First Beipan River Bridge (Duge/Nizhu River Bridge) in Yunan

(photo: 远方的阿伦)

And across the straits.

It is the main passage connecting the airport and the city

(photo: Kenny)

Looking back on the history of Chinese bridges, we were once ahead of the world, and were once far behind everyone. It has been a bumpy ride with lots of twists and turns, yet scientists and engineers never stopped marching ahead.

Though confronted with many difficulties, they managed to solve all sorts of problems ranging from structural components to geography and geology, and deal with many unpredictable conditions. Even during the dirt-poor era in the last century, Chinese bridge builders were able to keep innovating and accomplishing.

(photo: 黄猛)

Thanks to them, there are more than 800,000 highway bridges standing in China today. The total mileage of high-speed railway bridges has even exceeded 10,000 kilometres.

Crossing mountains and rivers, connecting cities and counties, these bridges together turn the whole country into a wondrous ‘bridge museum’ with a gallery space of 9.6 million square kilometres.

(photo: 陶进, best served with landscape view)

References:

- 《桥梁漫笔》万明坤等

- 《中国桥梁史纲》项海帆等

- 《中国桥梁概念设计》项海帆等

- 《桥梁史话》茅以升

… The End …

星球研究所

一群国家地理控,专注于探索极致风光